Chapter 16

Gradient Boosting Models

"The greatest glory in living lies not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall." — Nelson Mandela

Chapter 16 of MLVR provides a comprehensive guide to Gradient Boosting Models (GBMs), one of the most powerful techniques in machine learning for building predictive models. The chapter begins with an introduction to the fundamental concepts of Gradient Boosting, including how it works and why it is effective. It then delves into the details of the Gradient Boosting algorithm, explaining how models are iteratively improved through gradient descent. The chapter also explores the use of decision trees as base learners, the importance of regularization techniques, and the impact of hyperparameter tuning on model performance. Advanced variants of Gradient Boosting, such as XGBoost and LightGBM, are discussed, highlighting their innovations and advantages. Finally, the chapter covers practical applications of Gradient Boosting in various domains, providing readers with the knowledge and tools to implement these models in Rust for real-world problems.

16.1. Introduction to Gradient Boosting

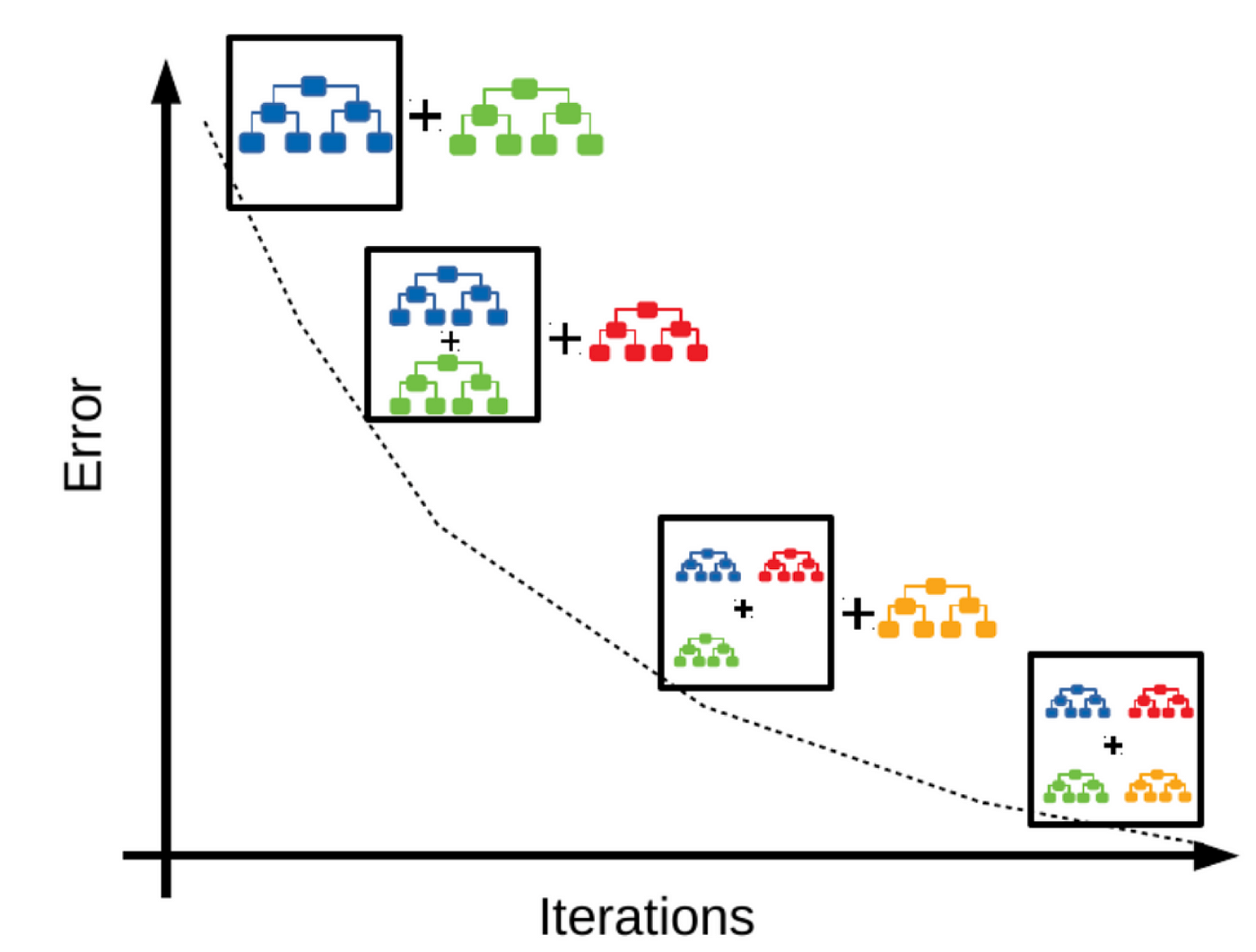

Gradient Boosting is an ensemble learning technique widely regarded for its strong performance in both classification and regression tasks. The core principle of Gradient Boosting lies in its ability to sequentially build a predictive model by combining multiple weak learners, typically decision trees. A weak learner is defined as a model that performs only slightly better than random guessing. However, through a process of iterative refinement, Gradient Boosting constructs a strong learner that captures complex patterns in the data by focusing on reducing the errors made by the previous learners. The method distinguishes itself by directly optimizing a loss function using gradient descent, which allows for flexibility in handling various types of data distributions and objective functions.

Figure 1: Illustration of Gradient Boosting.

Formally, let $\{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^N$ be a dataset consisting of input vectors $x_i$ and corresponding target values $y_i$, where $N$ is the number of data points. In regression tasks, the goal is to model the relationship between the input $x$ and the target $y$ using a function $F(x)$ that minimizes a specified loss function $\mathcal{L}(y, F(x))$. In Gradient Boosting, the predictive model is built as an additive model of weak learners:

$$ F(x) = F_0(x) + \sum_{m=1}^M \rho_m h_m(x), $$

where $F_0(x)$ is the initial model (often a simple constant), $h_m(x)$ is the $m$-th weak learner, and $\rho_m$ is a step size parameter that controls the contribution of each learner. The model is constructed iteratively, with each new weak learner $h_m(x)$ trained to minimize the residual errors (also known as residuals) of the previous model.

The key idea in Gradient Boosting is to optimize the loss function $\mathcal{L}(y, F(x))$ in a stage-wise manner. At each stage $m$, the model $F_m(x)$ is updated by adding a new weak learner $h_m(x)$, which is trained to approximate the negative gradient of the loss function with respect to the current model $F_{m-1}(x)$. Mathematically, the residuals at stage $m$ are given by:

$$ r_{im} = -\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}(y_i, F_{m-1}(x_i))}{\partial F_{m-1}(x_i)}, $$

which represents the direction in which the loss function decreases most rapidly. The new weak learner $h_m(x)$ is then fitted to these residuals, and the model is updated as:

$$ F_m(x) = F_{m-1}(x) + \rho_m h_m(x). $$

The step size $\rho_m$ is typically found by solving a one-dimensional optimization problem that minimizes the loss function along the direction of the new weak learner. This process is repeated for a specified number of iterations $M$, with each iteration improving the model by reducing the residuals from the previous stage.

One of the key advantages of Gradient Boosting is its ability to reduce overfitting, which is a common problem in machine learning models, especially when dealing with small datasets. This is achieved through techniques such as regularization and tree pruning. Regularization is typically applied to control the complexity of the model by penalizing the step sizes $\rho_m$ or the structure of the decision trees used as weak learners. L2 regularization, for instance, penalizes large weights in the trees, preventing the model from becoming too complex and fitting the noise in the data. Tree pruning, on the other hand, ensures that the decision trees do not grow too deep, which also helps in controlling overfitting by reducing model complexity.

Another important feature of Gradient Boosting is its capacity to handle a wide range of data distributions. By selecting different loss functions and weak learners, Gradient Boosting can be tailored to solve a variety of problems, including regression, classification, and ranking tasks. In Rust, implementing Gradient Boosting involves defining the loss function, computing gradients, fitting weak learners to the residuals, and updating the model iteratively. Rust's performance and memory management capabilities make it an ideal language for efficiently implementing and scaling Gradient Boosting algorithms to handle large datasets.

In conclusion, Gradient Boosting is a robust and versatile ensemble learning technique that constructs a strong learner by sequentially adding weak learners, each trained to minimize the residual errors of the previous models. By directly optimizing the loss function using gradient descent, Gradient Boosting offers flexibility in handling different types of tasks and loss functions. Its iterative nature, combined with regularization techniques, allows it to model complex patterns while mitigating the risk of overfitting, making it one of the most effective algorithms for both classification and regression tasks.

To illustrate how we can implement a basic Gradient Boosting model in Rust, we will utilize decision stumps—simplified decision trees that make predictions based on a single feature. This approach is particularly suited for demonstrating the principles of Gradient Boosting without the complexity introduced by full decision trees. We will apply our model to a simple classification task, perhaps using a synthetic dataset for clarity and ease of understanding.

First, let’s set up a basic structure for our Gradient Boosting implementation in Rust. We will define a DecisionStump struct that represents our weak learner and a GradientBoosting struct that will manage the overall boosting process. The DecisionStump will be trained on the residuals of the predictions, and the GradientBoosting struct will hold the collection of stumps.

#[derive(Debug)]

struct DecisionStump {

feature_index: usize,

threshold: f64,

prediction: f64,

}

impl DecisionStump {

fn fit(&self, x: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, y: &Vec<f64>, weights: &Vec<f64>) -> DecisionStump {

// Implement the logic to find the best feature and threshold for the stump

// This is a simplification for demonstration purposes

let (best_feature, best_threshold, best_prediction) = (0, 0.0, 0.0); // Placeholder

DecisionStump { feature_index: best_feature, threshold: best_threshold, prediction: best_prediction }

}

fn predict(&self, x: &Vec<f64>) -> f64 {

if x[self.feature_index] < self.threshold {

self.prediction

} else {

1.0 - self.prediction

}

}

}

struct GradientBoosting {

learning_rate: f64,

n_estimators: usize,

stumps: Vec<DecisionStump>,

}

impl GradientBoosting {

fn new(learning_rate: f64, n_estimators: usize) -> Self {

GradientBoosting {

learning_rate,

n_estimators,

stumps: Vec::new(),

}

}

fn fit(&mut self, x: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, y: &Vec<f64>) {

let mut predictions = vec![0.5; y.len()]; // Initial predictions

let weights = vec![1.0; y.len()]; // Equal weights for simplicity

for _ in 0..self.n_estimators {

let stump = DecisionStump { feature_index: 0, threshold: 0.0, prediction: 0.0 }.fit(x, y, &weights);

self.stumps.push(stump);

// Update predictions and weights (simplified)

for i in 0..y.len() {

predictions[i] += self.learning_rate * self.stumps.last().unwrap().predict(&x[i]);

}

}

}

fn predict(&self, x: &Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut predictions = vec![0.0; x.len()];

for stump in &self.stumps {

for (i, sample) in x.iter().enumerate() {

predictions[i] += self.learning_rate * stump.predict(sample);

}

}

predictions

}

}

In this example, we create a structure for DecisionStump, which includes methods for fitting the stump to the data and making predictions. The GradientBoosting struct manages the boosting process, including fitting the model to the data and making predictions based on the accumulated outputs of all stumps.

To demonstrate how our Gradient Boosting model would be applied in practice, we could utilize a simple synthetic dataset. For instance, we might generate a dataset with two features and a binary target variable. After training our model, we would evaluate its performance using accuracy or another relevant metric.

By implementing this basic version of Gradient Boosting in Rust, we highlight the underlying principles that make boosting effective, such as the iterative correction of errors and the combination of weak learners into a robust model. This approach not only provides a clear understanding of how Gradient Boosting operates but also showcases the flexibility and performance of Rust as a language for machine learning applications. As we delve deeper into the topic, we can explore enhancements to our model, such as using more complex tree structures, implementing regularization techniques, and optimizing hyperparameters to further improve performance on real-world datasets.

16.2. Gradient Boosting Algorithm

Gradient Boosting is an advanced ensemble learning technique that sequentially constructs a model by combining multiple weak learners, typically decision trees, to improve the overall prediction accuracy. At the heart of the Gradient Boosting algorithm lies the idea of iteratively minimizing a predefined loss function, which quantifies how well the model's predictions align with the true outcomes. This process of minimizing the loss function through iterative updates is what makes Gradient Boosting a powerful and flexible tool for both regression and classification tasks.

To formally describe Gradient Boosting, consider a dataset $\{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^N$, where $x_i \in \mathbb{R}^d$ represents the input features and $y_i \in \mathbb{R}$ represents the corresponding target values for a regression task (in classification, $y_i \in \{0, 1\}$. The objective of Gradient Boosting is to construct a function $F(x)$ that minimizes a loss function $\mathcal{L}(y, F(x))$. The loss function quantifies the error between the predicted output $F(x)$ and the true target $y$, and common choices for the loss function include Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression:

$$ \mathcal{L}(y, F(x)) = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N (y_i - F(x_i))^2, $$

or log loss for binary classification:

$$ \mathcal{L}(y, F(x)) = -\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \left( y_i \log(F(x_i)) + (1 - y_i) \log(1 - F(x_i)) \right). $$

The Gradient Boosting algorithm proceeds in an iterative, stage-wise fashion. Initially, a simple model $F_0(x)$ is chosen, often a constant value such as the mean of the target values in the case of regression:

$$ F_0(x) = \arg \min_c \sum_{i=1}^N \mathcal{L}(y_i, c). $$

At each subsequent stage mmm, a new model $h_m(x)$ (typically a decision tree) is added to the current model $F_{m-1}$, with the goal of improving the predictions by reducing the residual errors from the previous model. The residuals represent the direction in which the model's predictions need to be adjusted in order to reduce the overall error. Formally, the residuals are computed as the negative gradient of the loss function with respect to the current model's predictions:

$$ r_{im} = -\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}(y_i, F_{m-1}(x_i))}{\partial F_{m-1}(x_i)}. $$

A new weak learner $h_m(x)$ is then trained to predict these residuals, and the model is updated as follows:

$$ F_m(x) = F_{m-1}(x) + \eta h_m(x), $$

where $\eta$ is the learning rate, a hyperparameter that controls the contribution of each new model to the overall ensemble. The learning rate plays a critical role in determining the performance of the Gradient Boosting algorithm. A smaller learning rate reduces the impact of each new model, which can help prevent overfitting but may require more iterations to achieve optimal performance. On the other hand, a larger learning rate accelerates the convergence of the algorithm but increases the risk of overshooting the optimal solution and overfitting to the training data.

The choice of the learning rate $\eta$ and the number of iterations $M$ is crucial for controlling the trade-off between model complexity and generalization. Typically, the learning rate is tuned through cross-validation, and the number of iterations is chosen to balance training accuracy with the risk of overfitting.

In each iteration of the Gradient Boosting algorithm, the weak learner $h_m(x)$ is fitted to minimize the residuals, which are the differences between the true values $y_i$ and the current model's predictions $F_{m-1}(x_i)$. This process can be viewed as solving a regression problem where the target values are the residuals, and the goal is to find a model that best fits these residuals. The updated model $F_m(x)$ is thus a weighted combination of the previous model and the new weak learner, where the weight is determined by the learning rate $\eta$.

The iterative nature of Gradient Boosting ensures that each new model focuses on the errors made by the previous models, progressively refining the predictions until the loss function is minimized. This stage-wise optimization approach allows Gradient Boosting to model complex, non-linear relationships in the data, making it highly effective for tasks that involve intricate data structures.

In practice, regularization techniques are often applied to prevent overfitting and improve the generalization ability of the model. These techniques include limiting the depth of the decision trees used as weak learners, applying L2 regularization to penalize large weights, and using stochastic techniques such as random subsampling of the training data (often referred to as Stochastic Gradient Boosting). These strategies help control the complexity of the model and reduce the risk of overfitting, particularly when working with small datasets or noisy data.

From an implementation perspective, Gradient Boosting in Rust involves several key steps: defining the loss function, computing the gradients of the loss function with respect to the current model's predictions, fitting decision trees to the residuals, and updating the model iteratively. Rust's high performance and concurrency capabilities make it well-suited for implementing Gradient Boosting at scale, allowing efficient handling of large datasets and enabling parallelized computation of the gradient updates and tree fitting.

In conclusion, Gradient Boosting is a versatile and powerful machine learning technique that constructs an ensemble of weak learners, each trained to minimize the residual errors of its predecessor. By iteratively optimizing a loss function using gradient descent, Gradient Boosting provides a flexible framework for solving both regression and classification problems. The careful tuning of hyperparameters such as the learning rate and the number of iterations, combined with regularization techniques, ensures that the model generalizes well to unseen data, making Gradient Boosting one of the most widely used and effective machine learning algorithms in practice.

In terms of the practical implementation of Gradient Boosting in Rust, we can create a simple framework that embodies the core principles outlined above. Below is a basic implementation that demonstrates how to build a Gradient Boosting regressor using decision trees as base learners.

struct DecisionTree {

// For simplicity, we'll assume the decision tree stores a single prediction for now

prediction: f64,

}

impl DecisionTree {

// Fit a simple decision tree model to the residuals (this is highly simplified)

fn fit(X: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, y: &Vec<f64>) -> Self {

// For simplicity, let's assume a very basic decision tree that only returns the mean of the residuals

let mean_prediction = y.iter().sum::<f64>() / y.len() as f64;

DecisionTree {

prediction: mean_prediction,

}

}

// Predict for each sample (this is also highly simplified)

fn predict(&self, X: &Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> Vec<f64> {

// Just return the same prediction for every sample

vec![self.prediction; X.len()]

}

}

struct GradientBoostingRegressor {

learning_rate: f64,

n_estimators: usize,

models: Vec<DecisionTree>,

residuals: Vec<f64>,

}

impl GradientBoostingRegressor {

fn new(learning_rate: f64, n_estimators: usize) -> Self {

GradientBoostingRegressor {

learning_rate,

n_estimators,

models: Vec::new(),

residuals: Vec::new(),

}

}

fn fit(&mut self, X: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, y: &Vec<f64>) {

let initial_prediction = self.initial_prediction(y);

self.residuals = y.iter().map(|&label| label - initial_prediction).collect();

for _ in 0..self.n_estimators {

let model = DecisionTree::fit(X, &self.residuals); // Fit a decision tree to the residuals

let predictions = model.predict(X);

let adjusted_predictions: Vec<f64> = predictions.iter().map(|&pred| pred * self.learning_rate).collect();

self.models.push(model);

self.residuals = self.residuals.iter().zip(adjusted_predictions.iter()).map(|(r, p)| r - p).collect();

}

}

fn predict(&self, X: &Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut final_predictions: Vec<f64> = vec![0.0; X.len()];

for model in &self.models {

let predictions = model.predict(X);

final_predictions.iter_mut().zip(predictions.iter()).for_each(|(f, &p)| *f += p);

}

final_predictions

}

fn initial_prediction(&self, y: &Vec<f64>) -> f64 {

y.iter().sum::<f64>() / y.len() as f64 // Mean of the target values

}

}

In this implementation, the GradientBoostingRegressor struct contains fields for the learning rate, the number of estimators (or decision trees), the models trained during the fitting process, and the residuals. The fit method initializes the training process by first computing an initial prediction, which is simply the mean of the target values. It then iteratively fits decision trees to the residuals and updates the residuals based on the predictions of these trees.

The predict method aggregates the predictions from all the models, adjusting them according to the learning rate. This example provides a foundation for building a Gradient Boosting model and experimenting with different configurations, including varying the learning rate and loss functions to see how they affect model performance.

To analyze the impact of the learning rate and loss functions, one can modify the fit method to allow for different loss functions, perhaps incorporating options for MSE and Log Loss. Furthermore, by conducting cross-validation and plotting the results, one can gain insights into how these hyperparameters influence the model's ability to generalize to unseen data.

In conclusion, the Gradient Boosting algorithm is a sophisticated yet intuitive approach to ensemble learning that exemplifies the power of iterative optimization. By understanding the fundamental ideas, conceptual processes, and practical implementation in Rust, we equip ourselves with the tools necessary to leverage Gradient Boosting effectively in various machine learning tasks.

16.3. Decision Trees as Base Learners

In machine learning, decision trees play a pivotal role, particularly in ensemble methods such as Gradient Boosting. They are often chosen as base learners due to their flexibility and ability to model complex, non-linear relationships without extensive preprocessing of the input data. Decision trees are non-parametric models, which means they do not assume a specific functional form for the relationship between the input features and the target variable. Instead, they recursively partition the data based on feature values, ultimately building a hierarchical structure that can capture intricate patterns and interactions within the data.

Mathematically, a decision tree operates by selecting the feature and corresponding threshold that best splits the data at each node, optimizing for a specific criterion, such as minimizing impurity or maximizing information gain. In the case of classification tasks, the most commonly used impurity measures are Gini impurity and entropy, while in regression, the criterion is often based on minimizing the variance or mean squared error (MSE).

Consider a dataset $\{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^N$, where $x_i \in \mathbb{R}^d$ represents the feature vector for the $i$-th data point, and $y_i \in \mathbb{R}$ is the corresponding target value. At each internal node of the tree, the algorithm searches for the feature $x_j$ and the threshold $\theta$ that best split the data into two subsets, such that the impurity is minimized in each subset. For classification, the Gini impurity $G$ for a node with $m$ samples is defined as:

$$ G = 1 - \sum_{k=1}^{K} p_k^2, $$

where $p_k$ is the proportion of samples belonging to class $k$, and $K$ is the total number of classes. The algorithm selects the feature and threshold that minimize the weighted average of the Gini impurity across the child nodes. In regression, the decision rule aims to minimize the variance in the target variable:

$$ \text{Variance} = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} (y_i - \bar{y})^2, $$

where $\bar{y}$ is the mean of the target values in the node.

At each step, the tree continues to split the data recursively until a stopping criterion is met. This criterion can be based on several factors, including reaching a maximum tree depth, having a minimum number of samples in a node, or achieving a level of purity in the nodes. The resulting tree structure consists of internal nodes, which represent decision rules, and leaf nodes, which represent the final predicted value (for regression) or class (for classification).

A major advantage of decision trees is their interpretability. The tree structure allows for a clear, visual representation of the decision-making process. Each path from the root node to a leaf node corresponds to a decision rule that can be easily understood and communicated, which makes decision trees particularly useful in domains where interpretability is critical, such as healthcare or finance.

However, decision trees are prone to overfitting, especially when allowed to grow deep. A deep tree can perfectly capture the relationships in the training data by creating highly specific rules for small subsets of the data. While this leads to a low training error, it often results in poor generalization to unseen data. To mitigate overfitting, techniques such as pruning are employed. Pruning involves cutting back branches of the tree that contribute little to the overall performance, effectively simplifying the model.

There are two main types of pruning: pre-pruning and post-pruning. Pre-pruning (also known as early stopping) involves halting the tree-building process when certain conditions are met, such as reaching a maximum depth or a minimum number of samples in a node. Post-pruning, on the other hand, allows the tree to grow fully before iteratively removing branches that do not improve the model’s performance. This is done by evaluating the performance of the pruned tree on a validation set and comparing it to the unpruned tree.

Another important factor to consider is the depth of the decision tree, as it determines the complexity of the model. A shallow tree, with few levels, may underfit the data by failing to capture important relationships, while a deep tree may overfit by learning noise and spurious patterns in the training data. The depth of the tree is therefore a hyperparameter that must be carefully tuned, often through cross-validation, to achieve a balance between bias and variance.

In ensemble methods like Gradient Boosting, decision trees serve as weak learners, meaning that each tree is relatively shallow, with limited depth, and only slightly better than random guessing. The power of Gradient Boosting comes from the sequential addition of these weak learners, where each tree is trained to correct the residual errors of the combined model from previous iterations. By limiting the depth of each individual tree, Gradient Boosting avoids the overfitting that a single deep tree might suffer from, while still capturing the complexity of the data through the aggregation of many trees.

From an implementation standpoint, constructing decision trees in Rust involves efficiently managing the recursive splitting of data and dynamically growing the tree structure. The computational cost of building a decision tree comes from evaluating all possible splits at each node, particularly when the number of features and data points is large. Rust’s performance characteristics, such as memory safety and concurrency support, make it well-suited for building scalable decision tree algorithms that can handle large datasets while maintaining efficiency.

In conclusion, decision trees form a fundamental component in machine learning, particularly as base learners in ensemble methods like Gradient Boosting. Their ability to model complex, non-linear relationships and their inherent interpretability make them versatile tools for a wide range of tasks. However, care must be taken to control the complexity of the tree, either through pruning or by limiting the depth, to ensure that the model generalizes well to unseen data. Through their sequential integration in methods like Gradient Boosting, decision trees become even more powerful, enabling them to capture intricate patterns while maintaining robustness against overfitting.

Implementing decision trees in Rust requires a solid understanding of the language's data structures and its ecosystem for machine learning. While Rust does not have as extensive a library ecosystem for machine learning compared to Python, it is still possible to create robust implementations thanks to its performance and safety features. To illustrate this, we can start with a simple implementation of a decision tree classifier. Below is a basic outline of how a decision tree might be structured in Rust.

#[derive(Debug)]

struct DecisionTree {

feature_index: Option<usize>,

threshold: Option<f64>,

left: Option<Box<DecisionTree>>,

right: Option<Box<DecisionTree>>,

prediction: Option<f64>,

}

impl DecisionTree {

fn new() -> Self {

DecisionTree {

feature_index: None,

threshold: None,

left: None,

right: None,

prediction: None,

}

}

fn fit(&mut self, features: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, labels: &Vec<f64>, depth: usize) {

// Stopping criteria: If all labels are the same, or max depth is reached

if labels.windows(2).all(|w| w[0] == w[1]) || depth == 0 {

self.prediction = Some(labels.iter().cloned().sum::<f64>() / labels.len() as f64);

return;

}

// Find the best split

let (best_feature, best_threshold) = self.find_best_split(features, labels);

self.feature_index = Some(best_feature);

self.threshold = Some(best_threshold);

// Split the dataset

let (left_features, left_labels, right_features, right_labels) = self.split_dataset(features, labels);

// Create child nodes

self.left = Some(Box::new(DecisionTree::new()));

self.left.as_mut().unwrap().fit(&left_features, &left_labels, depth - 1);

self.right = Some(Box::new(DecisionTree::new()));

self.right.as_mut().unwrap().fit(&right_features, &right_labels, depth - 1);

}

fn find_best_split(&self, features: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, labels: &Vec<f64>) -> (usize, f64) {

// Implementation of finding the best feature and threshold

// This is a placeholder for simplicity

(0, 0.0)

}

fn split_dataset(&self, features: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, labels: &Vec<f64>) -> (Vec<Vec<f64>>, Vec<f64>, Vec<Vec<f64>>, Vec<f64>) {

// Implementation of dataset splitting logic

(vec![], vec![], vec![], vec![])

}

// The predict method should take a dataset and return a vector of predictions

fn predict(&self, features: &Vec<Vec<f64>>) -> Vec<f64> {

features.iter().map(|sample| self.predict_single(sample)).collect()

}

// This method will predict for a single sample (already exists)

fn predict_single(&self, sample: &Vec<f64>) -> f64 {

if let Some(pred) = self.prediction {

return pred;

}

if sample[self.feature_index.unwrap()] < self.threshold.unwrap() {

self.left.as_ref().unwrap().predict_single(sample)

} else {

self.right.as_ref().unwrap().predict_single(sample)

}

}

}

In this simplified implementation of a decision tree, we define a DecisionTree struct with fields to store information about the feature used for splitting, the threshold value, the child nodes, and the prediction value. The fit method builds the tree by recursively splitting the dataset based on the best feature and threshold determined by the find_best_split method. The split_dataset method is responsible for partitioning the dataset into left and right splits based on the chosen feature and threshold. Finally, the predict method allows us to make predictions on new samples by traversing the tree.

Once we have our decision tree implemented, we can integrate it into a Gradient Boosting model. Gradient Boosting works by sequentially adding weak learners (in this case, decision trees) to minimize the loss function. Each subsequent tree is trained to correct the errors made by the previous trees. To adapt our decision tree into a boosting framework, we'll need to modify how we fit the trees based on the residuals of the predictions.

Here’s a conceptual outline of how this integration might look:

struct GradientBoosting {

trees: Vec<DecisionTree>,

learning_rate: f64,

n_estimators: usize,

}

impl GradientBoosting {

fn new(learning_rate: f64, n_estimators: usize) -> Self {

GradientBoosting {

trees: Vec::new(),

learning_rate,

n_estimators,

}

}

fn fit(&mut self, features: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, labels: &Vec<f64>) {

let mut predictions = vec![0.0; labels.len()];

for _ in 0..self.n_estimators {

let residuals: Vec<f64> = labels.iter().zip(predictions.iter())

.map(|(y, y_hat)| y - y_hat)

.collect();

let mut tree = DecisionTree::new();

tree.fit(features, &residuals, 5); // You can adjust depth as needed

// Predict for all samples in features

let tree_predictions = tree.predict(features);

predictions.iter_mut().zip(tree_predictions.iter())

.for_each(|(pred, tree_pred)| {

*pred += self.learning_rate * tree_pred;

});

self.trees.push(tree);

}

}

fn predict(&self, sample: &Vec<f64>) -> f64 {

let mut prediction = 0.0;

for tree in &self.trees {

prediction += tree.predict_single(sample);

}

prediction

}

}

In this GradientBoosting struct, we maintain a list of fitted trees and parameters for the learning rate and the number of estimators. The fit method works by iteratively calculating the residuals from the current predictions and fitting a new decision tree to those residuals. Each tree's predictions are then scaled by the learning rate and added to the overall predictions. This iterative process continues until the specified number of trees is reached.

In conclusion, using decision trees as base learners in Gradient Boosting models provides a robust approach to tackle complex datasets. Their ability to adaptively learn and correct errors makes them an invaluable tool in ensemble learning. Through practical implementations in Rust, one can leverage the power of these algorithms while benefiting from Rust's performance and safety features. By experimenting with various parameters such as tree depth and learning rates, users can optimize their models for better predictive performance, thus offering a compelling pathway for machine learning practitioners looking to integrate Rust into their workflows.

16.4. Regularization Techniques in Gradient Boosting

Regularization techniques are fundamental to enhancing the performance and robustness of Gradient Boosting models, which are inherently prone to overfitting due to their ability to model complex patterns in the data. Regularization plays a key role in controlling the balance between bias and variance, which is essential for ensuring that the model generalizes well to unseen data. In this section, we explore the mathematical principles underlying regularization in Gradient Boosting and discuss how to implement these techniques in Rust.

At the core of regularization in Gradient Boosting are several techniques, including shrinkage (or learning rate), subsampling, and constraints on tree growth. These techniques are designed to prevent the model from fitting too closely to the noise in the training data, thereby improving its generalization to new data points.

The learning rate, denoted by $\eta$, is a critical regularization parameter in Gradient Boosting that controls the contribution of each individual tree to the overall model. Formally, let $F_m(x)$ represent the model at stage $m$, where each new weak learner $h_m(x)$ is added to the model based on the residuals of the previous iteration:

$$ F_m(x) = F_{m-1}(x) + \eta h_m(x). $$

Here, $\eta \in (0, 1]$ acts as a scaling factor for the weak learner's contribution. A smaller learning rate $\eta$ reduces the impact of each new tree on the final model, which helps to prevent overfitting by making the model’s adjustments more gradual. However, a smaller learning rate requires more iterations (i.e., more trees) to achieve optimal performance. The idea is that by reducing the step size, the model avoids large, overconfident updates, thereby maintaining a smoother learning process. The trade-off is that while a smaller learning rate can reduce variance, it may also lead to underfitting if too few trees are used, increasing the bias of the model.

Another important regularization technique in Gradient Boosting is subsampling, which is closely related to the concept of stochastic gradient descent. Instead of using the entire training dataset to fit each new tree, a random subset of the data is sampled without replacement, and the weak learner is trained on this subset. Let $N$ be the total number of training samples, and let $\alpha \in (0, 1]$ represent the fraction of the data used for subsampling. Each tree is trained on $\alpha N$ randomly selected samples, rather than the full dataset. This introduces randomness into the model and reduces the correlation between the trees, which helps to decrease variance and avoid overfitting. Mathematically, subsampling modifies the objective function of the model by reducing the variance of the gradients computed for each subset of the data, leading to a more robust optimization process.

Tree constraints, such as limiting the maximum depth $d_{\text{max}}$ of each decision tree or the minimum number of samples required to split a node, serve as additional regularization techniques that control the complexity of the model. The depth of a tree directly influences the model's ability to capture intricate patterns in the data. A deeper tree can capture more complex relationships, but it also increases the risk of overfitting by modeling noise in the training data. Formally, let $T$ denote the decision tree structure, and let $d_{\text{max}}$ be the maximum depth of the tree. The complexity of the model increases exponentially with the depth of the tree, as the number of leaf nodes grows as $2^{d_{\text{max}}}$. Therefore, limiting the depth of each tree reduces the overall complexity of the model, promoting generalization by forcing the model to focus on the most significant patterns in the data.

In addition to tree depth, the minimum number of samples required to split a node, denoted as $n_{\text{min\_split}}$, serves as a regularization parameter that prevents the model from creating overly specific rules based on small subsets of the data. When $n_{\text{min\_split}}$ is large, the model is forced to create more generalized splits that apply to larger portions of the dataset, reducing the risk of overfitting.

Mathematically, the process of regularization in Gradient Boosting can be understood as a way to control the trade-off between bias and variance. Bias refers to the error introduced by simplifying assumptions made by the model, while variance refers to the model's sensitivity to fluctuations in the training data. Regularization techniques aim to reduce variance without significantly increasing bias. This balance can be expressed through the decomposition of the generalization error $E$, which consists of bias, variance, and irreducible error:

$$ E = \text{Bias}^2 + \text{Variance} + \text{Irreducible Error}. $$

Regularization techniques, such as shrinkage, subsampling, and tree constraints, reduce the variance term in this equation, thereby improving the generalization ability of the model. For example, by reducing the learning rate $\eta$, the model’s variance is lowered because each new tree has less impact on the final predictions. Subsampling reduces variance by decreasing the correlation between successive trees, while tree constraints control the complexity of individual trees, further reducing variance.

In practical implementations, finding the right balance between bias and variance requires careful tuning of hyperparameters such as the learning rate, the fraction of subsampled data, the maximum tree depth, and the minimum number of samples required for a split. Cross-validation is often used to determine the optimal values for these parameters, as it provides a reliable estimate of the model’s generalization performance.

In Rust, implementing these regularization techniques involves efficiently managing the training process, which includes tuning hyperparameters and applying constraints on tree growth. Rust’s concurrency and performance capabilities make it well-suited for building scalable Gradient Boosting algorithms that can handle large datasets and numerous iterations while ensuring that the regularization techniques are effectively applied.

In conclusion, regularization techniques are essential to the success of Gradient Boosting models, as they address the tendency of these models to overfit by controlling the trade-off between bias and variance. The learning rate, subsampling, and tree constraints each play a crucial role in reducing variance and promoting generalization. Through careful tuning and application of these techniques, Gradient Boosting can achieve robust performance across a wide range of machine learning tasks, making it a versatile and powerful tool in the field.

In practical terms, implementing regularization techniques in Rust requires an understanding of how these concepts translate into code. Below is a simple implementation of a Gradient Boosting model that incorporates shrinkage, subsampling, and tree constraints. This example leverages the ndarray and serde crates for data manipulation and serialization, respectively.

use ndarray::{Array2, Array1};

use rand::seq::SliceRandom;

use rand::thread_rng;

use std::collections::HashMap;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct GradientBoosting {

learning_rate: f64,

n_estimators: usize,

max_depth: usize,

}

impl GradientBoosting {

fn new(learning_rate: f64, n_estimators: usize, max_depth: usize) -> Self {

GradientBoosting {

learning_rate,

n_estimators,

max_depth,

}

}

fn fit(&self, x: &Array2<f64>, y: &Array1<f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

let mut predictions = Array1::zeros(y.len());

let mut trees = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..self.n_estimators {

// Calculate pseudo-residuals

let residuals = y - &predictions;

// Sample data for subsampling

let sampled_indices = self.subsample_indices(x.nrows());

let sampled_x = self.subsample_2d(x, &sampled_indices);

let sampled_residuals = self.subsample(&residuals, &sampled_indices);

// Fit a tree to the sampled data

let tree = self.fit_tree(&sampled_x, &sampled_residuals);

trees.push(tree);

// Predict using the latest tree

let tree_predictions = self.predict_tree(&sampled_x, &trees.last().unwrap());

// Update only the predictions for the sampled indices

for (&idx, &tree_pred) in sampled_indices.iter().zip(tree_predictions.iter()) {

predictions[idx] += self.learning_rate * tree_pred;

}

}

predictions

}

fn subsample_indices(&self, total: usize) -> Vec<usize> {

let mut indices: Vec<usize> = (0..total).collect();

indices.shuffle(&mut thread_rng());

indices.truncate((total as f64 * 0.8) as usize); // 80% of data

indices

}

fn subsample(&self, data: &Array1<f64>, indices: &[usize]) -> Array1<f64> {

Array1::from_shape_vec(indices.len(), indices.iter().map(|&i| data[i]).collect()).unwrap()

}

fn subsample_2d(&self, data: &Array2<f64>, indices: &[usize]) -> Array2<f64> {

let rows: Vec<_> = indices.iter().map(|&i| data.row(i).to_owned()).collect();

Array2::from_shape_vec((rows.len(), data.ncols()), rows.into_iter().flatten().collect()).unwrap()

}

fn fit_tree(&self, x: &Array2<f64>, y: &Array1<f64>) -> HashMap<String, f64> {

HashMap::new() // Placeholder for the tree model

}

fn predict_tree(&self, x: &Array2<f64>, tree: &HashMap<String, f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

Array1::zeros(x.nrows()) // Placeholder for predictions

}

}

fn main() {

let x = Array2::<f64>::zeros((100, 10)); // 100 samples, 10 features

let y = Array1::<f64>::zeros(100); // 100 target values

let model = GradientBoosting::new(0.1, 100, 3);

let predictions = model.fit(&x, &y);

println!("Predictions: {:?}", predictions);

}

In this example, we define a GradientBoosting struct that encapsulates the model parameters, including the learning rate, number of estimators, and maximum depth of the trees. The fit method is where the training occurs, incorporating subsampling and tree fitting. The subsample_indices method randomly selects a subset of indices from the dataset, which is then used to create a smaller dataset for training each tree.

By implementing these regularization techniques, we can effectively reduce the likelihood of overfitting. The shrinkage factor, controlled by the learning rate, and subsampling contribute to a more generalized model capable of performing well on unseen data. Evaluating the effectiveness of these techniques typically involves cross-validation and assessing the model's performance on test datasets.

In conclusion, understanding and implementing regularization techniques in Gradient Boosting models is crucial for improving model robustness and ensuring generalization. By employing strategies such as shrinkage, subsampling, and tree constraints, we can successfully mitigate overfitting while balancing bias and variance. Through practical implementation in Rust, we can construct effective Gradient Boosting models that leverage these regularization techniques, paving the way for reliable machine learning applications.

16.5. Advanced Gradient Boosting Variants

Gradient Boosting has long been a cornerstone of machine learning due to its capacity to model complex relationships, but advancements like XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost have further refined this technique, making it faster, more efficient, and better suited to modern data challenges. These advanced Gradient Boosting variants introduce several key innovations that extend the performance and scalability of the original algorithm, while maintaining its robustness. Understanding these innovations is crucial for leveraging the full potential of Gradient Boosting, particularly in environments with large-scale datasets, categorical features, and distributed computing requirements. In this section, we will explore the fundamental mathematical and conceptual advancements that these variants bring to Gradient Boosting and present practical considerations for their implementation in Rust.

Traditional Gradient Boosting builds a model sequentially by adding weak learners—typically decision trees—in a stage-wise manner. Each tree is trained to correct the residuals or errors of the preceding trees. While this approach is highly effective in capturing complex patterns in data, it can be computationally expensive, particularly when handling large datasets or high-dimensional feature spaces. XGBoost, short for Extreme Gradient Boosting, improves upon this by introducing several computational and algorithmic optimizations. One of the central innovations in XGBoost is its use of approximate tree learning, which accelerates the process of finding the best splits for each feature by employing a quantile sketch algorithm. Instead of exhaustively evaluating every possible split, the quantile sketch approach allows XGBoost to approximate the best split points, significantly reducing the computational cost while maintaining the quality of the model.

Formally, consider a decision tree model where the goal is to minimize a differentiable loss function $\mathcal{L}(y, F(x))$, where $y$ represents the target variable and $F(x)$ represents the model's prediction. At each stage $m$, a new tree $h_m(x)$ is added to the model to minimize the residual errors of the previous model $F_{m-1}$. The objective function for XGBoost is written as:

$$ \mathcal{L}(y, F_m(x)) = \sum_{i=1}^N \mathcal{L}(y_i, F_{m-1}(x_i) + h_m(x_i)) + \Omega(h_m), $$

where $\Omega(h_m)$ is a regularization term that penalizes the complexity of the tree $h_m(x)$, controlling the model’s capacity and preventing overfitting. XGBoost incorporates both $L_1$(lasso) and $L_2$ (ridge) regularization, allowing for fine-tuned control over the model's complexity. This regularization, coupled with the approximate tree learning strategy, makes XGBoost both robust and computationally efficient, particularly for large datasets.

In addition to regularization, XGBoost introduces a novel sparsity-aware algorithm for handling missing data. Instead of requiring imputation or preprocessing, XGBoost automatically learns the best direction to send missing values during training. This is done by incorporating missing values directly into the tree-building process, ensuring that the model makes optimal use of the available data without introducing biases from manual imputation strategies. This approach to handling missing values is mathematically embedded in the loss minimization process, as XGBoost evaluates the impact of missing data during its optimization routine.

LightGBM, or Light Gradient Boosting Machine, further builds on these ideas by introducing a histogram-based gradient boosting approach, which improves computational efficiency when dealing with large datasets. LightGBM discretizes continuous feature values into discrete bins, creating histograms that approximate the distribution of the data. Formally, let $x \in \mathbb{R}^d$ represent the feature vector, and let $B$ denote the number of bins. For each feature, LightGBM constructs a histogram that maps the continuous feature space into BBB discrete intervals. The tree-building process then operates on these bins, rather than on the raw continuous values, significantly reducing both memory usage and computational time. The histogram-based method ensures that large-scale datasets with high-dimensional feature spaces can be processed efficiently, with complexity reduced from $O(n \log n)$ to $O(B \log B)$, where $n$ is the number of data points and BBB is the number of bins.

In addition to its histogram-based learning, LightGBM introduces Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) and Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB). GOSS selectively samples the data based on the magnitude of the gradient, giving higher weight to instances with larger gradients that are harder to classify correctly. This focuses the learning process on the most informative samples, while reducing the overall computation. EFB, on the other hand, bundles mutually exclusive features—features that are unlikely to appear together—into a single group, further reducing the dimensionality and complexity of the model.

CatBoost, developed by Yandex, addresses one of the persistent challenges in machine learning: handling categorical features. Traditional Gradient Boosting methods typically require extensive preprocessing of categorical data, such as one-hot encoding or label encoding, which can introduce biases or increase the dimensionality of the feature space. CatBoost solves this by using a novel ordered boosting technique, which creates permutations of the dataset to generate predictions in a way that prevents target leakage (i.e., the use of future information for past predictions). Mathematically, CatBoost maintains an ordered version of the dataset, and for each permutation, it generates a new set of splits based on the ordering of the data. This approach ensures that each tree is trained on data that is independent of the future observations, thereby reducing overfitting while handling categorical variables in a more principled way.

The ability of CatBoost to natively handle categorical data is formalized through its use of target statistics, which transforms categorical features by encoding them as a function of the target variable. For each categorical feature $x_{\text{cat}}$, CatBoost computes the mean target value for each category, smoothed with prior statistics to avoid overfitting. The smoothed encoding is given by:

$$ x_{\text{cat\_transformed}} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n_{\text{cat}}} y_i + \alpha \mu}{n_{\text{cat}} + \alpha}, $$

where $y_i$ represents the target values, $n_{\text{cat}}$ is the number of instances of the category, $\alpha$ is a smoothing parameter, and $\mu$ is the overall mean of the target. This transformation allows CatBoost to incorporate categorical features directly into the model, without resorting to high-dimensional one-hot encoding, which can be computationally expensive and prone to overfitting.

All three advanced Gradient Boosting variants—XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost—introduce fundamental innovations that enhance the efficiency and performance of the model, particularly when applied to large-scale or complex datasets. From XGBoost’s approximate tree learning and native handling of missing data, to LightGBM’s histogram-based learning and GOSS, to CatBoost’s ordered boosting and categorical feature handling, these methods push the boundaries of what Gradient Boosting can achieve. Implementing these techniques in Rust would involve leveraging its concurrency capabilities to efficiently parallelize tree-building processes and gradient computations, ensuring that the models scale well even in distributed computing environments.

In conclusion, the advanced variants of Gradient Boosting—XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost—bring significant improvements in terms of computational efficiency, scalability, and robustness. By incorporating innovations such as approximate tree learning, histogram-based learning, and categorical feature handling, these models outperform traditional Gradient Boosting in both speed and accuracy, making them indispensable tools for machine learning practitioners working with large, complex datasets.

To demonstrate the practical implications of these advanced techniques, we will implement XGBoost in Rust using the xgboost crate, enabling us to take advantage of its powerful capabilities. The process begins by setting up our Rust environment and including the necessary dependencies. We will create a simple dataset, train an XGBoost model, and evaluate its performance compared to a traditional Gradient Boosting implementation. Here is a simple illustration of how to get started:

// Add this to your Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

xgboost = "0.3.0" // Check for the latest version

use xgboost::{parameters, dmatrix::DMatrix, booster::Booster};

fn main() {

// training matrix with 5 training examples and 3 features

let x_train = &[1.0, 1.0, 1.0,

1.0, 1.0, 0.0,

1.0, 1.0, 1.0,

0.0, 0.0, 0.0,

1.0, 1.0, 1.0];

let num_rows = 5;

let y_train = &[1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 0.0, 1.0];

// convert training data into XGBoost's matrix format

let mut dtrain = DMatrix::from_dense(x_train, num_rows).unwrap();

// set ground truth labels for the training matrix

dtrain.set_labels(y_train).unwrap();

// test matrix with 1 row

let x_test = &[0.7, 0.9, 0.6];

let num_rows = 1;

let y_test = &[1.0];

let mut dtest = DMatrix::from_dense(x_test, num_rows).unwrap();

dtest.set_labels(y_test).unwrap();

// build overall training parameters

let params = parameters::ParametersBuilder::default().build().unwrap();

// specify datasets to evaluate against during training

let evaluation_sets = &[(&dtrain, "train"), (&dtest, "test")];

// train model, and print evaluation data

let bst = Booster::train(¶ms, &dtrain, 3, evaluation_sets).unwrap();

println!("{:?}", bst.predict(&dtest).unwrap());

}

In this example, we create training and testing datasets in dense format and convert them into XGBoost's DMatrix structure. We then set the training labels and prepare the model's hyperparameters using ParametersBuilder. The model is trained over 3 boosting rounds, with evaluation performed on both the training and test sets. Finally, predictions are generated for the test dataset.

Now, to compare the performance of XGBoost with traditional Gradient Boosting, we can implement a basic Gradient Boosting model using a different library or crate in Rust, such as rustlearn. By training both models on the same dataset, we can evaluate metrics like accuracy, log-loss, and training time, offering insights into the enhancements provided by the advanced variants.

In conclusion, the advanced variants of Gradient Boosting, such as XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost, represent significant advancements over traditional methods. Their innovations in handling missing data, distributed computing capabilities, and efficiency optimizations not only enhance model performance but also streamline the modeling process. By implementing and comparing these models in Rust, we gain valuable exposure to their benefits and can better appreciate the evolution of Gradient Boosting techniques in practical machine learning applications.

16.6. Hyperparameter Tuning in Gradient Boosting

Hyperparameter tuning is a critical component in optimizing the performance of Gradient Boosting models, as it directly impacts their ability to generalize and make accurate predictions on unseen data. In Gradient Boosting, key hyperparameters include the learning rate (denoted as η\\etaη), the depth of the decision trees, and the number of trees in the ensemble. Each of these hyperparameters plays a significant role in the model’s performance, and understanding the mathematical and conceptual implications of their settings is essential for effective tuning.

The learning rate $\eta$, which controls the step size during the optimization process, is one of the most important hyperparameters in Gradient Boosting. Mathematically, the learning rate scales the contribution of each new tree to the overall model. At iteration mmm, the model is updated as:

$$ F_m(x) = F_{m-1}(x) + \eta h_m(x), $$

where $F_{m-1}(x)$ represents the current model and $h_m(x)$ is the new weak learner (typically a decision tree) added at the $m$-th stage. The learning rate $\eta \in (0, 1]$ scales the influence of the new tree on the model’s predictions. A smaller $\eta$ results in more conservative updates, which can help prevent overfitting by making the model’s progression toward minimizing the loss function more gradual. However, smaller learning rates require a greater number of trees to reach an optimal solution, which increases training time and computational cost. Conversely, a larger $\eta$ accelerates convergence but risks overshooting the optimal solution, leading to a poorly generalized model.

The optimal learning rate typically depends on other hyperparameters such as the number of trees and the depth of each tree. Empirical studies have shown that smaller learning rates combined with a larger number of trees can improve performance, as the model is able to fine-tune its predictions at each iteration. However, the trade-off between computational efficiency and model accuracy must be considered carefully.

Tree depth is another crucial hyperparameter, as it governs the complexity of the individual decision trees in the Gradient Boosting ensemble. Each tree in the ensemble attempts to correct the residual errors of the previous model by fitting the data more closely. The depth of the tree controls the number of splits, or decision rules, that can be made to partition the data. Formally, let $d_{\text{max}}$ denote the maximum depth of the tree, and let $N$ be the number of training samples. A tree with depth $d$ can make up to $2^d$ splits, generating up to $2^d$ leaf nodes. Deeper trees have the capacity to capture more complex relationships in the data, which may lead to lower training error. However, deeper trees are also more prone to overfitting, as they can model noise and idiosyncrasies in the training data rather than general patterns.

The trade-off between bias and variance is central to understanding the effect of tree depth. A shallow tree with low depth will likely result in high bias, as it may fail to capture important relationships in the data. Conversely, a tree with excessive depth will have low bias but high variance, as it is sensitive to fluctuations in the training data and is more likely to overfit. Thus, finding the optimal tree depth is crucial for balancing bias and variance, and this is typically achieved through cross-validation.

Another fundamental hyperparameter in Gradient Boosting is the number of trees $M$ in the ensemble. The number of trees directly influences the model’s ability to reduce training error, as each new tree is trained to reduce the residual errors of the previous trees. The residuals $r_{im}$ at iteration mmm are computed as the negative gradient of the loss function with respect to the model’s current predictions:

$$ r_{im} = - \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}(y_i, F_{m-1}(x_i))}{\partial F_{m-1}(x_i)}. $$

The new tree $h_m(x)$ is then trained to approximate these residuals, and the model is updated accordingly. While increasing the number of trees can reduce the training error, it can also lead to overfitting if too many trees are added. The optimal number of trees must therefore balance the trade-off between improving the model’s fit to the training data and maintaining its generalization ability to new data.

Hyperparameter tuning strategies play a key role in efficiently identifying the optimal settings for $\eta$, $d_{\text{max}}$, and $M$. One of the most commonly used methods is grid search, which exhaustively evaluates the model's performance across a predefined grid of hyperparameter values. Although grid search is simple to implement, it can be computationally expensive, particularly when the hyperparameter space is large. Mathematically, if there are nnn hyperparameters and each hyperparameter can take $k$ different values, the total number of combinations evaluated by grid search is $k^n$. This exponential growth in the search space makes grid search inefficient for models with many hyperparameters.

Random search offers an alternative that can often be more efficient in practice. Instead of exhaustively searching the hyperparameter space, random search samples hyperparameter combinations from a probability distribution. The key insight behind random search is that not all hyperparameters have an equally significant impact on the model’s performance. In fact, empirical studies have shown that randomly sampling hyperparameter combinations often leads to better performance in less time, as random search is more likely to explore regions of the hyperparameter space that contain high-performing combinations. Mathematically, random search reduces the computational complexity by limiting the number of hyperparameter combinations evaluated, while still providing a good approximation of the optimal settings.

In modern machine learning, Bayesian optimization has gained popularity as an advanced hyperparameter tuning strategy. Bayesian optimization models the hyperparameter space as a probabilistic function and iteratively selects hyperparameter combinations that are expected to yield the best performance based on previous evaluations. This method employs Gaussian processes to model the relationship between the hyperparameters and the model’s performance, allowing for a more intelligent exploration of the hyperparameter space.

In practical terms, implementing hyperparameter tuning for Gradient Boosting models in Rust involves defining the search space for each hyperparameter, training the model iteratively, and evaluating its performance using cross-validation. Rust’s performance and concurrency capabilities make it well-suited for handling large-scale hyperparameter optimization tasks, particularly when using advanced techniques such as Bayesian optimization, which require efficient computation of probabilistic models.

In conclusion, hyperparameter tuning is a critical aspect of optimizing Gradient Boosting models, as the choice of hyperparameters such as the learning rate, tree depth, and number of trees directly affects the model’s performance and generalization. Effective tuning requires a careful balance between model complexity and computational efficiency, and strategies such as grid search, random search, and Bayesian optimization provide different approaches to navigating the hyperparameter space. By tuning these hyperparameters effectively, it is possible to significantly improve the accuracy and robustness of Gradient Boosting models, making them powerful tools for a wide range of machine learning applications.

To illustrate these concepts in practice, we can implement a hyperparameter tuning process in Rust. The following example demonstrates a simple grid search for tuning hyperparameters of a Gradient Boosting model using a synthetic dataset.

use std::time::Instant;

use ndarray::Array2;

use some_crate::gradient_boosting::{GradientBoostingRegressor, GradientBoostingParams}; // Hypothetical crate

fn main() {

// Generate synthetic data

let x: Array2<f64> = generate_synthetic_data(); // Function to generate synthetic data

let y: Vec<f64> = generate_target_data(); // Function to generate target values

// Define hyperparameter grid

let learning_rates = vec![0.01, 0.05, 0.1];

let tree_depths = vec![3, 5, 7];

let num_trees = vec![50, 100, 150];

let mut best_score = f64::MAX;

let mut best_params = GradientBoostingParams::default();

// Start grid search

for &lr in &learning_rates {

for &depth in &tree_depths {

for &ntrees in &num_trees {

let params = GradientBoostingParams {

learning_rate: lr,

max_depth: depth,

n_estimators: ntrees,

};

let start = Instant::now();

let model = GradientBoostingRegressor::fit(&x, &y, ¶ms).unwrap();

let score = model.score(&x, &y).unwrap(); // Hypothetical scoring function

let duration = start.elapsed();

println!("Evaluated params: {:?}, Score: {}, Time: {:?}", params, score, duration);

if score < best_score {

best_score = score;

best_params = params.clone();

}

}

}

}

println!("Best Score: {}, with parameters: {:?}", best_score, best_params);

}

// Function stubs for generating synthetic data

fn generate_synthetic_data() -> Array2<f64> {

// Implementation for generating synthetic features

}

fn generate_target_data() -> Vec<f64> {

// Implementation for generating synthetic target values

}

In this example, we first generate a synthetic dataset and define a grid of hyperparameters to search through. The grid search iterates over each combination of hyperparameters, fitting the Gradient Boosting model and evaluating its score. The model's performance is assessed using a hypothetical scoring function, and the best parameters are tracked throughout the process. The timing of each evaluation is also recorded, providing insights into the computational cost of different hyperparameter settings.

In practice, you may want to consider more sophisticated approaches for hyperparameter tuning, such as using libraries that implement Bayesian optimization or even leveraging parallel processing to expedite the search process. Additionally, cross-validation techniques can be employed to ensure that the model's performance is evaluated on a more robust basis, minimizing the risk of overfitting on the training data. Hyperparameter tuning, when executed thoughtfully, can lead to significant improvements in the performance of Gradient Boosting models, ultimately resulting in more accurate and reliable predictions in real-world applications.

16.7. Applications of Gradient Boosting

Gradient Boosting has established itself as one of the most potent and widely adopted techniques in machine learning, particularly for structured data, due to its ability to construct highly accurate predictive models from weak learners. This versatility makes it a preferred choice across a broad range of industries, from finance and healthcare to marketing, where the ability to capture complex relationships in data is critical. In this section, we explore the diverse applications of Gradient Boosting across these fields, examine its underlying conceptual framework, and present practical implementation strategies using Rust to maximize performance and scalability.

In the financial sector, Gradient Boosting plays a pivotal role in risk assessment, fraud detection, and credit scoring. Financial datasets typically include a combination of continuous and categorical variables, such as income, transaction history, and account types, which contain intricate, non-linear relationships that simpler models may fail to capture. For instance, credit scoring models use Gradient Boosting to predict a borrower’s likelihood of default by analyzing historical data encompassing variables such as credit history, income, employment status, and loan amount. The ability of Gradient Boosting to model these relationships while handling missing data and imbalanced classes makes it particularly suitable for applications like default risk prediction. By refining predictions with each iteration, the model allows financial institutions to make more informed lending decisions and mitigate risk, leading to better portfolio management and customer segmentation.

In healthcare, the potential for Gradient Boosting to improve patient outcomes is profound. The vast amount of data contained in electronic health records (EHRs)—including patient demographics, clinical history, lab results, and treatment plans—can be leveraged to build predictive models that anticipate disease progression, readmission risks, or treatment effectiveness. For instance, a hospital might employ a Gradient Boosting model to predict the probability of patient readmission within 30 days based on clinical variables such as age, comorbidities, previous admissions, and medications prescribed. Such a model allows healthcare providers to identify high-risk patients, enabling them to allocate resources more effectively and implement targeted interventions. The interpretability of Gradient Boosting, particularly when used with techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), further allows medical professionals to understand which variables most significantly impact patient outcomes, offering insights that can improve treatment protocols.

The marketing industry also benefits greatly from the application of Gradient Boosting, particularly in customer behavior analysis, targeted advertising, and churn prediction. In a highly competitive business environment, understanding customer retention and acquisition is paramount. Gradient Boosting models can analyze a wide range of customer data, including demographic information, purchase history, and engagement metrics, to predict customer churn or identify high-value customers who are most likely to respond to specific marketing campaigns. For example, an e-commerce company might use Gradient Boosting to predict which customers are at the highest risk of churning based on their purchase patterns and interaction with the platform. Armed with these predictions, the company can take proactive steps to reduce churn by offering personalized promotions or loyalty programs. Furthermore, by optimizing customer segmentation and targeting, Gradient Boosting enables businesses to enhance their marketing efficiency, boosting return on investment through more precisely targeted promotions.

The conceptual framework of Gradient Boosting is rooted in ensemble learning, where multiple weak learners are combined to form a strong predictive model. At each stage, a new weak learner—typically a decision tree—is trained to correct the residual errors of the ensemble’s previous iteration. This iterative refinement process allows Gradient Boosting to model complex, non-linear relationships in data, making it particularly effective for structured datasets with high-dimensional feature spaces. Mathematically, Gradient Boosting aims to minimize a predefined loss function by adding successive models to the ensemble, each of which is trained on the residuals of the previous models. Formally, let $F_0(x)$ be the initial prediction model (often a constant representing the mean of the target variable in regression tasks). At each iteration mmm, the model is updated as:

$$ F_m(x) = F_{m-1}(x) + \eta h_m(x), $$

where $h_m(x)$ is the weak learner trained on the residuals, and $\eta$ is the learning rate that controls the contribution of the new model to the overall ensemble. The choice of weak learners—typically shallow decision trees—ensures that each learner captures simple patterns in the data, while the ensemble as a whole can model complex interactions. The learning rate η\\etaη plays a critical role in controlling the model’s convergence speed and preventing overfitting.

The flexibility of Gradient Boosting extends beyond its ability to handle different data types; it also allows for the use of various loss functions tailored to specific tasks. In regression tasks, Mean Squared Error (MSE) is commonly used to measure the difference between predicted and actual values, while in classification, log-loss is typically employed to quantify the model’s accuracy. The modular nature of Gradient Boosting makes it adaptable to a wide range of applications by allowing the user to define custom loss functions that suit the unique requirements of their domain.

In practical terms, implementing Gradient Boosting in Rust offers several advantages, particularly for large-scale applications. Rust’s memory safety features and concurrency capabilities make it an ideal choice for building scalable machine learning algorithms that can handle high-dimensional datasets with efficiency and speed. By leveraging libraries such as ndarray for numerical computations and linfa for machine learning tasks, Rust can be used to implement Gradient Boosting models that are not only fast but also memory-efficient, ensuring that the models scale effectively even in resource-constrained environments.

In summary, Gradient Boosting stands as a powerful tool for predictive modeling across various industries, offering flexibility in handling structured data and capturing complex relationships between features. Its applications in finance, healthcare, and marketing demonstrate its versatility and effectiveness in real-world scenarios. The ensemble learning framework of Gradient Boosting, combined with its ability to iteratively improve predictions by correcting residuals, makes it particularly suited to tasks that require high predictive accuracy. Furthermore, the practical implementation of Gradient Boosting in Rust allows for scalable, high-performance models that can be deployed in large-scale machine learning systems.

To illustrate the practical application of Gradient Boosting in Rust, let us consider a credit scoring model. We will utilize the linfa crate, which is a Rust machine learning library, to implement this application. The first step involves setting up the necessary dependencies in the Cargo.toml file.

[dependencies]

linfa = "0.6"

linfa-trees = "0.6"

ndarray = "0.15"

Next, we can write a Rust program that demonstrates how to load a dataset, prepare the features and labels, train a Gradient Boosting model, and evaluate its performance. Here is a basic example:

use std::error::Error;

use std::fs::File;

use csv::ReaderBuilder;

use xgboost::{parameters, DMatrix, Booster};

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

// Load the dataset from a CSV file

let file = File::open("credit_data.csv")?;

let mut reader = ReaderBuilder::new().has_headers(true).from_reader(file);

let mut x_train: Vec<f64> = Vec::new();

let mut y_train: Vec<f64> = Vec::new();

// Read data from the CSV

for result in reader.records() {

let record = result?;

// Assume the last column is the label and the rest are features

for (i, field) in record.iter().enumerate() {

let value: f64 = field.parse()?;

if i == record.len() - 1 {

y_train.push(value); // Last column as label

} else {

x_train.push(value); // Other columns as features

}

}

}

let num_rows = y_train.len();

let num_features = x_train.len() / num_rows;

// Convert training data into XGBoost's matrix format

let mut dtrain = DMatrix::from_dense(&x_train, num_rows)?;

// Set ground truth labels for the training matrix

dtrain.set_labels(&y_train)?;

// Example test data (you can also load this from CSV if needed)

let x_test = &[0.7, 0.9, 0.6]; // Replace with real test data

let num_test_rows = 1;

let y_test = &[1.0]; // Replace with real labels if available

let mut dtest = DMatrix::from_dense(x_test, num_test_rows)?;

dtest.set_labels(y_test)?;

// Specify datasets to evaluate against during training

let evaluation_sets = &[(&dtrain, "train"), (&dtest, "test")];

// Specify overall training setup

let training_params = parameters::TrainingParametersBuilder::default()

.dtrain(&dtrain)

.evaluation_sets(Some(evaluation_sets))

.build()?;

// Train model and print evaluation data

let bst = Booster::train(&training_params)?;

// Get predictions on the test set

let predictions = bst.predict(&dtest)?;

// Print predictions

println!("Predictions: {:?}", predictions);

Ok(())

}

This code snippet outlines the basic steps to implement a Gradient Boosting model in Rust. We first load the credit data, assuming it is in CSV format, and split it into features and labels. We then create a Gradient Boosting model, specifying parameters such as the maximum depth of the trees. Finally, we evaluate the model's accuracy, which provides insights into its predictive performance.

In conclusion, the applications of Gradient Boosting span across multiple fields, showcasing its versatility and robustness as a machine learning technique. Whether it is used in finance for credit scoring, in healthcare for patient outcome predictions, or in marketing for churn predictions, Gradient Boosting consistently delivers strong performance on structured data. As we have seen, implementing such a model in Rust is achievable with the right libraries and understanding, making it a valuable skill for machine learning practitioners looking to leverage Rust's performance and safety features in real-world applications.

16.8. Conclusion

Chapter 16 equips you with a deep understanding of Gradient Boosting Models and their implementation in Rust. By mastering these techniques, you will be able to build powerful, accurate models that excel in both classification and regression tasks, making a significant impact in various machine learning applications.

16.8.1. Further Learning with GenAI

By exploring these questions, you will deepen your knowledge of the theoretical foundations, algorithmic details, and applications of GBMs, preparing you to build and optimize these models for real-world problems.

Explain the fundamental concept of boosting. How does boosting differ from other ensemble methods, and why is it effective for improving model accuracy? Implement a simple boosting algorithm in Rust.

Discuss the role of the gradient descent algorithm in Gradient Boosting. How does gradient descent optimize the loss function in GBMs, and what are the key challenges associated with this approach? Implement gradient descent in Rust and apply it to a GBM.

Analyze the impact of the learning rate in Gradient Boosting. How does the learning rate affect the convergence speed and stability of the model, and what are the trade-offs between using a high or low learning rate? Implement a Gradient Boosting model in Rust with different learning rates and compare the results.

Explore the use of decision trees as base learners in GBMs. Why are decision trees commonly used in Gradient Boosting, and how do their properties make them suitable for this task? Implement decision trees in Rust and use them as base learners in a GBM.