Chapter 19

Model Evaluation and Tuning

"The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existence." — Albert Einstein

Chapter 19 of MLVR provides an in-depth exploration of Model Evaluation and Tuning, critical processes for ensuring that machine learning models are both accurate and generalizable. The chapter begins with an introduction to model evaluation, covering essential concepts like bias, variance, and the bias-variance trade-off. It then delves into specific evaluation metrics for classification and regression tasks, offering practical examples of their implementation in Rust. Cross-validation techniques are discussed in detail, highlighting their role in assessing model generalization and stability. The chapter also covers hyperparameter tuning, providing strategies for optimizing model performance through exhaustive and stochastic search methods. Model selection and ensemble methods are explored, emphasizing how these techniques can enhance model robustness. Finally, the chapter addresses model calibration and interpretability, ensuring that models are reliable and understandable by end-users. By the end of this chapter, readers will have a comprehensive understanding of how to evaluate, tune, and refine machine learning models using Rust.

19.1. Introduction to Model Evaluation

Model evaluation is a pivotal phase in the machine learning workflow, as it systematically assesses how well a model performs on unseen data, beyond the data it was trained on. This process is essential for determining a model’s generalization ability, which refers to how well a model performs on new, unseen data, rather than just memorizing the patterns from the training dataset. In practical machine learning, developing a model that generalizes well is crucial because the goal is not to have the model perform perfectly on the training data but to predict accurately on real-world data that the model has never encountered.

To achieve this, data is typically divided into three subsets: the training set, the validation set, and the test set. Each of these subsets plays a critical role in the model development process, ensuring that the model both fits the training data and generalizes well to new examples.

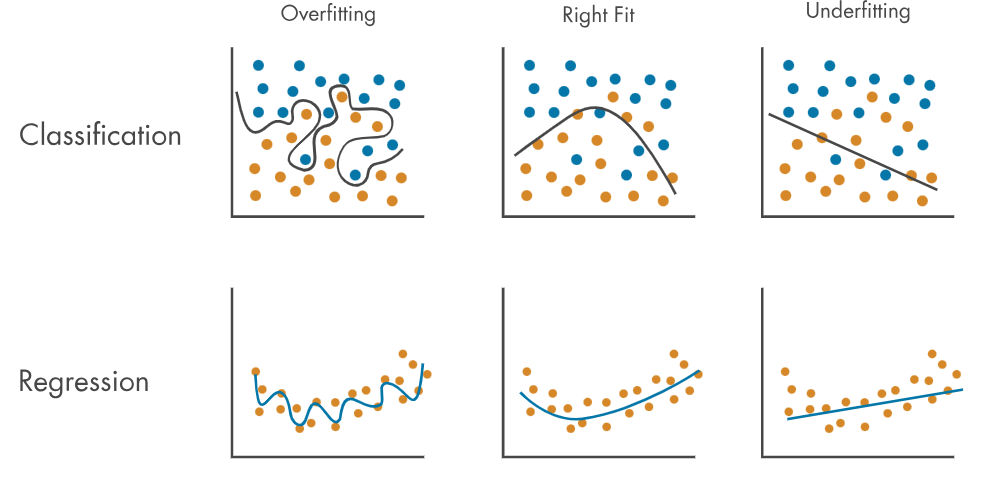

The training set is used to fit the model—that is, to learn the underlying patterns in the data. During this phase, the model iteratively adjusts its internal parameters to minimize some loss function, making predictions that increasingly align with the actual outputs in the training set. While a high performance on the training set is important, it doesn’t guarantee that the model will perform equally well on new data. In fact, if the model achieves very high accuracy on the training set but fails to generalize, it may be a case of overfitting, where the model has learned the noise and specific details of the training data rather than the underlying patterns.

The validation set comes into play to monitor the model’s performance during the development process. It serves as a proxy for unseen data, allowing developers to fine-tune the model's hyperparameters (such as learning rate, model complexity, or regularization parameters) without directly influencing the model's generalization ability. By evaluating the model on the validation set at various stages, we can detect overfitting or underfitting. Overfitting occurs when the model performs significantly better on the training set than on the validation set, indicating that the model may be memorizing the training data rather than learning the general patterns. Underfitting, on the other hand, occurs when the model performs poorly on both the training and validation sets, suggesting that the model is too simplistic to capture the underlying relationships in the data.

Once the model has been trained and validated, it is evaluated on the test set to assess its final generalization performance. The test set acts as completely unseen data and is used to provide an unbiased estimate of the model’s ability to generalize to new examples. Unlike the validation set, the test set is not used during model development or hyperparameter tuning. The performance on the test set gives an indication of how the model will likely perform in real-world applications, where it encounters data that was not available during training or validation.

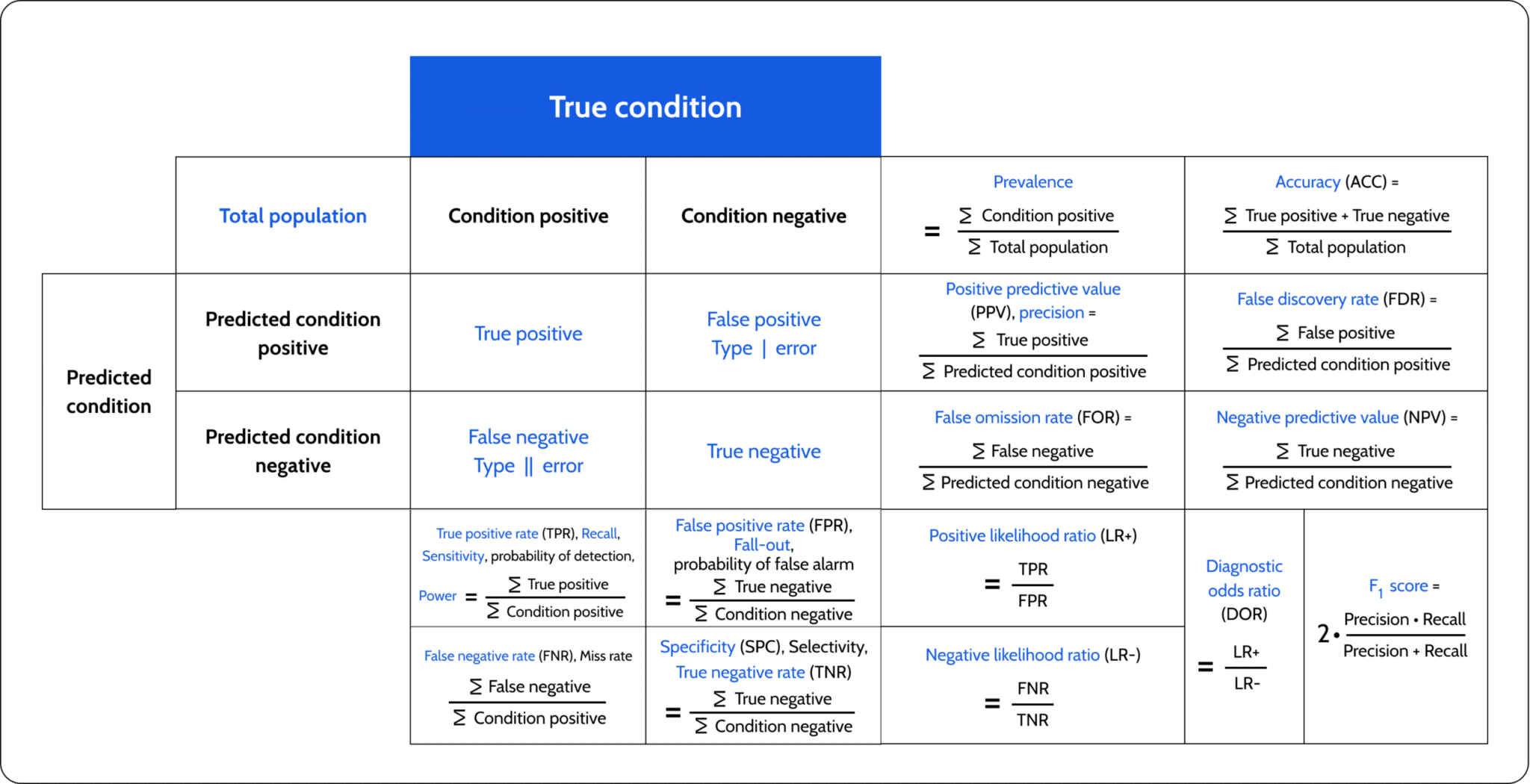

One of the most commonly used metrics to evaluate a model is accuracy, which measures the proportion of correct predictions made by the model out of all predictions. While accuracy can be a useful metric, it doesn’t always provide the full picture of a model’s performance, particularly in cases of imbalanced datasets where one class significantly outweighs others. For instance, in a dataset where 95% of the samples belong to one class, a model that simply predicts the majority class all the time would achieve high accuracy, but it would fail to correctly classify the minority class, leading to poor generalization. To better understand a model's performance, especially in cases of class imbalance, a confusion matrix is often used alongside accuracy. A confusion matrix provides a detailed breakdown of the model’s predictions by showing the number of true positives (correctly predicted positive cases), true negatives (correctly predicted negative cases), false positives (incorrectly predicted positive cases), and false negatives (incorrectly predicted negative cases). This matrix helps identify where the model is making errors and offers a clearer picture of how well it is performing across different classes. For example, in an imbalanced dataset, the confusion matrix might reveal that the model performs well for the majority class but poorly for the minority class, despite a high accuracy score. By using the confusion matrix, other metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score can be calculated, offering a more comprehensive evaluation of model performance.

Figure 1: Confusion matrix (Wikipedia).

Accuracy, while important, must be interpreted alongside other metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score, depending on the specific problem and the dataset's characteristics. These metrics provide additional insights into the model's performance in terms of false positives and false negatives, offering a more complete picture of how well the model generalizes to unseen data.

Generalization is ultimately about balancing the model’s performance on the training data with its ability to perform on new, unseen data. Too much focus on accuracy alone can lead to overfitting, where the model performs well on the training set but poorly on the validation or test set. In contrast, a model that generalizes well may not achieve the highest possible accuracy on the training set, but it will demonstrate strong performance across all datasets, particularly the test set.

Figure 2: Goal of ML model is accuracy and generalization.

Additionally, model generalization can be improved through techniques such as cross-validation, where the model is trained and validated on multiple different splits of the data to ensure that it is not overfitting to a particular subset. This helps the model to learn more general patterns that are applicable to a wider range of unseen data. Other regularization techniques, such as L2 regularization or dropout, also play a critical role in improving generalization by preventing the model from relying too heavily on specific features or patterns in the training data.

Mathematically, let $\mathcal{D} = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^n$ represent the dataset, where $x_i$ are the input features and $y_i$ are the corresponding labels. The dataset $\mathcal{D}$ is typically split into three subsets: the training set $\mathcal{D}_{\text{train}}$, the validation set $\mathcal{D}_{\text{val}}$, and the test set $\mathcal{D}_{\text{test}}$. The training set $\mathcal{D}_{\text{train}}$ is used to fit the model parameters $\theta$, where $\theta$ represents the model's learned weights or coefficients. The model’s performance on the validation set $\mathcal{D}_{\text{val}}$ is used to tune hyperparameters $\lambda$, such as regularization strength, learning rate, or tree depth in ensemble methods. Once the model has been trained and hyperparameters optimized, the test set $\mathcal{D}_{\text{test}}$ is used to evaluate its final performance, yielding an unbiased estimate of how well the model generalizes to new data.

An important concept to understand when evaluating models is the bias-variance trade-off, which helps explain the tension between underfitting and overfitting. Bias refers to the error introduced by approximating a complex real-world problem with a simplified model. A model with high bias is too simplistic and may fail to capture the underlying patterns in the data, leading to underfitting. This can be expressed formally by the bias term in the decomposition of the error function $E[(f(x) - \hat{f}(x))^2]$, where $f(x)$ is the true function and $\hat{f}(x)$ is the model's approximation. On the other hand, variance measures the sensitivity of the model to fluctuations in the training data. High variance indicates that the model is overly complex and fits the noise in the training data, resulting in overfitting. This occurs when the model’s predictions vary significantly for different training datasets drawn from the same distribution.

Mathematically, the mean squared error (MSE) of a model can be decomposed into three terms: bias, variance, and irreducible error. For any input xxx, the expected error can be written as:

$$ E[(f(x) - \hat{f}(x))^2] = \text{Bias}^2[\hat{f}(x)] + \text{Var}[\hat{f}(x)] + \sigma^2, $$

where $\sigma^2$ represents the irreducible error, which arises from noise in the data and cannot be reduced by any model. The bias-variance trade-off is the balancing act between minimizing bias (error due to incorrect assumptions) and minimizing variance (error due to sensitivity to the training data).

One of the most reliable techniques for evaluating model performance and mitigating the bias-variance trade-off is cross-validation. Cross-validation involves partitioning the training data into multiple subsets, or "folds," and then using these folds to validate the model across several training-test splits. The most common form is k-fold cross-validation, where the data is divided into $k$ subsets. For each iteration, one of the $k$ subsets is used as the validation set, while the remaining $k-1$ subsets form the training set. This process is repeated $k$ times, and the final performance metric is computed as the average performance across all folds:

$$ \text{CV score} = \frac{1}{k} \sum_{i=1}^{k} \text{score}_{\text{fold i}}, $$

where $\text{score}_{\text{fold i}}$ represents the performance of the model on the $i$-th fold. This technique provides a more robust estimate of the model's performance because it evaluates the model on multiple train-test splits, reducing the likelihood of overfitting or underfitting to any single subset of the data.

In addition to k-fold cross-validation, there are other forms of cross-validation, such as leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV), where $k$ equals the number of samples, and each sample is used as a validation set exactly once. LOOCV is computationally expensive but provides an even more granular evaluation of the model's performance. Stratified k-fold cross-validation is another variant that ensures each fold maintains the same class distribution as the original dataset, which is particularly useful for imbalanced datasets.

Cross-validation also helps in model selection by providing a mechanism to compare different models or different hyperparameter configurations. For example, when training a regularized model like ridge regression or LASSO, cross-validation can be used to select the optimal regularization parameter $\lambda$ by comparing the cross-validated performance across a range of values for $\lambda$. The optimal hyperparameter $\lambda^*$ is the one that minimizes the average cross-validated error:

$$ \lambda^* = \arg \min_{\lambda} \frac{1}{k} \sum_{i=1}^{k} \mathcal{L}_{\lambda}(\mathbf{X}_{\text{train i}}, \mathbf{y}_{\text{train i}}), $$

where $\mathcal{L}_{\lambda}$ is the loss function parameterized by $\lambda$, and $\mathbf{X}_{\text{train i}}$ and $\mathbf{y}_{\text{train i}}$ are the training data for the $i$-th fold.

In Rust, implementing model evaluation techniques such as cross-validation can be achieved using machine learning libraries like linfa for managing datasets and training models. The implementation involves partitioning the dataset into folds, training the model on different subsets, and evaluating its performance across multiple iterations. Cross-validation in Rust provides the flexibility to experiment with different models and hyperparameters, ensuring that the final model selected is not only accurate but also generalizes well to unseen data.

In summary, model evaluation is a crucial step in ensuring that machine learning models perform well on unseen data. Concepts such as the bias-variance trade-off highlight the challenges associated with balancing model complexity and generalization. Cross-validation provides a reliable framework for evaluating models and selecting optimal hyperparameters, ensuring that models are robust and not overly sensitive to the training data. By integrating these techniques into the machine learning pipeline, practitioners can build models that generalize effectively, thereby increasing their utility in real-world applications.

To put these concepts into practice, we can implement basic model evaluation techniques in Rust. The first step involves splitting our dataset into training, validation, and test sets. This is often done in a stratified manner to maintain the distribution of classes in classification problems. Rust offers libraries like ndarray for numerical computations and rand for random number generation, which can help us with data manipulation and sampling.

Here’s a simple implementation demonstrating how to split a dataset into training, validation, and test sets in Rust. Let's assume we have a dataset represented as a two-dimensional array, where each row is a data point, and we want to split it:

use ndarray;

use rand;

use ndarray::{Array2, Axis};

use rand::seq::SliceRandom;

use rand::thread_rng;

fn split_data(data: &Array2<f32>, train_ratio: f32, val_ratio: f32) -> (Array2<f32>, Array2<f32>, Array2<f32>) {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let mut indices: Vec<usize> = (0..data.nrows()).collect();

indices.shuffle(&mut rng);

let total_samples = data.nrows();

let train_size = (total_samples as f32 * train_ratio).round() as usize;

let val_size = (total_samples as f32 * val_ratio).round() as usize;

let train_indices = &indices[0..train_size];

let val_indices = &indices[train_size..(train_size + val_size)];

let test_indices = &indices[(train_size + val_size)..];

let train_set = data.select(Axis(0), train_indices);

let val_set = data.select(Axis(0), val_indices);

let test_set = data.select(Axis(0), test_indices);

(train_set.to_owned(), val_set.to_owned(), test_set.to_owned())

}

fn main() {

// Example data

let data = Array2::from_shape_vec((10, 3), (0..30).map(|x| x as f32).collect()).unwrap();

let train_ratio = 0.6;

let val_ratio = 0.2;

let (train_set, val_set, test_set) = split_data(&data, train_ratio, val_ratio);

println!("Train Set:\n{:?}", train_set);

println!("Validation Set:\n{:?}", val_set);

println!("Test Set:\n{:?}", test_set);

}

In this code snippet, we begin by importing necessary crates. We then define a function split_data, which takes a dataset and ratios for training and validation sets. The function creates a list of indices, shuffles them randomly, and subsequently slices the indices based on the specified ratios to create training, validation, and test sets. The ndarray crate allows for efficient slicing, making it simple to extract the corresponding subsets of the data.

Once we have our data split, we can move on to evaluating the model using techniques such as cross-validation. Cross-validation is particularly useful for providing a more accurate estimate of a model’s performance by repeatedly splitting the dataset into different training and validation sets. Below is a basic implementation of k-fold cross-validation in Rust:

use ndarray;

use rand;

use rand::Rng;

use ndarray::{Array2, Axis};

use rand::seq::SliceRandom;

use rand::thread_rng;

// Placeholder function to evaluate the model.

// Replace this with your actual model training and evaluation logic.

fn evaluate_model(train_set: &Array2<f32>, val_set: &Array2<f32>) -> f32 {

// In a real use case, you'd train your model using `train_set`

// and validate it using `val_set`. For now, we'll just return

// a dummy score, such as a random float between 0 and 1.

let mut rng = thread_rng();

rng.gen_range(0.0..1.0)

}

fn k_fold_cross_validation(data: &Array2<f32>, k: usize) -> Vec<f32> {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let mut indices: Vec<usize> = (0..data.nrows()).collect();

indices.shuffle(&mut rng);

let fold_size = data.nrows() / k;

let mut scores = Vec::new();

for i in 0..k {

let val_indices: Vec<usize> = indices[i * fold_size..(i + 1) * fold_size].to_vec();

let train_indices: Vec<usize> = indices.iter().cloned().filter(|&x| !val_indices.contains(&x)).collect();

let train_set = data.select(Axis(0), &train_indices);

let val_set = data.select(Axis(0), &val_indices);

// Here, you would train your model using train_set and evaluate it on val_set

let score = evaluate_model(&train_set, &val_set);

scores.push(score);

}

scores

}

fn main() {

// Example data

let data = Array2::from_shape_vec((10, 3), (0..30).map(|x| x as f32).collect()).unwrap();

let k = 5;

let scores = k_fold_cross_validation(&data, k);

println!("Cross-Validation Scores: {:?}", scores);

}

In this function, k_fold_cross_validation, we shuffle the indices of the dataset and divide them into k folds. For each fold, we select validation indices and derive the corresponding training indices by excluding the validation set. The model is then trained on the training set and evaluated on the validation set, with the evaluation scores collected for analysis. The actual model training and evaluation logic would be encapsulated in the evaluate_model function, which would implement your specific model training and scoring methodology.

In summary, model evaluation is a foundational component of machine learning that ensures models not only perform well on training data but also generalize effectively to new, unseen data. By understanding and implementing techniques such as data splitting, the bias-variance trade-off, and cross-validation in Rust, we can build robust and reliable machine learning models. This chapter sets the stage for further exploration into more advanced evaluation metrics and model tuning strategies as we continue our journey through machine learning with Rust.

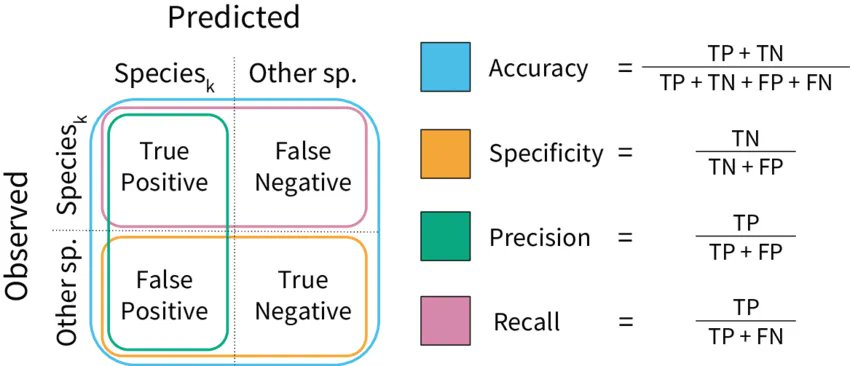

19.2. Evaluation Metrics for Classification

When working with classification models, evaluating their performance is essential to ensure they are both accurate and useful for real-world applications. Several key evaluation metrics help to assess how well a model performs in distinguishing between different classes, and these metrics provide different perspectives on the model's strengths and weaknesses. Some of the most common metrics include accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score. Each metric provides a different view of the model's performance, depending on the context of the problem being solved.

Figure 3: Evaluation metrics for ML classification.

Accuracy is perhaps the simplest and most intuitive metric, representing the proportion of correct predictions (both true positives and true negatives) over the total number of predictions. While accuracy is a good starting point, it can be misleading in cases where the data is imbalanced. For example, in a dataset where 95% of the samples belong to one class, a model that simply predicts the majority class all the time will achieve high accuracy, even if it fails to correctly classify the minority class.

Precision focuses specifically on the positive class and answers the question: "Of all the instances that the model predicted as positive, how many were actually positive?" It is calculated as the ratio of true positives to the sum of true positives and false positives. Precision is particularly useful in scenarios where the cost of false positives is high, such as in spam detection, where mistakenly flagging legitimate emails as spam could be problematic.

Recall, or sensitivity, measures how well the model identifies actual positive cases. It answers the question: "Of all the actual positive instances, how many did the model correctly predict as positive?" Recall is calculated as the ratio of true positives to the sum of true positives and false negatives. Recall is crucial in situations where the cost of missing a positive instance (false negatives) is high, such as in medical diagnoses where failing to detect a disease can have severe consequences.

The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both. It is particularly useful when there is an uneven class distribution or when one metric alone (precision or recall) is not sufficient to describe model performance.

A confusion matrix is a helpful tool to visualize the performance of a classification model. It is a square matrix where each row represents the actual class, and each column represents the predicted class. The diagonal elements indicate the correct predictions, while the off-diagonal elements represent the errors. From the confusion matrix, we can easily calculate the metrics mentioned above.

In practical terms, implementing these metrics in Rust involves creating a module that encapsulates the confusion matrix and provides methods to calculate accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Below is an illustrative example of how this can be done:

/// A struct to represent the confusion matrix for binary classification

#[derive(Debug)]

struct ConfusionMatrix {

true_positive: usize,

true_negative: usize,

false_positive: usize,

false_negative: usize,

}

impl ConfusionMatrix {

/// Create a new confusion matrix

fn new(tp: usize, tn: usize, fp: usize, fn_: usize) -> Self {

ConfusionMatrix {

true_positive: tp,

true_negative: tn,

false_positive: fp,

false_negative: fn_,

}

}

/// Calculate accuracy

fn accuracy(&self) -> f64 {

let total = self.true_positive + self.true_negative + self.false_positive + self.false_negative;

(self.true_positive + self.true_negative) as f64 / total as f64

}

/// Calculate precision

fn precision(&self) -> f64 {

let denominator = self.true_positive + self.false_positive;

if denominator == 0 {

return 0.0;

}

self.true_positive as f64 / denominator as f64

}

/// Calculate recall (sensitivity)

fn recall(&self) -> f64 {

let denominator = self.true_positive + self.false_negative;

if denominator == 0 {

return 0.0;

}

self.true_positive as f64 / denominator as f64

}

/// Calculate F1-score

fn f1_score(&self) -> f64 {

let precision = self.precision();

let recall = self.recall();

if precision + recall == 0.0 {

return 0.0;

}

2.0 * (precision * recall) / (precision + recall)

}

}

fn main() {

// Example usage of the confusion matrix and metric calculations

let cm = ConfusionMatrix::new(50, 40, 10, 5);

println!("Confusion Matrix: {:?}", cm);

println!("Accuracy: {:.2}", cm.accuracy());

println!("Precision: {:.2}", cm.precision());

println!("Recall: {:.2}", cm.recall());

println!("F1-Score: {:.2}", cm.f1_score());

}

In this code, we define a ConfusionMatrix struct that stores the counts of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives. We implement methods to calculate accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score based on these counts. The main function provides an example of how to instantiate a ConfusionMatrix and compute the various metrics.

When utilizing these metrics, it is essential to consider the context of the classification problem. For example, in medical diagnostics, a high recall may be prioritized to ensure that most positive cases are detected, even if it comes at the cost of lower precision. Conversely, in spam detection, a higher precision may be preferred to minimize the occurrence of false positives. Understanding these nuances allows practitioners to make informed decisions about which metrics to optimize during model evaluation and tuning.

In conclusion, the evaluation metrics for classification tasks are fundamental tools that help us gauge the effectiveness of our models. By understanding the strengths and weaknesses of metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the confusion matrix, we can better interpret model performance, particularly in the face of class imbalance. Through practical implementation in Rust, we can easily compute these metrics and compare different models, ultimately guiding us toward more effective machine learning solutions.

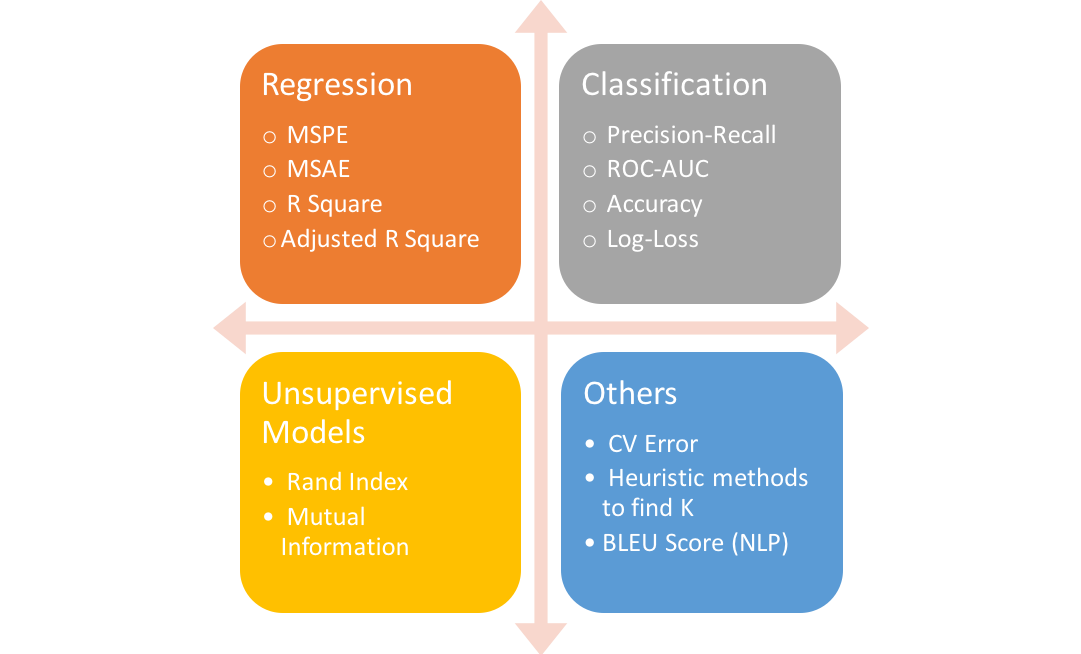

19.3. Evaluation Metrics for Regression

In the realm of machine learning, particularly in regression tasks, evaluation metrics serve as essential tools that allow practitioners to quantify the performance of their models. Understanding these metrics is crucial, as they not only provide insights into how well a model is performing but also guide the tuning and improvement of the model itself. This section delves into some of the fundamental evaluation metrics used in regression, including Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and R-squared. Each of these metrics offers a unique perspective on model performance and is sensitive to different aspects of prediction accuracy.

Figure 4: Evaluation metrics for regression, classification, unsupervised models and others.

Mean Squared Error (MSE) is one of the most commonly used evaluation metrics in regression scenarios. It calculates the average of the squares of the errors—that is, the differences between predicted values and actual values. The formula for MSE is straightforward: it is the sum of the squared differences divided by the number of observations. MSE's sensitivity to outliers is one of its defining characteristics; because it squares the errors, larger errors have a disproportionately high impact on the overall metric, potentially skewing the evaluation if outliers are present.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is simply the square root of MSE. While RMSE carries the same sensitivity to outliers as MSE, it has the added benefit of being expressed in the same units as the target variable, which can make it more interpretable. A lower RMSE value indicates a better fit of the model to the data. RMSE is particularly useful when you want to understand the typical magnitude of the prediction errors; it gives a sense of how far off predictions are, on average, from the actual outcomes.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) offers a different approach to measuring prediction accuracy by calculating the average absolute errors between predicted values and actual values. Unlike MSE and RMSE, MAE does not square the error terms, which means it does not disproportionately amplify the influence of outliers. This property can make MAE a more robust metric when the dataset contains outliers, as it tends to provide a clearer picture of model performance under these conditions. The formula for MAE is the sum of the absolute differences divided by the number of observations, making it easy to compute and interpret.

R-squared, or the coefficient of determination, is another important metric that assesses the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that can be explained by the independent variables in the model. R-squared values range from 0 to 1, where a value closer to 1 indicates that a large proportion of variance is explained by the model, signifying a good fit. However, R-squared has its limitations; it can sometimes give misleading indications of model performance, especially in the presence of outliers or when comparing models with different numbers of predictors.

To illustrate the practical implementation of these metrics in Rust, consider the following code snippet that defines functions to calculate MSE, RMSE, MAE, and R-squared. This implementation assumes that the actual and predicted values are provided as slices of floating-point numbers.

use std::f64;

fn mean_squared_error(actual: &[f64], predicted: &[f64]) -> f64 {

assert_eq!(actual.len(), predicted.len());

let sum_squared_errors: f64 = actual.iter()

.zip(predicted.iter())

.map(|(a, p)| (a - p).powi(2))

.sum();

sum_squared_errors / actual.len() as f64

}

fn root_mean_squared_error(actual: &[f64], predicted: &[f64]) -> f64 {

mean_squared_error(actual, predicted).sqrt()

}

fn mean_absolute_error(actual: &[f64], predicted: &[f64]) -> f64 {

assert_eq!(actual.len(), predicted.len());

let sum_absolute_errors: f64 = actual.iter()

.zip(predicted.iter())

.map(|(a, p)| (a - p).abs())

.sum();

sum_absolute_errors / actual.len() as f64

}

fn r_squared(actual: &[f64], predicted: &[f64]) -> f64 {

assert_eq!(actual.len(), predicted.len());

let mean_actual: f64 = actual.iter().sum::<f64>() / actual.len() as f64;

let ss_total: f64 = actual.iter()

.map(|a| (a - mean_actual).powi(2))

.sum();

let ss_residual: f64 = actual.iter()

.zip(predicted.iter())

.map(|(a, p)| (a - p).powi(2))

.sum();

1.0 - (ss_residual / ss_total)

}

fn main() {

// Example usage

let actual = [3.0, -0.5, 2.0, 7.0];

let predicted = [2.5, 0.0, 2.0, 8.0];

println!("Mean Squared Error: {:.2}", mean_squared_error(&actual, &predicted));

println!("Root Mean Squared Error: {:.2}", root_mean_squared_error(&actual, &predicted));

println!("Mean Absolute Error: {:.2}", mean_absolute_error(&actual, &predicted));

println!("R-Squared: {:.2}", r_squared(&actual, &predicted));

}

In this code, each function takes slices of actual and predicted values, computes the respective metric, and returns the result. For instance, the mean_squared_error function computes the MSE by iterating through the paired actual and predicted values, calculating the squared differences, summing them up, and finally dividing by the number of observations. Similarly, the root_mean_squared_error function simply takes the square root of the MSE. The mean_absolute_error function follows a similar approach but uses absolute differences instead.

To analyze model performance, one can apply these metrics after fitting a regression model. For instance, after training a linear regression model, you could obtain predictions and then compute MSE, RMSE, MAE, and R-squared to evaluate the model's performance. The results will not only reveal how well your model is performing but also provide insights into areas for improvement, such as adjusting model parameters, selecting different features, or even choosing a different modeling approach altogether.

In conclusion, understanding and implementing evaluation metrics for regression tasks in Rust allows practitioners to measure the accuracy of their continuous predictions effectively. By leveraging MSE, RMSE, MAE, and R-squared, one can gain valuable insights into model performance, while recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of each metric in different scenarios. Thus, it is imperative for machine learning practitioners to not only understand these metrics conceptually but also to apply them practically in order to enhance their modeling efforts in Rust.

19.4. Cross-Validation Techniques

In the realm of machine learning, the evaluation of model performance is paramount to ensure that the model can generalize well to unseen data. One of the most effective methods for assessing model generalization is through cross-validation techniques. This section delves into the fundamental ideas surrounding cross-validation, including k-fold cross-validation, stratified cross-validation, and leave-one-out cross-validation, while also exploring their advantages and limitations. Furthermore, we will implement these techniques in Rust, applying them to various models and evaluating their stability and performance.

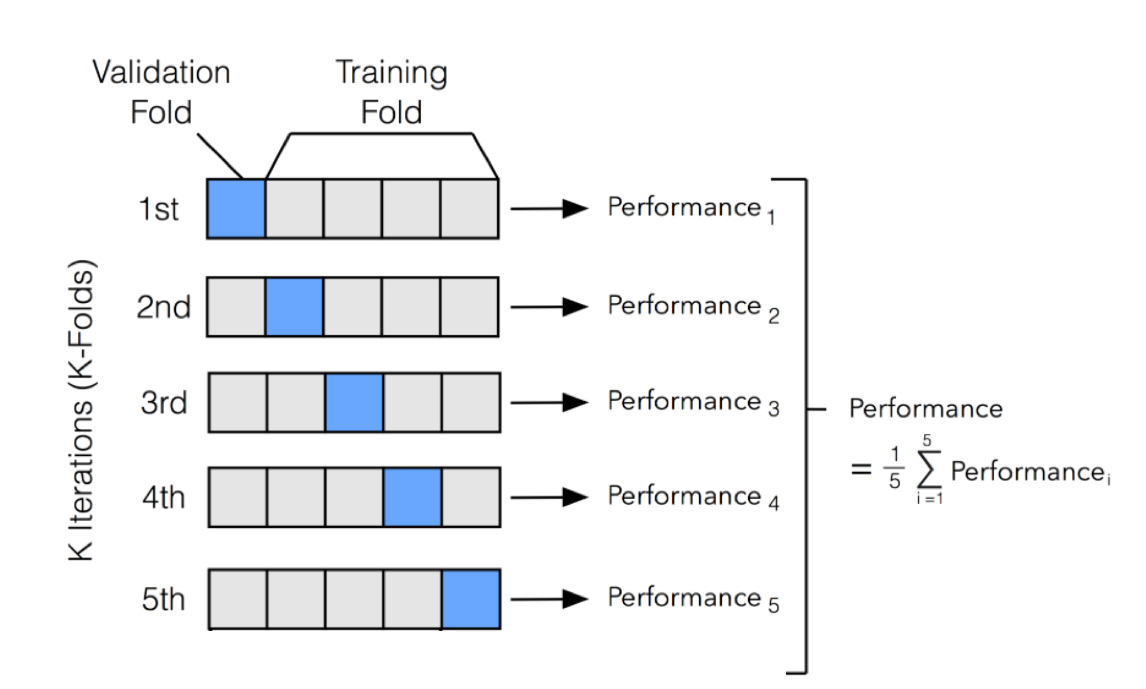

Figure 5: k-fold cross-validation technique.

Cross-validation is a technique that allows us to partition our dataset into subsets to train and test models multiple times, providing a more reliable estimate of a model's performance. The most common form of cross-validation is k-fold cross-validation, where the dataset is divided into k equally sized folds. The model is trained on k-1 folds and tested on the remaining fold, cycling through the folds until each has been used as a testing set. This method helps mitigate the risk of overfitting by ensuring that the model is validated on multiple subsets of the data.

Stratified cross-validation is a variation of k-fold cross-validation that aims to maintain the proportion of classes within each fold. This is particularly important in cases of imbalanced datasets, where some classes are underrepresented. By preserving the class distribution, stratified cross-validation provides a more accurate assessment of the model's ability to predict across all classes. The leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) method takes this a step further, using a single observation from the dataset as the test set while the remaining observations serve as the training set. This technique can be computationally expensive but is beneficial for small datasets, as it maximizes the use of available data for training.

Each of these cross-validation techniques comes with its advantages and limitations. K-fold cross-validation is relatively efficient and provides a good balance between bias and variance, but the choice of k can significantly influence the results. A smaller k might lead to higher variance, while a larger k can increase computation time without substantial performance improvement. Stratified cross-validation addresses issues related to class imbalance, though it may not always be applicable, particularly in continuous target variables. LOOCV provides the most rigorous evaluation by utilizing almost all data for training, but it can be computationally prohibitive for larger datasets, as it requires training the model as many times as there are samples.

To illustrate the practical implementation of cross-validation techniques in Rust, we will create a simple linear regression model and apply k-fold cross-validation. We will first define a dataset and then build a function to perform k-fold cross-validation. For this example, we will use a hypothetical dataset containing features and target values.

Here’s how we can set up our Rust environment and implement k-fold cross-validation:

use rand::seq::SliceRandom;

use rand::thread_rng;

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

struct DataPoint {

features: Vec<f64>,

target: f64,

}

fn k_fold_cross_validation(data: &Vec<DataPoint>, k: usize) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let mut shuffled_data = data.clone();

shuffled_data.shuffle(&mut rng);

let fold_size = data.len() / k;

let mut accuracies = Vec::new();

for i in 0..k {

let test_set: Vec<DataPoint> = shuffled_data[i * fold_size..(i + 1) * fold_size].to_vec();

let train_set: Vec<DataPoint> = shuffled_data

.iter()

.enumerate()

.filter(|(j, _)| j < &(i * fold_size) || j >= &((i + 1) * fold_size))

.map(|(_, dp)| dp.clone())

.collect();

let accuracy = train_and_evaluate_model(&train_set, &test_set);

accuracies.push(accuracy);

}

accuracies

}

fn train_and_evaluate_model(_train_set: &Vec<DataPoint>, _test_set: &Vec<DataPoint>) -> f64 {

// A simple linear regression implementation could go here.

// For now, we will return a dummy accuracy.

let dummy_accuracy = 0.75; // Placeholder for actual model evaluation logic

dummy_accuracy

}

fn main() {

let data = vec![

DataPoint { features: vec![1.0, 2.0], target: 1.0 },

DataPoint { features: vec![2.0, 3.0], target: 2.0 },

DataPoint { features: vec![3.0, 4.0], target: 3.0 },

DataPoint { features: vec![4.0, 5.0], target: 4.0 },

];

let k = 4;

let accuracies = k_fold_cross_validation(&data, k);

println!("K-Fold Cross-Validation Accuracies: {:?}", accuracies);

}

In this code snippet, we define a DataPoint struct to encapsulate our dataset's features and target values. The k_fold_cross_validation function shuffles the dataset, divides it into k folds, trains the model on k-1 folds, and evaluates it on the remaining fold. The train_and_evaluate_model function represents where the model training and evaluation would take place, returning a dummy accuracy for demonstration purposes.

By implementing and evaluating cross-validation techniques in Rust, we can gain insight into the model's stability and performance across different subsets of the data. These techniques not only provide a robust framework for assessing model generalization but also guide us in model selection and hyperparameter tuning, ultimately enhancing the reliability of our machine learning solutions.

19.5. Hyperparameter Tuning

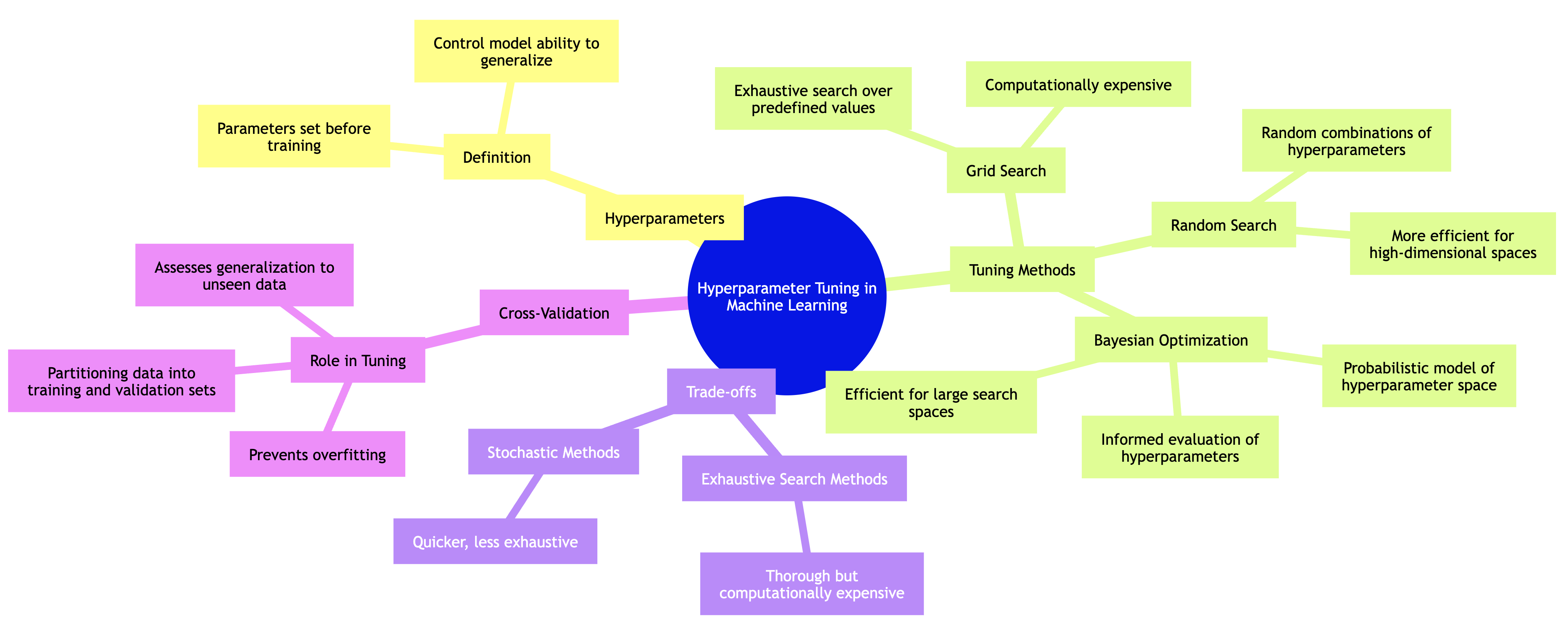

In the realm of machine learning, hyperparameter tuning is a critical step that can significantly influence the performance of a model. Hyperparameters are the parameters that are not learned by the model during training, but rather set prior to the learning process. Their values can dictate the model's ability to generalize to unseen data, making it essential to find the optimal settings. Common methods for hyperparameter tuning include grid search, random search, and Bayesian optimization, each with its own advantages and trade-offs.

Figure 6: Scopes of hyperparamer tuning in Machine Learning.

Grid search is a methodical approach where a predefined set of hyperparameter values is specified for the tuning process. The model is trained and evaluated for every combination of hyperparameters in this grid. While grid search is exhaustive and potentially thorough, it can become computationally expensive, particularly as the number of hyperparameters and their respective ranges increase. On the other hand, random search alleviates some of these concerns by randomly selecting combinations of hyperparameters to evaluate. This stochastic approach can often yield better results in less time compared to grid search, particularly when only a small number of hyperparameters significantly affect model performance.

Bayesian optimization takes a more sophisticated approach to hyperparameter tuning by treating the optimization problem as a probabilistic model. It builds a surrogate model of the objective function and uses it to make informed decisions about which combinations of hyperparameters to evaluate next. This method can converge to optimal hyperparameters more efficiently than both grid and random search, especially in high-dimensional spaces. Understanding these different tuning strategies and their implications helps practitioners choose the best approach for their specific problems.

When undertaking hyperparameter tuning, one must also be cognizant of the trade-offs between exhaustive and stochastic search methods. Exhaustive methods like grid search can guarantee finding the best hyperparameter settings within the specified grid, but they can be limited by time and computational resources. Conversely, stochastic methods like random search and Bayesian optimization may not explore all possible hyperparameter settings but can often identify optimal configurations quicker, especially in cases where the search space is vast.

Cross-validation plays a pivotal role in hyperparameter tuning, as it provides a robust mechanism for estimating model performance. By partitioning the data into training and validation sets multiple times, practitioners can assess how well a model with certain hyperparameters will generalize to unseen data. This process mitigates the risks of overfitting to a particular train-test split, ensuring that the hyperparameter tuning is based on a more representative evaluation of the model's performance.

In practical terms, implementing hyperparameter tuning in Rust involves several steps. We can utilize libraries such as ndarray for efficient numerical computations and linfa, which provides a collection of machine learning algorithms in Rust, including tools for model evaluation and hyperparameter tuning. Here's an example to illustrate how you might implement a grid search hyperparameter tuning process in Rust.

First, we define our model and a function to evaluate its performance based on hyperparameter settings:

use linfa::prelude::*;

use linfa_trees::DecisionTreeClassifier;

use linfa_metrics::{accuracy, Confusion};

fn evaluate_model(params: (usize, usize), features: &ndarray::Array2<f64>, targets: &ndarray::Array1<u32>) -> f64 {

let (max_depth, min_samples_split) = params;

// Create a Decision Tree classifier with specified hyperparameters

let model = DecisionTreeClassifier::params()

.max_depth(max_depth)

.min_samples_split(min_samples_split)

.fit(features, targets)

.expect("Failed to fit the model");

// Perform cross-validation

let cv = linfa::model_selection::cross_validation::KFold::new(5);

let accuracies: Vec<f64> = cv

.split(features)

.iter()

.map(|(train, test)| {

let train_features = features.select(train);

let train_targets = targets.select(train);

let test_features = features.select(test);

let test_targets = targets.select(test);

let model = model.fit(&train_features, &train_targets).unwrap();

let predictions = model.predict(&test_features);

accuracy(&test_targets, &predictions)

})

.collect();

// Return the mean accuracy

accuracies.iter().copied().sum::<f64>() / accuracies.len() as f64

}

In this function, we fit a decision tree model with the given hyperparameters and evaluate its accuracy through cross-validation. Next, we implement the grid search process:

fn grid_search(features: &ndarray::Array2<f64>, targets: &ndarray::Array1<u32>) {

let max_depths = vec![3, 5, 7];

let min_samples_splits = vec![2, 5, 10];

let mut best_accuracy = 0.0;

let mut best_params = (0, 0);

for &max_depth in &max_depths {

for &min_samples_split in &min_samples_splits {

let accuracy = evaluate_model((max_depth, min_samples_split), features, targets);

println!("Evaluated params: max_depth: {}, min_samples_split: {}, accuracy: {}", max_depth, min_samples_split, accuracy);

if accuracy > best_accuracy {

best_accuracy = accuracy;

best_params = (max_depth, min_samples_split);

}

}

}

println!("Best parameters: max_depth: {}, min_samples_split: {}, with accuracy: {}", best_params.0, best_params.1, best_accuracy);

}

In this grid_search function, we iterate through all combinations of hyperparameters defined in max_depths and min_samples_splits, calling the evaluate_model function to assess the accuracy of each combination. After evaluating all combinations, the best-performing hyperparameters are printed.

This implementation demonstrates a straightforward grid search approach to hyperparameter tuning in Rust. By leveraging cross-validation, we ensure that our evaluation is robust and reflective of the model's ability to generalize. As machine learning practitioners continue to explore more complex models and larger datasets, understanding and implementing effective hyperparameter tuning methods becomes increasingly vital. Rust’s performance characteristics and strong type system make it an excellent choice for building efficient machine learning applications, providing the tools and libraries needed to conduct thorough hyperparameter tuning.

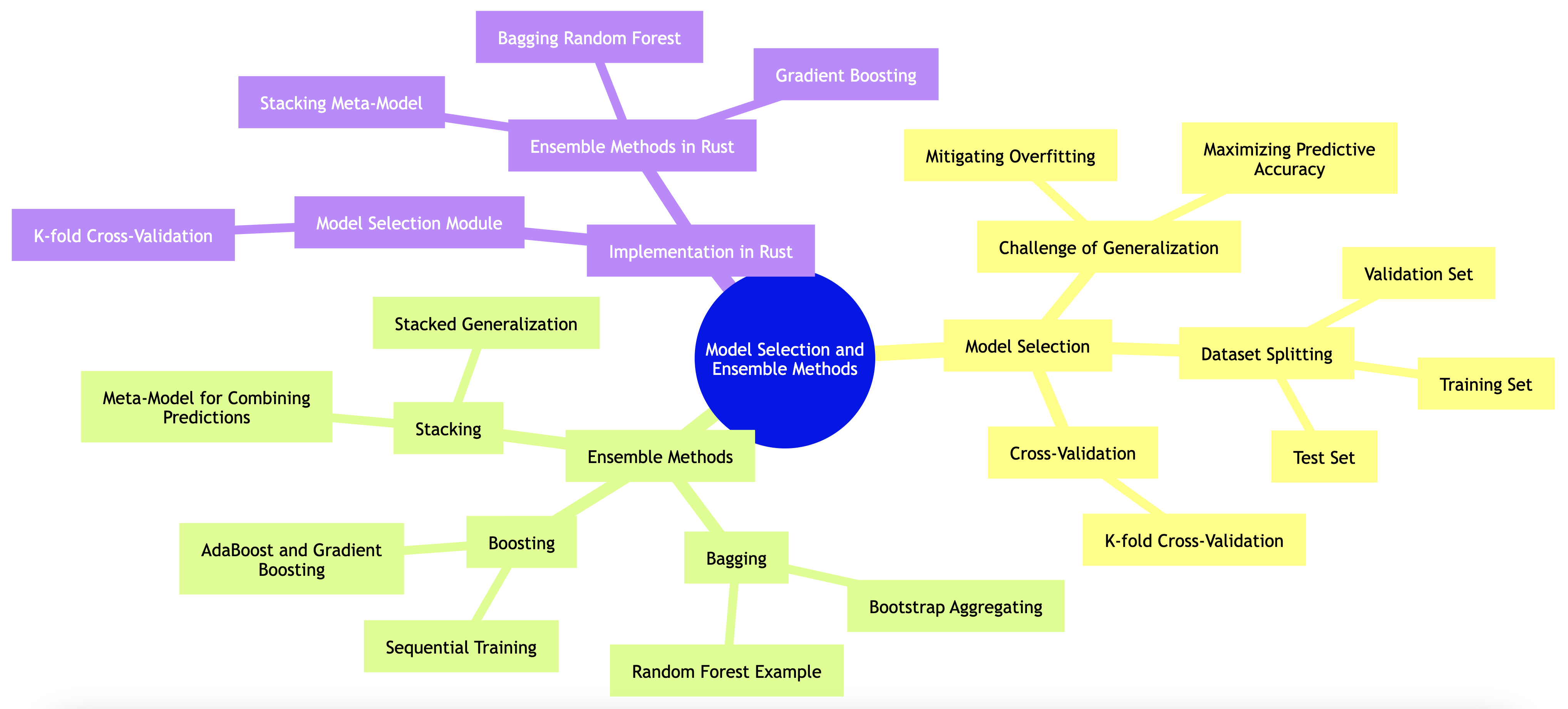

19.6. Model Selection and Ensemble Methods

Model selection and ensemble methods are foundational components in machine learning that directly influence the performance, robustness, and generalization of predictive models. These methods are used to determine which model performs best on a given task and how combining multiple models can lead to more accurate and stable predictions.

Figure 7: Scopes of model selection and ensemble methods.

The process of model selection revolves around choosing the best model from a set of candidate models by assessing their performance on unseen data. A key challenge in machine learning is ensuring that the model selected generalizes well to data it has not encountered during training. This involves mitigating overfitting (where the model learns the noise in the training data rather than the underlying pattern) while still capturing the essential patterns in the dataset.

Typically, model selection is carried out using the training-validation-test split. The dataset is divided into three subsets:

The training set is used to train the model and learn the parameters.

The validation set is used to evaluate the model’s performance and fine-tune its hyperparameters (parameters not learned during training but set prior, like learning rate or number of trees in a forest).

The test set is reserved for the final evaluation of the model, providing an unbiased assessment of how well the model generalizes to new data.

Cross-validation techniques, such as k-fold cross-validation, can also be employed to obtain a more robust estimate of model performance. In this approach, the data is split into k subsets, and the model is trained k times, each time using a different subset as the validation set and the remaining subsets as the training set. This provides a more comprehensive evaluation of the model's generalization ability.

While model selection focuses on identifying the best individual model, ensemble methods aim to improve performance by combining multiple models. The idea is that aggregating predictions from several models can reduce the overall variance and bias, leading to more robust predictions. There are several popular ensemble techniques:

Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating): Bagging works by training multiple models independently using different subsets of the data, created through bootstrapping (sampling with replacement). The predictions of these models are then averaged (for regression tasks) or voted upon (for classification tasks). Random Forest is a prime example of bagging, where multiple decision trees are trained, each on a different random subset of features and data, and their outputs are combined to make a final prediction.

Boosting: Boosting is an iterative technique where models are trained sequentially, with each new model focusing on the errors made by the previous ones. Boosting assigns higher weights to incorrectly predicted samples, allowing subsequent models to focus more on the challenging cases. Popular boosting algorithms include AdaBoost and Gradient Boosting. Boosting is particularly effective in reducing bias and improving predictive accuracy.

Stacking: Stacking, or stacked generalization, involves training multiple models (often of different types) and then combining their predictions using a meta-model. The meta-model is trained to best combine the predictions of the base models, often leading to improved performance. Stacking leverages the diversity of models, where each model may capture different aspects of the data, and the meta-model learns to balance these predictions.

In Rust, we can implement model selection through cross-validation, which involves partitioning the training data into multiple subsets, training the model on some subsets, and validating it on the remaining ones. This process is repeated several times to ensure a robust estimate of model performance. Below is a simple example of how we might implement k-fold cross-validation in Rust:

use ndarray::Array2;

fn k_fold_cross_validation(data: &Array2<f64>, labels: &Array2<f64>, k: usize) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut scores = vec![];

let fold_size = data.nrows() / k;

for i in 0..k {

let validation_start = i * fold_size;

let validation_end = if i == k - 1 { data.nrows() } else { validation_start + fold_size };

let validation_data = data.slice(s![validation_start..validation_end, ..]);

let validation_labels = labels.slice(s![validation_start..validation_end, ..]);

let mut train_data = data.to_owned();

let mut train_labels = labels.to_owned();

train_data.remove_rows(validation_start..validation_end);

train_labels.remove_rows(validation_start..validation_end);

let model = train_model(&train_data, &train_labels);

let score = evaluate_model(&model, &validation_data, &validation_labels);

scores.push(score);

}

scores

}

In this code snippet, we define a function k_fold_cross_validation that accepts a dataset and labels, along with the number of folds k. The function partitions the dataset into k folds and iteratively trains the model while evaluating it on the held-out fold. The performance scores for each fold are collected and returned for further analysis.

As we explore ensemble methods, we uncover a powerful strategy for improving model performance. Ensemble methods work by combining multiple models to create a single, stronger predictive model. The main types of ensemble methods include bagging, boosting, and stacking. Bagging, or Bootstrap Aggregating, involves training multiple instances of the same model on different subsets of the training data, with each model making predictions that are averaged (in regression) or voted (in classification). This reduces variance and helps avoid overfitting.

A classic implementation of bagging in Rust might look like this:

fn bagging(data: &Array2<f64>, labels: &Array2<f64>, n_models: usize) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut predictions = vec![vec![]; n_models];

for _ in 0..n_models {

let bootstrap_sample = sample_with_replacement(data);

let bootstrap_labels = sample_with_replacement(labels);

let model = train_model(&bootstrap_sample, &bootstrap_labels);

let pred = model.predict(data);

for (i, p) in pred.iter().enumerate() {

predictions[i].push(*p);

}

}

predictions.iter().map(|p| average_predictions(p)).collect()

}

In this implementation, the bagging function creates n_models by generating bootstrap samples from the original dataset. Each model is trained on its respective sample, and predictions are collected. The final predictions are obtained by averaging the individual model predictions.

Boosting, on the other hand, is an iterative method that adjusts the weights of training instances based on the performance of the previous models. This means that models that misclassify instances will have their weight increased, thus focusing more on difficult cases in subsequent iterations. A simple boosting algorithm such as AdaBoost can be implemented in Rust as follows:

fn boosting(data: &Array2<f64>, labels: &Array2<f64>, n_models: usize) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut weights = Array2::from_elem((data.nrows(), 1), 1.0 / data.nrows() as f64);

let mut models = vec![];

let mut alphas = vec![];

for _ in 0..n_models {

let model = train_weighted_model(&data, &labels, &weights);

let pred = model.predict(data);

let error = calculate_weighted_error(&pred, labels, &weights);

let alpha = 0.5 * (1.0 - error) / error;

update_weights(&mut weights, &pred, labels, alpha);

models.push(model);

alphas.push(alpha);

}

combine_predictions(&models, &alphas, data)

}

This example shows how boosting can be applied in Rust, where each model is trained with weighted instances and the weights are updated based on model performance. The final predictions are obtained by combining the predictions of all models weighted by their respective alphas.

Lastly, stacking is another powerful ensemble method where different models are trained on the same dataset, and a meta-learner is trained on their predictions to make the final prediction. The meta-learner learns how to best combine the outputs of the base models, often leading to superior performance. Implementing stacking in Rust would require collecting predictions from base models and training a second model on those predictions.

In conclusion, model selection and ensemble methods are fundamental in building robust machine learning systems. Understanding the principles behind these methods allows practitioners to effectively leverage multiple models to enhance performance. Implementing these strategies in Rust not only showcases the language's capabilities in handling numerical computations but also provides a foundation for creating efficient and performant machine learning applications. Through diligent application of model selection techniques and ensemble methods, one can achieve impressive results, ensuring that the models not only fit the data well but also generalize effectively to unseen samples.

19.7. Model Calibration and Interpretability

In the realm of machine learning, particularly when dealing with probabilistic models, the concepts of model calibration and interpretability are of paramount importance. Model calibration refers to the process of adjusting the predictions of a model so that they reflect the true probabilities of outcomes. This is especially crucial in contexts where decisions depend heavily on probability estimates, such as in medical diagnoses or financial predictions. When a model is well-calibrated, its predicted probabilities align closely with the actual outcomes. Conversely, a poorly calibrated model can lead to misguided decisions and erode user trust.

To improve the calibration of a model, several techniques can be employed. Two prominent methods are Platt Scaling and Isotonic Regression. Platt Scaling is a logistic regression model fitted to the scores of the original model, which transforms these scores into calibrated probabilities. On the other hand, Isotonic Regression is a non-parametric approach that works well when the relationship between the predicted scores and the actual probabilities is not necessarily linear. By employing these techniques, practitioners can enhance the reliability of their models, making them more trustworthy in practical applications.

While calibration ensures that the probabilities outputted by a model are reliable, interpretability facilitates the understanding of how these predictions are made. As machine learning models, especially deep learning models, become increasingly complex, understanding the underlying decision-making processes becomes more challenging yet crucial. Interpretability methods such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) provide insights into model behavior by attributing the contributions of individual features to the final predictions.

SHAP values are based on cooperative game theory and provide a unified measure of feature importance. They work by quantifying the impact of each feature on the model's predictions, which helps in understanding not just what factors influence the predictions, but also how they do so. LIME, on the other hand, approximates the model locally by fitting an interpretable model around a specific prediction, allowing users to see how particular features affect the outcome. Both these methods empower users to trust and validate the predictions made by complex models, thereby enhancing user experience and acceptance.

Implementing these calibration and interpretability techniques in Rust requires a thoughtful approach, especially considering Rust’s strengths in performance and safety. For model calibration, one could implement Platt Scaling and Isotonic Regression using the ndarray crate for numerical operations and matrix manipulations. Below is an example of how one might implement Platt Scaling in Rust:

use ndarray;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

use ndarray_stats::interpolation::linear_interpolation;

fn platt_scaling(scores: &Array1<f64>, labels: &Array1<u8>) -> (f64, f64) {

let mut logistic_model = LogisticRegression::new();

logistic_model.fit(scores, labels);

let (a, b) = logistic_model.parameters();

(a, b)

}

fn predict_probabilities(scores: &Array1<f64>, a: f64, b: f64) -> Array1<f64> {

scores.map(|score| 1.0 / (1.0 + (-a * score - b).exp()))

}

In the example above, we define a function for Platt Scaling that fits a logistic model to the scores and labels. The predict_probabilities function then uses the parameters obtained from the logistic regression to transform the scores into calibrated probabilities.

For interpretability, implementing SHAP values in Rust can be more complex but is feasible by leveraging the ndarray library along with some statistical concepts. A rudimentary version of SHAP can be computed by taking subsets of features and evaluating the impact of adding each feature iteratively. Here’s a simple illustration:

fn calculate_shap_values(model: &Model, input: &Array1<f64>, num_samples: usize) -> Array1<f64> {

let mut shap_values = Array1::zeros(input.len());

let baseline_prediction = model.predict(&Array1::zeros(input.len()));

for i in 0..num_samples {

let perturbed_input = perturb_input(input);

let prediction = model.predict(&perturbed_input);

let contribution = prediction - baseline_prediction;

shap_values += contribution / num_samples as f64;

}

shap_values

}

fn perturb_input(input: &Array1<f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

// Logic to perturb the input features

}

In this example, calculate_shap_values estimates the SHAP values by perturbing the input and evaluating how the model's predictions change. This process allows for a better understanding of the influence of each feature.

By incorporating these calibration and interpretability techniques into machine learning models built in Rust, practitioners can significantly enhance their models' reliability and the trust of users in their predictions. The combination of well-calibrated models and interpretable outputs not only fosters a better understanding of the model's decision-making process but also aligns it with the ethical considerations of deploying AI systems in real-world scenarios. Ultimately, this holistic approach to model calibration and interpretability is essential for creating robust, trustworthy machine learning applications that can be confidently used across various domains.

19.8. Conclusion

Chapter 19 equips you with the knowledge and tools necessary to evaluate and tune machine learning models effectively. By mastering these techniques in Rust, you will ensure that your models are accurate, generalizable, and ready for real-world deployment, setting the stage for successful machine learning applications.

19.8.1. Further Learning with GenAI

By exploring these prompts, you will deepen your knowledge of the theoretical foundations, practical applications, and advanced techniques in model evaluation, preparing you to build and optimize robust machine learning models.

Explain the importance of model evaluation in the machine learning pipeline. How does proper evaluation ensure that models are accurate and generalizable, and what are the key steps involved? Implement a basic model evaluation process in Rust.

Discuss the concept of the bias-variance trade-off. How does this trade-off affect model performance, and what strategies can be used to balance bias and variance? Implement a bias-variance analysis in Rust and apply it to a machine learning model.

Analyze the impact of overfitting and underfitting on model performance. How can cross-validation techniques help in detecting and mitigating these issues? Implement k-fold cross-validation in Rust and evaluate its effectiveness in preventing overfitting.

Explore the use of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score in evaluating classification models. How do these metrics complement each other, and when should each be used? Implement these metrics in Rust and compare the performance of different classification models.

Discuss the challenges of evaluating models on imbalanced datasets. How do metrics like ROC-AUC and precision-recall curves provide a more accurate assessment in such scenarios? Implement ROC-AUC and precision-recall curves in Rust for a model trained on an imbalanced dataset.

Analyze the role of regression metrics, such as MSE, RMSE, MAE, and R-squared, in evaluating continuous predictions. How do these metrics differ in their sensitivity to outliers and interpretability? Implement these regression metrics in Rust and apply them to a regression model.

Explore the concept of cross-validation and its variations, such as stratified cross-validation and leave-one-out cross-validation. How do these methods help in assessing model generalization, and what are their advantages and limitations? Implement different cross-validation techniques in Rust and compare their effectiveness.

Discuss the importance of hyperparameter tuning in optimizing model performance. How do methods like grid search, random search, and Bayesian optimization differ in their approach to tuning, and what are their trade-offs? Implement hyperparameter tuning in Rust and optimize a machine learning model.

Analyze the role of ensemble methods in improving model robustness. How do techniques like bagging, boosting, and stacking combine multiple models to enhance performance, and what are the challenges of implementing these methods? Implement an ensemble method in Rust and evaluate its impact on model accuracy.

Explore the concept of model calibration, particularly for probabilistic models. How do calibration techniques like Platt scaling and isotonic regression improve the reliability of predicted probabilities? Implement model calibration in Rust and apply it to a classification model.

Discuss the trade-offs between model complexity and interpretability. How can techniques like SHAP values and LIME be used to make complex models more understandable, and what are the challenges of applying these methods? Implement interpretability techniques in Rust and evaluate their impact on model trustworthiness.

Analyze the impact of cross-validation fold size on model evaluation. How does the choice of k in k-fold cross-validation affect the stability and reliability of the evaluation, and what are the best practices for selecting k? Implement a cross-validation analysis in Rust and experiment with different fold sizes.

Explore the use of learning curves in evaluating model performance. How do learning curves help in diagnosing issues like overfitting or underfitting, and what insights can they provide into model training dynamics? Implement learning curves in Rust and analyze a machine learning model's performance over different training sizes.

Discuss the concept of early stopping in model training. How does early stopping prevent overfitting in iterative algorithms like gradient boosting or neural networks, and what are the best practices for implementing it? Implement early stopping in Rust for a gradient boosting model and evaluate its impact on model generalization.

Analyze the role of validation sets in model evaluation. How does using a validation set help in hyperparameter tuning and model selection, and what are the challenges of properly splitting data into training, validation, and test sets? Implement a validation set approach in Rust and apply it to a complex machine learning model.

Explore the concept of model interpretability in the context of black-box models. How do techniques like SHAP values, LIME, and partial dependence plots provide insights into model behavior, and what are the challenges of interpreting complex models? Implement these interpretability techniques in Rust for a black-box model and evaluate their effectiveness.

Discuss the challenges of evaluating models in the presence of noisy data. How can techniques like robust evaluation metrics or noise-aware cross-validation help in assessing model performance under noisy conditions? Implement noise-aware evaluation techniques in Rust and apply them to a noisy dataset.

Analyze the use of ensemble cross-validation in improving model reliability. How does combining cross-validation with ensemble methods provide a more robust assessment of model performance, and what are the trade-offs of this approach? Implement ensemble cross-validation in Rust and evaluate its impact on model stability.

Explore the future directions of research in model evaluation and tuning. What are the emerging trends and challenges in this field, and how can advances in machine learning contribute to the development of more effective evaluation and tuning techniques? Implement a cutting-edge evaluation or tuning technique in Rust and experiment with its application to a real-world problem.

These prompts are designed to challenge your understanding of Model Evaluation and Tuning and their implementation in Rust. By engaging with these questions, you will explore the theoretical foundations, practical applications, and advanced techniques in model evaluation, equipping you to build and optimize robust machine learning models.

19.8.2. Hands On Practices

These exercises are designed to be challenging and in-depth, requiring you to apply both theoretical knowledge and practical skills in Rust.

Task:

Implement various cross-validation techniques in Rust, including k-fold, stratified, and leave-one-out cross-validation. Apply these techniques to a machine learning model and compare the results in terms of model stability and generalization.

Challenges:

Experiment with different values of k in k-fold cross-validation and analyze their impact on model performance and computational efficiency.

Task:

Implement hyperparameter tuning strategies in Rust, focusing on grid search, random search, and Bayesian optimization. Apply these strategies to a complex machine learning model and optimize its performance.

Challenges:

Compare the efficiency and effectiveness of each tuning strategy, and analyze the trade-offs between exhaustive search methods and stochastic search methods.

Task:

Implement advanced evaluation metrics for classification models in Rust, such as ROC-AUC, precision-recall curves, and F1-score. Apply these metrics to models trained on imbalanced datasets and evaluate their effectiveness in capturing model performance.

Challenges:

Experiment with different threshold settings for classification models and analyze their impact on metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score.

Task:

Implement ensemble methods in Rust, focusing on techniques like bagging, boosting, and stacking. Apply these methods to a machine learning task and evaluate their impact on model accuracy and robustness.

Challenges:

Compare the performance of individual models versus ensemble methods, and analyze the benefits and challenges of using ensembles in different scenarios.

Task:

Implement model calibration techniques in Rust, such as Platt scaling and isotonic regression, to improve the reliability of probabilistic predictions. Apply these techniques to a classification model and evaluate their impact on predicted probabilities.

Challenges:

Experiment with different calibration methods and analyze their effectiveness in improving model confidence and reducing overconfidence in predictions.

By completing these tasks, you will gain hands-on experience with Model Evaluation and Tuning, deepening your understanding of their implementation and application in machine learning.

Comments