Chapter 5

Linear Models

"Truth is ever to be found in simplicity, and not in the multiplicity and confusion of things." — Isaac Newton

Chapter 5 of MLVR delves into the theory, implementation, and practical application of linear models for both regression and classification tasks. The chapter begins with an introduction to linear models, followed by a detailed exploration of the mathematical foundations of linear regression. It then extends to regularized linear regression models, highlighting their importance in preventing overfitting. The chapter also covers logistic regression, including its extensions to multinomial and ordinal cases, and concludes with a discussion on evaluation metrics for linear models. By integrating theoretical insights with practical Rust implementations, this chapter equips readers with the tools to apply linear models effectively to a wide range of machine learning problems.

5.1. Introduction to Linear Models

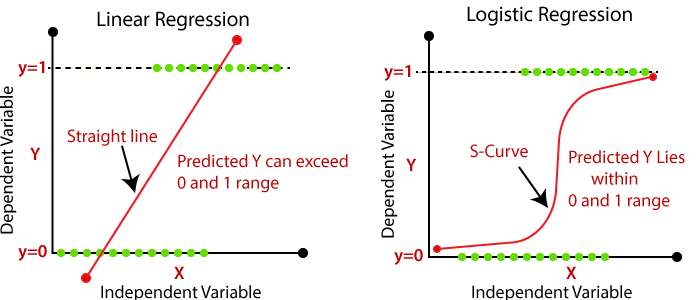

Linear models form the foundation of many machine learning techniques, and their simplicity and effectiveness make them crucial in both academic and practical settings. Linear models are widely used in statistics and machine learning for modeling the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. Two of the most common linear models are linear regression and logistic regression.

Linear regression is perhaps the most straightforward and widely used method for predicting a continuous outcome. It models the relationship between the input features and the target variable by fitting a linear equation to the observed data. The primary goal is to find the best-fitting line (or hyperplane in higher dimensions) that minimizes the sum of squared differences between the observed and predicted values.

Logistic regression, on the other hand, is used for binary classification problems where the outcome is a categorical variable. Instead of predicting a continuous value, logistic regression estimates the probability that a given input belongs to a particular class. This is achieved by applying the logistic function to a linear combination of input features, ensuring that the output lies between 0 and 1, which can then be interpreted as a probability.

Figure 1: Illustration of Linear Models for Regression.

As foundational to the field of machine learning, linear models serve as the simplest yet powerful tools for modeling relationships between variables. They are integral in both understanding the fundamental concepts of learning algorithms and in practical applications where interpretability and computational efficiency are paramount. This section delves into the formal mathematical definitions of linear regression and logistic regression, explores their geometric interpretations, discusses the underlying assumptions, and illustrates their implementation in Rust using the ndarray and linfa libraries.

The assumptions behind linear models are fundamental to understanding their application. Linear models assume a linear relationship between the input features and the target variable. This means that the change in the target variable is proportional to the change in any of the input features. Additionally, linear regression assumes that the residuals (the differences between observed and predicted values) are normally distributed and have constant variance (homoscedasticity). Violations of these assumptions can lead to misleading results, so it is essential to validate them before relying on the model’s predictions.

Linearity is a core concept in these models. In linear regression, linearity means that the model predicts the target variable as a weighted sum of the input features. The weights (or coefficients) determine the contribution of each feature to the prediction. In logistic regression, linearity refers to the linear combination of input features before applying the logistic function. Understanding this concept helps in selecting and engineering features that can improve model performance.

At the core of the principle of linearity assumes a linear relationship between the input variables and the output variable. Formally, for a dataset consisting of $n$ observations, each observation $i$ includes an input vector $\mathbf{x}_i \in \mathbb{R}^d$ and a corresponding output $y_i$. A linear model predicts the output $\hat{y}_i$ as a linear function of the input features:

$$ \hat{y}_i = f(\mathbf{x}_i) = \mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}_i + b, $$

where $\mathbf{w} \in \mathbb{R}^d$ is the weight vector, and $b \in \mathbb{R}$ is the bias term. The objective is to find the optimal $\mathbf{w}$ and $b$ that best approximate the relationship between inputs and outputs.

The importance of linear models in machine learning stems from their interpretability and simplicity. They often serve as a starting point for modeling complex systems and provide insights into the significance of different features. Applications span various domains, including economics for forecasting, biology for gene expression analysis, and social sciences for understanding behavioral patterns.

Linear regression aims to model the conditional expectation of the output variable $y$ given the input variables $\mathbf{x}$, assuming a linear relationship. The model is expressed as:

$$ y_i = \mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}_i + b + \epsilon_i, $$

where $\epsilon_i$ is the error term capturing the deviation of the observed value from the predicted value. The goal is to estimate $\mathbf{w}$ and $b$ by minimizing the sum of squared errors (SSE):

$$SSE = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( y_i - \mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}_i - b \right)^2.$$

This optimization problem can be solved analytically by setting the gradient of the SSE with respect to $\mathbf{w}$ and $b$ to zero, leading to the normal equations:

$$ \begin{cases} \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X} \mathbf{w} + \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{1} b = \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}, \\ \mathbf{1}^\top \mathbf{X} \mathbf{w} + n b = \mathbf{1}^\top \mathbf{y}, \end{cases} $$

where $\mathbf{X}$ is the design matrix of inputs, $\mathbf{y}$ is the vector of outputs, and $\mathbf{1}$ is a vector of ones. Solving these equations yields the least squares estimates for $\mathbf{w}$ and $b$.

Logistic regression is utilized for binary classification problems, where the output variable $y$ takes on values in $\{0, 1\}$. Instead of modeling $y$ directly, logistic regression models the probability that $y = 1$ given $\mathbf{x}$ :

$$ P(y_i = 1 | \mathbf{x}_i) = \sigma(\mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}_i + b), $$

where $\sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-z}}$ is the sigmoid function. The likelihood function for the observed data is:

$$ L(\mathbf{w}, b) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} P(y_i | \mathbf{x}_i) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \sigma(\mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}_i + b)^{y_i} [1 - \sigma(\mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}_i + b)]^{1 - y_i}. $$

Maximizing the likelihood is equivalent to minimizing the negative log-likelihood (cross-entropy loss):

$$\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{w}, b) = -\sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[ y_i \log \sigma(\mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}_i + b) + (1 - y_i) \log (1 - \sigma(\mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x}_i + b)) \right].$$

This optimization problem is convex and can be solved using iterative methods such as gradient descent or Newton-Raphson.

Geometrically, linear regression seeks to find the hyperplane in the ddd-dimensional feature space that minimizes the perpendicular distances (errors) to the data points. This hyperplane represents the best linear approximation of the data. In logistic regression, the hyperplane serves as a decision boundary that separates the feature space into regions corresponding to different classes. The distance of a point from the hyperplane, transformed by the sigmoid function, gives the probability of class membership.

Understanding the assumptions behind linear models is crucial for their proper application. The primary assumptions include linearity of the relationship between inputs and outputs, independence of the errors ϵi\\epsilon_iϵi, homoscedasticity (constant variance of errors), and normality of errors for inference purposes. Violation of these assumptions may lead to biased estimates or misleading inferences.

The concept of linearity implies that the effect of each input variable on the output is additive and proportional to its coefficient. This simplification facilitates interpretation but may not capture complex nonlinear relationships inherent in real-world data. Techniques such as polynomial regression or interaction terms can extend linear models to capture some nonlinearities.

Linear models play a pivotal role in predicting outcomes based on input features by estimating the weights that quantify the contribution of each feature. In practice, they provide a balance between model complexity and interpretability, often yielding satisfactory performance with lower risk of overfitting compared to more complex models.

Implementing linear regression and logistic regression in Rust leverages the language's performance and safety features. The ndarray library provides N-dimensional array support akin to NumPy in Python, facilitating efficient numerical computations. The linfa library is a comprehensive toolkit for machine learning in Rust, offering various algorithms, including linear and logistic regression.

The

ndarraycrate is essential for handling multi-dimensional arrays and matrices in Rust, providing efficient storage and computational capabilities. It supports various operations such as slicing, arithmetic, linear algebra routines, and more. This library is analogous to NumPy in Python, offering a familiar interface for those transitioning from Python to Rust.The

linfacrate is a comprehensive machine learning library that provides a range of algorithms for tasks such as regression, classification, clustering, and dimensionality reduction. It is designed with a focus on flexibility and performance, leveraging Rust's features to ensure safe and efficient code. Thelinfa-linearandlinfa-logisticsub-crates specifically implement linear and logistic regression algorithms, respectively.

First, we need to add the necessary dependencies to our Cargo.toml file:

[dependencies]

linfa = "0.7.0"

linfa-linear = "0.7.0"

linfa-logistic = "0.7.0"

ndarray = "0.15.0"

Next, let’s write the code for implementing a linear regression model:

use linfa::prelude::*;

use linfa_linear::LinearRegression;

use ndarray::array;

fn main() {

// Input features (X) and target variable (y)

let x = array![[1.0, 2.0], [2.0, 3.0], [3.0, 4.0], [4.0, 5.0]];

let y = array![3.0, 5.0, 7.0, 9.0];

// Create a dataset

let dataset = Dataset::new(x, y);

// Fit the linear regression model

let model = LinearRegression::default().fit(&dataset).unwrap();

// Predict new values

let new_x = array![[5.0, 6.0]];

let prediction = model.predict(&new_x);

// Extract value from ArrayBase and print it

let prediction_value = prediction[0]; // Get the first value from the prediction result

println!("Prediction: {}", prediction_value);

}

This example demonstrates how to implement a linear regression model in Rust. We start by defining our input features and target variables as ndarray arrays. These arrays are then used to create a Dataset, which serves as the input to our linear regression model. The LinearRegression struct from the linfa-linear crate is then used to fit the model to the data. Finally, we make predictions on new data points by passing them to the predict method.

For logistic regression, the implementation is quite similar, but instead of predicting continuous values, we predict probabilities:

use linfa::prelude::*;

use linfa_logistic::LogisticRegression;

use ndarray::array;

use ndarray::Array2;

fn main() {

// Input features (X) and binary target variable (y)

let x: Array2<f64> = array![[1.0, 2.0], [2.0, 3.0], [3.0, 4.0], [4.0, 5.0]];

let y = array![0, 0, 1, 1];

// Create a dataset

let dataset = Dataset::new(x, y);

// Fit the logistic regression model

let model = LogisticRegression::default().fit(&dataset).unwrap();

// Predict class labels for new values

let new_x = array![[5.0, 6.0]];

let prediction = model.predict(&new_x);

println!("Prediction: {:?}", prediction);

}

In this example, we follow a similar process as with linear regression, but we use the LogisticRegression struct from the linfa-logistic crate. The predict_proba method is used to obtain the predicted probabilities, which can then be thresholded to obtain binary predictions.

Both examples showcase the power and flexibility of Rust in implementing linear models. The ndarray crate provides efficient handling of arrays and matrices, while the linfa ecosystem offers a range of machine learning algorithms that can be easily integrated into Rust projects. By leveraging these tools, you can build robust and performant machine learning models in Rust, making it an excellent choice for both educational purposes and real-world applications.

The applications of linear models are vast, ranging from simple predictive modeling to more complex tasks such as feature selection and model interpretation. Whether you are building a recommendation system, forecasting sales, or analyzing clinical data, linear models can serve as a valuable tool in your machine learning toolbox. With Rust’s growing ecosystem and its focus on performance and safety, you can implement these models in a way that is both efficient and reliable, ensuring that your machine learning projects are built on a solid foundation.

One practical application of linear regression is in predicting housing prices based on features such as square footage, number of bedrooms, and location. By modeling the relationship between these features and the price, one can estimate the value of a property given its characteristics. The interpretability of linear models allows real estate professionals to understand how each feature contributes to the price.

Logistic regression finds extensive use in medical diagnosis, such as predicting the presence or absence of a disease based on patient data like blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and age. The probability outputs of logistic regression provide clinicians with a quantitative measure of risk, aiding in decision-making processes.

Linear models, encompassing linear and logistic regression, are fundamental tools in machine learning that combine mathematical rigor with practical applicability. They offer a balance between simplicity and effectiveness, making them suitable for a wide range of problems where interpretability and computational efficiency are important. Understanding the mathematical foundations, geometric interpretations, and underlying assumptions of these models is crucial for their effective application. Implementing these models in Rust, with the support of libraries like ndarray and linfa, allows for the development of high-performance machine learning applications that can leverage Rust's safety and concurrency features. By applying linear models to real-world problems, practitioners can gain valuable insights and make informed predictions based on data.

5.2. Mathematical Foundation of Linear Regression

Linear regression is a fundamental statistical method used in machine learning and data analysis to model the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. It serves as a cornerstone for understanding more complex algorithms and provides insights into the underlying structure of data. This section delves into the mathematical foundations of linear regression, exploring the least squares method, deriving the linear regression equation, understanding the normal equations, and examining the concepts of bias, variance, and overfitting. We will also interpret the significance of the coefficient estimates and implement linear regression from scratch in Rust using matrix operations provided by the nalgebra library, applying it to a real-world dataset.

The primary goal of linear regression is to find the best-fitting linear relationship between the independent variables (features) and the dependent variable (target). This relationship is modeled using a linear equation whose parameters are estimated from the data.

The least squares method is a standard approach in regression analysis to approximate the solution of overdetermined systems (more equations than unknowns). It minimizes the sum of the squares of the residuals—the differences between the observed values and the values predicted by the model.

Consider a dataset with nnn observations. Each observation iii consists of a dependent variable $y_i$ and a vector of independent variables $\mathbf{x}_i = [x_{i1}, x_{i2}, \dots, x_{ip}]^\top$. The linear regression model assumes that the dependent variable is a linear combination of the independent variables plus an error term:

$$ y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i1} + \beta_2 x_{i2} + \dots + \beta_p x_{ip} + \epsilon_i, $$

where $\beta_0$ is the intercept, $\beta_j$ for $j = 1, \dots, p$ are the coefficients, and $\epsilon_i$ is the error term.

The least squares method seeks to find the coefficient estimates $\hat{\beta}_0, \hat{\beta}_1, \dots, \hat{\beta}_p$ that minimize the residual sum of squares (RSS):

$$ RSS = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( y_i - \beta_0 - \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j x_{ij} \right)^2. $$

To derive the estimates of the coefficients, we set up the minimization problem:

$$ \min_{\beta_0, \beta_1, \dots, \beta_p} RSS. $$

This involves taking partial derivatives of $RSS$ with respect to each$\beta_j$ and setting them to zero:

$$ \frac{\partial RSS}{\partial \beta_j} = -2 \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_{ij} \left( y_i - \beta_0 - \sum_{k=1}^{p} \beta_k x_{ik} \right) = 0, \quad \text{for } j = 0, 1, \dots, p. $$

These equations are known as the normal equations and form a system of $p+1$ equations with $p+1$ unknowns.

To solve the normal equations efficiently, we express them in matrix form. Let $\mathbf{y}$ be the vector of dependent variables, and $\mathbf{X}$ be the design matrix, defined as:

$$ \mathbf{X} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & x_{11} & x_{12} & \dots & x_{1p} \\ 1 & x_{21} & x_{22} & \dots & x_{2p} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 1 & x_{n1} & x_{n2} & \dots & x_{np} \\ \end{bmatrix}, $$

where the first column is a column of ones corresponding to the intercept term.

The regression model can be written in matrix notation as:

$$ \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} + \boldsymbol{\epsilon}, $$

where $\boldsymbol{\beta} = [\beta_0, \beta_1, \dots, \beta_p]^\top$ and $\boldsymbol{\epsilon}$ is the vector of error terms.

The residual sum of squares becomes:

$$ RSS = (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta})^\top (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}). $$

To find the minimum of $RSS$, we take the derivative with respect to $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ and set it to zero:

$$ \frac{\partial RSS}{\partial \boldsymbol{\beta}} = -2 \mathbf{X}^\top (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}) = \mathbf{0}. $$

Rearranging, we obtain the normal equations in matrix form:

$$ \mathbf{X}^\top\mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}. $$

Assuming that $\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X}$ is invertible (which requires that the columns of $\mathbf{X}$ are linearly independent), we solve for $\boldsymbol{\beta}$:

$$ \boldsymbol{\beta} = (\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}. $$

Understanding the concepts of bias and variance is crucial in the context of model performance and generalization. Bias refers to the error introduced by approximating a real-world problem, which may be complex, by a simplified model. In linear regression, bias arises if the true relationship between the variables is nonlinear, but we model it linearly.

Variance refers to the error introduced by the variability of the model prediction for a given data point due to variations in the training data. High variance in a model implies that it might perform well on the training data but poorly on unseen data.

Overfitting occurs when a model captures not only the underlying pattern in the data but also the noise. This typically happens when the model is too complex relative to the amount of training data, such as including too many features or polynomial terms in linear regression.

Balancing bias and variance is essential for good predictive performance. Techniques like cross-validation, regularization (e.g., ridge regression, lasso), and dimensionality reduction can help mitigate overfitting and achieve a better bias-variance tradeoff.

The estimated coefficients $\hat{\beta}_j$ in a linear regression model quantify the expected change in the dependent variable $y$ for a one-unit change in the independent variable $x_j$, holding all other variables constant. Interpreting these coefficients provides insights into the relationship between variables.

For example, a positive $\hat{\beta}_j$ suggests that as $x_j$ increases, $y$ tends to increase, while a negative $\hat{\beta}_j$ indicates an inverse relationship. The magnitude of $\hat{\beta}_j$ reflects the strength of the association.

Assessing the statistical significance of the coefficients is important to determine whether the observed relationships are likely to be genuine or due to random chance. This involves hypothesis testing, where we test the null hypothesis $H_0: \beta_j = 0$ against the alternative $H_a: \beta_j \neq 0$. The t-statistic for each coefficient is calculated, and p-values are used to assess significance.

Multicollinearity, where independent variables are highly correlated, can affect the stability and interpretability of the coefficient estimates. It inflates the variances of the estimates, making them sensitive to small changes in the model or data.

Implementing linear regression from scratch involves directly coding the mathematical equations derived earlier. In Rust, we can use the nalgebra library, which provides efficient matrix and vector operations necessary for linear algebra computations.

To implement linear regression from scratch, we start with data preparation by collecting or generating a dataset containing independent variables $\mathbf{X}$ and a dependent variable $\mathbf{y}$, where each row in $\mathbf{X}$ represents an observation and each column corresponds to a feature. To include the intercept term (bias) in our linear model, we augment $\mathbf{X}$ by adding a column of ones, which allows the intercept to be seamlessly integrated into the matrix calculations. With the prepared data, we compute the matrices $\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X}$; which is a $(p+1) \times (p+1)$ matrix (where $p$ is the number of features) that encapsulates the relationships among the independent variables by measuring their covariance, and $\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}$ is a $(p+1) \times 1$ vector that captures the covariance between each independent variable and the dependent variable. We then solve the normal equations using the formula $\boldsymbol{\beta} = (\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}$ to find the coefficient estimates $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ that minimize the residual sum of squares; this requires $\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X}$ to be invertible, which holds if the independent variables are linearly independent—however, issues like multicollinearity can render $\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X}$ singular or ill-conditioned, necessitating alternative methods like singular value decomposition (SVD) or regularization techniques such as ridge regression to obtain stable estimates. After obtaining $\boldsymbol{\beta}$, we make predictions on new data $\mathbf{X}_{\text{new}}$ (which also includes a column of ones) by calculating $\hat{\mathbf{y}} = \mathbf{X}_{\text{new}} \boldsymbol{\beta}$, thereby applying the learned linear relationship to estimate the dependent variable based on new independent variables. Finally, we evaluate the model's performance using metrics like the Mean Squared Error (MSE), defined as $\text{MSE} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2$, where $n$ is the number of observations, $y_i$ are the actual values, and $\hat{y}_i$i are the predicted values—a lower MSE indicates better predictive accuracy; additionally, we compute the coefficient of determination $R^2 = 1 - \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \bar{y})^2}$, where $\bar{y}$ is the mean of the actual values, with $R^2$ values closer to 1 indicating a better fit—evaluating these metrics provides insights into the model's effectiveness and helps identify potential issues such as overfitting or underfitting.

By following these steps—data preparation, computing essential matrices, solving the normal equations, making predictions, and evaluating the model—we implement linear regression from scratch. This process not only reinforces the mathematical concepts underpinning linear regression but also provides practical experience in applying these concepts to real-world data using matrix operations. Implementing the model in a programming language like Rust, with libraries such as nalgebra for efficient matrix computations, allows for scalable and high-performance applications of linear regression in various domains.

Let's implement linear regression on a real-world dataset. We will use the California Housing Dataset, which includes information on housing prices along with various features. To prepare the data for linear regression, we start by loading the dataset using Rust's csv crate, reading from a CSV file where each row represents a census block group with features such as median income, average number of rooms, and house age. Once the data is loaded, we handle missing values to maintain data integrity; this involves checking for any absent entries and either imputing them with appropriate statistics like the mean or median values or removing incomplete records altogether. After addressing missing data, we proceed with feature selection and scaling: we select relevant features based on domain knowledge or through correlation analysis to ensure that the most impactful variables are included in the model. Scaling the features is also crucial, especially when employing regularization techniques, as it normalizes the range of the independent variables, typically through standardization or normalization methods, allowing the model to converge more efficiently and ensuring that all features contribute proportionally to the outcome.

// Append Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

csv = "1.3.0"

nalgebra = "0.33.0"

use nalgebra as na;

use csv;

use na::{DMatrix, DVector};

use std::error::Error;

use csv::Reader;

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

// Load data from CSV

let mut rdr = Reader::from_path("california_housing.csv")?;

let mut features = Vec::new();

let mut targets = Vec::new();

for result in rdr.records() {

let record = result?;

// Extract features and target variable from each record

// Assume columns: median_income, total_rooms, housing_median_age, median_house_value

let median_income: f64 = record[0].parse()?;

let total_rooms: f64 = record[1].parse()?;

let housing_median_age: f64 = record[2].parse()?;

let median_house_value: f64 = record[3].parse()?;

features.push(vec![1.0, median_income, total_rooms, housing_median_age]); // Include intercept term

targets.push(median_house_value);

}

// Convert features and targets to nalgebra matrices

let n_samples = features.len();

let n_features = features[0].len();

let x_data: Vec<f64> = features.into_iter().flatten().collect();

let x = DMatrix::from_row_slice(n_samples, n_features, &x_data);

let y = DVector::from_vec(targets);

// Compute X^T * X and X^T * y

let xtx = x.transpose() * &x;

let xty = x.transpose() * y;

// Solve for beta

let beta = xtx.lu().solve(&xty).expect("Failed to compute coefficients");

println!("Estimated coefficients:");

for (i, coef) in beta.iter().enumerate() {

println!("Beta_{}: {}", i, coef);

}

// Evaluate model on training data

let y_pred = x * beta;

let residuals = &y - &y_pred;

let mse = residuals.dot(&residuals) / n_samples as f64;

println!("Mean Squared Error on training data: {}", mse);

Ok(())

}

The estimated coefficients indicate the impact of each feature on the median house value. For example, if the coefficient for median income is positive, it suggests that higher income levels are associated with higher house prices.

It's important to consider the units and scales of the features when interpreting the coefficients. Additionally, checking for multicollinearity is crucial, as highly correlated features can distort the coefficient estimates.

Linear regression provides a powerful yet straightforward method for modeling the relationship between variables. By minimizing the residual sum of squares through the least squares method, we obtain the coefficient estimates that define the best-fitting linear model for the data.

Understanding the derivation of the linear regression equation and the normal equations equips us with the mathematical tools to implement the model from scratch. Exploring concepts like bias, variance, and overfitting highlights the importance of model selection and the need to balance complexity with generalization performance.

Interpreting the coefficient estimates allows us to draw meaningful conclusions about the relationships in the data, which is valuable in many fields such as economics, engineering, and the social sciences.

Implementing linear regression in Rust using matrix operations demonstrates the practical application of these mathematical concepts. By applying the model to a real-world dataset, we gain insights into the challenges of data preprocessing, feature selection, and model evaluation.

Mastering the mathematical foundation of linear regression lays the groundwork for advancing into more complex models and machine learning techniques, fostering a deeper understanding of how to analyze and interpret data effectively.

5.3. Extensions to Linear Regression

Linear regression is a fundamental tool in machine learning for modeling the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. However, in practical applications, especially with high-dimensional data or multicollinearity among predictors, linear regression models can suffer from overfitting. Overfitting occurs when the model captures noise instead of the underlying data pattern, leading to poor generalization on new data. To mitigate overfitting and improve model performance, regularization techniques are employed. This section explores the mathematical foundations of regularization methods—Ridge Regression, Lasso Regression, and Elastic Net—and their impact on the bias-variance trade-off. We will delve into how these techniques adjust model complexity, the role of regularization parameters, and provide practical implementations in Rust, including tuning strategies for optimal performance.

Regularization introduces a penalty term to the loss function used in linear regression, discouraging large coefficients and complex models. This penalty helps to prevent overfitting by smoothing the estimated coefficients, effectively controlling the model complexity.

Consider the standard linear regression model with $n$ observations and $p$ predictors:

$$ y_i = \beta_0 + \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j x_{ij} + \epsilon_i, $$

where $y_i$ is the dependent variable, $x_{ij}$ are the independent variables, $\beta_0$ is the intercept, $\beta_j$ are the coefficients, and $\epsilon_i$ is the error term.

The objective is to find $\boldsymbol{\beta} = [\beta_0, \beta_1, \dots, \beta_p]^\top$ that minimizes the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS):

$$ RSS(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( y_i - \beta_0 - \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j x_{ij} \right)^2. $$

Regularization modifies this optimization problem by adding a penalty term $P(\boldsymbol{\beta})$ multiplied by a regularization parameter $\lambda \geq 0$:

$$\min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \left\{ L(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = RSS(\boldsymbol{\beta}) + \lambda P(\boldsymbol{\beta}) \right\}$$

Ridge Regression introduces an $L_2$ penalty, which is the sum of the squares of the coefficients:

$$P_{\text{ridge}}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j^2.$$

The Ridge Regression optimization problem becomes:

$$ \min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \left\{ L_{\text{ridge}}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( y_i - \beta_0 - \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j x_{ij} \right)^2 + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j^2 \right\}. $$

This penalty shrinks the coefficients towards zero but does not set them exactly to zero, retaining all predictors in the model. The solution to Ridge Regression has a closed-form expression derived from the normal equations.

In matrix notation, let $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$ be the vector of responses, $\mathbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p}$ be the matrix of predictors, and $\boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathbb{R}^p$ be the coefficient vector (excluding the intercept). The Ridge Regression objective function can be written as:

$$ L_{\text{ridge}}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta})^\top (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}) + \lambda \boldsymbol{\beta}^\top \boldsymbol{\beta}. $$

To find the minimizer $\boldsymbol{\hat{\beta}}$, we take the derivative with respect to $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ and set it to zero:

$$ -2 \mathbf{X}^\top (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\hat{\beta}}) + 2 \lambda \boldsymbol{\hat{\beta}} = \mathbf{0}. $$

Rewriting:

$$ (\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X} + \lambda \mathbf{I}) \boldsymbol{\hat{\beta}} = \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}, $$

where $\mathbf{I}$ is the $p \times p$ identity matrix. The solution is:

$$ \boldsymbol{\hat{\beta}} = (\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X} + \lambda \mathbf{I})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}. $$

Lasso Regression introduces an $L_1$ penalty, which is the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients:

$$ P_{\text{lasso}}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \sum_{j=1}^{p} |\beta_j|. $$

The Lasso Regression optimization problem is:

$$ \min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \left\{ L_{\text{lasso}}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( y_i - \beta_0 - \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j x_{ij} \right)^2 + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^{p} |\beta_j| \right\}. $$

Unlike Ridge Regression, Lasso does not have a closed-form solution due to the non-differentiability of the $L_1$ norm at zero. However, it can be solved using optimization techniques like coordinate descent or subgradient methods.

The $L_1$ penalty can shrink some coefficients exactly to zero, effectively performing variable selection. This sparsity property makes Lasso useful for high-dimensional data where feature selection is important.

Elastic Net combines both $L_1$ and $L_2$ penalties:

$$ P_{\text{elastic}}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \alpha \sum_{j=1}^{p} |\beta_j| + \frac{1}{2} (1 - \alpha) \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j^2, $$

where $\alpha \in [0, 1]$ balances the contributions of the $L_1$ and $L_2$ penalties. The Elastic Net optimization problem is:

$$ \min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \left\{ L_{\text{elastic}}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( y_i - \beta_0 - \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j x_{ij} \right)^2 + \lambda \left( \alpha \sum_{j=1}^{p} |\beta_j| + \frac{1}{2} (1 - \alpha) \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j^2 \right) \right\}. $$

Elastic Net addresses limitations of Lasso when predictors are highly correlated by combining the strengths of both Ridge and Lasso.

Regularization adds bias to the model estimates but reduces variance, leading to improved generalization on unseen data. By penalizing large coefficients, regularization discourages complex models that may overfit the training data. This is particularly important when the number of predictors $p$ is large relative to the number of observations nnn, or when predictors are highly correlated.

The bias-variance trade-off is a key concept in statistical learning. High model complexity (low bias) can lead to high variance, making the model sensitive to fluctuations in the training data. Conversely, increasing bias by simplifying the model can reduce variance but may underfit the data.

Regularization techniques increase bias by penalizing coefficient magnitude but reduce variance by preventing the model from fitting noise in the data. The regularization parameter $\lambda$ controls this trade-off.

Regularization effectively controls model complexity:

Ridge Regression shrinks coefficients towards zero but retains all predictors, resulting in a model that is less sensitive to multicollinearity.

Lasso Regression can set some coefficients to zero, performing variable selection and producing a sparser model.

Elastic Net provides a compromise, allowing for both coefficient shrinkage and variable selection, particularly useful when predictors are correlated.

By adjusting $\lambda$ and $\alpha$, one can fine-tune the model complexity to achieve better generalization. Here is how regularization parameters can affect the linear model:

Regularization Parameter $\lambda$: A larger $\lambda$ increases the penalty on coefficient magnitude, leading to smaller coefficients and a simpler model. A smaller $\lambda$ reduces the penalty, allowing the model to fit the training data more closely.

Mixing Parameter $\alpha$ in Elastic Net: Controls the balance between $L_1$ and $L_2$ penalties. Setting $\alpha = 1$ results in Lasso, while $\alpha = 0$ yields Ridge Regression. Intermediate values blend the two penalties.

Selecting optimal values for these parameters is crucial and typically involves cross-validation to assess model performance on validation data.

Rust, with its performance and safety features, is well-suited for implementing machine learning algorithms. Libraries like smartcore provide the necessary tools for numerical computations and data manipulation.

The smartcore ecosystem provides Ridge Regression implementation.

Example: Ridge Regression in Rust

use smartcore::linalg::basic::matrix::DenseMatrix;

use smartcore::linear::ridge_regression::*;

use smartcore::metrics::mean_squared_error;

fn main() {

// Smaller Longley dataset

let x = DenseMatrix::from_2d_array(&[

&[234.289, 235.6, 159.0],

&[259.426, 232.5, 145.6],

&[284.599, 335.1, 165.0],

&[328.975, 209.9, 309.9],

]);

let y: Vec<f64> = vec![83.0, 88.5, 89.5, 96.2];

// Set regularization parameter lambda

let lambda = 0.1;

// Fit Ridge Regression model

let y_hat = RidgeRegression::fit(&x, &y, RidgeRegressionParameters::default().with_alpha(lambda))

.and_then(|ridge| ridge.predict(&x))

.unwrap();

// Evaluate model performance (mean squared error)

let mse = mean_squared_error(&y, &y_hat.to_vec());

println!("Mean Squared Error: {}", mse);

}

As of now, linfa may not have built-in implementations for Lasso and Elastic Net. However, we can use the smartcore crate, which provides these models.

Example: Lasso Regression with SmartCore

use smartcore::linalg::basic::matrix::DenseMatrix;

use smartcore::linear::lasso::*;

use smartcore::metrics::mean_squared_error;

fn main() {

// Smaller Longley dataset

let x = DenseMatrix::from_2d_array(&[

&[234.289, 235.6, 159.0],

&[259.426, 232.5, 145.6],

&[284.599, 335.1, 165.0],

&[328.975, 209.9, 309.9],

]);

let y: Vec<f64> = vec![83.0, 88.5, 89.5, 96.2];

// Set regularization parameter lambda

let lambda = 0.1;

// Fit Lasso Regression model

let y_hat = Lasso::fit(&x, &y, LassoParameters::default().with_alpha(lambda))

.and_then(|ridge| ridge.predict(&x))

.unwrap();

// Evaluate model performance (mean squared error)

let mse = mean_squared_error(&y, &y_hat.to_vec());

println!("Mean Squared Error: {}", mse);

}

Example: Elastic Net with SmartCore

use smartcore::linalg::basic::matrix::DenseMatrix;

use smartcore::linear::elastic_net::*;

use smartcore::metrics::mean_squared_error;

fn main() {

// Smaller Longley dataset

let x = DenseMatrix::from_2d_array(&[

&[234.289, 235.6, 159.0],

&[259.426, 232.5, 145.6],

&[284.599, 335.1, 165.0],

&[328.975, 209.9, 309.9],

]);

let y: Vec<f64> = vec![83.0, 88.5, 89.5, 96.2];

// Set regularization parameter lambda

let lambda = 0.1;

// Fit Elastic Net model

let y_hat = ElasticNet::fit(&x, &y, ElasticNetParameters::default().with_alpha(lambda))

.and_then(|ridge| ridge.predict(&x))

.unwrap();

// Evaluate model performance (mean squared error)

let mse = mean_squared_error(&y, &y_hat.to_vec());

println!("Mean Squared Error: {}", mse);

}

To compare the performance of these regularization techniques, we can apply them to datasets with different characteristics.

Dataset A: High multicollinearity among predictors.

Dataset B: High-dimensional data.

Dataset C: Sparse data where only a few predictors are relevant.

By evaluating metrics like Mean Squared Error (MSE), R-squared, and examining the coefficients, we can assess how each method handles different data scenarios.

Example: Simulation and Comparison

use smartcore::linalg::basic::matrix::DenseMatrix;

use smartcore::linear::ridge_regression::*;

use smartcore::linear::lasso::*;

use smartcore::linear::elastic_net::*;

use smartcore::metrics::mean_squared_error;

fn main() {

// Dataset A: High multicollinearity (variability added)

let x_a = DenseMatrix::from_2d_array(&[

&[1.0, 2.0, 1.0],

&[1.0, 2.1, 0.0],

&[0.0, 1.9, 1.0],

&[1.0, 2.2, 1.0],

]);

let y_a: Vec<f64> = vec![1.0, 1.1, 1.0, 1.2];

// Dataset B: High-dimensional data

let x_b = DenseMatrix::from_2d_array(&[

&[234.289, 235.6, 159.0, 107.608, 1947., 60.323],

&[259.426, 232.5, 145.6, 108.632, 1948., 61.122],

&[258.054, 368.2, 161.6, 109.773, 1949., 60.171],

&[284.599, 335.1, 165.0, 110.929, 1950., 61.187],

&[328.975, 209.9, 309.9, 112.075, 1951., 63.221],

&[346.999, 193.2, 359.4, 113.270, 1952., 63.639],

&[365.385, 187.0, 354.7, 115.094, 1953., 64.989],

&[363.112, 357.8, 335.0, 116.219, 1954., 63.761],

&[397.469, 290.4, 304.8, 117.388, 1955., 66.019],

&[419.180, 282.2, 285.7, 118.734, 1956., 67.857],

&[442.769, 293.6, 279.8, 120.445, 1957., 68.169],

&[444.546, 468.1, 263.7, 121.950, 1958., 66.513],

&[482.704, 381.3, 255.2, 123.366, 1959., 68.655],

&[502.601, 393.1, 251.4, 125.368, 1960., 69.564],

&[518.173, 480.6, 257.2, 127.852, 1961., 69.331],

&[554.894, 400.7, 282.7, 130.081, 1962., 70.551],

]);

let y_b: Vec<f64> = vec![83.0, 88.5, 88.2, 89.5, 96.2, 98.1, 99.0,

100.0, 101.2, 104.6, 108.4, 110.8, 112.6, 114.2, 115.7, 116.9];

// Dataset C: Sparse data (variability added)

let x_c = DenseMatrix::from_2d_array(&[

&[0.0, 0.0, 1.0],

&[1.0, 0.0, 0.0],

&[0.0, 1.0, 0.0],

&[0.0, 0.1, 1.0],

]);

let y_c: Vec<f64> = vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0];

// Set regularization parameter lambda

let lambda = 0.1;

// Function to fit models and print MSE

fn fit_and_evaluate(x: &DenseMatrix<f64>, y: &Vec<f64>, lambda: f64, dataset_name: &str) {

// Ridge Regression

let y_hat_ridge = RidgeRegression::fit(x, y, RidgeRegressionParameters::default().with_alpha(lambda))

.and_then(|ridge| ridge.predict(x))

.unwrap();

let mse_ridge = mean_squared_error(y, &y_hat_ridge.to_vec());

println!("{} - Ridge MSE: {}", dataset_name, mse_ridge);

// Lasso Regression

let y_hat_lasso = Lasso::fit(x, y, LassoParameters::default().with_alpha(lambda))

.and_then(|lasso| lasso.predict(x))

.unwrap();

let mse_lasso = mean_squared_error(y, &y_hat_lasso.to_vec());

println!("{} - Lasso MSE: {}", dataset_name, mse_lasso);

// Elastic Net

let y_hat_elastic = ElasticNet::fit(x, y, ElasticNetParameters::default().with_alpha(lambda))

.and_then(|elastic| elastic.predict(x))

.unwrap();

let mse_elastic = mean_squared_error(y, &y_hat_elastic.to_vec());

println!("{} - Elastic Net MSE: {}", dataset_name, mse_elastic);

}

// Evaluate models on each dataset

fit_and_evaluate(&x_a, &y_a, lambda, "Dataset A (High Multicollinearity)");

fit_and_evaluate(&x_b, &y_b, lambda, "Dataset B (High-Dimensional)");

fit_and_evaluate(&x_c, &y_c, lambda, "Dataset C (Sparse Data)");

}

Observations:

Ridge Regression may retain all variables with small coefficients.

Lasso Regression may set some coefficients to zero, performing variable selection.

Elastic Net may balance the two, selecting groups of correlated variables.

Selecting optimal regularization parameters is critical for model performance.

We can perform k-fold cross-validation to select the best $\lambda$ and $\alpha$ parameters.

use smartcore::linalg::basic::matrix::DenseMatrix;

use smartcore::linear::ridge_regression::*;

use smartcore::linear::lasso::*;

use smartcore::linear::elastic_net::*;

use smartcore::metrics::mean_squared_error;

fn main() {

// Sample datasets (replace with your actual data)

let x_train = DenseMatrix::from_2d_array(&[

&[234.289, 235.6, 159.0],

&[259.426, 232.5, 145.6],

&[284.599, 335.1, 165.0],

&[328.975, 209.9, 309.9],

&[346.999, 193.2, 359.4],

&[365.385, 187.0, 354.7],

]);

let y_train: Vec<f64> = vec![83.0, 88.5, 89.5, 96.2, 98.1, 99.0];

let x_val = DenseMatrix::from_2d_array(&[

&[234.289, 235.6, 159.0],

&[259.426, 232.5, 145.6],

]);

let y_val: Vec<f64> = vec![83.0, 88.5];

let lambdas = vec![0.01, 0.1, 1.0];

let alphas = vec![0.0, 0.5, 1.0]; // For Elastic Net

// Loop through lambda values for Ridge and Lasso

for lambda in lambdas.iter() {

// For Ridge Regression

let ridge_model = RidgeRegression::fit(&x_train, &y_train, RidgeRegressionParameters::default().with_alpha(*lambda)).unwrap();

let y_pred_ridge = ridge_model.predict(&x_val).unwrap();

let mse_ridge = mean_squared_error(&y_val, &y_pred_ridge);

println!("Ridge MSE (lambda = {}): {}", lambda, mse_ridge);

// For Lasso Regression

let lasso_model = Lasso::fit(&x_train, &y_train, LassoParameters::default().with_alpha(*lambda)).unwrap();

let y_pred_lasso = lasso_model.predict(&x_val).unwrap();

let mse_lasso = mean_squared_error(&y_val, &y_pred_lasso);

println!("Lasso MSE (lambda = {}): {}", lambda, mse_lasso);

}

// Now loop through alpha values for Elastic Net

for alpha in alphas.iter() {

for lambda in lambdas.iter() {

// For Elastic Net

let enet_params = ElasticNetParameters::default().with_alpha(*lambda).with_l1_ratio(*alpha);

let enet_model = ElasticNet::fit(&x_train, &y_train, enet_params).unwrap();

let y_pred_enet = enet_model.predict(&x_val).unwrap();

let mse_enet = mean_squared_error(&y_val, &y_pred_enet);

println!("Elastic Net MSE (alpha = {}, lambda = {}): {}", alpha, lambda, mse_enet);

}

}

// Select model with lowest MSE

}

Implementing cross-validation requires splitting the data into training and validation sets multiple times and averaging the performance metrics.

Example: K-fold Cross-Validation

use ndarray::stack;

use rand::seq::SliceRandom;

use rand::thread_rng;

fn k_fold_cross_validation(x: &Array2<f64>, y: &Array1<f64>, k: usize, model_type: &str, lambda: f64, alpha: f64) -> f64 {

let n_samples = x.nrows();

let indices: Vec<usize> = (0..n_samples).collect();

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let mut shuffled_indices = indices.clone();

shuffled_indices.shuffle(&mut rng);

let fold_size = n_samples / k;

let mut mse_total = 0.0;

for fold in 0..k {

let start = fold * fold_size;

let end = start + fold_size;

let test_indices = &shuffled_indices[start..end];

let train_indices: Vec<usize> = shuffled_indices.iter().cloned().filter(|i| !test_indices.contains(i)).collect();

let x_train = x.select(Axis(0), &train_indices);

let y_train = y.select(Axis(0), &train_indices);

let x_test = x.select(Axis(0), test_indices);

let y_test = y.select(Axis(0), test_indices);

// Fit model based on model_type

let y_pred = match model_type {

"ridge" => {

let model = RidgeRegression::params().with_alpha(lambda).fit(&x_train, &y_train).unwrap();

model.predict(&x_test)

},

"lasso" => {

let model = Lasso::fit(&x_train, &y_train, LassoParameters::default().with_alpha(lambda)).unwrap();

model.predict(&x_test).unwrap()

},

"elastic_net" => {

let enet_params = ElasticNetParameters::default().with_alpha(lambda).with_l1_ratio(alpha);

let model = ElasticNet::fit(&x_train, &y_train, enet_params).unwrap();

model.predict(&x_test).unwrap()

},

_ => panic!("Invalid model type"),

};

let mse = (&y_test - &y_pred).mapv(|e| e.powi(2)).mean().unwrap();

mse_total += mse;

}

mse_total / k as f64

}

Regularization techniques—Ridge Regression, Lasso Regression, and Elastic Net—are essential tools for improving the generalization performance of linear models, particularly in high-dimensional settings or when predictors are highly correlated. They address overfitting by penalizing large coefficients, effectively controlling model complexity.

Understanding the mathematical foundations of these methods allows us to appreciate their impact on the bias-variance trade-off and the importance of selecting appropriate regularization parameters. Implementing these models in Rust, leveraging libraries like linfa and smartcore, enables efficient computation and practical application to real-world datasets.

By comparing the models on different datasets and employing cross-validation for hyperparameter tuning, we can select the most suitable regularization technique for a given problem, achieving optimal predictive performance.

5.5. Multinomial and Ordinal Logistic Regression

Logistic regression is a fundamental statistical method used for binary classification problems, where the outcome variable can take one of two possible values. However, many real-world problems involve more than two classes or ordered outcomes. Multinomial and ordinal logistic regression are extensions of binary logistic regression that handle multiclass and ordinal outcomes, respectively. This section delves into the mathematical foundations of these models, explores how logistic regression is adapted for multiclass problems, introduces the softmax function, and discusses the interpretation of coefficients in multinomial logistic regression. Additionally, we will implement multinomial and ordinal logistic regression in Rust, apply them to datasets with more than two classes, and evaluate their performance using appropriate metrics.

The extension of logistic regression to handle multiclass outcomes involves generalizing the binary logistic model to predict probabilities across multiple classes. In binary logistic regression, we model the log-odds of the probability of one class over the other. For multiclass problems, we need a model that can estimate the probabilities of each class while ensuring that the probabilities sum to one.

Multinomial logistic regression, also known as softmax regression, is used when the outcome variable can take one of $K$ discrete values (classes), with $K > 2$. The fundamental idea is to model the probability that an observation $\mathbf{x}$ belongs to class $k$ using a generalized linear model.

For each class $k \in \{1, 2, \dots, K\}$, we define a linear function:

$$ z_k = \mathbf{w}_k^\top \mathbf{x} + b_k, $$

where $\mathbf{w}_k$ is the weight vector and $b_k$ is the bias term for class $k$. To convert these linear functions into probabilities, we use the softmax function:

$$ P(y = k | \mathbf{x}) = \frac{e^{z_k}}{\sum_{j=1}^{K} e^{z_j}}. $$

The softmax function ensures that the probabilities are non-negative and sum to one across all classes.

Ordinal logistic regression is used when the outcome variable is ordinal—that is, the classes have a natural order, but the differences between adjacent classes are not necessarily equal. The most common approach is the proportional odds model, which extends the binary logistic regression by modeling the cumulative probabilities.

For each class $k$, we define the cumulative probability:

$$ P(y \leq k | \mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\theta_k - \mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x})}}, $$

where $\theta_k$ are threshold parameters that partition the real line into intervals corresponding to the ordered categories. The coefficients $\mathbf{w}$ are shared across all thresholds, capturing the effect of predictors on the log-odds of being in a higher category.

In binary logistic regression, the log-odds of the positive class are modeled as a linear function of the predictors. Extending this to multiple classes requires a way to compare the probabilities across all classes. Multinomial logistic regression achieves this by modeling the log-odds of each class relative to a reference class or by using the softmax function to directly compute the probabilities.

The softmax function is a generalization of the logistic function to multiple dimensions. It transforms a vector of real-valued scores $\mathbf{z} = [z_1, z_2, \dots, z_K]^\top$ into probabilities that sum to one:

$$ P(y = k | \mathbf{x}) = \frac{e^{z_k}}{\sum_{j=1}^{K} e^{z_j}}. $$

The exponential function ensures that all probabilities are positive, and dividing by the sum normalizes them. The softmax function is crucial in neural networks for classification tasks and in multinomial logistic regression.

In multinomial logistic regression, each class $k$ has its own set of coefficients $\mathbf{w}_k$. The coefficients represent the effect of predictors on the log-odds of belonging to class $k$ relative to the baseline. Interpretation involves comparing the coefficients across classes.

For example, $w_{kj}$ indicates how a one-unit increase in predictor $x_j$ changes the log-odds of being in class $k$ relative to the baseline class, holding all other predictors constant. Positive coefficients increase the likelihood of class $k$, while negative coefficients decrease it.

In practice, it's common to set one class as the reference class (often the last class), and the coefficients for that class are set to zero.

Implementing multinomial logistic regression involves estimating the parameters $\{\mathbf{w}_k, b_k\}_{k=1}^{K}$ that maximize the likelihood of the observed data. Since there is no closed-form solution, optimization algorithms like gradient descent or more advanced methods like Newton-Raphson are used.

We will use the ndarray crate for numerical computations and implement the gradient descent algorithm.

Given a dataset $\{ (\mathbf{x}_i, y_i) \}_{i=1}^{n}$, where $y_i \in \{1, 2, \dots, K\}$, the likelihood $L$ of the observed data is:

$$ L(\{\mathbf{w}_k, b_k\}) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} \prod_{k=1}^{K} P(y_i = k | \mathbf{x}_i)^{\delta_{y_i, k}}, $$

where $\delta_{y_i, k}$ is the Kronecker delta, equal to 1 if $y_i = k$ and 0 otherwise.

The negative log-likelihood (loss function) is:

$$ J(\{\mathbf{w}_k, b_k\}) = -\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{k=1}^{K} \delta_{y_i, k} \log P(y_i = k | \mathbf{x}_i). $$

The gradients with respect to $\mathbf{w}_k$ and $b_k$ are:

$$ \frac{\partial J}{\partial \mathbf{w}_k} = -\sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( \delta_{y_i, k} - P(y_i = k | \mathbf{x}_i) \right) \mathbf{x}_i, $$

$$ \frac{\partial J}{\partial b_k} = -\sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( \delta_{y_i, k} - P(y_i = k | \mathbf{x}_i) \right). $$

Implementing multinomial logistic regression involves several critical steps that must be carefully executed to ensure the model's effectiveness. The process begins with data loading and preprocessing. We start by loading the multiclass dataset into the program. Since the target variable $y$ represents multiple classes, it needs to be converted into a format suitable for multiclass classification algorithms. This is achieved by one-hot encoding $y$ into a binary matrix $Y$ of size $n \times K$, where $n$ is the number of samples and $K$ is the number of classes. One-hot encoding transforms the categorical class labels into a binary vector representation, which facilitates the computation of probabilities for each class during model training. Additionally, standardizing the features is essential to ensure that all input variables contribute equally to the result, preventing any single feature from disproportionately influencing the model due to scale differences.

With the data prepared, we proceed to initialize the model parameters. We initialize the weight matrix $\mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times K}$ and the bias vector $\mathbf{b} \in \mathbb{R}^{K}$ with small random values, where $d$ is the number of features. These parameters will be iteratively updated during the training process to minimize the loss function.

Defining the softmax function is the next crucial step. The softmax function is used to convert the raw model outputs (logits) into probabilities that sum to one across all classes, which is necessary for multiclass classification. The implementation in Rust is as follows:

fn softmax(z: &Array2<f64>) -> Array2<f64> {

let max_z = z.map_axis(Axis(1), |row| row.fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, |a, &b| a.max(b)));

let exp_z = z - &max_z.insert_axis(Axis(1));

let exp_z = exp_z.mapv(f64::exp);

let sum_exp_z = exp_z.sum_axis(Axis(1));

&exp_z / &sum_exp_z.insert_axis(Axis(1))

}

This function stabilizes the computation by subtracting the maximum value in each row from the logits before exponentiating, which helps prevent numerical overflow.

Next, we compute the loss function, which measures the discrepancy between the predicted probabilities and the actual classes. The loss function for multinomial logistic regression is typically the negative log-likelihood, calculated as:

fn compute_loss(y_true: &Array2<f64>, y_pred: &Array2<f64>) -> f64 {

-(y_true * y_pred.mapv(f64::ln)).sum() / y_true.nrows() as f64

}

This function computes the average cross-entropy loss over all samples, providing a scalar value that reflects the model's performance.

To optimize the model parameters, we implement the gradient descent algorithm. The gradient descent function updates the weights and biases iteratively to minimize the loss function:

fn gradient_descent(

x: &Array2<f64>,

y: &Array2<f64>,

learning_rate: f64,

epochs: usize,

) -> (Array2<f64>, Array1<f64>) {

let (n_samples, n_features) = x.dim();

let n_classes = y.dim().1;

let mut w = Array2::<f64>::zeros((n_features, n_classes));

let mut b = Array1::<f64>::zeros(n_classes);

for epoch in 0..epochs {

let z = x.dot(&w) + &b;

let y_pred = softmax(&z);

let error = &y_pred - y;

let dw = x.t().dot(&error) / n_samples as f64;

let db = error.sum_axis(Axis(0)) / n_samples as f64;

w -= &(learning_rate * dw);

b -= &(learning_rate * db);

// Calculate and print loss every 100 epochs

if epoch % 100 == 0 {

let loss = compute_loss(y, &y_pred);

println!("Epoch {}: Loss = {}", epoch, loss);

}

}

(w, b)

}

In each iteration, the algorithm calculates the model's predictions, computes the error between the predicted probabilities and the actual labels, and updates the weights and biases based on the gradients of the loss function with respect to these parameters.

With the gradient descent function defined, we proceed to train the model using the training dataset:

let (w, b) = gradient_descent(&x_train, &y_train_one_hot, 0.01, 1000);

Here, we call the gradient_descent function with the standardized training features x_train, the one-hot encoded training labels y_train_one_hot, a learning rate of 0.01, and specify the number of epochs as 1000.

After training the model, we can make predictions on new data using the following function:

fn predict(x: &Array2<f64>, w: &Array2<f64>, b: &Array1<f64>) -> Array1<usize> {

let z = x.dot(w) + b;

let y_pred = softmax(&z);

y_pred.map_axis(Axis(1), |row| {

row.iter().enumerate().fold((0, 0.0), |(idx_max, val_max), (idx, &val)| {

if val > val_max { (idx, val) } else { (idx_max, val_max) }

}).0

})

}

let y_pred = predict(&x_test, &w, &b);

This function computes the predicted probabilities for each class and assigns each sample to the class with the highest probability, effectively performing the classification.

Applying multinomial logistic regression to datasets with more than two classes is straightforward using this implementation. For instance, the Iris dataset, which contains three classes of flowers, can be used to train the model. By feeding the model with this data, we enable it to classify observations into one of the multiple classes based on their features.

Evaluating the performance of the multinomial logistic regression model is essential to understand its effectiveness. For multiclass classification, performance metrics include accuracy, which measures the proportion of correctly classified samples. The confusion matrix is another valuable tool, represented as a $K \times K$ matrix where $\text{CM}_{i,j}$ indicates the number of instances of class $i$ that were predicted as class $j$. Additionally, precision, recall, and F1 score can be calculated for each class in a one-vs-rest manner, providing insights into the model's performance on a per-class basis.

Implementing ordinal logistic regression is more complex due to the cumulative probabilities and shared coefficients among the classes. The mathematical formulation involves modeling the cumulative probability for class $k$ as:

$$P(y \leq k | \mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\theta_k - \mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x})}},$$

for $k = 1, 2, \dots, K-1$. The probability of being in class kkk is then computed as:

$$P(y = k | \mathbf{x}) = P(y \leq k | \mathbf{x}) - P(y \leq k - 1 | \mathbf{x}),$$

with the boundary conditions $P(y \leq 0 | \mathbf{x}) = 0$ and $P(y \leq K | \mathbf{x}) = 1$.

The implementation steps for ordinal logistic regression begin with data preparation, where the ordinal target variable is encoded appropriately, and the features are standardized. During model training, we can use an ordinal regression package, such as the smartcore crate, or implement the model using optimization algorithms that handle the cumulative probabilities and shared coefficients. In the prediction phase, cumulative probabilities are computed, and the class is determined based on where the predicted probability falls between the defined thresholds. For evaluation, we use metrics suitable for ordinal data, such as accuracy and mean absolute error, and consider metrics that account for the ordered nature of the classes.

Implementing ordinal logistic regression in Rust may present challenges due to the limited availability of specialized crates for statistical models. However, it is possible to implement the model using similar techniques as multinomial logistic regression, with careful attention to handling cumulative probabilities and thresholds.

Evaluating the performance of both multinomial and ordinal logistic regression models is crucial. For multiclass classification, we can use macro-averaged metrics, which involve computing the metric independently for each class and then taking the average. Alternatively, micro-averaged metrics aggregate the contributions of all classes to compute the average metric. Analyzing the confusion matrix provides valuable insights into which classes are being misclassified and can highlight patterns in the errors, informing potential improvements to the model.

In conclusion, multinomial and ordinal logistic regression extend logistic regression's capabilities to handle more complex classification problems involving multiple classes and ordered outcomes. By understanding the mathematical foundations, such as the softmax function and cumulative probabilities, we can adapt logistic regression to a wide range of applications. Implementing these models in Rust involves meticulous handling of data structures and optimization algorithms. While Rust's ecosystem may not have as many ready-to-use libraries as other programming languages, its performance and safety make it a strong candidate for building efficient machine learning models. Evaluating the models using appropriate metrics ensures that we can accurately assess their performance and make informed decisions about their applicability to real-world problems.

5.6. Evaluation Metrics for Linear Models

Evaluation metrics are crucial for assessing the performance of machine learning models, allowing us to determine how well our models are performing and where improvements are needed. In the context of linear models, we focus on different metrics for regression and classification tasks, each serving a specific purpose in model evaluation.

For regression models, three commonly used metrics are Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and R-squared ($R^2$). MSE measures the average squared difference between the predicted and actual values. It is calculated as:

$$ \text{MSE} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2 $$

where $y_i$ represents the actual value, $\hat{y}_i$ is the predicted value, and nnn is the number of observations. MSE penalizes larger errors more severely due to the squaring of differences, making it sensitive to outliers.

RMSE is simply the square root of MSE:

$$ \text{RMSE} = \sqrt{\text{MSE}} $$

This metric provides an error measure in the same units as the target variable, making it more interpretable than MSE.

R-squared, or the coefficient of determination, indicates the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. It is calculated as:

$$ R^2 = 1 - \frac{\text{RSS}}{\text{TSS}} $$

where RSS is the residual sum of squares and TSS is the total sum of squares. An R-squared value of 1 indicates a perfect fit, while a value closer to 0 suggests that the model does not explain much of the variability in the target variable.

For classification models, key metrics include accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. Accuracy is the proportion of correctly classified instances out of the total instances:

$$\text{Accuracy} = \frac{\text{TP} + \text{TN}}{\text{TP} + \text{TN} + \text{FP} + \text{FN}}$$

where TP is true positives, TN is true negatives, FP is false positives, and FN is false negatives.

Precision measures the proportion of true positive predictions out of all positive predictions made:

$$ \text{Precision} = \frac{\text{TP}}{\text{TP} + \text{FP}} $$

Recall, or sensitivity, measures the proportion of true positives out of all actual positives:

$$ \text{Recall} = \frac{\text{TP}}{\text{TP} + \text{FN}} $$

The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both:

$$ \text{F1} = \frac{2 \cdot \text{Precision} \cdot \text{Recall}}{\text{Precision} + \text{Recall}} $$

Choosing the right metric depends on the problem at hand. For regression tasks where prediction accuracy is paramount, MSE, RMSE, and R-squared are appropriate. For classification tasks, especially when dealing with imbalanced classes, precision, recall, and F1 score provide a more nuanced evaluation of model performance.

In practice, implementing these evaluation metrics in Rust involves writing functions to compute each metric based on model predictions and actual values. Below are examples of how to implement and use these metrics for both linear regression and logistic regression models in Rust.

use nalgebra as na;

use na::{DMatrix, DVector};

use std::error::Error;

// Mean Squared Error

fn mean_squared_error(y_true: &DVector<f64>, y_pred: &DVector<f64>) -> f64 {

let residuals = y_true - y_pred;

residuals.dot(&residuals) / y_true.len() as f64

}

// Compute the mean of a DVector

fn mean(vector: &DVector<f64>) -> f64 {

vector.sum() / vector.len() as f64

}

// R-squared

fn r_squared(y_true: &DVector<f64>, y_pred: &DVector<f64>) -> f64 {

let mean_y = mean(y_true); // Compute mean of y_true

let ss_total = y_true.iter().map(|y| (y - mean_y).powi(2)).sum::<f64>();

let ss_residual = mean_squared_error(y_true, y_pred) * y_true.len() as f64;

1.0 - (ss_residual / ss_total)

}

// Accuracy

fn accuracy(y_true: &DVector<usize>, y_pred: &DVector<usize>) -> f64 {

let correct = y_true.iter().zip(y_pred.iter()).filter(|&(true_val, pred_val)| true_val == pred_val).count();

correct as f64 / y_true.len() as f64

}

// Precision

fn precision(y_true: &DVector<usize>, y_pred: &DVector<usize>, class: usize) -> f64 {

let tp = y_true.iter().zip(y_pred.iter()).filter(|&(true_val, pred_val)| *true_val == class && *pred_val == class).count() as f64;

let fp = y_pred.iter().filter(|&&pred_val| pred_val == class).count() as f64;

if fp == 0.0 { 0.0 } else { tp / fp }

}

// Recall

fn recall(y_true: &DVector<usize>, y_pred: &DVector<usize>, class: usize) -> f64 {

let tp = y_true.iter().zip(y_pred.iter()).filter(|&(true_val, pred_val)| *true_val == class && *pred_val == class).count() as f64;

let fn_count = y_true.iter().filter(|&&true_val| true_val == class).count() as f64;

if (tp + fn_count) == 0.0 { 0.0 } else { tp / (tp + fn_count) }

}

// F1 Score

fn f1_score(y_true: &DVector<usize>, y_pred: &DVector<usize>, class: usize) -> f64 {

let prec = precision(y_true, y_pred, class);

let rec = recall(y_true, y_pred, class);

if (prec + rec) == 0.0 { 0.0 } else { 2.0 * (prec * rec) / (prec + rec) }

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

// Sample regression data

let y_true = DVector::from_row_slice(&[3.0, 4.0, 5.0]);

let y_pred = DVector::from_row_slice(&[2.9, 4.1, 5.2]);

let mse = mean_squared_error(&y_true, &y_pred);

let r2 = r_squared(&y_true, &y_pred);

println!("Mean Squared Error: {:.2}", mse);

println!("R-squared: {:.2}", r2);

// Sample classification data

let y_true_class = DVector::from_row_slice(&[0, 1, 1, 0]);

let y_pred_class = DVector::from_row_slice(&[0, 1, 0, 0]);

let acc = accuracy(&y_true_class, &y_pred_class);

let prec = precision(&y_true_class, &y_pred_class, 1);

let rec = recall(&y_true_class, &y_pred_class, 1);

let f1 = f1_score(&y_true_class, &y_pred_class, 1);

println!("Accuracy: {:.2}", acc);

println!("Precision: {:.2}", prec);

println!("Recall: {:.2}", rec);

println!("F1 Score: {:.2}", f1);

Ok(())

}

In this implementation, functions for calculating MSE, R-squared, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score are provided. The mean_squared_error and r_squared functions evaluate regression models, while accuracy, precision, recall, and f1_score evaluate classification models. These metrics are crucial for understanding model performance and guiding improvements, ensuring that the models are both accurate and effective in their respective tasks.

By effectively implementing and interpreting these metrics, you can better assess the quality of your linear models and make informed decisions to enhance their performance and applicability to real-world problems.

5.7. Conclusion

Chapter 5 has provided an in-depth exploration of linear models for regression and classification, covering both theoretical foundations and practical implementations in Rust. By mastering these techniques, you will be well-prepared to tackle a variety of machine learning problems with models that are both interpretable and efficient.

5.7.1 Further Learning with GenAI

The following prompts are designed to deepen your understanding of linear models, encourage practical implementation in Rust, and foster critical analysis of model performance.

Explain the fundamental principles of linear regression. How does the least squares method estimate the coefficients, and what assumptions underlie the linear regression model? Implement linear regression from scratch in Rust and apply it to a real-world dataset.

Discuss the problem of overfitting in linear regression. How do bias and variance trade-offs influence model performance, and what techniques can be used to mitigate overfitting, such as regularization methods like Ridge and Lasso regression? Implement these regularization techniques in Rust and compare their effectiveness on a dataset.

Analyze the role of the normal equation in linear regression. How does it derive the closed-form solution for the coefficients, and under what conditions might this approach be infeasible? Implement the normal equation method in Rust and explore its limitations with large datasets or ill-conditioned matrices.

Explore the use of gradient descent in linear regression. How does this iterative optimization method work, and when is it preferred over the normal equation? Implement batch gradient descent, stochastic gradient descent, and mini-batch gradient descent in Rust, and compare their convergence and performance.

Discuss the concept of feature scaling and its importance in linear models. How do techniques like standardization and normalization affect the convergence of optimization algorithms? Implement feature scaling in Rust and analyze its impact on the training process of a linear regression model.

Explain the principles of logistic regression for classification tasks. How does the logistic function transform linear combinations of features into probability estimates? Implement logistic regression from scratch in Rust and apply it to a binary classification problem.

Discuss the use of evaluation metrics for classification models, such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. How do these metrics inform the performance of logistic regression models? Implement these metrics in Rust and evaluate your logistic regression model on a test dataset.

Analyze the concept of decision boundaries in logistic regression. How do the model coefficients determine the separation between classes, and how can we visualize this boundary? Implement visualization tools in Rust to plot the decision boundary of a logistic regression model on a two-dimensional dataset.

Explore the extension of logistic regression to multiclass classification through multinomial logistic regression and the softmax function. How does this generalization work, and what are the differences compared to binary logistic regression? Implement multinomial logistic regression in Rust and apply it to a multiclass dataset.

Discuss the role of regularization in logistic regression. How do L1 and L2 regularization help prevent overfitting, and what are the effects on the model coefficients? Implement regularized logistic regression in Rust and compare the performance with and without regularization on a classification problem.

Analyze the impact of imbalanced datasets on logistic regression models. What challenges arise, and how can techniques like resampling or adjusting class weights help address them? Implement these strategies in Rust and evaluate their effectiveness on an imbalanced classification dataset.

Explore the use of polynomial features in linear regression. How does transforming input features into higher-degree polynomials enable the model to capture nonlinear relationships? Implement polynomial regression in Rust and apply it to a dataset with nonlinear patterns.

Discuss the concept of basis functions and kernel methods in linear models. How can these techniques extend linear models to handle complex, nonlinear data? Implement a kernelized linear regression in Rust using basis functions, and analyze its performance on a suitable dataset.

Explain the assumptions underlying linear regression and logistic regression models. How do violations of these assumptions affect model performance, and what diagnostic tools can be used to detect them? Implement residual analysis in Rust for linear regression to assess assumption adherence.

Discuss the challenges of multicollinearity in linear models. How does the presence of highly correlated features impact the model coefficients and predictions? Implement variance inflation factor (VIF) calculation in Rust to detect multicollinearity and explore strategies to mitigate its effects.

Analyze the use of feature selection techniques in linear models. How can methods like forward selection, backward elimination, and regularization aid in selecting relevant features? Implement a feature selection algorithm in Rust and apply it to improve a linear regression model.

Explore the use of robust regression methods to handle outliers. How do techniques like RANSAC and Huber regression enhance model robustness? Implement a robust regression algorithm in Rust and compare its performance to ordinary least squares regression on a dataset with outliers.

Discuss the interpretation of model coefficients in linear and logistic regression. How can we understand the influence of each feature on the target variable, and what considerations are important when making these interpretations? Implement tools in Rust to extract and interpret model coefficients.

Explain the concept of cross-validation in model evaluation. How does k-fold cross-validation provide a more reliable estimate of model performance? Implement cross-validation in Rust and use it to assess the generalization capability of your linear models.