Chapter 12

Density Estimation and Generative Models

"What we can not create, we do not understand" — Richard Feynman

Chapter 12 of MLVR provides an in-depth exploration of density estimation and generative models, fundamental techniques in understanding and generating data distributions. The chapter begins with an introduction to density estimation, covering both parametric and non-parametric methods, and the challenges involved in choosing the right approach. It then delves into generative models, exploring Gaussian Mixture Models, Variational Autoencoders, and Generative Adversarial Networks, highlighting their theoretical foundations and practical implementation using Rust. The chapter concludes with a discussion on evaluating these models, emphasizing the importance of metrics like log-likelihood and FID in assessing the quality of generated data. By the end of this chapter, readers will have a comprehensive understanding of how to implement and evaluate density estimation and generative models using Rust, enabling them to apply these techniques to complex machine learning tasks.

12.1. Introduction to Density Estimation

In statistical analysis and machine learning, density estimation serves as a foundational method for understanding the underlying distribution of data. The goal of density estimation is to estimate the probability density function (PDF) of a random variable based on observed data points, allowing practitioners to infer the structure of the data without assuming prior knowledge of the distribution. This process is essential for tasks such as anomaly detection, where unusual patterns must be identified; clustering, which requires an understanding of data distribution; and generative modeling, where sampling from estimated densities enables the creation of new data points consistent with the observed dataset.

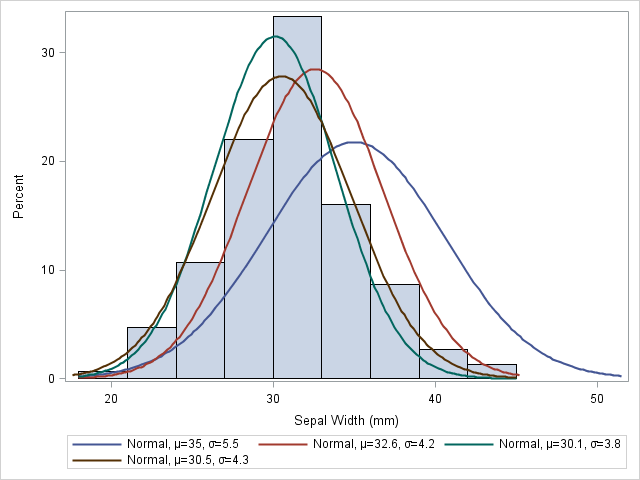

Figure 1: Illustration of density estimation.

Density estimation can be categorized into two primary approaches: parametric and non-parametric. Parametric methods involve assuming that the data follows a specific distribution, such as a Gaussian or exponential distribution, and then estimating the parameters of that distribution based on the data. These methods are typically efficient when the assumed distribution aligns closely with the true underlying distribution, but they can fail when the actual distribution deviates from the assumed form. For example, given a set of data points that resemble a normal distribution, parametric methods would involve estimating the mean μ\\muμ and variance $\sigma^2$ of the Gaussian distribution using maximum likelihood estimation or other parameter estimation techniques.

In contrast, non-parametric methods make fewer assumptions about the underlying distribution. Instead of fitting the data to a predefined form, non-parametric methods allow the data itself to dictate the shape of the density function. Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) is one of the most commonly used non-parametric techniques. Given a set of data points $x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n$, the KDE method constructs a smooth estimate of the PDF by centering a kernel function $K$ at each data point and summing the contributions of these kernels. The KDE estimator $\hat{f}(x)$ at a point $x$ is defined as:

$$ \hat{f}(x) = \frac{1}{n h} \sum_{i=1}^{n} K\left( \frac{x - x_i}{h} \right) $$

where $n$ is the number of data points, $h$ is the bandwidth (or smoothing parameter), and $K$ is the kernel function. The kernel function $K$ must satisfy the properties of a probability density function, i.e., it must integrate to 1 and be non-negative. Common choices for the kernel include the Gaussian kernel:

$$ K(u) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{u^2}{2}} $$

The bandwidth parameter $h$ plays a critical role in controlling the smoothness of the resulting density estimate. If $h$ is too small, the estimate will be overly sensitive to individual data points, resulting in a jagged, overfit density that captures noise in the data. On the other hand, if $h$ is too large, the estimate may oversmooth the data, missing important features and trends in the distribution. Thus, selecting an appropriate bandwidth is crucial for balancing bias and variance in the density estimation process. One common method for bandwidth selection is Silverman's rule of thumb, which provides an automatic way to choose the bandwidth based on the data’s variance and sample size:

$$ h = 1.06 \sigma n^{-1/5} $$

where $\sigma$ is the standard deviation of the data and nnn is the number of data points.

The bias-variance tradeoff is central to the problem of density estimation. A model with low bias but high variance is prone to overfitting, as it captures random fluctuations or noise in the data. In contrast, a model with high bias but low variance may underfit the data by failing to capture its true structure. This tradeoff is particularly pronounced in non-parametric methods like KDE, where the complexity of the model (in this case, controlled by the bandwidth $h$) must be carefully tuned to strike the right balance.

Density estimation becomes even more challenging in high-dimensional spaces due to the "curse of dimensionality." As the dimensionality increases, the volume of the space grows exponentially, causing the data to become sparse. In such cases, it becomes difficult to reliably estimate densities, as the data points are spread too thinly across the space to provide meaningful estimates. This issue often necessitates dimensionality reduction techniques or advanced methods tailored for high-dimensional data.

In the implementation of Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) using Rust, we will focus on efficiently applying this method to a dataset and visualizing the results. A Rust implementation can leverage the language’s performance and safety features, allowing for optimized computation of the density estimate while ensuring correctness through strict type checks. By selecting an appropriate kernel function and tuning the bandwidth parameter, we can create a flexible and robust density estimation tool that adapts to various data distributions. In this chapter, we will walk through the Rust implementation of KDE, demonstrating how to construct the estimator, select the bandwidth, and visualize the results for practical applications.

The concept of density estimation extends to generative models, where the estimated density is used to sample new data points. Generative models such as Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) rely on learning the underlying data distribution to generate synthetic data that resembles the training set. These models often use density estimation as a core component to approximate the distribution of complex, high-dimensional datasets. In subsequent sections, we will explore how density estimation forms the foundation for various generative models and how Rust’s ecosystem can support efficient implementations of these models.

To get started with our implementation, let's create a Rust project and add the necessary dependencies in the Cargo.toml file. We will need ndarray for numerical operations and plotters for visualization. Here is a sample Cargo.toml configuration:

// Append Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

ndarray = "0.16.1"

plotters = "0.3.7"

Next, we can implement a simple kernel density estimator in Rust. Below is a basic implementation of KDE, using a Gaussian kernel function:

use ndarray::Array1;

use ndarray::Array;

use std::f64::consts::PI;

use plotters::prelude::*;

fn gaussian_kernel(x: f64) -> f64 {

(1.0 / (2.0 * PI).sqrt()) * (-0.5 * x.powi(2)).exp()

}

fn kernel_density_estimate(data: &Array1<f64>, points: &Array1<f64>, bandwidth: f64) -> Array1<f64> {

let n = data.len();

let m = points.len();

let mut density = Array::zeros(m);

for i in 0..m {

for j in 0..n {

let x = (points[i] - data[j]) / bandwidth;

density[i] += gaussian_kernel(x);

}

density[i] /= (n as f64) * bandwidth; // Normalize

}

density

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

// Sample data for KDE

let data = Array1::from_vec(vec![

0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5

]);

// Points where we want to estimate the density

let points = Array1::linspace(0.0, 2.0, 100); // 100 points between 0 and 2

// Bandwidth for KDE

let bandwidth = 0.1;

// Perform KDE

let density = kernel_density_estimate(&data, &points, bandwidth);

// Plot the result using Plotters

let root = BitMapBackend::new("kde_plot.png", (640, 480)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Kernel Density Estimate", ("sans-serif", 50))

.margin(20)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(0.0..2.0, 0.0..density.iter().cloned().fold(0./0., f64::max))?;

chart.configure_mesh().draw()?;

chart.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

points.iter().cloned().zip(density.iter().cloned()),

&RED,

))?

.label("KDE")

.legend(|(x, y)| PathElement::new(vec![(x, y), (x + 10, y)], &RED));

chart.configure_series_labels().border_style(&BLACK).draw()?;

// Save the plot as an image

root.present()?;

println!("KDE plot saved to kde_plot.png");

Ok(())

}

In this code, the gaussian_kernel function defines the Gaussian kernel, while the kernel_density_estimate function computes the density estimates for the specified points. It iterates over each point where we want to estimate the density and sums the contributions from all observed data points, normalized by the number of observations and the bandwidth.

To visualize the estimated density, we can integrate plotters to create a simple plot of the density estimates. Here is how we can visualize the results:

use ndarray::Array1;

use ndarray::Array;

use plotters::prelude::*;

use std::f64::consts::PI;

use plotters::style::IntoFont;

// The Gaussian kernel function

fn gaussian_kernel(x: f64) -> f64 {

(1.0 / (2.0 * PI).sqrt()) * (-0.5 * x.powi(2)).exp()

}

// The kernel density estimation function

fn kernel_density_estimate(data: &Array1<f64>, points: &Array1<f64>, bandwidth: f64) -> Array1<f64> {

let n = data.len();

let m = points.len();

let mut density = Array::zeros(m);

for i in 0..m {

for j in 0..n {

let x = (points[i] - data[j]) / bandwidth;

density[i] += gaussian_kernel(x);

}

density[i] /= (n as f64) * bandwidth; // Normalize

}

density

}

// Plotting the estimated density function

fn plot_density(estimated_density: &Array1<f64>, points: &Array1<f64>) {

let root = BitMapBackend::new("density_estimate.png", (640, 480)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

let min_x = *points.iter().min_by(|a, b| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap()).unwrap();

let max_x = *points.iter().max_by(|a, b| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap()).unwrap();

let max_y = *estimated_density.iter().max_by(|a, b| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap()).unwrap();

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Kernel Density Estimation", ("sans-serif", 50).into_font())

.margin(5)

.x_label_area_size(30)

.y_label_area_size(30)

.build_cartesian_2d(min_x..max_x, 0.0..max_y)

.unwrap();

chart.configure_series_labels().background_style(&WHITE).border_style(&BLACK).draw().unwrap();

chart.draw_series(LineSeries::new(

points.iter().zip(estimated_density.iter()).map(|(&x, &y)| (x, y)),

&RED

)).unwrap();

}

fn main() {

let data = Array1::from_vec(vec![1.0, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 5.0]);

let points = Array1::linspace(0.0, 6.0, 100);

let bandwidth = 0.5;

let density = kernel_density_estimate(&data, &points, bandwidth);

plot_density(&density, &points);

}

In this main function, we generate a sample dataset and define a range of points for which we want to estimate the density. The plot_density function creates a plot using the plotters library, displaying the resulting density estimates over the specified range. The output will be a PNG file titled "density_estimate.png" that visually represents the estimated density using KDE.

Through this exploration of density estimation and the implementation of Kernel Density Estimation in Rust, we gain valuable insights into how to estimate the distribution of data points effectively. This foundational understanding will serve as a stepping stone as we continue our journey into generative models and more advanced density estimation techniques in the following sections.

12.2. Parametric Density Estimation

Parametric density estimation is a fundamental approach in statistics and machine learning, characterized by the assumption that the data follows a specific, known distribution, often described by a finite set of parameters. The key idea is that the distribution of a dataset can be succinctly summarized using a small number of parameters, which leads to more efficient computations and simpler models. This simplicity, however, comes with trade-offs: while parametric methods are computationally efficient and effective when the data fits the assumed distribution well, they can lead to poor performance when the underlying distribution deviates from these assumptions.

One of the most commonly used parametric models is the Gaussian distribution, also known as the normal distribution. A Gaussian distribution is fully characterized by two parameters: the mean $\mu$, which represents the central tendency of the data, and the variance $\sigma^2$, which captures the spread or variability of the data. The probability density function (PDF) for a Gaussian distribution is given by:

$$ f(x \mid \mu, \sigma^2) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \exp\left( -\frac{(x - \mu)^2}{2\sigma^2} \right) $$

Here, $x$ represents a data point, while $\mu$ and $\sigma^2$ are the parameters to be estimated from the data. The Gaussian distribution is particularly useful due to its mathematical properties, such as being the limit distribution of many types of data via the central limit theorem. This property makes it applicable in a wide range of practical scenarios, especially when the true underlying distribution is unknown but is believed to approximate normality.

More broadly, parametric methods are not limited to the Gaussian distribution. They extend to the exponential family of distributions, which provides a general framework for many common distributions used in machine learning and statistics. The exponential family includes distributions like the Gaussian, Poisson, exponential, and Bernoulli distributions, all of which can be written in a common form:

$$ f(x \mid \theta) = h(x) \exp\left( \eta(\theta)^\top T(x) - A(\theta) \right) $$

where $\theta$ is the parameter vector, $h(x)$ is the base measure, $\eta(\theta)$ is the natural parameter, $T(x)$ is the sufficient statistic, and $A(\theta)$ is the log partition function. The exponential family is powerful because it allows for a unified treatment of a wide range of distributions, and many of these distributions exhibit desirable properties such as conjugacy in Bayesian inference, which simplifies the process of parameter estimation.

The process of estimating the parameters of a parametric model is often performed using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). MLE is a statistical method that seeks to find the parameter values that maximize the likelihood function, which measures the probability of observing the given data under a specified model. Given a dataset $\{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\}$, the likelihood function for a parametric model with parameters $\theta$ is defined as:

$$ L(\theta \mid x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} f(x_i \mid \theta) $$

In practice, it is often easier to work with the log-likelihood, which turns the product into a sum:

$$ \log L(\theta \mid x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log f(x_i \mid \theta) $$

The goal of MLE is to find the parameter θ\\thetaθ that maximizes this log-likelihood function. For example, in the case of a Gaussian distribution, the log-likelihood function can be written as:

$$ \log L(\mu, \sigma^2 \mid x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n) = -\frac{n}{2} \log(2\pi \sigma^2) - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i - \mu)^2 $$

Maximizing this expression with respect to $\mu$ and $\sigma^2$ leads to the well-known estimators for the mean and variance:

$$ \hat{\mu} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i, \quad \hat{\sigma}^2 = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i - \hat{\mu})^2 $$

MLE is a widely used method for parameter estimation because it has several desirable statistical properties. First, MLE estimators are consistent, meaning that as the sample size increases, the estimates converge to the true parameter values. Second, MLE estimators are asymptotically normal, implying that for large samples, the distribution of the estimator approaches a normal distribution. This property allows for straightforward hypothesis testing and construction of confidence intervals. Finally, under certain regularity conditions, MLE estimators are efficient, meaning that they achieve the lowest possible variance among unbiased estimators, as described by the Cramér-Rao lower bound.

Figure 2: Illustration of MLE using Iris dataset.

Despite the advantages of parametric density estimation, it is important to be aware of its limitations. The primary drawback is that parametric models rely on the assumption that the data follows a specific distribution. If the true underlying distribution deviates significantly from this assumption, the model may fail to capture important aspects of the data, leading to biased estimates and poor generalization. This risk is particularly pronounced in real-world scenarios where data distributions are often complex and do not conform neatly to standard distributions like the Gaussian or Poisson. In such cases, non-parametric methods, which do not rely on strong assumptions about the form of the distribution, may provide more flexible and accurate estimates.

However, parametric models retain their importance due to their simplicity and interpretability. In many applications, such as anomaly detection or model-based reinforcement learning, the computational efficiency and ease of interpretation offered by parametric models make them an attractive choice. Furthermore, parametric models often serve as the basis for more complex generative models, such as Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs), which extend the simplicity of parametric estimation to handle more intricate data distributions.

In practical terms, implementing parametric density estimation in Rust involves creating a model that can fit the chosen distribution to a dataset. Suppose we want to implement Gaussian density estimation. We will need to calculate the mean and variance of the data and then use these parameters to evaluate the probability density function (PDF) of the Gaussian distribution. Below is a Rust implementation that demonstrates how to perform parametric density estimation using the Gaussian model:

use ndarray;

use ndarray::Array1;

use std::f64;

struct Gaussian {

mean: f64,

variance: f64,

}

impl Gaussian {

fn new(data: &Array1<f64>) -> Self {

let mean = data.mean().unwrap();

let variance = data.var(0.0);

Gaussian { mean, variance }

}

fn pdf(&self, x: f64) -> f64 {

let coeff = 1.0 / ((2.0 * f64::consts::PI * self.variance).sqrt());

let exponent = -((x - self.mean).powi(2)) / (2.0 * self.variance);

coeff * exponent.exp()

}

fn log_likelihood(&self, data: &Array1<f64>) -> f64 {

data.iter()

.map(|&x| self.pdf(x).ln())

.sum()

}

}

fn main() {

let data = Array1::from_vec(vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0]);

let gaussian_model = Gaussian::new(&data);

println!("Estimated Mean: {}", gaussian_model.mean);

println!("Estimated Variance: {}", gaussian_model.variance);

let test_value = 3.0;

println!("PDF at {}: {}", test_value, gaussian_model.pdf(test_value));

println!("Log-likelihood: {}", gaussian_model.log_likelihood(&data));

}

In this implementation, we create a Gaussian struct that holds the parameters mean and variance. The new method computes these parameters from the input data. The pdf method computes the probability density function for a given value, while the log_likelihood method calculates the log-likelihood of the observed data under the Gaussian model.

When applying this model to different datasets, we can analyze the fit of the Gaussian model by visualizing the data along with the estimated density. It's essential to evaluate not just the statistical metrics but also to perform graphical diagnostics, such as Q-Q plots or histograms overlayed with the estimated density curve. Such analyses can reveal inadequacies of the parametric model and inform decisions about whether to stick with the Gaussian assumption or explore other parametric or non-parametric methods.

In summary, parametric density estimation offers a robust framework for understanding and modeling the distribution of data. Through the lens of simplicity and flexibility, and with the guiding principle of maximum likelihood estimation, practitioners can effectively fit models to data while being mindful of their assumptions. By implementing these concepts in Rust, we leverage the language's performance and safety features, paving the way for efficient and reliable machine learning applications. As we proceed in this chapter, we will delve deeper into various parametric models, exploring their strengths and limitations, and applying them to real-world datasets to solidify our understanding of density estimation techniques.

12.3. Non-Parametric Density Estimation

Non-parametric density estimation plays a critical role in statistical analysis, especially in machine learning applications where the underlying distribution of the data may not conform to the assumptions of parametric methods. Unlike parametric techniques, which assume a specific form for the distribution (such as Gaussian or exponential), non-parametric methods allow for much greater flexibility by making fewer assumptions about the shape of the data’s distribution. This flexibility is particularly valuable in machine learning tasks such as clustering, classification, and anomaly detection, where capturing the true underlying data distribution is crucial for model accuracy.

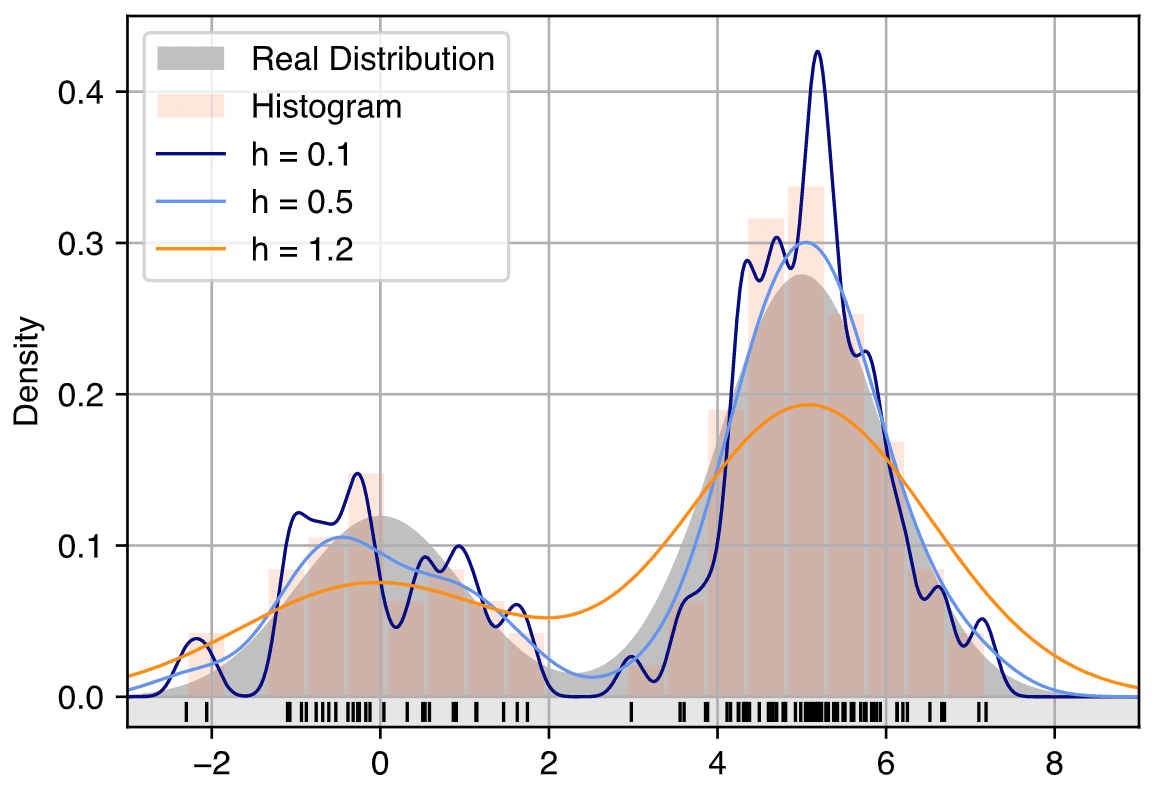

Figure 3: Illustration of KDE density estimation.

One of the most prominent non-parametric density estimation methods is Kernel Density Estimation (KDE). The fundamental concept behind KDE is to estimate the probability density function (PDF) of a random variable by placing a kernel function—a smooth and continuous function—at each data point and then averaging these contributions to form a smooth density estimate. Mathematically, the KDE for a given point $x$ is defined as:

$$ \hat{f}(x) = \frac{1}{n h} \sum_{i=1}^{n} K\left( \frac{x - x_i}{h} \right) $$

Here, $n$ represents the number of data points, $h$ is the bandwidth parameter that controls the smoothness of the estimate, and $K$ is the kernel function. The kernel $K$ must satisfy the properties of a probability density function, such as non-negativity and integrating to one over the entire space. The role of the kernel is to smooth the contribution of each data point, and the overall density estimate is the sum of these smoothed values.

Commonly used kernels include the Gaussian kernel:

$$ K(u) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp\left( -\frac{u^2}{2} \right) $$

as well as the Epanechnikov and Uniform kernels. The choice of kernel affects the smoothness of the resulting density estimate, but in practice, the kernel selection is often less critical than the choice of the bandwidth $h$, which governs the width of the kernel function. The bandwidth determines how much each data point influences its surroundings. A small bandwidth leads to a more localized estimate that can capture fine details and even noise, potentially leading to overfitting. Conversely, a large bandwidth results in a smoother estimate but can oversmooth the distribution, potentially missing important structures such as peaks or multimodal behavior.

One of the main challenges in applying KDE is the selection of the bandwidth parameter. The bandwidth is a critical factor because it determines the trade-off between bias and variance in the estimation. A smaller bandwidth reduces bias but increases variance, while a larger bandwidth decreases variance but introduces bias. The optimal bandwidth minimizes the mean squared error (MSE) of the estimate, balancing the bias and variance. Several methods exist for selecting the bandwidth, including:

Cross-validation: A method that involves dividing the dataset into training and validation sets and selecting the bandwidth that minimizes the error on the validation set.

Plug-in methods: These methods estimate the optimal bandwidth by approximating the underlying distribution’s second derivative, often involving complex calculations.

Rules of thumb: A simpler approach is to use heuristic methods such as Silverman’s rule of thumb, which provides an automatic bandwidth based on the data’s variance and sample size:

$$ h = 1.06 \sigma n^{-1/5} $$

where $\sigma$ is the standard deviation of the data, and $n$ is the number of data points. Silverman’s rule is useful in practice but may not be optimal in cases where the data has a complex or multimodal distribution.

In addition to KDE, another prominent non-parametric method is the nearest-neighbor approach. Nearest-neighbor density estimation methods estimate the local density at a point based on the distances to the $k$-nearest neighbors. For a given point $x$, the density estimate is proportional to the inverse of the volume of the space around $x$ that contains its $k$-nearest neighbors. Mathematically, the density estimate can be written as:

$$ \hat{f}(x) = \frac{k}{n V(x)} $$

where $V(x)$ is the volume of the region containing the $k$-nearest neighbors of $x$, and $k$ is the number of neighbors. The advantage of nearest-neighbor methods lies in their ability to adapt to the local structure of the data. In regions where the data is sparse, the nearest-neighbor method can adapt by considering a larger volume, while in dense regions, the method focuses on smaller neighborhoods. This adaptability makes nearest-neighbor methods particularly useful in high-dimensional spaces where the data may exhibit complex structures.

However, nearest-neighbor methods also have their challenges. Like KDE, they are sensitive to the choice of parameters, in this case, the number of neighbors $k$. A small $k$ can lead to a noisy estimate, while a large $k$ may oversmooth the data. Furthermore, in high-dimensional spaces, the volume of the space grows exponentially with the number of dimensions, leading to sparsity in the data and making density estimation more difficult. This issue is often referred to as the "curse of dimensionality."

To address these challenges, advanced techniques such as adaptive bandwidth KDE or variable $k$-nearest-neighbor methods have been developed. Adaptive bandwidth KDE adjusts the bandwidth locally based on the density of the data, providing more smoothing in regions with sparse data and less smoothing in regions with dense data. Similarly, variable $k$-nearest-neighbor methods adjust the number of neighbors based on the local density, providing more flexibility in high-dimensional or highly non-uniform datasets.

In this chapter, we will implement non-parametric density estimation techniques using Rust, focusing on the efficient computation of KDE and nearest-neighbor density estimation. Rust’s performance and memory safety features make it an ideal language for implementing these computationally intensive methods, allowing for precise control over memory and computational resources. We will explore practical examples, including the selection of appropriate kernels and bandwidth parameters, and visualize the resulting density estimates to illustrate how non-parametric methods can capture complex data distributions.

By leveraging these non-parametric techniques, we can build models that are more flexible and capable of capturing intricate data structures, which are essential in many machine learning tasks. Furthermore, we will discuss the limitations and potential solutions to challenges such as high dimensionality, providing a comprehensive view of non-parametric density estimation techniques in modern machine learning.

To illustrate non-parametric density estimation using KDE in Rust, we can implement a simple example. First, ensure you have the necessary dependencies in your Cargo.toml file. For this demonstration, we will use the ndarray crate for numerical operations and ndarray-rand for generating random samples.

[dependencies]

ndarray = "0.15.4"

ndarray-rand = "0.14.0"

Next, we will create a module for Kernel Density Estimation. The following code demonstrates a basic implementation of KDE:

use ndarray::Array1;

use ndarray_rand::rand_distr::Uniform;

use ndarray_rand::RandomExt;

fn gaussian_kernel(x: f64) -> f64 {

(1.0 / (2.0 * std::f64::consts::PI).sqrt()) * (-0.5 * x.powi(2)).exp()

}

fn kernel_density_estimation(data: &Array1<f64>, bandwidth: f64, x: f64) -> f64 {

let n = data.len() as f64;

let mut sum = 0.0;

for &point in data.iter() {

let kernel_value = gaussian_kernel((x - point) / bandwidth);

sum += kernel_value;

}

sum / (n * bandwidth)

}

fn main() {

let n_samples = 1000;

let data: Array1<f64> = Array1::random(n_samples, Uniform::new(-3.0, 3.0));

let bandwidth = 0.5;

let x_values: Vec<f64> = (-3..=3).map(|x| x as f64 * 0.1).collect();

let density_estimates: Vec<f64> = x_values.iter()

.map(|&x| kernel_density_estimation(&data, bandwidth, x))

.collect();

// Here you could plot the density estimates using a plotting library

}

In this code snippet, we define a Gaussian kernel function and a kernel_density_estimation function that computes the density estimate for a given value of x. We generate random samples from a uniform distribution and then apply the KDE to compute density estimates across a range of x-values.

To experiment with different bandwidth parameters, one might iterate through a range of values and observe the effect on the density estimate. This flexibility allows practitioners to optimize their models based on the specific characteristics of their datasets.

In summary, non-parametric density estimation techniques like KDE and nearest-neighbor methods provide robust tools for understanding complex data distributions. They offer the flexibility required to analyze real-world data effectively. However, careful attention must be paid to bandwidth selection in KDE to avoid common pitfalls associated with overfitting or oversmoothing. Through practical implementations in Rust, we can harness the power of these non-parametric approaches to enhance our machine learning endeavors.

12.4. Generative Models Overview

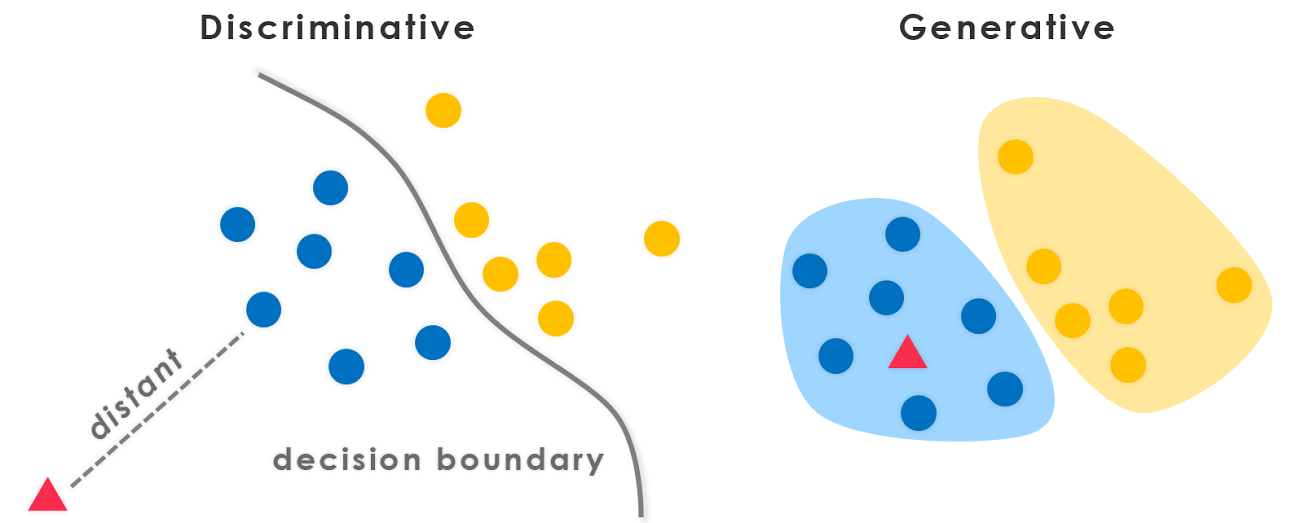

Generative models are a fundamental class of models in machine learning, focused on learning the joint probability distribution $P(X, Y)$ of the data, as opposed to discriminative models that focus on learning the conditional probability $P(Y \mid X)$. The generative approach allows these models to not only classify data but also to synthesize new examples that resemble the original dataset. This ability to generate data makes generative models particularly powerful for a wide range of applications, from image and text generation to data augmentation and unsupervised learning.

The distinction between generative and discriminative models is crucial for understanding their respective roles in machine learning. Discriminative models, such as logistic regression and support vector machines, focus on learning decision boundaries to distinguish between different classes. Generative models, by contrast, aim to model how the data was generated by capturing the distribution of both input features $X$ and the associated labels $Y$, if any. By learning the full distribution $P(X, Y)$, generative models can be used to sample new data points $X$ from the learned distribution, which can be invaluable in tasks such as anomaly detection, image synthesis, and reinforcement learning.

Figure 4: Discriminative vs Generative models

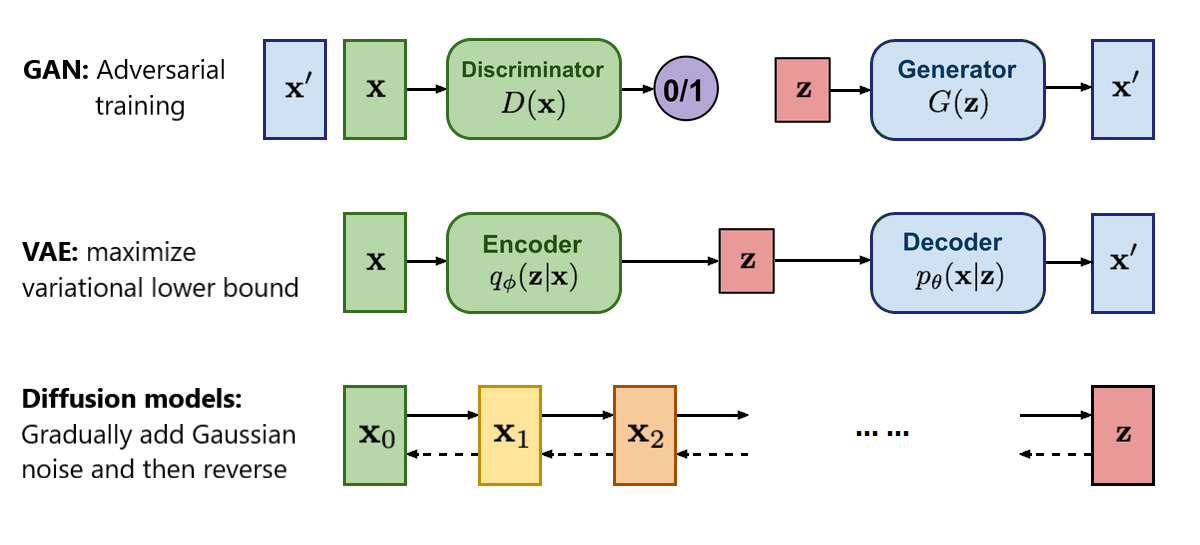

A wide array of generative models exists, each with its distinct methodology and advantages. Among the most common approaches are Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs).

Gaussian Mixture Models are a probabilistic model that assumes the data is generated from a mixture of several Gaussian distributions, each characterized by its own mean and covariance matrix. The probability density function (PDF) of a GMM with $k$ components can be written as:

$$ P(X) = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \pi_i \mathcal{N}(X \mid \mu_i, \Sigma_i) $$

where $\pi_i$ are the mixing coefficients (which sum to 1), $\mathcal{N}(X \mid \mu_i, \Sigma_i)$ represents the Gaussian distribution for the iii-th component with mean $\mu_i$ and covariance $\Sigma_i$, and $k$ is the number of components in the mixture. GMMs can be fit to data using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm, which iteratively estimates the parameters of the model to maximize the likelihood of the observed data.

One of the strengths of GMMs lies in their ability to approximate complex, multimodal distributions through a combination of simple Gaussian components. This makes GMMs particularly useful in clustering tasks, where the data naturally divides into groups, each of which can be modeled by a separate Gaussian distribution. Additionally, by learning the mixture of distributions, GMMs can generate new data points by sampling from the learned Gaussian components.

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) represent a more sophisticated generative approach, blending deep learning with probabilistic inference. Unlike GMMs, which rely on predefined components, VAEs use neural networks to learn a latent representation of the data that facilitates generation. The generative process in a VAE involves two key components: an encoder network that maps input data $X$ to a latent variable $z$, and a decoder network that reconstructs the data from $z$. The encoder approximates the posterior distribution $q(z \mid X)$, and the decoder defines the likelihood $p(X \mid z)$.

The objective in a VAE is to maximize a lower bound on the log-likelihood of the data, known as the evidence lower bound (ELBO):

$$ \log P(X) \geq \mathbb{E}_{q(z \mid X)} \left[ \log p(X \mid z) \right] - D_{KL} \left( q(z \mid X) \parallel p(z) \right) $$

where $D_{KL}$ is the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the approximate posterior $q(z \mid X)$ and the prior distribution $p(z)$, which is typically chosen to be a standard Gaussian. The first term of the ELBO encourages the model to accurately reconstruct the data, while the second term regularizes the latent space to follow the prior distribution, ensuring that the latent space is well-structured for generation.

VAEs excel in generating high-dimensional, complex data such as images and text. By learning a latent representation, VAEs can sample from the learned distribution to generate new data points. The probabilistic nature of the VAE framework also makes it suitable for capturing uncertainty in the data, making VAEs a powerful tool in unsupervised and semi-supervised learning tasks.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) introduce a fundamentally different approach to generative modeling through a game-theoretic framework. In a GAN, two neural networks—the generator and the discriminator—compete against each other in a minimax game. The generator $G(z)$ takes random noise $z$ as input and produces a data sample $G(z)$, while the discriminator $D(X)$ attempts to distinguish between real data samples and those generated by $G$.

The objective of the generator is to produce data that is indistinguishable from the real data, while the discriminator’s goal is to correctly classify real and generated data. This competition can be formalized by the following minimax optimization problem:

$$ \min_G \max_D \mathbb{E}_{X \sim P_{data}(X)} \left[ \log D(X) \right] + \mathbb{E}_{z \sim P_z(z)} \left[ \log(1 - D(G(z))) \right] $$

Here, $P_{data}$ is the true data distribution, and $P_z(z)$ is the distribution from which the generator samples its input noise. The generator improves by minimizing the discriminator’s ability to distinguish between real and generated samples, while the discriminator improves by maximizing its ability to make this distinction.

GANs have proven remarkably successful in generating high-quality images, videos, and audio. The adversarial framework enables GANs to produce realistic samples even when the data distribution is complex and high-dimensional. However, training GANs is notoriously difficult due to issues such as mode collapse (where the generator only produces a limited range of samples) and instability during training. Various techniques, such as Wasserstein GANs and conditional GANs, have been proposed to mitigate these challenges and improve the robustness of GAN training.

Generative models have broad applications in modern machine learning, ranging from image and speech generation to reinforcement learning and drug discovery. In image synthesis, for instance, GANs have been used to generate photorealistic images, create art, and perform style transfer. In natural language processing, VAEs and GANs have been applied to text generation, machine translation, and even generating novel dialogue in conversational agents. In reinforcement learning, generative models help in modeling environments and simulating potential scenarios, allowing agents to learn more efficiently.

Figure 5: Difference between GAN, VAE and Diffusion models. We focus on GAN and VAE only.

Moreover, generative models are essential for data augmentation, especially in scenarios where labeled data is scarce. By generating new samples from the learned distribution, these models can enhance the training set, thereby improving the performance of discriminative models. This synergy between generative and discriminative models underscores the importance of understanding generative modeling in the broader context of machine learning.

To illustrate the practical implementation of a generative model, we will focus on a simple Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) using Rust. The GMM will learn from a dataset and generate new data points that conform to the learned distribution. Rust's performance-oriented design and rich ecosystem make it a suitable option for developing such models. The implementation begins with defining a structure to represent the GMM, including the number of components (clusters), the means and covariances of the Gaussian distributions, and the mixing coefficients.

[dependencies]

rand = "0.8"

Here's a basic implementation of a GMM in Rust:

use rand::Rng;

use std::f64;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Gaussian {

mean: Vec<f64>,

covariance: Vec<Vec<f64>>,

}

#[derive(Debug)]

struct GMM {

components: Vec<Gaussian>,

weights: Vec<f64>,

}

impl GMM {

fn new(components: Vec<Gaussian>, weights: Vec<f64>) -> GMM {

GMM { components, weights }

}

fn pdf(&self, x: &Vec<f64>) -> f64 {

let mut total_prob = 0.0;

for (i, component) in self.components.iter().enumerate() {

let prob = self.weights[i] * self.gaussian_pdf(x, &component.mean, &component.covariance);

total_prob += prob;

}

total_prob

}

fn gaussian_pdf(&self, x: &Vec<f64>, mean: &Vec<f64>, covariance: &Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> f64 {

let dim = x.len() as f64;

let det = self.determinant(covariance);

let norm_const = 1.0 / ((2.0 * f64::consts::PI).powf(dim / 2.0) * det.sqrt());

let diff = self.subtract_vec(x, mean);

let exponent = -0.5 * self.quadratic_form(&diff, covariance);

norm_const * exponent.exp()

}

fn determinant(&self, matrix: &Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> f64 {

// Simple implementation for 2x2 matrix determinant

matrix[0][0] * matrix[1][1] - matrix[0][1] * matrix[1][0]

}

fn quadratic_form(&self, v: &Vec<f64>, matrix: &Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> f64 {

let mut result = 0.0;

for i in 0..v.len() {

for j in 0..v.len() {

result += v[i] * matrix[i][j] * v[j];

}

}

result

}

fn subtract_vec(&self, v1: &Vec<f64>, v2: &Vec<f64>) -> Vec<f64> {

v1.iter().zip(v2.iter()).map(|(a, b)| a - b).collect()

}

fn sample(&self) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let component_index = self.choose_component(&mut rng);

let component = &self.components[component_index];

let mut sample = Vec::new();

for i in 0..component.mean.len() {

let value = rng.gen::<f64>() * component.covariance[i][i].sqrt() + component.mean[i];

sample.push(value);

}

sample

}

fn choose_component(&self, rng: &mut dyn rand::RngCore) -> usize {

let mut cumulative_weights = Vec::new();

let mut sum = 0.0;

for weight in &self.weights {

sum += weight;

cumulative_weights.push(sum);

}

let sample: f64 = rng.gen_range(0.0..sum);

cumulative_weights.iter().position(|&x| x > sample).unwrap()

}

}

fn main() {

let gmm = GMM::new(

vec![

Gaussian { mean: vec![0.0, 0.0], covariance: vec![vec![1.0, 0.0], vec![0.0, 1.0]] },

Gaussian { mean: vec![5.0, 5.0], covariance: vec![vec![1.0, 0.0], vec![0.0, 1.0]] },

],

vec![0.5, 0.5],

);

let sample = gmm.sample();

println!("Generated sample: {:?}", sample);

}

In this code, we create a basic structure for the GMM, including methods for calculating the probability density functions and generating samples. The sample method randomly selects a component based on the weights and generates a new data point from the corresponding Gaussian distribution. The mathematical operations required for Gaussian probability density function calculation, such as determinant and quadratic forms, are also implemented.

In conclusion, generative models are indispensable tools in machine learning, enabling a range of applications from data synthesis to anomaly detection. By understanding the core principles and implementing a simple model such as a Gaussian Mixture Model in Rust, practitioners can begin to explore the vast potential of generative modeling in their projects. This foundational understanding sets the stage for delving into more complex models and their applications in real-world scenarios.

12.5. Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM)

Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) are a class of probabilistic models designed to represent complex data distributions by modeling the data as arising from a mixture of several Gaussian distributions. Each component Gaussian in the mixture is defined by its own mean vector and covariance matrix, making GMMs highly flexible and capable of capturing data that may come from multiple underlying sources or clusters. GMMs are particularly useful in various applications, including clustering, density estimation, and anomaly detection, where the goal is to model or infer the underlying distribution of the data, even when it may not adhere to a single Gaussian form.

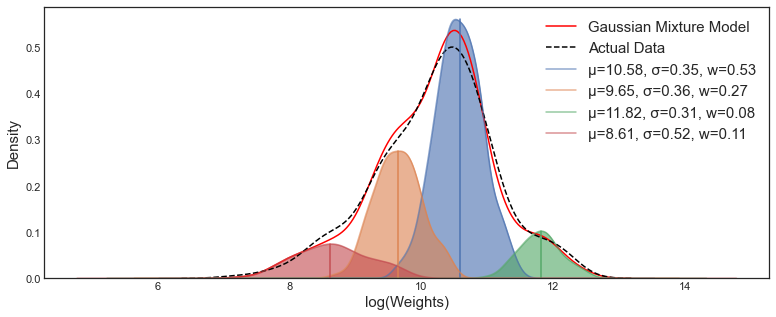

Figure 6: Example of GMM analysis.

Mathematically, a GMM assumes that the data points are generated from a mixture of kkk different Gaussian distributions. The probability density function (PDF) for a GMM is given by:

$$ P(x) = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \pi_i \mathcal{N}(x \mid \mu_i, \Sigma_i) $$

where $k$ is the number of Gaussian components, $\pi_i$ is the weight or mixing coefficient of the $i$-th component (such that $\sum_{i=1}^{k} \pi_i = 1$), $\mu_i$ is the mean vector of the iii-th Gaussian component, $\Sigma_i$ is the covariance matrix of the $i$-th component, and $\mathcal{N}(x \mid \mu_i, \Sigma_i)$ is the multivariate Gaussian distribution defined by:

$$ \mathcal{N}(x \mid \mu, \Sigma) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{d/2} |\Sigma|^{1/2}} \exp \left( -\frac{1}{2}(x - \mu)^\top \Sigma^{-1} (x - \mu) \right) $$

Here, $d$ is the dimensionality of the data, and $|\Sigma|$ denotes the determinant of the covariance matrix $\Sigma$.

The primary task in using GMMs is to estimate the parameters $\theta = \{ \pi_i, \mu_i, \Sigma_i \}_{i=1}^{k}$, which consist of the mixing coefficients, means, and covariances of the Gaussian components. To estimate these parameters from a given dataset $\{ x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n \}$, we employ the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm. The EM algorithm is particularly well-suited for GMMs because it allows for the efficient computation of the maximum likelihood estimates (MLE) of the parameters, even when the data comes from a mixture of distributions with latent or hidden variables.

The EM algorithm is an iterative method for finding the maximum likelihood estimates of parameters in models with latent variables. In the case of GMMs, the latent variables correspond to the unknown component memberships of each data point. That is, for each data point $x_i$, we do not know from which Gaussian component it was generated. The EM algorithm alternates between estimating the component memberships (the Expectation step, or E-step) and updating the parameters of the Gaussian components based on these estimates (the Maximization step, or M-step).

Step 1: Initialization

Before running the EM algorithm, we initialize the parameters $\theta^{(0)} = \{ \pi_i^{(0)}, \mu_i^{(0)}, \Sigma_i^{(0)} \}$ for each Gaussian component, typically through random assignment or a method like $k$-means clustering.

Step 2: Expectation Step (E-step)

In the E-step, we compute the expected value of the latent variables, which, in the case of GMMs, are the posterior probabilities that a given data point $x_i$ was generated by the $j$-th Gaussian component. This probability, denoted by $\gamma_{ij}$, is calculated using Bayes' theorem:

$$ \gamma_{ij} = P(z_i = j \mid x_i, \theta^{(t)}) = \frac{\pi_j^{(t)} \mathcal{N}(x_i \mid \mu_j^{(t)}, \Sigma_j^{(t)})}{\sum_{l=1}^{k} \pi_l^{(t)} \mathcal{N}(x_i \mid \mu_l^{(t)}, \Sigma_l^{(t)})} $$

Here, $z_i$ is the latent variable indicating the component membership of $x_i$, and $\gamma_{ij}$ represents the responsibility that component $j$ takes for explaining data point $x_i$. The responsibilities $\gamma_{ij}$ are interpreted as the probabilities that each data point belongs to each Gaussian component.

Step 3: Maximization Step (M-step)

In the M-step, we update the parameters $\theta = \{ \pi_i, \mu_i, \Sigma_i \}$ to maximize the expected log-likelihood of the data, given the responsibilities computed in the E-step. The updated parameters are given by the following equations:

Updating the mixing coefficients: $\pi_j^{(t+1)} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \gamma_{ij}$

Updating the means: $\mu_j^{(t+1)} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \gamma_{ij} x_i}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \gamma_{ij}}$

Updating the covariances: $\Sigma_j^{(t+1)} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \gamma_{ij} (x_i - \mu_j^{(t+1)})(x_i - \mu_j^{(t+1)})^\top}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \gamma_{ij}}$

These updates ensure that the parameters are adjusted to maximize the likelihood of the observed data under the current model.

Step 4: Convergence

The E-step and M-step are repeated iteratively until the log-likelihood converges or changes by a small, predefined threshold between iterations. Convergence is typically measured by evaluating the log-likelihood function:

$$\log P(X \mid \theta) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log \left( \sum_{j=1}^{k} \pi_j \mathcal{N}(x_i \mid \mu_j, \Sigma_j) \right)$$

At convergence, the EM algorithm produces the maximum likelihood estimates of the parameters, providing a model that best fits the data in terms of Gaussian mixtures.

GMMs are widely used in various machine learning tasks. One common application is clustering, where GMMs can model complex, non-linear clusters more flexibly than methods like $k$-means, which assumes spherical clusters. In GMM-based clustering, data points are assigned to clusters based on the posterior probabilities $\gamma_{ij}$, which reflect the likelihood that a data point belongs to a given Gaussian component.

In density estimation, GMMs provide a flexible approach for modeling multimodal distributions. By combining multiple Gaussian components, GMMs can represent a wide range of data distributions, making them particularly useful when the data exhibits multiple peaks or clusters. GMMs are also employed in anomaly detection, where the probability of each data point is evaluated under the learned model. Points with very low probability are flagged as anomalies or outliers, as they are unlikely to have been generated by the same process as the majority of the data.

Implementing GMMs in Rust involves several steps, including initializing model parameters, performing the E-step and M-step, and iterating until convergence. Below is an example implementation of a simple GMM in Rust. In this implementation, we will utilize the ndarray crate for matrix operations and the ndarray-rand crate for generating random samples.

// Append Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

ndarray = "0.15.0"

ndarray-linalg = { version = "0.16.0", features = ["intel-mkl"] }

ndarray-rand = "0.14.0"

rand = "0.8.5"

First, we need to define a structure to hold our GMM parameters:

use ndarray::*;

use ndarray_linalg::{cholesky::*, Determinant, Inverse};

use ndarray_rand::rand_distr::Normal;

use ndarray_rand::RandomExt;

use rand::Rng;

struct Gaussian {

mean: Array1<f64>,

covariance: Array2<f64>,

}

struct GMM {

components: Vec<Gaussian>,

weights: Array1<f64>,

}

Next, we will implement the E-step of the EM algorithm. In this step, we compute the responsibilities for each data point based on the current parameters:

impl GMM {

fn e_step(&self, data: &Array2<f64>) -> Array2<f64> {

let n_samples = data.nrows();

let n_components = self.components.len();

let mut responsibilities = Array2::<f64>::zeros((n_samples, n_components));

for (i, sample) in data.axis_iter(Axis(0)).enumerate() {

let total_weighted_prob = self.components.iter().enumerate().map(|(j, component)| {

let prob = self.multivariate_gaussian(&sample.to_owned(), &component.mean, &component.covariance);

self.weights[j] * prob

}).sum::<f64>();

for j in 0..n_components {

let prob = self.multivariate_gaussian(&sample.to_owned(), &self.components[j].mean, &self.components[j].covariance);

responsibilities[[i, j]] = (self.weights[j] * prob) / total_weighted_prob;

}

}

responsibilities

}

fn multivariate_gaussian(&self, sample: &Array1<f64>, mean: &Array1<f64>, covariance: &Array2<f64>) -> f64 {

let d = mean.len();

let diff = sample - mean;

let det = covariance.det().expect("Matrix determinant could not be computed.");

if det == 0.0 {

panic!("Covariance matrix is singular.");

}

let inv_cov = covariance.inv().expect("Matrix is not invertible");

let exponent = -0.5 * diff.dot(&inv_cov.dot(&diff));

let coeff = 1.0 / ((2.0 * std::f64::consts::PI).powf(d as f64 / 2.0) * det.sqrt());

coeff * exponent.exp()

}

}

In the above code, we defined a method e_step that calculates the responsibilities for each data point. The multivariate_gaussian function computes the probability density of a point under a Gaussian distribution given its mean and covariance. The responsibilities matrix indicates how likely each data point belongs to each Gaussian component.

Next, we implement the M-step of the EM algorithm, where we update the parameters of our GMM:

impl GMM {

fn m_step(&mut self, data: &Array2<f64>, responsibilities: &Array2<f64>) {

let n_samples = data.nrows();

let n_components = self.components.len();

let d = data.ncols();

for j in 0..n_components {

let weight_sum = responsibilities.column(j).sum();

self.weights[j] = weight_sum / n_samples as f64;

let mean = data.t().dot(&responsibilities.column(j)) / weight_sum;

self.components[j].mean.assign(&mean);

let mut covariance = Array2::<f64>::zeros((d, d));

for i in 0..n_samples {

let diff = &data.row(i) - &self.components[j].mean;

covariance += responsibilities[[i, j]] * diff.t().dot(&diff);

}

self.components[j].covariance = covariance / weight_sum;

}

}

}

In the m_step function, we update the weights, means, and covariances of each Gaussian component. The weights are computed as the sum of responsibilities, while the means are updated based on the weighted sum of data points. The covariance is updated by accumulating the outer products of the differences between the data points and the means, weighted by the responsibilities.

Finally, we can create a method to fit our GMM to the data using the EM algorithm:

impl GMM {

fn fit(&mut self, data: &Array2<f64>, n_iterations: usize) {

for _ in 0..n_iterations {

let responsibilities = self.e_step(data);

self.m_step(data, &responsibilities);

}

}

}

This fit method runs the EM algorithm for a specified number of iterations, allowing the model to converge on optimal parameters.

In practice, GMMs can be applied to cluster data, where each Gaussian component represents a distinct cluster. Once the GMM is fitted to the data, we can also generate new data points from the learned mixture model. This is accomplished by sampling from the Gaussian components according to their respective weights.

The following code illustrates how to generate new samples from the fitted GMM:

impl GMM {

fn sample(&self, n_samples: usize) -> Array2<f64> {

let mut samples = Array2::<f64>::zeros((n_samples, self.components[0].mean.len()));

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for i in 0..n_samples {

// Generate a sample from one of the components

let component_index = rng.gen_range(0..self.components.len());

// Call the sample method with the number of samples (1 in this case)

let sample = self.components[component_index].sample(1, &mut rng);

samples.row_mut(i).assign(&sample);

}

samples

}

}

impl Gaussian {

fn sample(&self, n_samples: usize, rng: &mut impl Rng) -> Array2<f64> {

let normal = Normal::new(0.0, 1.0).unwrap();

let z = Array2::<f64>::random_using((n_samples, self.mean.len()), normal, rng);

let cholesky = self.covariance.cholesky(UPLO::Lower).expect("Matrix is not positive definite");

let samples = z + self.mean.view().insert_axis(Axis(0));

samples.dot(&cholesky)

}

}

In the sample method, we randomly choose which Gaussian component to sample from based on the mixture weights. Then we generate samples from the chosen Gaussian distribution, which involves transforming a standard normal sample using the Cholesky decomposition of the covariance matrix.

In conclusion, Gaussian Mixture Models are a versatile and widely used approach for modeling complex data distributions. By leveraging the EM algorithm, we can effectively estimate the parameters of the model, allowing us to perform clustering and generate new data points from the learned mixture model. The implementation in Rust showcases the use of matrix operations for efficient computation, and the modular structure of the code allows for further enhancements and extensions. As we continue to explore density estimation and generative models, GMMs serve as foundational tools in our machine learning toolkit.

12.6. Variational Autoencoders (VAE)

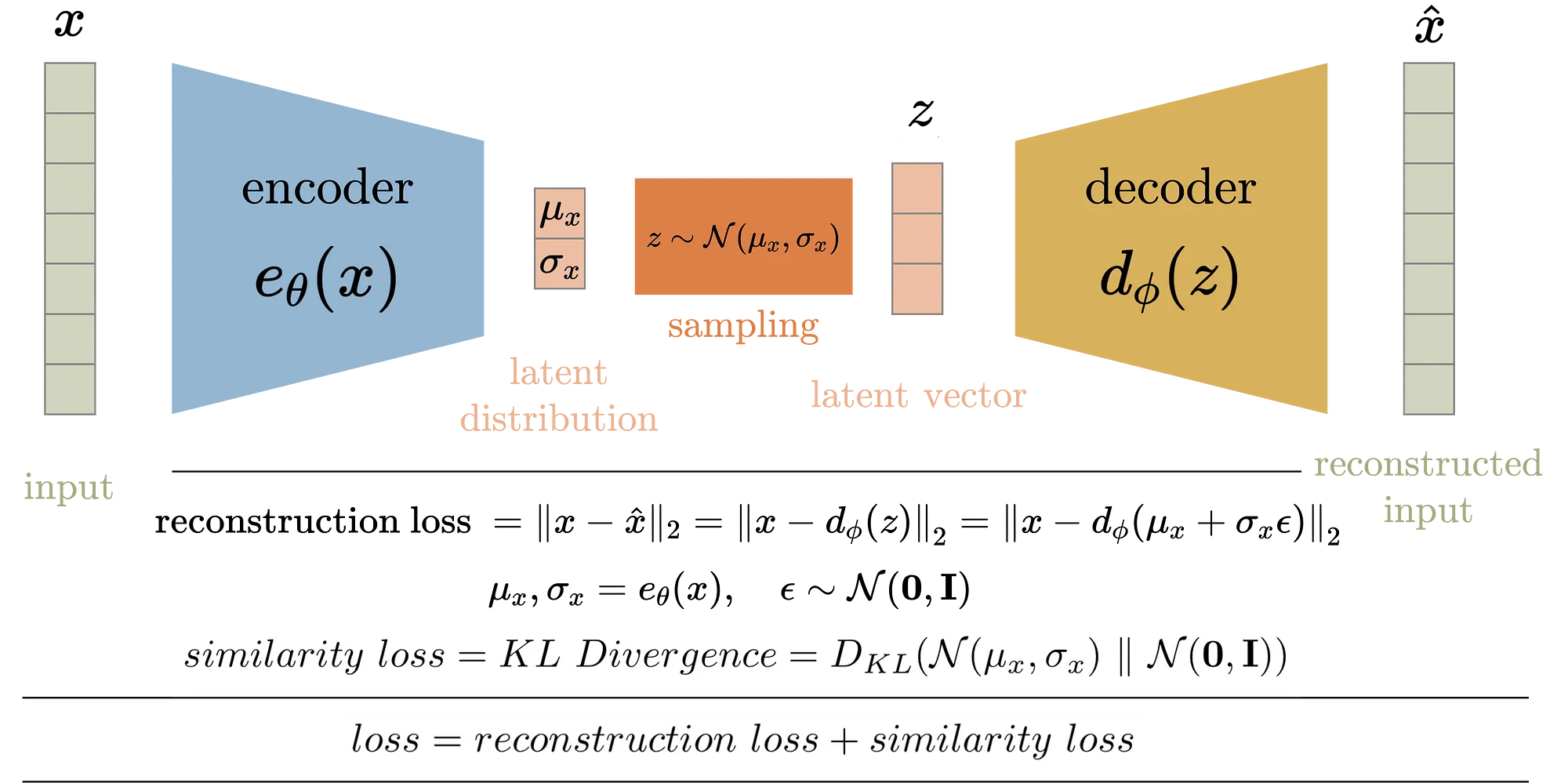

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) represent a significant advancement in generative modeling, combining the power of neural networks with probabilistic inference to create a flexible and scalable framework for learning latent representations of complex datasets. At the core of VAEs is the ability to encode high-dimensional input data into a lower-dimensional latent space and then decode this latent representation back into the original data space. This structure enables not only efficient data compression but also the generation of new data points that resemble the original data distribution, making VAEs a powerful tool for tasks such as data generation, anomaly detection, and unsupervised learning.

Figure 7: Variational Autoencoder (VAE) model architecture.

A VAE consists of three main components: the encoder, the decoder, and the latent space. The encoder network, often referred to as the recognition or inference model, takes an input data point $x \in \mathbb{R}^d$ and maps it into a distribution over the latent space $z \in \mathbb{R}^l$, where $l \ll d$. This mapping is probabilistic, typically parameterized as a multivariate Gaussian distribution with a mean vector $\mu(x)$ and a diagonal covariance matrix defined by the standard deviation $\sigma(x)$. The encoder thus learns the parameters $\mu(x)$ and $\sigma(x)$ that characterize the distribution $q(z \mid x)$, which approximates the true posterior distribution of the latent variables given the data.

The decoder network, also known as the generative model, takes a sample $z$ from the latent space and attempts to reconstruct the original data point $x$. The decoder is typically modeled as a conditional distribution $p(x \mid z)$, which defines the likelihood of the data given the latent variable. The goal of the decoder is to maximize the likelihood of the data given the latent representation, effectively learning how to generate realistic data points from the latent space.

The latent space serves as a compressed representation of the data, capturing the most salient features of the input. One of the key advantages of the VAE framework is that the latent space is continuous and structured, allowing for smooth interpolation between data points and enabling the generation of new samples by sampling from the latent distribution.

A central challenge in VAEs, as with many probabilistic models, is the need to perform inference over latent variables. In particular, we are interested in computing the posterior distribution $p(z \mid x)$, which captures the distribution of the latent variable $z$ given the observed data $x$. However, directly computing this posterior is intractable due to the complex nature of the integrals involved in Bayesian inference.

To address this issue, VAEs employ variational inference, a method that approximates the true posterior $p(z \mid x)$ with a simpler, tractable distribution $q(z \mid x)$. This approximate posterior is chosen from a family of distributions (typically Gaussian) that is easy to sample from and manipulate. The goal is to make the approximate posterior $q(z \mid x)$ as close as possible to the true posterior $p(z \mid x)$, which is measured using Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence:

$$ D_{KL} \left( q(z \mid x) \parallel p(z \mid x) \right) = \mathbb{E}_{q(z \mid x)} \left[ \log \frac{q(z \mid x)}{p(z \mid x)} \right] $$

The VAE optimizes a lower bound on the log-likelihood of the observed data, known as the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO). The ELBO is the objective function that the VAE seeks to maximize, and it can be expressed as:

$$ \log p(x) \geq \mathbb{E}_{q(z \mid x)} \left[ \log p(x \mid z) \right] - D_{KL} \left( q(z \mid x) \parallel p(z) \right) $$

Here, the first term, $\mathbb{E}_{q(z \mid x)} \left[ \log p(x \mid z) \right]$, is the reconstruction loss, which measures how well the decoder can reconstruct the original data from the latent variables. This term encourages the model to accurately regenerate the input data from the latent representation, thereby ensuring that the latent space captures the most important features of the data.

The second term, $D_{KL} \left( q(z \mid x) \parallel p(z) \right)$, is a regularization term that penalizes the difference between the approximate posterior $q(z \mid x)$ and the prior distribution $p(z)$, typically chosen to be a standard Gaussian $\mathcal{N}(0, I)$. This regularization ensures that the latent space remains structured and prevents the model from overfitting by constraining the learned latent representations to follow a smooth, continuous distribution. By balancing these two terms, the VAE learns a latent space that is both informative and well-behaved for sampling.

A key innovation in the VAE framework is the reparameterization trick, which allows for efficient backpropagation through the stochastic latent variables. Normally, the sampling process would introduce non-differentiable randomness, making it impossible to compute gradients with respect to the parameters of the model. However, the reparameterization trick overcomes this issue by expressing the sampled latent variable $z$ as a deterministic function of the mean $)\mu(x)$ and standard deviation $\sigma(x)$, plus some random noise ϵ\\epsilonϵ drawn from a standard normal distribution:

$$ z = \mu(x) + \sigma(x) \cdot \epsilon \quad \text{where} \quad \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I) $$

This formulation allows the gradients to be propagated through the mean and variance parameters of the encoder, enabling the VAE to be trained using standard gradient-based optimization techniques such as stochastic gradient descent.

The training of a VAE involves maximizing the ELBO with respect to the parameters of both the encoder and decoder networks. This is typically done using stochastic gradient descent, where the gradients are computed with respect to both the reconstruction loss and the KL divergence regularization term. The encoder learns to map the input data into a latent space that captures the underlying structure of the data, while the decoder learns to map points from this latent space back to the data space in a way that maximizes the likelihood of the observed data.

The result is a powerful generative model that can not only generate realistic samples from the learned distribution but also capture meaningful latent representations that can be used for tasks such as clustering, dimensionality reduction, and data augmentation.

VAEs have proven to be highly effective in a range of applications, particularly in fields where generating new data or learning compressed representations is important. In image generation, for example, VAEs have been used to generate realistic images by sampling from the latent space and decoding these samples back into the image space. This has applications in areas such as art generation, image inpainting, and style transfer.

In the context of natural language processing, VAEs have been applied to text generation, where the model learns a latent representation of sentences or documents, allowing for the generation of novel text. VAEs are also used in reinforcement learning, where they help model the latent structure of complex environments, facilitating more efficient exploration and decision-making by learning compact representations of high-dimensional state spaces.

In this chapter, we will delve into the implementation of VAEs using Rust, focusing on efficiently encoding and decoding complex datasets. The Rust implementation will leverage high-performance neural network libraries to train VAEs and explore practical applications in areas such as image generation and anomaly detection. By providing detailed theoretical insights and practical coding examples, this chapter will offer a comprehensive guide to using VAEs for generative modeling and latent space learning in Rust.

To implement a Variational Autoencoder in Rust, we can utilize the tch-rs library, which provides bindings for the PyTorch C++ library, allowing us to leverage the power of deep learning directly in Rust. Below is an example of how one might go about implementing a VAE, applying it to the MNIST dataset, and generating new samples from the learned latent space.

First, we need to set up our dependencies in the Cargo.toml file. The tch crate will allow us to work with tensors and neural networks effectively:

[dependencies]

ndarray = "0.15.0"

tch = "0.17.0"

Next, we can proceed to define our VAE structure, which includes the encoder and decoder networks. Here is a simplified implementation:

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, Device, Tensor};

#[derive(Debug)]

struct VAE {

encoder: nn::Sequential,

decoder: nn::Sequential,

latent_dim: i64,

}

impl VAE {

fn new(vs: &nn::Path, latent_dim: i64) -> VAE {

let encoder = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "encoder1", 784, 400, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "mu", 400, latent_dim, Default::default()))

.add(nn::linear(vs / "logvar", 400, latent_dim, Default::default()));

let decoder = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "decoder1", latent_dim, 400, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "output", 400, 784, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.sigmoid());

VAE { encoder, decoder, latent_dim }

}

fn encode(&self, x: &Tensor) -> (Tensor, Tensor) {

let output = self.encoder.forward(x); // Forward pass through the encoder

let split_output = output.split(self.latent_dim, 1); // Split the output into a Vec<Tensor>

let mu = split_output[0].copy(); // First element is mu

let logvar = split_output[1].copy(); // Second element is logvar

(mu, logvar)

}

fn reparameterize(&self, mu: &Tensor, logvar: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let std = logvar.multiply_scalar(0.5).exp();

let eps = Tensor::randn(&std.size(), (std.kind(), std.device()));

&eps * &std + mu

}

fn decode(&self, z: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

self.decoder.forward(z)

}

fn forward(&self, x: &Tensor) -> (Tensor, Tensor, Tensor) {

let (mu, logvar) = self.encode(x);

let z = self.reparameterize(&mu, &logvar);

let recon_x = self.decode(&z);

(recon_x, mu, logvar)

}

fn loss(&self, recon_x: &Tensor, x: &Tensor, mu: &Tensor, logvar: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let recon_loss = (x - recon_x).pow_tensor_scalar(2).sum(tch::Kind::Float).mean(tch::Kind::Float);

let one = Tensor::ones(&logvar.size(), (tch::Kind::Float, logvar.device()));

let kl_div = -0.5 * (one + logvar - mu.pow_tensor_scalar(2) - logvar.exp())

.sum(tch::Kind::Float)

.mean(tch::Kind::Float);

recon_loss + kl_div

}

}

In the above code, we define a VAE struct that contains the encoder and decoder networks. The encode method computes the mean and log variance of the latent space representation, while the reparameterize method samples from this distribution to ensure that the gradients can flow during training. The decode method reconstructs the input from the latent representation. The forward method combines these steps, and the loss method computes the total loss, which includes both the reconstruction loss and the KL divergence.

To train our VAE, we need to load the MNIST dataset, process it, and then run the training loop. For simplicity, we assume the dataset has been preprocessed and is available as train_loader.

fn train_vae(vae: &VAE, train_loader: &DataLoader, optimizer: &mut nn::Optimizer) {

for (images, _) in train_loader {

let images = images.view([-1, 784]).to(Device::cuda_if_available());

optimizer.zero_grad();

let (recon_images, mu, logvar) = vae.forward(&images);

let loss = vae.loss(&recon_images, &images, &mu, &logvar);

loss.backward();

optimizer.step();

}

}

In the training function, we iterate over the batches of the dataset. For each batch, we compute the forward pass, calculate the loss, and then perform backpropagation to update the model parameters.

Finally, after training the VAE, we can generate new samples by sampling points from the latent space and passing them through the decoder:

fn sample_latent_and_generate(vae: &VAE) -> Tensor {

let z = Tensor::randn(&[1, vae.latent_dim], (tch::Kind::Float, Device::cuda_if_available()));

vae.decode(&z)

}

This function samples from a standard normal distribution in the latent space and generates a new sample using the decoder network.

In summary, Variational Autoencoders provide a robust framework for learning latent representations and generating new data. By understanding the roles of the encoder, decoder, and the implications of variational inference, one can effectively implement and utilize VAEs in Rust. The combination of these concepts allows for powerful applications in generating new, high-dimensional data points that reflect the underlying distribution of the training dataset.

12.7. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

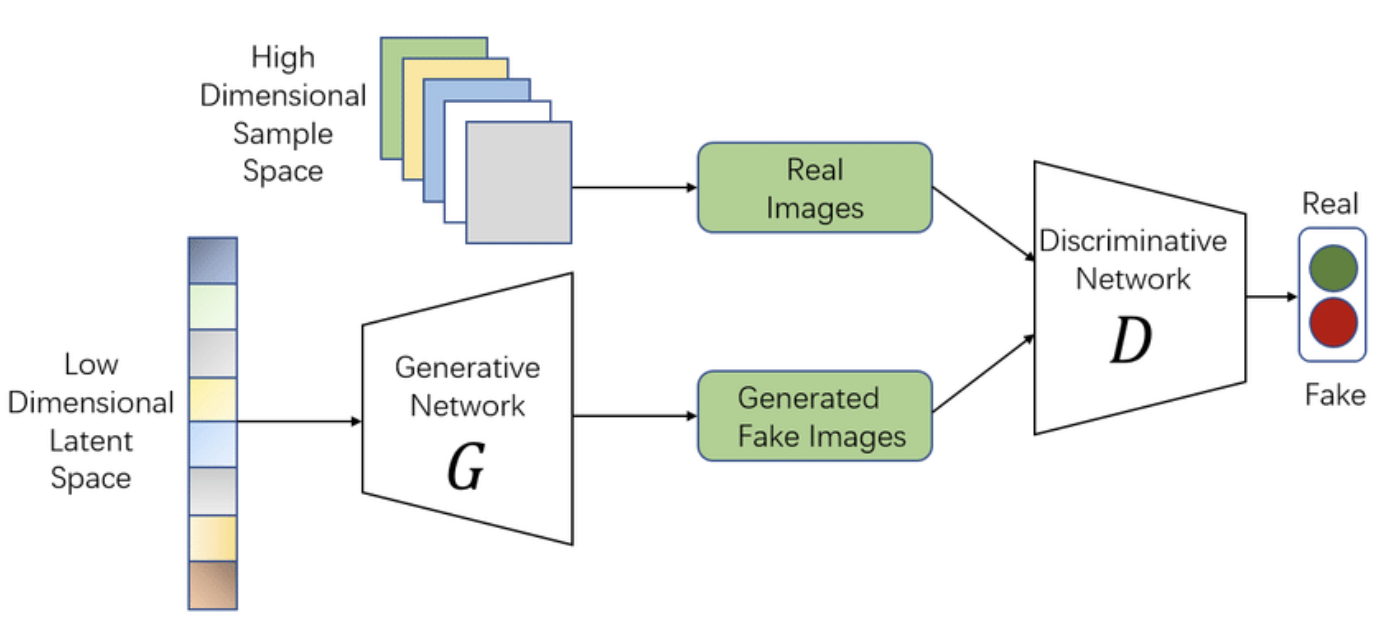

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have introduced a novel approach to generative modeling by establishing an adversarial dynamic between two neural networks: the generator and the discriminator. This interaction creates a powerful framework where the generator learns to produce data samples that are indistinguishable from real data, while the discriminator attempts to differentiate between genuine data points and those generated by the generator. The adversarial process enables GANs to learn the underlying distribution of complex datasets and generate highly realistic synthetic data. This capability has broad applications in areas such as image synthesis, video generation, and data augmentation.

Figure 8: The architecture of Vanilla GAN.

At the core of a GAN are two neural networks that engage in a minimax game:

The generator $G(z)$, which takes a random input $z$ drawn from a prior distribution $p_z(z)$ (usually a standard normal distribution) and maps it to the data space. The generator’s goal is to transform this noise into a synthetic data point $G(z)$ that resembles a sample from the true data distribution $p_{data}(x)$. The generator is trained to "fool" the discriminator into classifying its outputs as real data.

The discriminator $D(x)$ acts as a binary classifier. It receives samples from both the true data distribution and the generator’s output, and its objective is to correctly distinguish between real samples and fake ones produced by the generator. The discriminator outputs a probability $D(x) \in [0, 1]$, where $D(x)$represents the probability that $x$ is a real data point.

The interaction between these two networks is captured by the minimax objective function:

$$ \min_G \max_D \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{data}(x)} \left[ \log D(x) \right] + \mathbb{E}_{z \sim p_z(z)} \left[ \log(1 - D(G(z))) \right] $$

This formulation represents the following two goals:

The discriminator $D(x)$ aims to maximize its ability to correctly classify real data from fake data generated by $G(z)$. The first term $\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{data}(x)} \left[ \log D(x) \right]$ increases when $D(x)$ correctly classifies real data, and the second term $\mathbb{E}_{z \sim p_z(z)} \left[ \log(1 - D(G(z))) \right]$ increases when $D(x)$ correctly identifies the generator’s outputs as fake.

The generator $G(z)$, on the other hand, minimizes this objective by trying to reduce $\log(1 - D(G(z)))$, forcing the discriminator to classify the generated data as real.

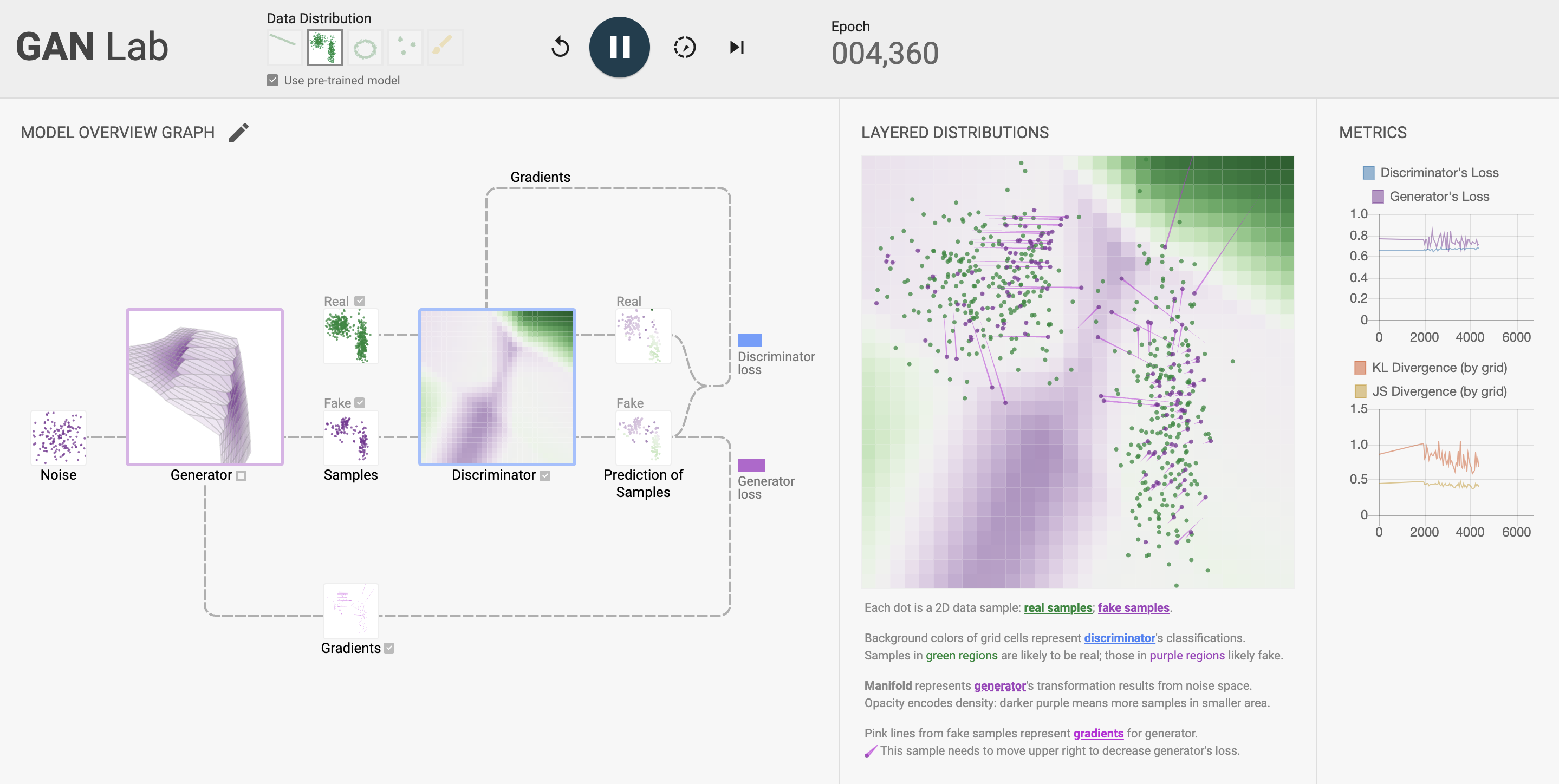

The training process of GANs is inherently adversarial, with the generator and discriminator continuously improving in response to each other. Initially, the generator's outputs may be easily distinguished by the discriminator. Over time, as the generator improves, its outputs become more realistic, and the discriminator must adapt to maintain its accuracy in distinguishing real from fake data.

The training alternates between optimizing the discriminator and the generator. First, the discriminator is updated by maximizing the log-likelihood of correctly classifying real and generated data. Then, the generator is updated to minimize the log-likelihood that the discriminator correctly identifies its outputs as fake. The adversarial nature of the training process ensures that both networks improve over time.

Figure 9: Illustrated GAN training dynamic (GANLab, https://poloclub.github.io/ganlab/).

Formally, the training procedure can be described as follows:

Discriminator Update: Given a batch of real data points $x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n$ from the dataset, and a batch of generated data points $G(z_1), G(z_2), \dots, G(z_n)$, where $z_i \sim p_z(z)$ are random noise samples, the discriminator’s parameters are updated by maximizing the following loss:

$$L_D = - \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[ \log D(x_i) + \log(1 - D(G(z_i))) \right]$$

-Generator Update: The generator’s parameters are updated by minimizing the following loss, which seeks to fool the discriminator into classifying generated samples as real:

$$ L_G = - \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log D(G(z_i)) $$

The minimax game continues until equilibrium is reached, where the generator produces samples that the discriminator is unable to reliably distinguish from real data. Ideally, at this point, $D(x) \approx \frac{1}{2}$ for both real and generated data, indicating that the discriminator is no better than random guessing.

While the GAN framework is theoretically elegant, training GANs presents several practical challenges. One of the most common issues is mode collapse, where the generator produces a limited variety of outputs, effectively ignoring some modes of true data distribution. In this scenario, the generator finds a narrow subset of outputs that consistently fool the discriminator, leading to the generation of highly similar samples while ignoring the diversity present in the real data.

Mode collapse occurs because the generator is incentivized to exploit weaknesses in the discriminator’s classification. Once the generator finds a small set of outputs that can fool the discriminator, it may not explore other regions of the data distribution. This results in a lack of diversity in the generated samples, which is problematic for tasks where a wide variety of outputs is essential.

Another significant challenge is training instability. The adversarial nature of GANs can lead to oscillations in the loss values of both the generator and discriminator, making it difficult for the model to converge. This instability arises from the fact that the optimization problem is non-convex and the gradient updates of the generator and discriminator can interfere with each other, leading to unpredictable behavior during training.

Several techniques have been proposed to mitigate mode collapse and stabilize the training of GANs. One common approach is to modify the loss function. Instead of using the standard binary cross-entropy loss, practitioners often employ alternative loss functions, such as the Wasserstein distance (used in Wasserstein GANs) that provides smoother gradients and leads to more stable training dynamics. The Wasserstein GAN objective is formulated as:

$$ L_W = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p_{data}(x)} \left[ D(x) \right] - \mathbb{E}_{z \sim p_z(z)} \left[ D(G(z)) \right] $$

This formulation avoids vanishing gradients and encourages the generator to explore the entire data distribution rather than collapsing onto a narrow set of outputs.

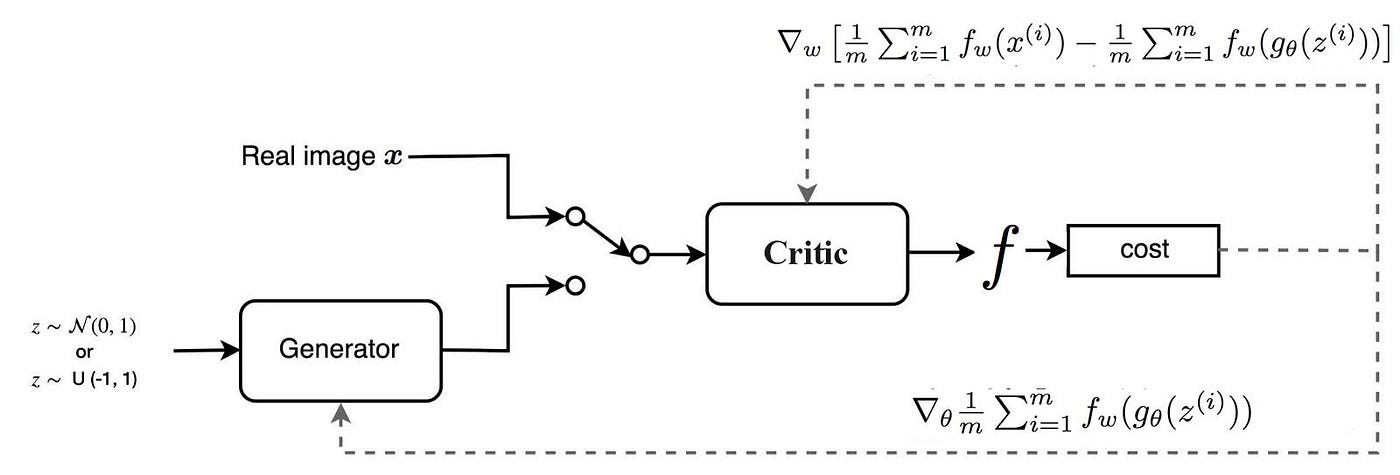

Figure 10: Wasserstein GAN (WGAN) model architecture.

Another approach to prevent mode collapse is to introduce regularization techniques, such as gradient penalties or instance noise, which help to smooth out the training process by preventing the generator and discriminator from becoming too confident in their classifications.

In addition, researchers have experimented with architectural modifications to the generator and discriminator networks. For example, increasing the capacity of the networks or introducing additional layers of complexity can improve the models' ability to capture the intricacies of the data distribution.

GANs have revolutionized several areas of machine learning, particularly in tasks related to image synthesis. They are capable of generating highly realistic images, enabling applications such as super-resolution, image inpainting, and style transfer. GANs have also been used in video generation, where they generate continuous video frames, and in text-to-image synthesis, where GANs generate images that correspond to specific textual descriptions.

Beyond image generation, GANs are employed in data augmentation, where they generate additional training examples to improve the performance of discriminative models. GANs are also used in anomaly detection, where the discriminator is trained to detect unusual or rare patterns in data.

In this chapter, we will explore the implementation of GANs in Rust, focusing on how to efficiently train both the generator and discriminator networks. By leveraging Rust’s performance and memory safety features, we will build scalable and robust GAN implementations that can be applied to a variety of tasks, including image generation and data augmentation. Through a combination of theoretical foundations and practical coding examples, readers will gain a deep understanding of how to apply GANs to real-world machine learning problems.

To illustrate the implementation of a GAN in Rust, we can utilize the ndarray and tch crates for numerical operations and tensor manipulations, respectively. Below is a simplified example of how to set up a GAN framework in Rust, focusing on generating synthetic data.

First, we define the generator and discriminator models. For simplicity, we will use fully connected layers:

use ndarray;

use tch;

use ndarray::Array2;

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Tensor};

// Define the generator

fn generator(vs: &nn::Path) -> impl nn::Module {

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs, 100, 256, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs, 256, 512, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs, 512, 784, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.tanh())

}