Chapter 14

Reinforcement Learning

"Learning is not attained by chance, it must be sought for with ardor and diligence." — Abigail Adams

Chapter 14 of MLVR offers a comprehensive exploration of Reinforcement Learning (RL), a foundational area of machine learning where agents learn to make decisions by interacting with their environment. The chapter begins with an introduction to the core concepts of RL, including agents, environments, and the reward-driven learning process. It then delves into key mathematical frameworks like Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) and dynamic programming techniques for solving RL problems. The chapter also covers essential RL methods such as Monte Carlo, temporal-difference learning, and function approximation, providing practical examples of their implementation in Rust. Advanced topics like deep reinforcement learning and policy gradient methods are explored, highlighting their potential in solving complex real-world problems. Finally, the chapter emphasizes the importance of evaluating and tuning RL algorithms, ensuring that readers can effectively apply these techniques to achieve optimal performance.

14.1 Introduction to Reinforcement Learning

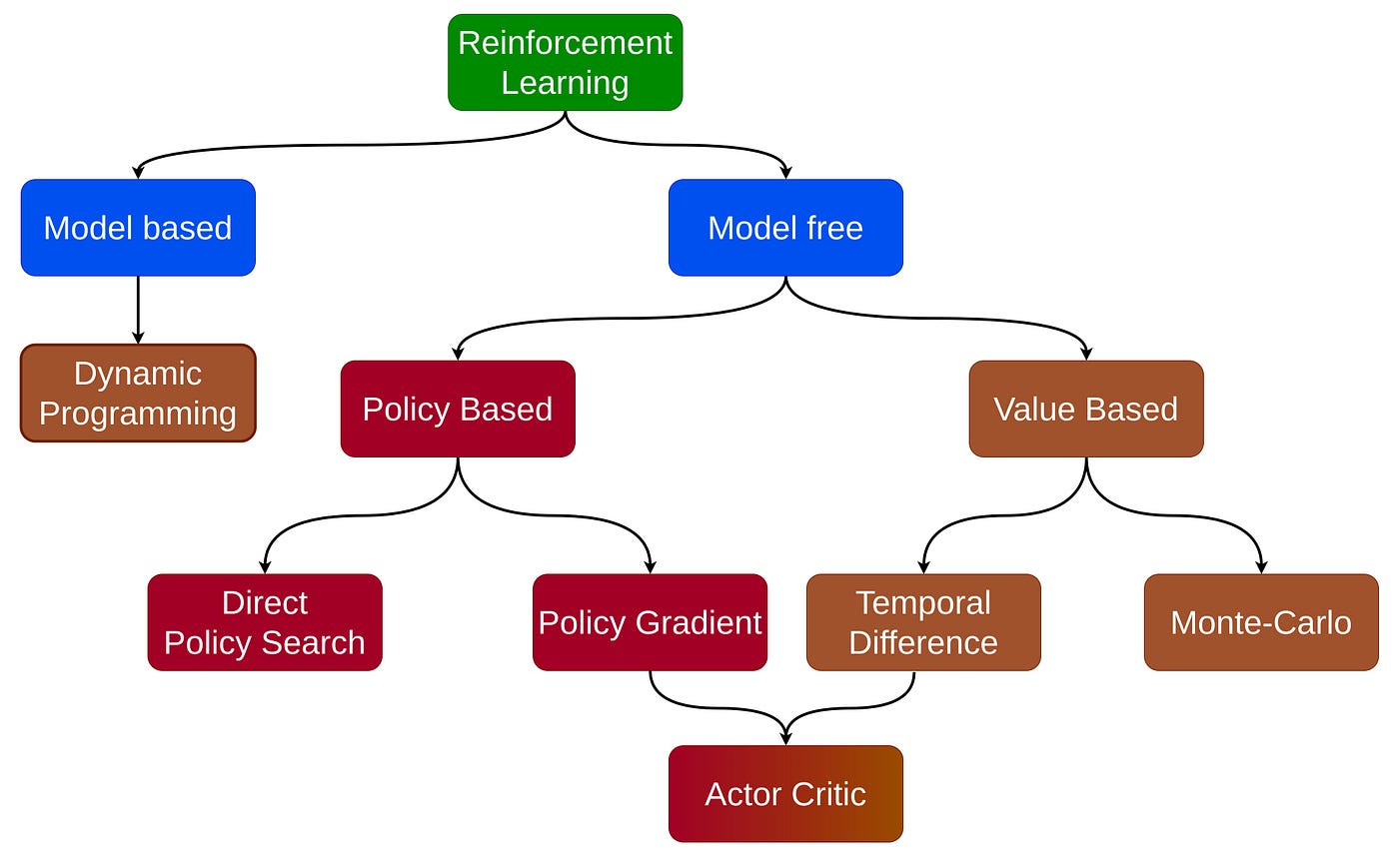

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a foundational area of machine learning that focuses on how an agent can learn to make optimal decisions through interactions with its environment, with the objective of maximizing cumulative rewards. In contrast to supervised learning, where the agent is provided with explicit labels for correct actions, reinforcement learning operates in a framework where the agent must learn through trial and error by observing the outcomes of its actions. This interaction is formalized through a feedback mechanism where the agent receives rewards (or penalties) from the environment based on the actions it takes, and the goal is to develop a policy that maximizes the expected cumulative reward over time. Reinforcement learning (RL) can be broadly classified into two main categories based on how the agent interacts with the environment and learns to make decisions: model-based and model-free approaches.

Model-free reinforcement learning is the approach where the agent has no prior knowledge about the environment's dynamics. In this case, the agent must learn how to act solely through trial and error by interacting with the environment, observing the rewards, and adapting its actions accordingly. This method is advantageous in situations where the environment is complex, and modeling the transitions explicitly would be too difficult or computationally expensive. In model-free approaches, the agent either focuses on learning the value of actions or directly learns a policy.

In value-based methods, the agent aims to estimate the value of states or state-action pairs. The value function represents the expected cumulative reward the agent would receive from a given state or after taking a particular action. Once the agent learns the value function, it can decide what action to take in each state by choosing the action that maximizes future rewards. An example of this method is Q-learning, where the agent iteratively updates its estimate of the expected reward for each action based on the rewards it receives and its estimate of future rewards. Deep Q-Networks (DQN), an extension of Q-learning, uses neural networks to approximate the value function, enabling the agent to operate in environments with very large or continuous state spaces.

On the other hand, in policy-based methods, the agent directly learns a policy, which is a mapping from states to actions. Rather than estimating the value of actions, the agent focuses on learning which actions are best to take in each state. This can be beneficial in environments where the optimal policy may not necessarily involve deterministic decisions but instead requires probabilistic strategies. Policy-based methods often use gradient-based techniques to improve the policy by maximizing the expected cumulative reward. One such approach is the REINFORCE algorithm, where the agent updates the policy parameters based on the rewards it receives, aiming to make better decisions over time.

Model-based reinforcement learning is fundamentally different in that the agent actively builds or uses a model of the environment's dynamics. In this case, the agent learns or is given a model that describes how the environment responds to its actions, including the probabilities of transitioning between states and the rewards associated with those transitions. Using this model, the agent can plan ahead, simulate future interactions with the environment, and determine the best actions to take. This allows for more efficient learning because the agent can anticipate the outcomes of its actions without needing to rely solely on direct experience. Model-based approaches are useful when it is possible to construct or learn an accurate model of the environment and when planning and simulation can lead to better decision-making.

Figure 1: Taxonomy of Reinforcement Learning model.

The key distinction between model-based and model-free approaches lies in the availability of information about the environment. Model-based approaches require an understanding of how the environment behaves, which can be learned or provided, allowing the agent to plan ahead. Model-free approaches, in contrast, rely only on the agent’s experiences and do not involve explicit modeling of the environment, making them more flexible but potentially slower to learn in certain settings. Both approaches have their own strengths and weaknesses, with model-free methods often excelling in large, complex environments where modeling is impractical, and model-based methods proving more efficient in environments where the agent can leverage a learned or known model to plan and make better decisions.

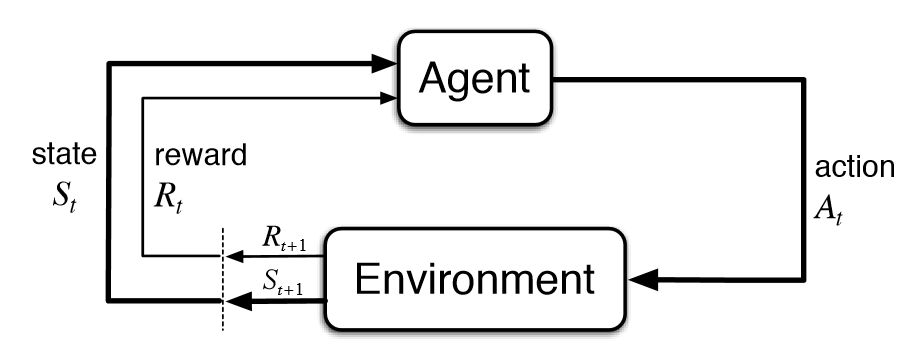

Formally, we can model reinforcement learning using the simple framework of a Markov Decision Process (MDP). An MDP is defined by a tuple $(S, A, P, R, \gamma)$, where $S$ is the set of states, $A$ is the set of actions, $P(s' \mid s, a)$ is the transition probability from state $s$ to state $s'$ given action a, $R(s, a)$ is the reward function that assigns a numerical reward when the agent takes action $a$ in state s, and $\gamma \in [0, 1]$ is the discount factor that reflects the trade-off between immediate and future rewards. The agent's goal is to learn a policy $\pi(a \mid s)$, which is a mapping from states to a probability distribution over actions, such that the expected cumulative reward, also known as the return, is maximized.

Figure 2: Reinforcement learning model.

The cumulative reward or return is defined as the sum of discounted future rewards:

$$ G_t = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k R_{t+k+1}, $$

where $G_t$ is the return starting from time $t$, and $\gamma^k$ is the discount applied to the reward received $k$-steps into the future. The discount factor $\gamma$ serves to weigh immediate rewards more heavily than distant future rewards, helping the agent focus on the short-term vs. long-term trade-off.

At the core of reinforcement learning are several key components: the agent, the environment, states, actions, and rewards. The agent observes the current state $s \in S$ of the environment and selects an action $a \in A$ according to its policy $\pi(a \mid s)$. The environment then transitions to a new state $s'$ according to the transition dynamics $P(s' \mid s, a)$ and provides the agent with a reward $R(s, a)$. The agent’s task is to optimize its policy $\pi$ to maximize the expected cumulative reward.

One of the main challenges in reinforcement learning is the exploration-exploitation trade-off. Exploration refers to the agent's attempt to discover new actions and states that may lead to higher rewards, while exploitation involves leveraging the current knowledge to select actions that are known to yield high rewards. Mathematically, this trade-off can be framed by considering the value function, which measures the expected return from a given state. The state-value function $V^\pi(s)$ under a policy $\pi$ is defined as:

$$ V^\pi(s) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ G_t \mid S_t = s \right] = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k R_{t+k+1} \mid S_t = s \right], $$

where the expectation is taken over the trajectory of states and actions following the policy $\pi$. Similarly, the action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$ represents the expected return when the agent takes action $a$ in state $s$ and then follows policy $\pi$:

$$ Q^\pi(s, a) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ G_t \mid S_t = s, A_t = a \right]. $$

Learning a good policy involves estimating these value functions to determine which actions yield the highest expected rewards. A key family of algorithms in reinforcement learning is based on dynamic programming, which leverages the Bellman equations to iteratively improve estimates of the value functions. The Bellman equation for the state-value function is given by:

$$ V^\pi(s) = \sum_{a \in A} \pi(a \mid s) \left[ R(s, a) + \gamma \sum_{s'} P(s' \mid s, a) V^\pi(s') \right], $$

which expresses the value of a state as the expected immediate reward plus the discounted value of the next state, averaged over all possible actions and transitions.

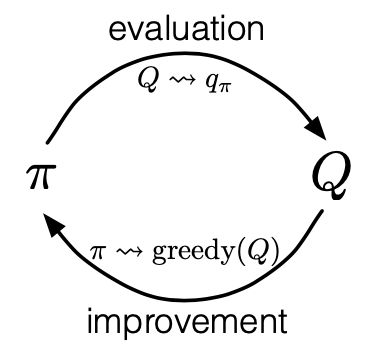

A related approach is the policy iteration method, where the agent alternates between policy evaluation (estimating the value function for a given policy) and policy improvement (updating the policy to be greedy with respect to the current value function). This process continues until convergence, yielding an optimal policy that maximizes the expected return.

Reinforcement learning also requires careful management of the exploration-exploitation trade-off. A common approach is to use an $\epsilon$-greedy policy, where the agent selects a random action with probability $\epsilon$ (exploration) and follows the action with the highest expected reward with probability $1 - \epsilon$ (exploitation). Striking the right balance between exploration and exploitation is critical for ensuring that the agent can learn the optimal policy without getting stuck in suboptimal actions.

As an illustrative example, consider a simple grid-world environment where the agent navigates towards a goal while avoiding obstacles. The state space consists of the positions of the agent on the grid, and the actions correspond to movement directions (up, down, left, right). The agent receives a positive reward for reaching the goal and a negative reward for hitting an obstacle. The task is to learn a policy that maximizes the cumulative reward, guiding the agent to the goal as efficiently as possible while avoiding obstacles.

In conclusion, reinforcement learning provides a powerful framework for decision-making under uncertainty, where an agent learns through interactions with an environment by receiving feedback in the form of rewards. The objective is to learn a policy that maximizes the expected cumulative reward, which involves estimating value functions and managing the exploration-exploitation trade-off. The mathematical underpinnings of RL, including MDPs, value functions, and the Bellman equation, provide a formal basis for developing algorithms that enable agents to learn effective decision-making strategies in complex environments.

First, we will define the structure of our environment, including the state representation and the available actions. In our case, the state can be represented as the agent's position in the grid, and the actions will be the possible movements (up, down, left, right). Here’s how we can represent this in Rust:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

enum Action {

Up,

Down,

Left,

Right,

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

struct State {

x: usize,

y: usize,

}

struct GridWorld {

width: usize,

height: usize,

goal: State,

obstacles: Vec<State>,

}

impl GridWorld {

fn new(width: usize, height: usize, goal: State, obstacles: Vec<State>) -> Self {

GridWorld {

width,

height,

goal,

obstacles,

}

}

fn is_terminal(&self, state: State) -> bool {

state == self.goal || self.obstacles.contains(&state)

}

fn get_reward(&self, state: State) -> f32 {

if state == self.goal {

1.0 // Positive reward for reaching the goal

} else if self.obstacles.contains(&state) {

-1.0 // Negative reward for hitting an obstacle

} else {

0.0 // Neutral reward for regular states

}

}

}

fn main() {

// Example usage of the GridWorld

let goal = State { x: 2, y: 2 };

let obstacles = vec![State { x: 1, y: 1 }];

let grid_world = GridWorld::new(5, 5, goal, obstacles);

let state = State { x: 2, y: 2 };

println!("Is terminal: {}", grid_world.is_terminal(state));

println!("Reward: {}", grid_world.get_reward(state));

}

In this code, we define an Action enum to represent the possible movements of the agent. The State structure holds the agent's current position, while the GridWorld struct defines the environment's properties, including its dimensions, the goal state, and any obstacles. The is_terminal method checks if the agent's current state is terminal (either reaching the goal or hitting an obstacle), and the get_reward method provides the respective reward for the current state.

Next, we can simulate agent interactions with the environment. For simplicity, we will allow the agent to take random actions. Here is an example of how we can implement this in Rust:

use rand::Rng;

#[derive(Debug, PartialEq, Clone)]

struct State {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

#[derive(Debug)]

enum Action {

Up,

Down,

Left,

Right,

}

struct GridWorld {

width: i32,

height: i32,

terminus: State,

rewards: Vec<State>,

}

impl GridWorld {

fn new(width: i32, height: i32, terminus: State, rewards: Vec<State>) -> Self {

GridWorld { width, height, terminus, rewards }

}

fn is_terminal(&self, state: State) -> bool {

state == self.terminus

}

fn get_reward(&self, state: State) -> i32 {

if self.rewards.contains(&state) { 1 } else { 0 }

}

}

struct Agent {

position: State,

}

impl Agent {

fn new(start: State) -> Self {

Agent { position: start }

}

fn take_action(&mut self, action: Action) {

match action {

Action::Up => if self.position.y > 0 { self.position.y -= 1; },

Action::Down => if self.position.y < self.height() - 1 { self.position.y += 1; },

Action::Left => if self.position.x > 0 { self.position.x -= 1; },

Action::Right => if self.position.x < self.width() - 1 { self.position.x += 1; },

}

}

fn height(&self) -> i32 {

5 // assuming constant height for simplicity

}

fn width(&self) -> i32 {

5 // assuming constant width for simplicity

}

}

fn main() {

let world = GridWorld::new(5, 5, State { x: 4, y: 4 }, vec![State { x: 2, y: 2 }]);

let mut agent = Agent::new(State { x: 0, y: 0 });

while !world.is_terminal(agent.position.clone()) {

let action = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(0..4);

agent.take_action(match action {

0 => Action::Up,

1 => Action::Down,

2 => Action::Left,

_ => Action::Right,

});

let reward = world.get_reward(agent.position.clone());

println!("Agent Position: {:?}, Reward: {}", agent.position, reward);

}

println!("Final Position: {:?}", agent.position);

}

In this main function, we create a GridWorld environment and an Agent. The agent starts at the initial position, and in a loop, it takes random actions until it reaches a terminal state. The position and the reward received are printed at each step.

This example demonstrates the basic mechanics of reinforcement learning in Rust, encapsulating the core concepts of agents, environments, states, actions, and rewards. As we expand this framework, we can incorporate more sophisticated learning algorithms, enabling the agent to learn from its experiences and improve its policy over time. Reinforcement learning opens up a wide range of possibilities, and by using Rust, we can leverage its performance and safety features, which are particularly beneficial when building complex and computationally intensive applications in this domain.

14.2. Markov Decision Processes (MDP)

Reinforcement Learning (RL) builds its theoretical foundation on Markov Decision Processes (MDPs), which provide a rigorous mathematical framework for modeling decision-making under uncertainty. MDPs allow us to formalize environments in which an agent must make a sequence of decisions to maximize cumulative rewards. The key components of an MDP are states, actions, transition probabilities, rewards, and policies, each of which plays an essential role in shaping the agent's interactions with the environment and its learning process.

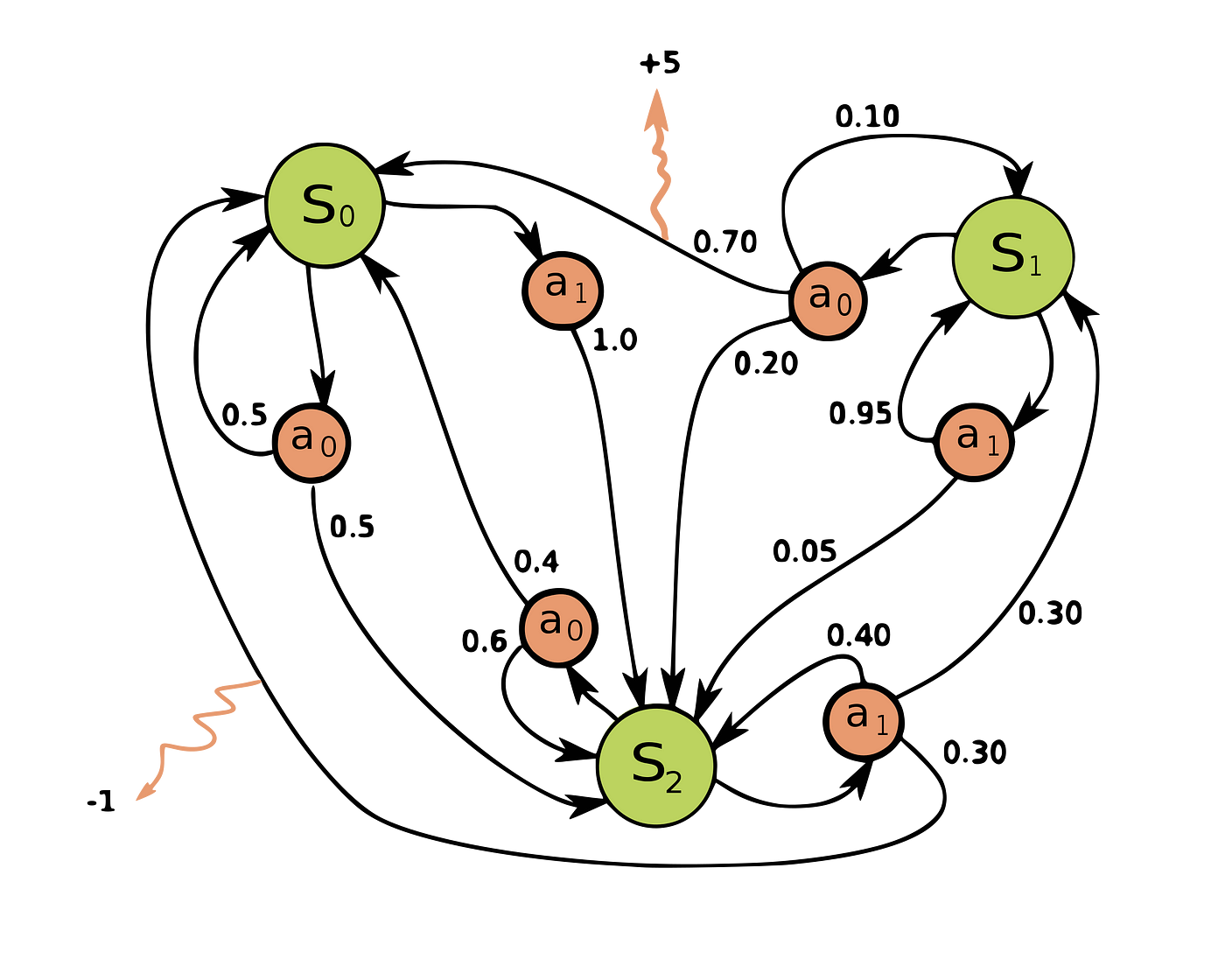

Figure 3: Illustration for MDP - Markov Decision Process

Formally, an MDP is defined as a tuple $(S, A, P, R, \gamma)$, where $S$ is the set of all possible states, $A$ is the set of all actions available to the agent, $P(s' \mid s, a)$ is the transition probability function that defines the probability of reaching state $s'$ from state $s$ by taking action $a$, $R(s, a)$ is the reward function that assigns a numerical reward to the agent for taking action aaa in state $s$, and $\gamma \in [0, 1]$ is the discount factor, which determines how much future rewards are discounted relative to immediate rewards. The agent's goal is to maximize the expected cumulative reward, also known as the return, over time by learning an optimal policy.

The agent's interaction with the environment in an MDP proceeds in discrete time steps. At each time step $t$, the agent observes the current state $S_t = s$, selects an action $A_t = a$, and transitions to a new state $S_{t+1} = s'$ according to the transition probability $P(s' \mid s, a)$. Simultaneously, the agent receives a reward $R(s, a)$, which provides feedback on the quality of the action chosen. The return, $G_t$, from time step ttt onward is defined as the discounted sum of future rewards:

$$ G_t = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k R_{t+k+1}, $$

where $\gamma^k$ discounts rewards received $k$-steps into the future, ensuring that immediate rewards are weighted more heavily than distant future rewards. The discount factor $\gamma$ helps balance the trade-off between short-term and long-term objectives.

At the core of MDPs is the Markov property, which states that the future state $S_{t+1}$ depends only on the current state $S_t$ and the action $A_t$, and not on the sequence of past states or actions. The property asserts that the future is independent of the past, given the present, meaning that all relevant information about the future behavior of the system is encapsulated in the current state. Mathematically, this property can be expressed as:

$$ P(S_{t+1} = s' \mid S_0, A_0, S_1, A_1, \dots, S_t, A_t) = P(S_{t+1} = s' \mid S_t, A_t). $$

In simpler terms, this equation states that the probability of transitioning to the next state $S_{t+1}$ depends only on the current state $S_t$ and the action $A_t$, without requiring any knowledge of how the system arrived at that state (i.e., the sequence of prior states and actions). The history of prior states and actions becomes irrelevant once the current state is known, leading to computational efficiency in modeling complex systems.

This assumption allows for memoryless decision processes where the system does not have to retain a complete record of the past, but can focus solely on the current state. In practical terms:

Simplification: By removing the need to consider the entire history, MDPs enable more tractable solutions in environments with large state spaces.

Optimal Policies: With the Markov property, an optimal policy can be derived by considering only the current state, which drastically reduces the complexity of finding a solution.

Real-World Examples: In autonomous driving, for example, the next driving action is chosen based on the current road conditions, the position of other cars, and current speed, without needing to reference previous road conditions or speeds.

Additionally, the Markov property aligns with the principle of state sufficiency in many natural and artificial systems, where knowing the present configuration of a system is enough to predict its evolution, a concept that is frequently leveraged in reinforcement learning and stochastic processes.

The Markov property simplifies the agent's decision-making process by reducing the amount of information required to determine the next action. Instead of considering the entire history of previous states and actions, the agent can base its decisions solely on the current state. This property makes MDPs particularly tractable for developing efficient learning algorithms, as it allows for recursive relationships between the state, action, and reward functions.

The solution to an MDP involves learning an optimal policy $\pi^*(a \mid s)$, which maps each state $s \in S$ to an action $a \in A$, such that the expected cumulative reward is maximized. The value of a state under a policy $\pi$, known as the *state-value function* $V^\pi(s)$, is the expected return starting from state $s$ and following policy $\pi$:

$$ V^\pi(s) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ G_t \mid S_t = s \right] = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k R_{t+k+1} \mid S_t = s \right]. $$

Similarly, the action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$ represents the expected return when the agent takes action $a$ in state $s$ and subsequently follows policy $\pi$:

$$ Q^\pi(s, a) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ G_t \mid S_t = s, A_t = a \right]. $$

The goal of reinforcement learning is to discover the optimal policy $\pi^*$, which maximizes the expected return from any initial state. The optimal state-value function $V^*(s)$ and the optimal action-value function $Q^*(s, a)$ satisfy the *Bellman optimality equations*, which provide a recursive decomposition of the value functions. The Bellman optimality equation for the state-value function is:

$$ V^*(s) = \max_{a \in A} \left[ R(s, a) + \gamma \sum_{s'} P(s' \mid s, a) V^*(s') \right], $$

and the corresponding equation for the action-value function is:

$$ Q^*(s, a) = R(s, a) + \gamma \sum_{s'} P(s' \mid s, a) \max_{a'} Q^*(s', a'). $$

These equations reflect the principle of optimality: the value of a state is the immediate reward obtained by taking the best possible action in that state, plus the discounted value of the subsequent state. Solving these equations provides the foundation for finding the optimal policy.

In practice, solving MDPs directly can be computationally challenging, especially in large state and action spaces. Dynamic programming techniques, such as value iteration and policy iteration, offer iterative methods for solving MDPs by updating estimates of the value functions until convergence. In value iteration, the state-value function is updated iteratively based on the Bellman equation, while policy iteration alternates between evaluating the current policy and improving it based on the updated value function. Both methods leverage the Markov property to efficiently propagate value estimates through the state space.

In summary, Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) provide a formal framework for modeling decision-making under uncertainty, where an agent seeks to maximize cumulative rewards over time. The MDP framework, built on the concepts of states, actions, transition probabilities, rewards, and policies, allows for a structured approach to learning optimal behaviors. The Markov property ensures that the future state depends only on the current state and action, simplifying the learning process and enabling efficient algorithms for policy optimization. Through the recursive nature of the Bellman equations, MDPs offer a powerful tool for reinforcement learning, guiding agents in their quest to learn optimal policies in complex environments.

In practical terms, implementing MDPs in Rust requires a structured approach to encapsulate the various components of an MDP. First, we can define the state, action, and reward structures using Rust's type system to ensure type safety and clarity. Below is a basic implementation that outlines the structure of an MDP:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub struct State {

pub id: usize,

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub struct Action {

pub id: usize,

}

pub struct Transition {

pub from: State,

pub action: Action,

pub to: State,

pub probability: f64,

}

pub struct Reward {

pub state: State,

pub action: Action,

pub value: f64,

}

pub struct MDP {

states: Vec<State>,

actions: Vec<Action>,

transitions: Vec<Transition>,

rewards: Vec<Reward>,

discount_factor: f64,

}

impl MDP {

pub fn new(states: Vec<State>, actions: Vec<Action>, discount_factor: f64) -> Self {

MDP {

states,

actions,

transitions: Vec::new(),

rewards: Vec::new(),

discount_factor,

}

}

pub fn add_transition(&mut self, from: State, action: Action, to: State, probability: f64) {

self.transitions.push(Transition { from, action, to, probability });

}

pub fn add_reward(&mut self, state: State, action: Action, value: f64) {

self.rewards.push(Reward { state, action, value });

}

pub fn get_reward(&self, state: State, action: Action) -> f64 {

for reward in &self.rewards {

if reward.state == state && reward.action == action {

return reward.value;

}

}

0.0 // Default reward if not found

}

pub fn get_next_state(&self, state: State, action: Action) -> Vec<(State, f64)> {

self.transitions.iter()

.filter(|t| t.from == state && t.action == action)

.map(|t| (t.to, t.probability))

.collect()

}

}

fn main() {

// Example usage of MDP

let states = vec![State { id: 1 }, State { id: 2 }];

let actions = vec![Action { id: 1 }, Action { id: 2 }];

let discount_factor = 0.9;

let mut mdp = MDP::new(states.clone(), actions.clone(), discount_factor);

mdp.add_transition(State { id: 1 }, Action { id: 1 }, State { id: 2 }, 0.8);

mdp.add_transition(State { id: 1 }, Action { id: 2 }, State { id: 1 }, 0.2);

mdp.add_reward(State { id: 2 }, Action { id: 1 }, 10.0);

let next_states = mdp.get_next_state(State { id: 1 }, Action { id: 1 });

for (next_state, probability) in next_states {

println!("Next state: {:?}, Probability: {}", next_state, probability);

}

let reward = mdp.get_reward(State { id: 2 }, Action { id: 1 });

println!("Reward for action: {}", reward);

}

In this implementation, we define the structures for the states, actions, transitions, and rewards, encapsulated within the MDP struct. The add_transition and add_reward methods allow for the dynamic construction of an MDP, which can then be used to simulate decision-making processes. The get_reward method retrieves the reward associated with a given state-action pair, while get_next_state provides the possible next states and their respective probabilities based on the current state and action.

To simulate the decision-making process within this MDP framework, we can execute a simple policy evaluation. For instance, we can create a policy that selects actions based solely on the highest expected reward. The following code snippet illustrates how this can be achieved:

pub fn evaluate_policy(mdp: &MDP, initial_state: State, steps: usize) {

let mut current_state = initial_state;

for _ in 0..steps {

let mut action_rewards: Vec<(Action, f64)> = mdp.actions.iter()

.map(|action| (action.clone(), mdp.get_reward(current_state, *action)))

.collect();

action_rewards.sort_by(|a, b| b.1.partial_cmp(&a.1).unwrap()); // Sort by reward

if let Some((best_action, _)) = action_rewards.first() {

println!("State: {:?}, Action: {:?}", current_state, best_action);

let next_states = mdp.get_next_state(current_state, *best_action);

// Choose a next state based on probabilities and transition

for (next_state, probability) in next_states {

println!("Transitioning to state: {:?} with probability: {}", next_state, probability);

current_state = next_state; // For simplicity, we just transition to the first available state

break;

}

}

}

}

In this function, we start from an initial state and for a specified number of steps, we evaluate the best action based on the expected reward. By sorting the actions according to their rewards, we can easily determine the best course of action at each step. After selecting an action, we retrieve the possible next states and transition accordingly. This simulation allows us to experiment with different policies and observe their impact on the agent's behavior and the overall performance of the MDP.

In summary, Markov Decision Processes offer a solid foundation for modeling decision-making in reinforcement learning. By encapsulating the key elements—states, actions, transition probabilities, rewards, and policies—MDPs provide a structured way to design and analyze learning algorithms. Through practical implementations in Rust, we can simulate complex decision-making scenarios and explore the effects of various strategies, enhancing our understanding of reinforcement learning concepts and their applications.

14.3 Dynamic Programming in RL

Dynamic programming (DP) plays a pivotal role in reinforcement learning (RL), especially for solving Markov Decision Processes (MDPs). MDPs serve as the mathematical foundation for decision-making problems where outcomes are influenced both by the agent’s actions and by inherent randomness in the environment. Dynamic programming techniques, including policy iteration and value iteration, offer systematic approaches to derive optimal policies and value functions in the context of reinforcement learning. Both of these techniques rely fundamentally on the Bellman equations, which define recursive relationships between the values of states and the actions taken from those states.

The Bellman equations provide a framework for understanding how future rewards can be used to evaluate the desirability of current actions. For a given policy $\pi$, the state-value function $V^\pi(s)$ represents the expected return (the sum of discounted future rewards) starting from state sss and following policy $\pi$. The Bellman equation for the value function under a fixed policy is given by:

$$ V^\pi(s) = \sum_{a \in A} \pi(a \mid s) \sum_{s' \in S} P(s' \mid s, a) \left[ R(s, a, s') + \gamma V^\pi(s') \right], $$

where $A$ represents the set of actions, $S$ represents the set of states, $P(s' \mid s, a)$ is the transition probability from state sss to state $s'$ given action $a$, $R(s, a, s')$ is the immediate reward obtained for transitioning from state $s$ to $s'$ under action $a$, and $\gamma \in [0,1]$ is the discount factor, which determines the weight of future rewards relative to immediate ones. The Bellman equation expresses the value of a state as the expected immediate reward plus the discounted value of the next state, averaged over all possible actions and transitions. This recursive formulation allows us to compute the value of each state by breaking down the complex problem of future rewards into smaller, manageable pieces.

The goal of reinforcement learning is to find an optimal policy $\pi^*$ that maximizes the expected return. This leads us to the concept of the optimal value function $V^*(s)$, which represents the maximum expected return obtainable from any state sss. The optimal value function satisfies the Bellman optimality equation:

$$ V^*(s) = \max_{a \in A} \sum_{s' \in S} P(s' \mid s, a) \left[ R(s, a, s') + \gamma V^*(s') \right]. $$

In this equation, the value of a state is defined as the maximum expected reward achievable by choosing the best possible action $a$ in state $s$, followed by the optimal policy thereafter. Solving this equation across all states yields the optimal state-value function, from which an optimal policy can be derived.

The value iteration algorithm is one of the most direct approaches for computing the optimal value function. It starts with an arbitrary initial value function $V_0(s)$ and iteratively updates it using the Bellman optimality equation. At each iteration $k$, the value function is updated according to:

$$ V_{k+1}(s) = \max_{a \in A} \sum_{s' \in S} P(s' \mid s, a) \left[ R(s, a, s') + \gamma V_k(s') \right]. $$

This iterative process continues until the values converge, typically defined as the maximum change in the value function across all states being smaller than a predefined threshold $\epsilon$. Formally, convergence occurs when:

$$ \max_s |V_{k+1}(s) - V_k(s)| < \epsilon. $$

Upon convergence, the value function $V^*(s)$ represents the optimal expected return for each state, and the optimal policy $\pi^*(s)$ can be extracted by selecting the action that maximizes the expected return at each state:

$$ \pi^*(s) = \arg \max_{a \in A} \sum_{s' \in S} P(s' \mid s, a) \left[ R(s, a, s') + \gamma V^*(s') \right]. $$

In contrast to value iteration, policy iteration is another dynamic programming method that alternates between two phases: policy evaluation and policy improvement. In the policy evaluation phase, the value function for a given policy $\pi$ is computed by solving the Bellman equation for $V^\pi(s)$. This process is typically carried out iteratively, as with value iteration, until the value function converges. In the policy improvement phase, the current policy is updated by making it greedy with respect to the newly computed value function. That is, the policy is improved by selecting the action that maximizes the expected return at each state:

$$ \pi_{k+1}(s) = \arg \max_{a \in A} \sum_{s' \in S} P(s' \mid s, a) \left[ R(s, a, s') + \gamma V_k(s') \right]. $$

These two phases are alternated until the policy no longer changes, indicating that the optimal policy has been found. Policy iteration often converges faster than value iteration because it directly improves the policy after each evaluation step, but it requires solving the policy evaluation step exactly or approximately at each iteration.

Both value iteration and policy iteration leverage the recursive nature of the Bellman equations to break down the complex problem of optimizing over an infinite horizon into simpler subproblems that can be solved iteratively. These dynamic programming methods are foundational in reinforcement learning because they provide a principled way to compute optimal policies and value functions, enabling agents to make decisions that maximize long-term rewards in stochastic environments.

In conclusion, dynamic programming methods in reinforcement learning, such as value iteration and policy iteration, are powerful techniques for solving MDPs. By leveraging the Bellman equations, these methods allow agents to systematically compute optimal value functions and derive optimal policies, making them essential tools for decision-making under uncertainty. Through their iterative nature, these algorithms progressively refine the agent's understanding of the environment, leading to optimal decision-making strategies over time.

To illustrate how to implement dynamic programming in Rust, we will consider a simple MDP with a finite state and action space. Below is an example implementation of the value iteration algorithm in Rust:

use std::f64;

const GAMMA: f64 = 0.9; // Discount factor

const THRESHOLD: f64 = 1e-6; // Convergence threshold

fn value_iteration(states: usize, actions: usize, transition_probabilities: &Vec<Vec<Vec<f64>>>, rewards: &Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut value_function = vec![0.0; states];

loop {

let mut new_value_function = value_function.clone();

for s in 0..states {

let mut max_value = f64::NEG_INFINITY;

for a in 0..actions {

let expected_value = (0..states).map(|s_prime| {

transition_probabilities[s][a][s_prime] * (rewards[s][a] + GAMMA * value_function[s_prime])

}).sum::<f64>();

max_value = max_value.max(expected_value);

}

new_value_function[s] = max_value;

}

// Check for convergence

let delta = new_value_function.iter().zip(&value_function)

.map(|(new_v, old_v)| (new_v - old_v).abs())

.fold(0.0, f64::max);

if delta < THRESHOLD {

break;

}

value_function = new_value_function;

}

value_function

}

fn main() {

// Define a simple MDP with 3 states and 2 actions

let states = 3;

let actions = 2;

let transition_probabilities = vec![

vec![

vec![0.7, 0.3, 0.0], // Action 0 from state 0

vec![0.0, 0.4, 0.6], // Action 1 from state 0

],

vec![

vec![0.0, 0.8, 0.2], // Action 0 from state 1

vec![0.0, 0.0, 1.0], // Action 1 from state 1

],

vec![

vec![0.5, 0.5, 0.0], // Action 0 from state 2

vec![0.0, 0.0, 1.0], // Action 1 from state 2

],

];

let rewards = vec![

vec![5.0, 10.0], // Rewards for state 0

vec![0.0, 0.0], // Rewards for state 1

vec![0.0, 0.0], // Rewards for state 2

];

let optimal_value_function = value_iteration(states, actions, &transition_probabilities, &rewards);

println!("Optimal value function: {:?}", optimal_value_function);

}

In this implementation, we define a simple MDP with three states and two actions. The transition_probabilities matrix represents the probability of transitioning from one state to another given an action, while the rewards matrix provides the immediate rewards associated with each action in each state. The value_iteration function updates the value function iteratively until the maximum change across the states is below a specified threshold, indicating convergence.

The policy iteration algorithm is another dynamic programming technique used to solve MDPs. It consists of two main steps: policy evaluation and policy improvement. In the policy evaluation step, we compute the value function for a fixed policy using the Bellman equation. In the policy improvement step, we derive a new policy by selecting actions that maximize the expected value based on the current value function. This process repeats until the policy stabilizes.

Implementing policy iteration in Rust adds another layer of complexity, but it follows a similar structure to value iteration. Below is a simplified version of a policy iteration algorithm:

fn policy_iteration(states: usize, actions: usize, transition_probabilities: &Vec<Vec<Vec<f64>>>, rewards: &Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> (Vec<f64>, Vec<usize>) {

let mut policy = vec![0; states]; // Initialize policy arbitrarily

let mut value_function = vec![0.0; states];

loop {

// Policy Evaluation

loop {

let mut new_value_function = value_function.clone();

for s in 0..states {

let a = policy[s];

new_value_function[s] = (0..states).map(|s_prime| {

transition_probabilities[s][a][s_prime] * (rewards[s][a] + GAMMA * value_function[s_prime])

}).sum();

}

let delta = new_value_function.iter().zip(&value_function)

.map(|(new_v, old_v)| (new_v - old_v).abs())

.fold(0.0, f64::max);

if delta < THRESHOLD {

break;

}

value_function = new_value_function;

}

// Policy Improvement

let mut policy_stable = true;

for s in 0..states {

let old_action = policy[s];

policy[s] = (0..actions).max_by(|&a, &b| {

let value_a = (0..states).map(|s_prime| {

transition_probabilities[s][a][s_prime] * (rewards[s][a] + GAMMA * value_function[s_prime])

}).sum::<f64>();

let value_b = (0..states).map(|s_prime| {

transition_probabilities[s][b][s_prime] * (rewards[s][b] + GAMMA * value_function[s_prime])

}).sum::<f64>();

value_a.partial_cmp(&value_b).unwrap()

}).unwrap();

if old_action != policy[s] {

policy_stable = false;

}

}

if policy_stable {

break;

}

}

(value_function, policy)

}

fn main() {

// Same MDP definition as before

let states = 3;

let actions = 2;

let transition_probabilities = vec![/* same as before */];

let rewards = vec![/* same as before */];

let (optimal_value_function, optimal_policy) = policy_iteration(states, actions, &transition_probabilities, &rewards);

println!("Optimal value function: {:?}", optimal_value_function);

println!("Optimal policy: {:?}", optimal_policy);

}

In this example, the policy_iteration function computes the optimal value function and policy for the given MDP. The policy is initialized arbitrarily, and the algorithm iterates through the policy evaluation and improvement steps until the policy no longer changes. The resulting optimal value function and policy are printed at the end of the main function.

Both value iteration and policy iteration demonstrate the powerful role dynamic programming plays in reinforcement learning. These algorithms provide systematic methods for determining optimal strategies in environments modeled as MDPs. By implementing these concepts in Rust, we not only solidify our understanding of reinforcement learning principles but also gain practical experience in building efficient algorithms that can be extended to more complex scenarios, paving the way for further exploration in the field of machine learning. As we continue to delve into more advanced topics in reinforcement learning, the foundational concepts covered in this chapter will serve as invaluable tools for navigating the complexities of real-world problems.

14.4 Monte Carlo Methods in RL

Monte Carlo methods are a fundamental component of reinforcement learning (RL) and provide a powerful framework for estimating value functions and optimizing policies through random sampling. Unlike dynamic programming approaches, which rely on having a complete model of the environment, Monte Carlo methods are model-free, meaning they allow an agent to learn directly from its interactions with the environment without requiring explicit knowledge of the transition probabilities or reward dynamics. The core idea behind Monte Carlo methods is to approximate the value of states or state-action pairs by averaging the returns from episodes of experience, using these estimates to guide the agent’s policy towards higher cumulative rewards.

Figure 4: Monte Carlo method in Reinforcement Learning.

Formally, the Monte Carlo method involves the computation of value functions based on observed returns. Let $G_t$ represent the return, or cumulative discounted reward, obtained from time step $t$ onward during an episode. For a given state $s$, the state-value function $V(s)$ is defined as the expected return when starting from state $s$ and following the current policy $\pi$:

$$ V(s) = \mathbb{E}_\pi [G_t \mid S_t = s]. $$

In Monte Carlo methods, this expectation is approximated by averaging the returns observed from actual episodes where the agent encounters state $s$. If the agent visits state $s$ multiple times during different episodes, the value of the state is updated iteratively by averaging the observed returns. Specifically, after $N(s)$ visits to state $s$, the value estimate $V(s)$ is updated as:

$$ V(s) = \frac{1}{N(s)} \sum_{i=1}^{N(s)} G_t^{(i)}, $$

where $G_t^{(i)}$ represents the return observed during the $i$-th visit to state $s$. This process of averaging returns over multiple episodes enables the agent to build up an accurate estimate of the value function without requiring knowledge of the environment’s transition dynamics.

Monte Carlo methods can be extended to estimate the action-value function $Q(s, a)$, which represents the expected return when taking action aaa in state sss and then following policy $\pi$. The action-value function is defined as:

$$ Q(s, a) = \mathbb{E}_\pi [G_t \mid S_t = s, A_t = a]. $$

As with state-value estimates, Monte Carlo methods update the action-value estimates by averaging the returns observed when the agent takes action aaa in state sss across different episodes. This provides a way to evaluate not only the quality of individual states but also the quality of state-action pairs, guiding the agent toward selecting actions that maximize future rewards.

A key advantage of Monte Carlo methods is that they do not require the agent to compute expectations over the transition probabilities $P(s' \mid s, a)$, which may be unknown or difficult to model in many environments. Instead, the agent learns directly from its own experience by sampling episodes, making Monte Carlo methods particularly suitable for model-free environments. This also makes these methods applicable in a wide variety of real-world scenarios where constructing an accurate model of the environment is infeasible or prohibitively complex.

An important distinction within Monte Carlo methods is between first-visit and every-visit approaches. In the first-visit Monte Carlo method, the agent updates the value estimate of a state or state-action pair based only on the first time that state (or state-action pair) is visited within each episode. Formally, if $S_t = s$ is the first time the agent visits state sss during an episode, the value function is updated as:

$$ V(s) = \frac{1}{N_{\text{first}}(s)} \sum_{i=1}^{N_{\text{first}}(s)} G_t^{(i)}, $$

where $N_{\text{first}}$ counts the number of episodes in which state sss is visited for the first time. This method provides a low-variance estimate of the value function, as it considers only the first occurrence of a state in each episode, thus reducing the potential for redundant updates from repeated visits within the same episode.

In contrast, the every-visit Monte Carlo method updates the value estimate each time the state (or state-action pair) is encountered within an episode, regardless of whether it is the first visit. The value function is updated as:

$$ V(s) = \frac{1}{N_{\text{total}}(s)} \sum_{i=1}^{N_{\text{total}}(s)} G_t^{(i)}, $$

where $N_{\text{total}}$ counts the total number of times state sss is visited across all episodes. While this approach may lead to higher variance in the value estimates due to multiple updates within the same episode, it can lead to faster learning in environments where states are frequently revisited.

Monte Carlo methods also face the challenge of the exploration-exploitation trade-off, which is common in all reinforcement learning algorithms. To ensure that the agent explores the environment sufficiently, the policy used during learning must allow for exploration of less frequently visited states and actions. One common approach is to use an $\epsilon$-greedy policy, where the agent selects a random action with probability $\epsilon$ and selects the action with the highest estimated value with probability $1 - \epsilon$. This ensures that the agent explores the state space while gradually improving its policy based on the estimated value functions.

The convergence properties of Monte Carlo methods are well understood. Given sufficient exploration of the state space and assuming that the agent follows a stationary policy, the value estimates $V(s)$ and $Q(s, a)$ converge to their true values as the number of episodes increases. This is guaranteed by the law of large numbers, which ensures that the sample averages of returns converge to the expected return as the number of samples grows.

In summary, Monte Carlo methods form a cornerstone of reinforcement learning, providing a framework for model-free learning through random sampling of episodes. These methods are particularly advantageous in environments where the transition probabilities and rewards are unknown, allowing agents to learn directly from experience. The distinction between first-visit and every-visit methods offers flexibility in how value estimates are updated, with trade-offs in terms of variance and convergence speed. Through the use of sampled returns, Monte Carlo methods enable agents to estimate value functions and optimize policies, ultimately guiding their behavior toward maximizing cumulative rewards.

To illustrate the application of Monte Carlo methods in Rust, we can implement a simple grid-world environment. This environment serves as a classic example for testing RL algorithms. The grid consists of states that the agent can occupy, with certain states designated as terminal states. The agent receives rewards based on its actions, which it uses to update its value function estimates over time. Below is a basic implementation of Monte Carlo methods applied to a grid-world environment in Rust.

First, we define the grid-world environment along with the necessary structures to represent states and actions:

use rand::Rng;

use std::collections::HashMap;

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug)]

enum Action {

Up,

Down,

Left,

Right,

}

struct GridWorld {

grid: Vec<Vec<i32>>,

start: (usize, usize),

terminal_state: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn new(grid: Vec<Vec<i32>>, start: (usize, usize), terminal_state: (usize, usize)) -> Self {

GridWorld {

grid,

start,

terminal_state,

}

}

fn step(&self, state: (usize, usize), action: Action) -> ((usize, usize), f32) {

let (x, y) = state;

let (new_x, new_y) = match action {

Action::Up => (x.wrapping_sub(1), y),

Action::Down => (x + 1, y),

Action::Left => (x, y.wrapping_sub(1)),

Action::Right => (x, y + 1),

};

if self.is_valid_move(new_x, new_y) {

((new_x, new_y), self.grid[new_x][new_y] as f32)

} else {

(state, 0.0) // No reward if the move is invalid

}

}

fn is_valid_move(&self, x: usize, y: usize) -> bool {

x < self.grid.len() && y < self.grid[0].len()

}

}

Now that we have our grid-world environment set up, we can implement the Monte Carlo learning algorithm. The following code snippet demonstrates how to perform Monte Carlo policy evaluation using the first-visit method:

struct MonteCarlo {

returns: HashMap<(usize, usize), Vec<f32>>,

value_function: HashMap<(usize, usize), f32>,

}

impl MonteCarlo {

fn new() -> Self {

MonteCarlo {

returns: HashMap::new(),

value_function: HashMap::new(),

}

}

fn update(&mut self, episode: Vec<((usize, usize), f32)>) {

let mut visited: HashMap<(usize, usize), bool> = HashMap::new();

let mut total_return: f32 = 0.0;

for &((state_x, state_y), reward) in episode.iter().rev() {

total_return += reward;

if !visited.contains_key(&(state_x, state_y)) {

visited.insert((state_x, state_y), true);

self.returns.entry((state_x, state_y)).or_insert_with(Vec::new).push(total_return);

let avg_return: f32 = self.returns.get(&(state_x, state_y)).unwrap().iter().sum::<f32>() /

self.returns.get(&(state_x, state_y)).unwrap().len() as f32;

self.value_function.insert((state_x, state_y), avg_return);

}

}

}

}

The MonteCarlo struct maintains a record of returns and the estimated value function. The update method processes an episode, calculating the return for each state encountered and updating the value function accordingly.

To execute the Monte Carlo algorithm in a grid world, we can simulate episodes and apply the learned value function to improve the policy. Below is an example of how this might look in practice:

fn main() {

let grid = vec![

vec![0, 0, 0, 0],

vec![0, -1, 0, 0],

vec![0, 0, 0, 1],

];

let start = (0, 0);

let terminal_state = (2, 3);

let environment = GridWorld::new(grid, start, terminal_state);

let mut mc = MonteCarlo::new();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for _ in 0..1000 {

let mut episode = Vec::new();

let mut state = environment.start;

while state != environment.terminal_state {

let action = match rng.gen_range(0..4) {

0 => Action::Up,

1 => Action::Down,

2 => Action::Left,

_ => Action::Right,

};

let (next_state, reward) = environment.step(state, action);

episode.push((state, reward));

state = next_state;

}

mc.update(episode);

}

println!("Estimated Value Function: {:?}", mc.value_function);

}

This code simulates 1000 episodes in the grid world, where the agent selects random actions to explore different states. The MonteCarlo instance updates the value function based on the returns from the sampled episodes.

Through this implementation, we can observe the benefits of Monte Carlo methods in reinforcement learning, particularly their ability to learn directly from experience without requiring a model of the environment. By comparing the performance of Monte Carlo methods against dynamic programming approaches—such as policy iteration or value iteration—we can gain valuable insight into their effectiveness. Monte Carlo methods are particularly advantageous in environments where the state space is large or complex, as they can efficiently learn optimal policies through exploration and exploitation of the environment.

In conclusion, Monte Carlo methods provide a robust and intuitive approach to reinforcement learning, enabling agents to learn from the outcomes of their actions in a principled manner. The application of these methods in Rust not only illustrates their practical implementation but also highlights the power of random sampling techniques in the realm of machine learning.

14.5 Temporal-Difference Learning

Temporal-Difference (TD) learning is a foundational technique in reinforcement learning (RL), combining the strengths of both Monte Carlo methods and dynamic programming. Unlike Monte Carlo methods, which update value estimates only at the end of complete episodes, TD learning allows for incremental updates at each time step, even before the episode concludes. This property makes TD learning highly effective for online learning, where agents must make real-time updates to their value functions based on partial observations. The central idea behind TD learning is bootstrapping: updating estimates of future rewards using other estimates rather than waiting for a complete outcome. This bootstrapping mechanism enables TD learning to provide fast, online learning, making it particularly well-suited for environments where long sequences of actions must be taken before achieving a terminal state.

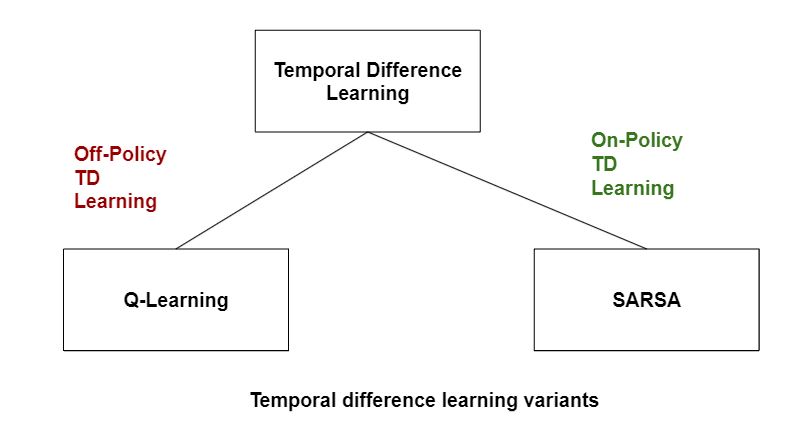

Figure 5: Category of TD learning.

The simplest and most fundamental version of TD learning is TD(0), which focuses on updating the value of a state based on the immediate reward received and the estimated value of the next state. Formally, let $V(s)$ represent the value of a state $s$, defined as the expected return when starting from state $s$ and following a policy $\pi$. The TD(0) update rule for the state-value function is given by:

$$ V(s) \leftarrow V(s) + \alpha \left( r + \gamma V(s') - V(s) \right), $$

where $r$ is the reward received after transitioning from state sss to state $s'$, $\gamma \in [0, 1]$ is the discount factor, and $\alpha$ is the learning rate, which controls the magnitude of the update. The term $r + \gamma V(s') - V(s)$ is known as the TD error, and it represents the difference between the current estimate of the value of state $s$ and the updated estimate based on the next state $s'$. This error is used to adjust the value of sss incrementally, allowing the agent to refine its estimates of the state values with each interaction with the environment.

A key advantage of TD learning is that it does not require a complete model of the environment’s transition dynamics $P(s' \mid s, a)$, unlike dynamic programming methods. Instead, the agent updates its value estimates directly from experience, making TD methods model-free. This makes TD learning particularly useful in environments where modeling the transition dynamics is complex or infeasible. The incremental nature of TD(0) also allows the agent to update its value estimates after every time step, leading to faster convergence than methods that rely on full episodes, such as Monte Carlo.

TD learning can be extended to action-value functions, leading to powerful algorithms such as SARSA and Q-learning. In SARSA (State-Action-Reward-State-Action), the agent updates the value of state-action pairs $Q(s, a)$ based on the rewards and transitions observed under its current policy. The action-value function $Q(s, a)$ represents the expected return when taking action aaa in state sss and then following the policy $\pi$. The SARSA update rule is similar to the TD(0) update rule but applied to state-action pairs. If the agent transitions from state sss and takes action aaa, receiving reward $r$ and then selecting action $a'$ in the next state $s'$, the SARSA update is given by:

$$ Q(s, a) \leftarrow Q(s, a) + \alpha \left( r + \gamma Q(s', a') - Q(s, a) \right). $$

SARSA is an on-policy algorithm, meaning it updates the action-value function based on the actions taken by the current policy. This means that the agent learns the value of the policy it is currently following, which can be suboptimal during learning but ensures that the policy learned is directly related to the agent's behavior. The update depends on the next action a′a'a′ that the agent chooses based on its policy, making SARSA sensitive to the exploration-exploitation trade-off embedded in the policy.

In contrast, Q-learning is an off-policy algorithm that seeks to learn the optimal action-value function, independent of the agent’s current behavior. Instead of updating the action-value function based on the agent's next action, Q-learning updates the action-value function based on the maximum expected future reward from the next state. The Q-learning update rule is given by:

$$ Q(s, a) \leftarrow Q(s, a) + \alpha \left( r + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s', a') - Q(s, a) \right), $$

where $\max_{a'} Q(s', a')$ represents the maximum estimated action-value in the next state $s'$. This update rule allows the agent to learn the optimal policy, regardless of the actions it takes during learning. Q-learning essentially assumes that the agent will always act optimally in the future, even if it is currently exploring suboptimal actions. This characteristic makes Q-learning a powerful algorithm for learning the optimal policy, but it also means that the agent's exploration strategy does not affect the learned policy as strongly as in SARSA.

The primary difference between SARSA and Q-learning lies in how they handle the exploration-exploitation trade-off during learning. SARSA learns based on the actual actions the agent takes, making it more sensitive to the exploration strategy (such as $\epsilon$-greedy), while Q-learning learns the optimal policy regardless of how the agent explores. This leads to different behaviors during the learning process: SARSA tends to learn safer policies that account for the agent’s exploration, whereas Q-learning can sometimes overestimate the value of states if the agent does not explore enough.

Both SARSA and Q-learning illustrate the flexibility of TD learning methods in reinforcement learning. By continuously updating value estimates from raw experience, TD learning algorithms enable agents to learn effective policies in a wide range of environments. The bootstrapping nature of TD methods allows for efficient, incremental updates, while their model-free characteristics make them applicable to environments where the transition dynamics are unknown or difficult to model.

In conclusion, Temporal-Difference (TD) learning stands at the core of reinforcement learning, offering a powerful blend of real-time updates and model-free learning. By incrementally updating value estimates based on the agent's experience, TD methods such as TD(0), SARSA, and Q-learning allow agents to refine their understanding of the environment without the need for complete episodes or explicit models. These algorithms provide a robust framework for learning optimal policies, balancing exploration and exploitation, and adapting to complex and dynamic environments.

To implement TD learning algorithms in Rust, we can create a simple example that utilizes the Q-learning approach in a grid-world environment. Below is a basic outline of how such an implementation might look. First, we define the environment, including states, actions, and rewards:

struct GridWorld {

grid: Vec<Vec<i32>>,

agent_pos: (usize, usize),

}

impl GridWorld {

fn new() -> Self {

GridWorld {

grid: vec![vec![0, 0, 0], vec![0, -1, 0], vec![0, 0, 1]],

agent_pos: (0, 0),

}

}

fn reset(&mut self) {

self.agent_pos = (0, 0);

}

fn step(&mut self, action: usize) -> (i32, (usize, usize)) {

let (x, y) = self.agent_pos;

let (new_x, new_y) = match action {

0 => (x.wrapping_sub(1), y), // Up

1 => (x + 1, y), // Down

2 => (x, y.wrapping_sub(1)), // Left

3 => (x, y + 1), // Right

_ => (x, y),

};

let clamped_x = new_x.clamp(0, 2);

let clamped_y = new_y.clamp(0, 2);

self.agent_pos = (clamped_x, clamped_y);

let reward = self.grid.get(clamped_x).and_then(|r| r.get(clamped_y)).unwrap_or(&0);

(reward.clone(), self.agent_pos)

}

}

In this implementation, the GridWorld struct represents a simple environment with a grid where the agent receives rewards based on its position. The step function processes the agent's action, updates its position, and returns the received reward along with the new position.

Next, we implement the Q-learning algorithm itself. This will include initializing the Q-table, selecting actions based on an exploration strategy (such as ε-greedy), and updating the Q-values based on the experiences gathered:

extern crate rand;

struct QLearningAgent {

q_table: Vec<Vec<f64>>,

learning_rate: f64,

discount_factor: f64,

exploration_rate: f64,

}

impl QLearningAgent {

fn new(num_states: usize, num_actions: usize, learning_rate: f64, discount_factor: f64, exploration_rate: f64) -> Self {

QLearningAgent {

q_table: vec![vec![0.0; num_actions]; num_states],

learning_rate,

discount_factor,

exploration_rate,

}

}

fn select_action(&self, state: usize) -> usize {

if rand::random::<f64>() < self.exploration_rate {

rand::random::<usize>() % self.q_table[state].len()

} else {

self.q_table[state]

.iter()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|a, b| a.1.partial_cmp(b.1).unwrap())

.map(|(index, _)| index)

.unwrap()

}

}

fn update_q_value(&mut self, state: usize, action: usize, reward: f64, next_state: usize) {

let best_next_action = self.q_table[next_state]

.iter()

.cloned()

.fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max);

self.q_table[state][action] += self.learning_rate * (reward + self.discount_factor * best_next_action - self.q_table[state][action]);

}

}

In this section, the QLearningAgent structure maintains a Q-table and implements methods for action selection and Q-value updates. The select_action function utilizes an ε-greedy strategy, while update_q_value applies the Q-learning update rule.

To see the entire learning process in action, we would run multiple episodes, allowing the agent to interact with the environment using the defined methods, and gradually improving its policy based on the rewards received:

fn main() {

let mut environment = GridWorld::new();

let mut agent = QLearningAgent::new(9, 4, 0.1, 0.99, 0.1);

for episode in 0..1000 {

environment.reset();

let mut done = false;

println!("Episode {}: Starting new episode", episode + 1);

while !done {

let state = environment.agent_pos.0 * 3 + environment.agent_pos.1; // Convert position to state index

let action = agent.select_action(state);

let (reward, next_pos) = environment.step(action);

let next_state = next_pos.0 * 3 + next_pos.1; // Convert next position to state index

println!(

"Agent position: {:?}, State: {}, Action: {}, Reward: {}, Next position: {:?}",

environment.agent_pos, state, action, reward, next_pos

);

agent.update_q_value(state, action, reward as f64, next_state);

// Print Q-table after update

println!("Updated Q-table for state {}: {:?}", state, agent.q_table[state]);

done = reward != 0; // Assuming 1 is the terminal state

}

println!("Episode {}: Ended\n", episode + 1);

}

}

In this main function, we set up the environment and agent, running a loop for a fixed number of episodes. During each episode, the agent interacts with the environment, updating its Q-values based on the feedback received from its actions. This structure not only demonstrates the TD learning process in practice but also provides ample opportunity for experimentation with various learning rates, discount factors, and exploration strategies.

Through this exploration of Temporal-Difference learning in Rust, we gain insight into how these techniques can be effectively implemented in a programming language known for its performance and safety. As we continue to dive deeper into reinforcement learning, understanding these foundational concepts will empower us to tackle more complex environments and challenges.

14.6 Function Approximation in RL

In reinforcement learning (RL), managing environments with vast or continuous state-action spaces poses a significant challenge, as it is often infeasible to represent each state-action pair explicitly. To address this, function approximation methods are employed, allowing agents to generalize from limited experience and estimate value functions or policies over a broader range of states. The fundamental idea behind function approximation is to learn a model that can infer the values for unseen states based on the patterns learned from a set of observed states, enabling agents to make informed decisions even in complex, high-dimensional environments. By approximating the value function $V(s)$, the action-value function $Q(s, a)$, or the policy $\pi(a \mid s)$, function approximation makes it possible for RL algorithms to scale to environments where traditional tabular methods would be computationally prohibitive.

Formally, the problem of approximating a value function can be described as finding a mapping from the state space (or state-action space) to a real-valued function that estimates the expected return. Let $V(s)$ be the state-value function, which represents the expected return from state sss under a policy $\pi$. Instead of storing the exact value of each state in a table, function approximation models $V(s)$ as a function of a set of parameters $\theta$, denoted by $V_\theta(s)$. The objective is to find the parameter vector $\theta$ that minimizes the error between the predicted value $V_\theta(s)$ and the true value $V(s)$. This error can be quantified by a loss function, typically the mean squared error:

$$ \mathcal{L}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ (V(s) - V_\theta(s))^2 \right], $$

where the expectation is taken over the distribution of states under the policy $\pi$. The parameters $\theta$ are then updated using gradient-based optimization techniques, such as stochastic gradient descent, to minimize the loss function. The update rule for θ\\thetaθ in gradient descent is given by:

$$ \theta \leftarrow \theta - \alpha \nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta), $$

where $\alpha$ is the learning rate, and $\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta)$ is the gradient of the loss function with respect to the parameters $\theta$. This process allows the agent to iteratively refine its estimates of the value function based on new data from its interactions with the environment.

Function approximation can be divided into two main categories: linear and non-linear approximation. In linear function approximation, the value function $V_\theta(s)$ is modeled as a linear combination of features derived from the state. Let $\phi(s)$ be a feature vector representing state sss, and let $\theta$ be a parameter vector. The linear approximation for the value function is given by:

$$ V_\theta(s) = \theta^T \phi(s) = \sum_{i=1}^d \theta_i \phi_i(s), $$

where $\phi_i(s)$ is the $i$-th feature, $\theta_i$ is the corresponding parameter, and $d$ is the number of features. Linear function approximation is computationally efficient and relatively simple to implement, as the parameter updates involve only linear operations. However, linear models are limited in their ability to capture complex relationships within the state space, especially in environments with significant non-linearities.

To address these limitations, non-linear function approximators, such as neural networks, are commonly used. A neural network can be viewed as a universal function approximator that can learn arbitrary non-linear mappings between inputs (states) and outputs (value estimates or action probabilities). For a given state $s$, a neural network with parameters $\theta$ outputs an estimate $V_\theta(s)$ by passing the feature vector $\phi(s)$ through multiple layers of non-linear transformations. Mathematically, a neural network with one hidden layer can be represented as:

$$ V_\theta(s) = \sigma(W_2 \cdot \sigma(W_1 \cdot \phi(s) + b_1) + b_2), $$

where $W_1$ and $W_2$ are weight matrices, $b_1$ and $b_2$ are bias vectors, and $\sigma(\cdot)$ is a non-linear activation function (such as the ReLU or sigmoid function). The parameters $W_1$, $W_2$, $b_1$, and $b_2$ are learned through gradient descent by minimizing the same type of loss function used in linear approximation. Neural networks offer much greater flexibility than linear models, allowing the agent to learn complex patterns in the state space that would be missed by simpler models.

One of the most successful applications of neural networks in reinforcement learning is deep Q-learning, where a deep neural network is used to approximate the action-value function $Q(s, a)$. In deep Q-learning, the Q-function is represented by a neural network $Q_\theta(s, a)$, which estimates the expected return for taking action aaa in state $s$. The parameters $\theta$ are updated by minimizing the TD error, which is the difference between the predicted Q-value and the target Q-value. The update rule is given by:

$$ \theta \leftarrow \theta + \alpha \left( r + \gamma \max_{a'} Q_\theta(s', a') - Q_\theta(s, a) \right) \nabla_\theta Q_\theta(s, a), $$

where $r$ is the reward, $\gamma$ is the discount factor, and $\max_{a'} Q_\theta(s', a')$ represents the maximum predicted Q-value for the next state $s'$. This approach, known as deep Q-learning, has been widely used in environments with large or continuous state spaces, such as video games and robotics, where traditional tabular methods are infeasible.

Function approximation introduces several challenges, particularly the risk of instability and divergence during learning. This is because function approximators like neural networks are sensitive to the choice of hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, network architecture) and may struggle with off-policy data, as in Q-learning. Techniques such as experience replay, where past experiences are stored and reused during training, and target networks, where a separate network is used to compute target values, are often employed to stabilize the learning process in deep reinforcement learning.

In conclusion, function approximation is an essential tool in reinforcement learning, enabling agents to generalize their knowledge across large or continuous state-action spaces. Linear function approximators provide a simple and efficient approach but may be limited in environments with complex dynamics. Non-linear function approximators, such as neural networks, offer significantly more flexibility and have been instrumental in the success of deep reinforcement learning. By learning approximate value functions or policies, agents can navigate and make decisions in complex environments that would otherwise be computationally intractable using traditional tabular methods.

To illustrate the application of function approximation in Rust, let's consider a simple implementation of a linear regression model for a value function. In this example, we will use a linear function approximator to predict the expected return from a given state. We can use the ndarray crate for handling multi-dimensional arrays, which is essential for our regression calculations. Below is a simple Rust implementation that demonstrates how to set up a linear regression model for RL tasks.

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

struct LinearRegressor {

weights: Array1<f64>,

}

impl LinearRegressor {

fn new(num_features: usize) -> Self {

Self {

weights: Array1::zeros(num_features),

}

}

fn predict(&self, features: &Array1<f64>) -> f64 {

self.weights.dot(features)

}

fn fit(&mut self, features: &Array2<f64>, targets: &Array1<f64>, learning_rate: f64, epochs: usize) {

for _ in 0..epochs {

let predictions = features.dot(&self.weights);

let errors = &predictions - targets;

// Gradient descent update

let gradient = features.t().dot(&errors) / features.nrows() as f64;

self.weights -= &(learning_rate * gradient);

}

}

}

fn main() {

let features = Array2::from_shape_vec((4, 2), vec![1.0, 0.0, 1.0, 1.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0]).unwrap();

let targets = Array1::from_vec(vec![0.0, 2.0, 2.0, 0.0]);

let mut model = LinearRegressor::new(2);

model.fit(&features, &targets, 0.01, 1000);

let state = Array1::from_vec(vec![0.0, 1.0]);

let prediction = model.predict(&state);

println!("Predicted value for state {:?}: {}", state, prediction);

}

In this example, we define a LinearRegressor struct that contains the weights of our linear model. The predict method computes the predicted value for a given state based on the learned weights. The fit method employs gradient descent to iteratively update the weights to minimize the error between predicted values and actual targets. This basic setup lays the foundation for using linear regression as a function approximator in RL contexts.

Moving beyond linear approaches, we may want to leverage non-linear function approximators to capture more complex dynamics within our environment. To do this in Rust, we can utilize libraries like tch-rs, which provides bindings to the popular PyTorch library, enabling us to construct and train neural networks seamlessly. Below is a simple example of how we might implement a neural network for approximating a value function.

use tch::{nn, Device, Tensor};

use tch::nn::{Module, OptimizerConfig};

struct NeuralNetwork {

model: nn::Sequential,

}

impl NeuralNetwork {

fn new(vs: &nn::Path) -> Self {

let model = nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs, 2, 64, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs, 64, 1, Default::default()));

Self { model }

}

fn predict(&self, input: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

self.model.forward(input)

}

fn fit(&mut self, input: &Tensor, target: &Tensor, optimizer: &mut nn::Optimizer) {

let prediction = self.predict(input);

let loss = prediction.mse_loss(target, tch::Reduction::Mean);

optimizer.backward_step(&loss);

}

}

fn main() {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let mut model = NeuralNetwork::new(&vs.root());

let mut optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

let input = Tensor::from_slice(&[1.0, 1.0]).view((1, 2)).to_kind(tch::Kind::Float).to(device);

let target = Tensor::from_slice(&[2.0]).view((1, 1)).to_kind(tch::Kind::Float).to(device);

for _ in 0..1000 {

model.fit(&input, &target, &mut optimizer);

}

let prediction = model.predict(&input);

println!("Predicted value for state {:?}: {:?}", input, prediction);

}

In this neural network implementation, we define a simple feedforward architecture with one hidden layer. The predict function utilizes the model to obtain predictions based on a given input tensor, while the fit method allows us to train the model by minimizing the mean squared error loss using the Adam optimizer. This provides a powerful way to approximate value functions in environments with complex state representations.

In summary, function approximation is a pivotal concept in reinforcement learning, particularly when faced with large or continuous state-action spaces. By employing linear and non-linear function approximators, we can effectively generalize our understanding of value functions and policies, thus enabling us to tackle more sophisticated RL tasks. The examples provided illustrate how to implement these techniques in Rust, empowering practitioners to leverage the power of function approximation in their RL endeavors.

14.7 Advanced Topics in Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement Learning (RL) has undergone considerable advancements, leading to the development of sophisticated algorithms that address the challenges of complex, high-dimensional environments. Among the most notable developments are deep reinforcement learning (DRL), policy gradient methods, and actor-critic architectures. These approaches integrate principles from both deep learning and RL to enable agents to tackle tasks that involve intricate state and action spaces, such as simulated robotics or high-dimensional games. This section delves into these advanced topics, providing a detailed mathematical and conceptual understanding of how they enhance RL performance in complex environments.