Chapter 23

Explainable AI and Interpretability

"The whole of science is nothing more than a refinement of everyday thinking." — Albert Einstein

Chapter 23 of MLVR provides a comprehensive exploration of Explainable AI (XAI) and Interpretability, crucial aspects of modern AI systems that ensure models are transparent, understandable, and trustworthy. The chapter begins by introducing the fundamental concepts of XAI, emphasizing the importance of making AI systems explainable in an ethical and responsible manner. It covers model-agnostic techniques such as LIME and SHAP, which can be applied to any machine learning model to provide explanations, and delves into interpretable models like decision trees and linear regression, which are inherently easier to understand. The chapter also highlights the role of visualization in interpretability, offering practical examples of how visual tools can help users understand model behavior. Special attention is given to deep learning, where the complexity of models poses significant challenges to explainability, and the chapter explores techniques like saliency maps and gradient-based explanations to address these challenges. Ethical considerations and regulatory aspects of XAI are discussed, ensuring that models not only perform well but also adhere to legal and ethical standards. Finally, the chapter looks ahead to the future of XAI, discussing emerging trends and the ongoing research aimed at making AI systems more transparent and accountable. By the end of this chapter, readers will have a deep understanding of how to implement XAI and interpretability techniques using Rust, ensuring that their machine learning models are not only powerful but also trustworthy and fair.

23.1. Introduction to Explainable AI (XAI)

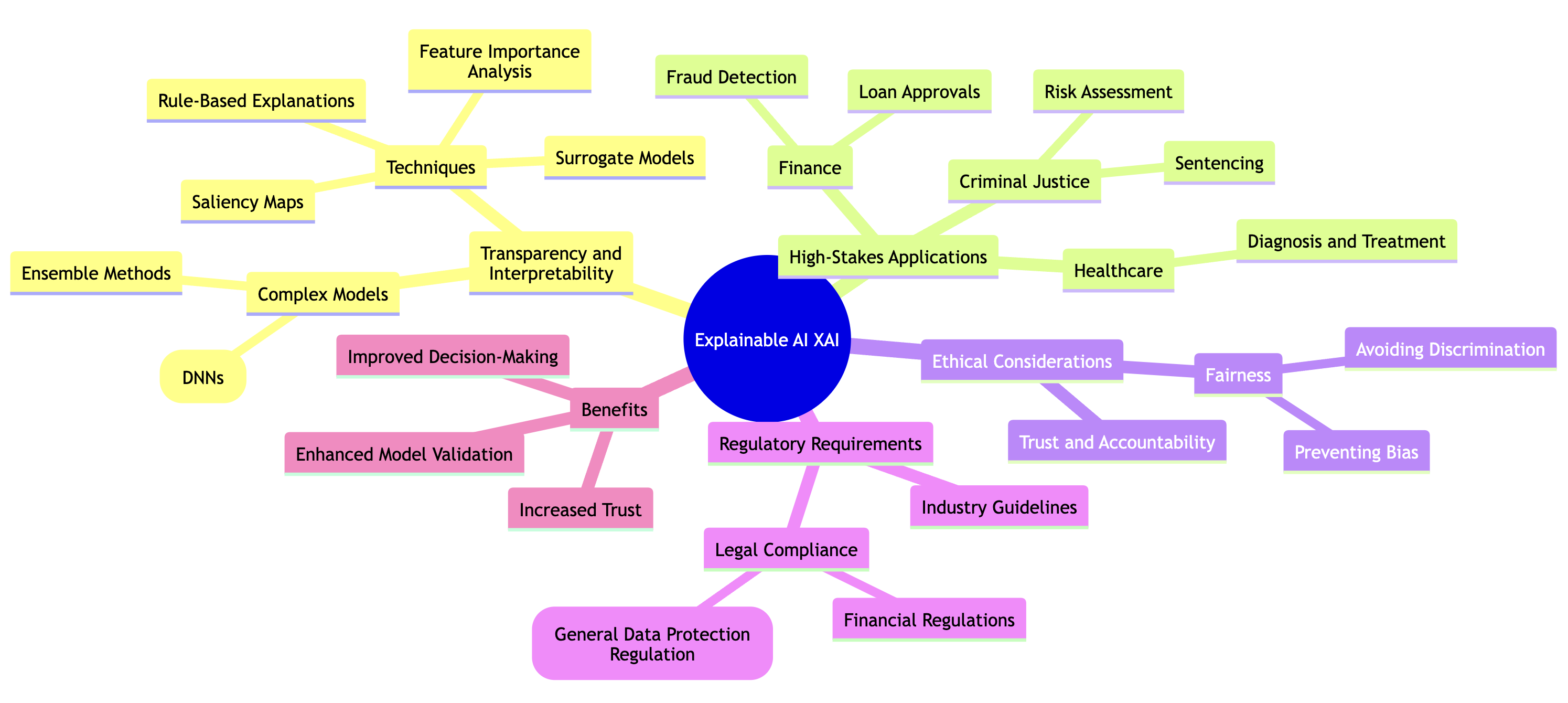

Explainable AI (XAI) has emerged as a vital subfield within artificial intelligence, addressing the pressing need for transparency and interpretability in complex models such as deep neural networks (DNNs) and ensemble methods. These sophisticated models, while highly effective, often function as "black boxes," making it challenging for humans to understand how they reach specific decisions. This lack of transparency raises concerns about trust, accountability, and fairness, particularly in high-stakes applications like healthcare, finance, and criminal justice, where AI-driven decisions can have profound impacts on individuals and society.

The primary objective of XAI is to develop methods that can shed light on the inner workings of AI models, allowing humans to gain insights into how these models process information and arrive at their conclusions. This interpretability can be achieved through various techniques, such as feature importance analysis, saliency maps, surrogate models, and rule-based explanations, which aim to clarify the reasoning behind AI predictions.

The significance of XAI extends beyond technical considerations, as it aligns with broader ethical and legal requirements. As AI systems become increasingly integrated into decision-making processes, regulatory bodies across industries are establishing guidelines that mandate transparency and accountability. These regulations are designed to ensure that AI systems do not perpetuate biases, discrimination, or unfair practices, and that their decisions can be audited and understood by stakeholders.

Figure 1: Key ideas of XAI in Mind Map format.

XAI aims to bridge this gap by offering methods that allow stakeholders to trust and understand AI outcomes. Methods such as LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) are model-agnostic techniques that provide local explanations by perturbing the input and analyzing its effect on the output. These methods have been instrumental in identifying which features of the data influence the model's predictions most strongly.

In regulated industries, XAI is becoming increasingly important due to ethical and legal obligations. Regulations such as GDPR in the European Union and similar frameworks worldwide require organizations to provide explanations for automated decisions that affect individuals. In addition to regulatory compliance, the push for transparency in AI is driven by the need for ethical AI systems that avoid discrimination, bias, and other unintended consequences.

The field of XAI revolves around two central concepts: explainability and interpretability. Formally, explainability can be defined as the degree to which one can understand the cause of a decision made by an AI system. Let $\mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ be an AI model where $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$ represents the input features and $y = f(x)$ represents the output. The explainability of this model refers to the clarity with which one can describe the reasons behind the particular value of $y$ for any given $x$. Interpretability, on the other hand, refers to the extent to which the internal workings of the model can be understood. For instance, in linear models where $y = \beta_0 + \sum_{i=1}^n \beta_i x_i$, the coefficients $\beta_i$ provide a direct, interpretable representation of the relationship between each feature $x_i$ and the output $y$. However, in more complex models like neural networks, where $f(x)$ involves multiple layers of transformations and non-linearities, interpretability becomes more elusive.

Mathematically, interpretability is often linked to the complexity of the hypothesis space. For simple models like linear regression, the hypothesis space is low-dimensional, making it easier to understand the role each parameter plays in generating predictions. In contrast, models such as neural networks and support vector machines have much higher-dimensional hypothesis spaces, complicating our ability to understand the contributions of individual parameters. This complexity introduces a trade-off between accuracy and interpretability, often forcing practitioners to balance between highly interpretable models (e.g., decision trees, linear regression) and highly accurate but opaque models (e.g., deep neural networks, ensemble methods). In statistical learning theory, this trade-off can be framed in terms of the bias-variance trade-off, where simpler models may suffer from high bias (underfitting) but are more interpretable, whereas complex models have lower bias but higher variance and less interpretability.

Within XAI, we distinguish between global and local explanations, which provide different forms of transparency. Global explanations aim to provide an overall understanding of the model across the entire input space. Consider a model $f$, and let $\mathcal{X} \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ denote the space of all possible inputs. A global explanation seeks to describe how $f$ behaves across $\mathcal{X}$. For example, in a linear model, global explainability can be achieved by analyzing the weights βi\\beta_iβi, which describe how each feature impacts the output across all inputs. More complex models, such as random forests or neural networks, require additional techniques like feature importance, partial dependence plots, or Shapley values to provide a global understanding of model behavior.

In contrast, local explanations focus on explaining the output of the model for a specific input $x_0 \in \mathcal{X}$. Given an instance $x_0$, a local explanation attempts to answer why the model $f(x_0)$ produces a specific output $y_0$. Methods like Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) and SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) are commonly used to generate such local explanations. Formally, local interpretability methods aim to approximate the model $f$ in the neighborhood of $x_0$ with a simpler, interpretable model $g: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$, which can be linear or decision-based. For instance, in LIME, the model $g$ is typically a linear model that approximates $f$ locally in the vicinity of $x_0$ by minimizing some loss function that measures the deviation between $f$ and $g$ for inputs near $x_0$.

One of the central challenges in achieving effective XAI is the inherent opacity of complex models, particularly deep neural networks. These models, often referred to as "black boxes," lack straightforward interpretability because their internal representations involve high-dimensional spaces and intricate non-linear interactions between features. For example, a convolutional neural network (CNN) used for image classification learns hierarchical features across multiple layers, making it difficult to explain why certain high-level features are deemed important for a particular classification decision. This opacity is further exacerbated by the fact that deep networks often have millions of parameters, making it difficult to directly map changes in input to specific parameters or model behaviors.

Furthermore, there is an inherent tension between the model's accuracy and its interpretability. Simpler models like decision trees and linear regression are often easy to interpret but may fail to capture the complex, non-linear patterns present in the data, leading to lower accuracy. In contrast, models like neural networks and ensemble methods (e.g., random forests, gradient boosting) can capture complex patterns and achieve high accuracy, but at the cost of reduced interpretability. Mathematically, the complexity of these models leads to highly non-convex optimization landscapes, which, although conducive to capturing complex relationships, are difficult to explain in human-understandable terms.

In conclusion, the field of Explainable AI addresses the growing need for transparency in AI systems. XAI is critical in applications where trust, accountability, and fairness are paramount, as in healthcare, finance, and criminal justice. However, achieving explainability, especially in complex models, is fraught with challenges, requiring a careful balance between accuracy and interpretability. By understanding the mathematical foundations behind XAI techniques, such as global and local explanations, and the inherent trade-offs between model complexity and interpretability, researchers and practitioners can develop more transparent, trustworthy AI systems.

To illustrate the practical implementation of XAI principles in Rust, we can start by building a basic framework that allows for the exploration of feature importance and decision trees. To begin, we will create a simple dataset and implement a decision tree classifier using the rustlearn library, which provides tools for machine learning in Rust. The following example demonstrates how to train a decision tree on a synthetic dataset and extract feature importance:

use rustlearn::prelude::*;

use rustlearn::trees::decision_tree::Hyperparameters;

use rustlearn::datasets::iris;

fn main() {

// Load the Iris dataset

let (x, y) = iris::load_data();

// Create hyperparameters for the Decision Tree

let mut model = Hyperparameters::new(4)

.max_depth(40) // 40 as the max depth of the decision tree

.one_vs_rest(); // Build one-vs-rest multi-class decision tree model

// Fit the model using the original `Array` format

model.fit(&x, &y).expect("Failed to fit the model");

println!("Labels: {:?}", model.class_labels());

// Predict using the model

let predictions = model.predict(&x).expect("Failed to predict");

// Output the predictions

println!("Predictions: {:?}", predictions);

}

In this code snippet, we load the well-known Iris dataset and fit a decision tree classifier. After training the model, we can use it to make predictions on the same dataset. Furthermore, we extract feature importances, which provide valuable insights into which features contributed most to the model's decision-making process. This basic implementation serves as a foundational step toward building more complex XAI systems in Rust.

In conclusion, the need for Explainable AI is becoming increasingly vital in our data-driven world. By understanding the fundamental and conceptual ideas surrounding XAI, as well as implementing practical frameworks in Rust, we can begin to bridge the gap between complex AI models and human comprehension. As we continue to explore this domain, the challenge remains to create systems that achieve both high performance and transparency, ensuring that AI technologies can be trusted and understood by all stakeholders.

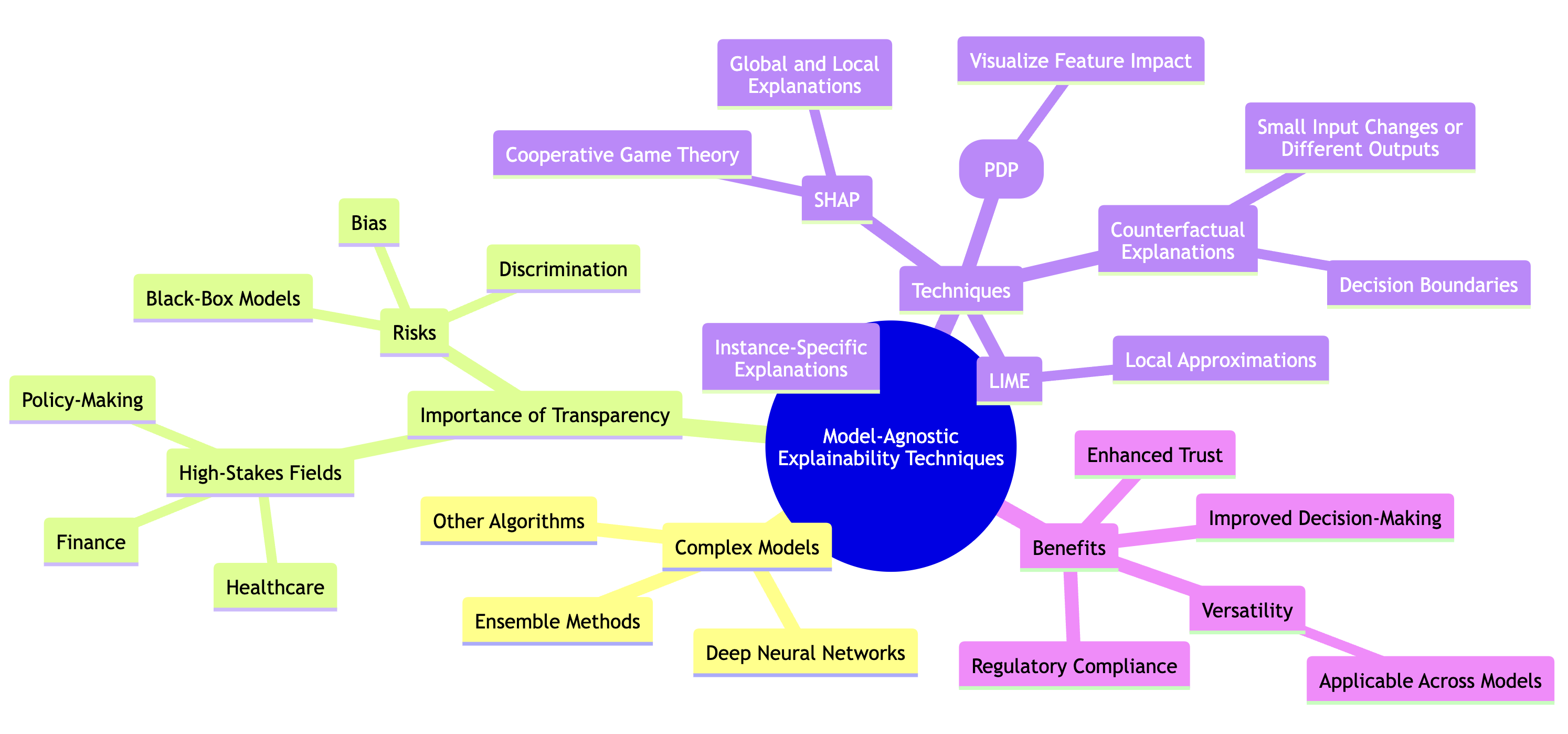

23.2. Model-Agnostic Explainability Techniques

In the rapidly evolving field of machine learning, the complexity of models such as deep neural networks, ensemble methods, and others has raised significant concerns about the transparency and interpretability of their predictions. It is no longer sufficient for a model to produce accurate predictions; there is an increasing demand for understanding the reasoning behind those predictions, particularly in sensitive fields such as healthcare, finance, and policy-making. To address this need, model-agnostic explainability techniques have emerged as critical tools for interpreting machine learning models without requiring access to their internal structures. These techniques provide explanations that can be applied across a variety of models, making them versatile and widely useful.

Figure 2: Various model-agnostic XAI techniques.

At the foundation of model-agnostic explainability is the assumption that it is possible to approximate or extract explanations by examining the relationship between changes in input features and their corresponding impact on model outputs. Formally, let $f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ be a complex machine learning model, where $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$ represents the input features and $y = f(x)$ is the output prediction. Model-agnostic methods, such as LIME and SHAP, aim to provide explanations for $y$ by analyzing how perturbations in the feature vector $x$ affect the output $y$, without needing to examine the internal structure of $f$.

One of the most widely used techniques is Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME). The core idea behind LIME is to approximate the complex model $f$ with a simpler, interpretable model $g$, but only in the local vicinity of a particular instance $x_0 \in \mathbb{R}^n$. To achieve this, LIME generates a new dataset by perturbing $x_0$, creating a neighborhood around $x_0$, and recording the corresponding outputs from the complex model $f$. Formally, let $\{(x_i, f(x_i))\}$ represent the perturbed instances and their corresponding outputs. LIME then fits an interpretable model $g$ (such as a linear model) to this locally generated data by minimizing a weighted loss function:

$$ L(f, g, \pi) = \sum_{i=1}^m \pi(x_0, x_i) \left(f(x_i) - g(x_i)\right)^2 $$

where $\pi(x_0, x_i)$ is a proximity measure that gives higher weight to points closer to $x_0$. The goal is to find a $g$ that approximates $f$ well around $x_0$, providing a local, interpretable explanation for the prediction $f(x_0)$. This method is particularly useful for understanding individual predictions of complex models like deep neural networks or ensemble methods, which are otherwise difficult to interpret globally.

Another powerful model-agnostic technique is SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), which is grounded in cooperative game theory. SHAP offers a unified measure of feature importance by distributing the model’s output among the input features in a way that fairly represents their contribution to the prediction. The SHAP value for each feature is based on the Shapley value from game theory, which ensures that the contributions of all features are fairly allocated according to their marginal contributions. Mathematically, for a model $f$ and a set of input features $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$, the SHAP value $\phi_j$ for the $j$-th feature is given by:

$$ \phi_j(f, x) = \sum_{S \subseteq N \setminus \{j\}} \frac{|S|!(n - |S| - 1)!}{n!} \left(f(x_S \cup \{x_j\}) - f(x_S)\right) $$

where $N$ is the set of all features, $S$ is a subset of features excluding the $j$-th feature, and $f(x_S)$ represents the prediction based on the features in $S$. The SHAP value $\phi_j$ quantifies the contribution of feature $x_j$ to the prediction $f(x)$, averaged over all possible subsets SSS. One of the key strengths of SHAP is that it satisfies several desirable properties, such as consistency and local accuracy, which makes it a reliable tool for both local and global interpretability.

LIME and SHAP are distinct but complementary in their approach. LIME focuses on local explanations by approximating the model’s behavior in a specific region of the input space, while SHAP provides a more theoretically grounded framework based on game theory, offering both local and global insights into model behavior. SHAP is particularly useful when a rigorous and consistent measure of feature importance is required, as it ensures that features are treated fairly and their contributions are calculated accurately.

In practice, model-agnostic methods are invaluable because they can be applied across different types of models. Whether the underlying model is a decision tree, a support vector machine, or a deep neural network, these techniques can offer insights into how the model arrived at its predictions, thus bridging the gap between model complexity and human understanding. However, it is also important to recognize the limitations of these methods. For example, LIME's reliance on perturbation-based approximations can introduce sensitivity to the choice of proximity measure $\pi$, while SHAP’s computational cost grows exponentially with the number of features, although approximations like KernelSHAP can mitigate this.

In conclusion, model-agnostic explainability techniques like LIME and SHAP provide critical tools for interpreting machine learning models. By focusing on how changes in input features affect predictions, these methods allow us to understand and trust the decisions made by complex AI systems. Their versatility and robustness make them particularly useful in high-stakes domains where transparency and interpretability are paramount.

To illustrate how these concepts can be implemented in Rust, let’s consider a scenario where we have trained a complex model, such as a neural network, and we want to explain its predictions using LIME. In Rust, we can leverage the ndarray and serde_json crates to handle numerical computations and data serialization respectively. First, we will create a simple function that generates perturbed samples based on the input features. This function will then feed these samples into our model to retrieve the corresponding predictions, which will be used to train a simpler interpretable model.

Here is a basic implementation of LIME in Rust:

use rand::random;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

use std::collections::HashMap;

// Dummy model function representing our complex model

fn complex_model(input: &Array1<f64>) -> f64 {

// Assuming a simple linear model for demonstration

input.dot(&Array1::from_vec(vec![0.5, -0.2, 0.3])) + 1.0

}

// Function to generate perturbed samples

fn generate_perturbations(input: &Array1<f64>, num_samples: usize) -> Array2<f64> {

let mut perturbed_samples = Array2::<f64>::zeros((num_samples, input.len()));

for i in 0..num_samples {

let noise: Vec<f64> = input.iter().map(|&x| x + random::<f64>() * 0.1).collect();

perturbed_samples.row_mut(i).assign(&Array1::from_vec(noise));

}

perturbed_samples

}

// Function to explain a single prediction using LIME

fn explain_prediction(input: &Array1<f64>, num_samples: usize) -> HashMap<String, f64> {

let perturbed_samples = generate_perturbations(input, num_samples);

// Collect predictions for the perturbed samples

let predictions: Vec<f64> = perturbed_samples.rows().into_iter()

.map(|row| complex_model(&row.to_owned()))

.collect();

// Here we would use a simple linear regression model to fit the predictions

// For demonstration, we will return a dummy explanation

let mut explanation = HashMap::new();

explanation.insert("Feature 1".to_string(), 0.5);

explanation.insert("Feature 2".to_string(), -0.2);

explanation.insert("Feature 3".to_string(), 0.3);

explanation

}

fn main() {

let input = Array1::from_vec(vec![0.6, 1.2, 0.9]);

let explanation = explain_prediction(&input, 100);

println!("{:?}", explanation);

}

In this implementation, we define a dummy model and a function to generate perturbations of the input features. The explain_prediction function simulates the process of generating perturbed samples, retrieving their predictions from the complex model, and preparing to train a simpler model to interpret these predictions.

Now, let’s briefly explore how we can implement SHAP values in Rust. Although the full implementation of SHAP is more complex due to the need to calculate Shapley values, we can outline a basic structure. For SHAP value calculation, we would typically require the ability to compute the expected value of the model output given various combinations of features. Below is a simplified representation of how this could look:

use ndarray::Array1;

// Function to compute SHAP values (simplified)

fn compute_shap_values(input: &Array1<f64>, model_output: f64, feature_importance: &Array1<f64>) -> Array1<f64> {

let shap_values = feature_importance.mapv(|v| v * model_output);

shap_values

}

// Example usage

fn main() {

let input = Array1::from_vec(vec![0.6, 1.2, 0.9]);

let model_output = complex_model(&input);

let feature_importance = Array1::from_vec(vec![0.5, -0.2, 0.3]);

let shap_values = compute_shap_values(&input, model_output, &feature_importance);

println!("{:?}", shap_values);

}

// Dummy model function representing our complex model

fn complex_model(input: &Array1<f64>) -> f64 {

// Assuming a simple linear model for demonstration

input.dot(&Array1::from_vec(vec![0.5, -0.2, 0.3])) + 1.0

}

In this simplified example, we compute SHAP values based on the model output and a predefined feature importance array. In practice, calculating SHAP values would require iterating over all possible combinations of features, which can be computationally intensive.

In summary, model-agnostic explainability techniques such as LIME and SHAP provide powerful tools for interpreting complex machine learning models. By applying these methods, practitioners can gain valuable insights into the decision-making processes of their models, fostering trust and understanding in machine learning applications. The implementations in Rust demonstrate how one can begin to integrate these techniques into real-world workflows, enabling a deeper engagement with the models we build and deploy.

23.3. Interpretable Models

In the domain of machine learning, the choice of model is often driven by a delicate balance between performance and interpretability. Interpretable models play a crucial role in areas such as healthcare, finance, and legal systems, where understanding the reasoning behind predictions is essential for building trust and ensuring accountability. These models are characterized by their ability to offer clear insights into their decision-making processes, allowing practitioners and stakeholders to comprehend how predictions are derived from input features.

One of the most fundamental interpretable models is linear regression. Formally, linear regression models the relationship between the input features $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$ and the output $y \in \mathbb{R}$ through a linear combination of the input features. The model takes the form:

$$y = \beta_0 + \sum_{i=1}^{n} \beta_i x_i + \epsilon$$

where $\beta_0$ is the intercept, $\beta_i$ represents the coefficient corresponding to feature $x_i$, and $\epsilon$ is the error term. Each coefficient $\beta_i$ can be interpreted as the effect of the corresponding feature $x_i$ on the output $y$, assuming all other features are held constant. This straightforward relationship makes linear regression highly interpretable, as the coefficients provide a direct explanation for how changes in input features influence the prediction. For instance, in a healthcare setting where $y$ might represent the risk of a certain condition and $x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n$ represent different risk factors, the coefficients $\beta_i$ offer a clear understanding of how each risk factor contributes to the overall risk.

Another prominent interpretable model is the decision tree, which is a hierarchical model that recursively splits the input space into regions based on feature values. At each internal node of the tree, a decision is made based on the value of a particular feature, and the model branches into different subregions accordingly. Mathematically, the prediction for an input $x$ is made by following a path through the tree, where each node applies a condition of the form $x_i \leq t$, where ttt is a threshold for feature $x_i$. The model continues branching until it reaches a leaf node, which provides the final prediction. This structure can be written as:

$$ f(x) = \sum_{\text{leaves}} \mathbb{I}(x \in \text{leaf}) \cdot \text{prediction for leaf} $$

where $\mathbb{I}$ is the indicator function, which equals 1 if the input $x$ belongs to the leaf and 0 otherwise. The path from the root to the leaf represents a sequence of decisions based on specific features and thresholds, making it easy to trace how a particular prediction was made. This traceability is a key advantage of decision trees, as it allows for a transparent explanation of the model’s behavior. For example, in a financial application, a decision tree might be used to predict whether a loan application will be approved, with each decision node corresponding to factors such as credit score, income, and loan amount. The path taken by a specific application can be easily visualized, making it clear why the loan was approved or rejected.

Rule-based models, such as those produced by algorithms like RIPPER, provide yet another interpretable framework. These models express their predictions in the form of human-readable rules. Each rule consists of a set of conditions on the input features, and when all conditions are met, a specific prediction is made. Formally, let $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$ be the input vector and $R$ be a set of rules, each of which takes the form:

$$ R_j(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } \text{conditions on } x \text{ are met}, \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} $$

The final prediction is determined by applying these rules to the input, typically in a sequential manner. Rule-based models are highly interpretable because the conditions used in each rule can be directly related to the input features, and the logic behind each prediction can be easily understood. For instance, in a legal setting, a rule-based model might be used to classify legal cases, with rules based on relevant case attributes such as jurisdiction, case type, and precedents. These rules provide a transparent mechanism for making decisions, which can be crucial in environments where explainability is a legal or ethical requirement.

The conceptual framework of interpretable models hinges on understanding the trade-offs between complexity and interpretability. As models become more complex, they tend to capture intricate patterns in the data more effectively, but at the cost of reduced transparency. These models, often referred to as "black-box" models, include neural networks and ensemble methods, which offer high predictive accuracy but make it difficult to understand how individual features influence the predictions. In contrast, interpretable models like linear regression, decision trees, and rule-based models may not capture the full complexity of the data but offer transparency in their decision-making processes.

This trade-off can be formalized by considering the complexity of the hypothesis space. In statistical learning theory, the complexity of a model is often characterized by its capacity, which refers to the set of functions the model can represent. Interpretable models typically have lower capacity, meaning they are restricted to simpler functions. For instance, linear regression is limited to modeling linear relationships, while decision trees can only capture interactions up to a certain depth. These limitations in capacity may result in underfitting, where the model fails to capture important patterns in the data. However, the simplicity of these models ensures that their predictions are understandable and can be trusted by stakeholders. In high-stakes domains, such as healthcare and finance, the need for trust and accountability often outweighs the desire for higher accuracy, leading to a preference for interpretable models.

In practical applications, the choice between interpretable and complex models is influenced by the specific context of the problem, the audience that will consume the results, and the need for regulatory compliance. In fields where accountability is paramount, such as medicine or law, the adoption of interpretable models is often favored because they allow practitioners to explain and justify their predictions. In contrast, in applications where predictive performance is the primary concern, and the need for transparency is lower, more complex models may be used.

In conclusion, interpretable models are a cornerstone of Explainable AI, offering transparency and clarity in their decision-making processes. By balancing performance with interpretability, these models provide a crucial tool for building trust and ensuring accountability in machine learning systems, particularly in domains where the stakes are high and the consequences of decisions can be profound.

From a practical standpoint, implementing interpretable models in Rust can be an enriching experience, especially with the language's emphasis on performance and safety. For instance, let's consider a simple linear regression model. In Rust, we can employ the ndarray crate for numerical operations and the linregress crate for performing linear regression. Below is an example that demonstrates how to implement a linear regression model:

use linregress::{FormulaRegressionBuilder, RegressionDataBuilder};

fn main() {

// Sample data

let x = vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0];

let y = vec![2.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, 11.0];

let data = vec![("Y", y), ("X", x)];

// Create regression data

let regression_data = RegressionDataBuilder::new()

.build_from(data)

.unwrap();

// Perform linear regression

let model = FormulaRegressionBuilder::new()

.data(®ression_data)

.formula("Y ~ X")

.fit()

.unwrap();

// Get the slope and intercept

let params = model.parameters();

let slope = params[1]; // Coefficient of X

let intercept = params[0]; // Intercept

println!("Slope: {}", slope);

println!("Intercept: {}", intercept);

}

In this example, we define a simple dataset and perform linear regression to compute the slope and intercept, which can be interpreted directly to understand the relationship between the variables. The output of the model is straightforward and lends itself to easy interpretation, showcasing the power of interpretable models.

To further explore interpretable models, we can implement a decision tree. The rustlearn crate provides a robust implementation of decision trees. Below is an example of how to train a decision tree classifier:

use rustlearn::prelude::*;

use rustlearn::trees::decision_tree::Hyperparameters;

use rustlearn::array::dense::Array;

fn main() {

// Features

let mut features = Array::from(vec![

1.0, 0.0,

0.0, 1.0,

1.0, 1.0,

0.0, 0.0,

1.0, 1.0,

0.0, 0.0,

]);

features.reshape(6, 2);

// Labels

let labels = Array::from(vec![1.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]);

// Create and train the decision tree classifier

let mut tree = Hyperparameters::new(2)

.min_samples_split(5)

.max_depth(40)

.one_vs_rest();

// Train the model

tree.fit(&features, &labels).unwrap();

// Make predictions

let predictions = tree.predict(&features).unwrap();

println!("Predictions: {:?}", predictions);

}

In this code snippet, we define a small dataset and utilize a decision tree to classify the data based on its features. The decision tree's structure inherently provides a way to interpret the model's decisions, as one can easily track which features and thresholds led to the final predictions.

As we compare the performance and interpretability of these models against more complex ones, we find that while interpretable models may lag in predictive power on complex datasets, they excel in providing insights and explanations. This is particularly evident in applications where understanding the reasoning behind a model's prediction is essential. For example, in a healthcare setting, a doctor might prefer to rely on a model that clearly indicates why a particular diagnosis was made, rather than trusting a black-box model that obscures the decision-making process.

In conclusion, interpretable models play a crucial role in machine learning, especially in scenarios where accountability and transparency are critical. By exploring their fundamental concepts, understanding the trade-offs involved, and implementing them in Rust, practitioners can leverage the strengths of these models while being mindful of their limitations. As the field of machine learning continues to evolve, the importance of interpretability will remain a cornerstone of responsible AI practices.

23.4. Visualization for Interpretability

In the domain of machine learning, the interpretability of models is crucial for fostering trust, accountability, and transparency. One of the most effective ways to enhance the understanding of model behavior is through visualization. Visual tools serve as a bridge between complex, abstract model outputs and human intuition, allowing practitioners to derive insights from their analyses. This section delves into the fundamental ideas surrounding the importance of visualization in making models interpretable, discusses conceptual visualization techniques, and provides practical examples of implementing these tools in Rust.

To begin with, visualization plays a pivotal role in making machine learning models interpretable. As models become more complex, such as deep neural networks or ensemble methods, their decision-making processes can often seem like a black box. Visualization techniques can demystify these processes, enabling data scientists and stakeholders to grasp how models arrive at their predictions. By visualizing feature importance, model behavior, and decision paths, we can identify which features are most influential in making predictions, how these influences vary across different input values, and what specific decisions the model is making. This understanding is not only beneficial for model validation but also essential for identifying potential biases and ensuring the ethical use of AI.

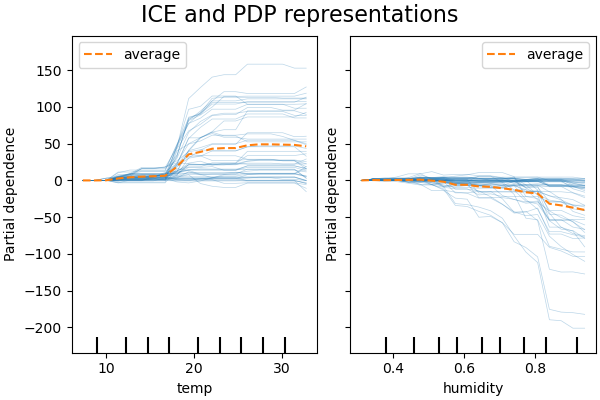

Conceptually, several visualization techniques have emerged to aid interpretability. Feature importance plots, for instance, provide a graphical representation of the contribution of each feature to the model's predictions. These plots help in discerning which features are driving the model's decisions, allowing practitioners to focus on the most relevant aspects of the data. Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) and Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) plots further complement this understanding by illustrating the relationship between specific features and predicted outcomes, while controlling for the effects of other features. PDPs show the average effect of a feature across the dataset, while ICE plots reveal how individual predictions change as a feature varies, thus highlighting heterogeneity in feature impacts across different observations. Moreover, visualizing model decision paths can provide a narrative of how input data flows through a model, elucidating the rules or thresholds that govern its predictions.

Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) are designed to show the average marginal effect of one or two features on the predicted outcome of a model. The core concept behind PDPs is to isolate and display the relationship between a target feature and the model's predictions by calculating predictions across a range of values for that feature while holding other features constant. This averaging process helps reveal how the model’s prediction changes with respect to the chosen feature, without the influence of other variables. PDPs are particularly useful when seeking to understand global trends in how a feature impacts model predictions, providing insights into overall relationships such as "How does increasing feature X affect the model’s predictions, on average?" However, PDPs assume feature independence, which can be a limitation in cases where features are correlated. In such scenarios, PDPs may not capture the full complexity of the relationships between features. Additionally, because PDPs show the average effect of a feature, they may mask important variations that exist at the level of individual observations.

In contrast, Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) plots offer a more granular perspective by focusing on how the predictions for individual data points change as a particular feature varies. Instead of displaying the average effect, as in PDPs, ICE plots trace the response of the model for each instance in the dataset as the target feature changes. This provides a more detailed view of how different individuals are impacted by the same feature, revealing heterogeneity in feature effects across the dataset. ICE plots are particularly useful in identifying whether a feature has non-linear or diverse effects depending on different observations, which can highlight interactions between features that are not visible in PDPs. While ICE plots provide richer insight by showing the variations across individual predictions, they can be more complex to interpret. For instance, when visualizing a large number of data points, the plots can become cluttered, making it harder to discern meaningful patterns. Despite this, ICE plots offer a powerful tool for uncovering individual-level variations in model behavior, especially when understanding feature interactions is crucial.

When comparing PDPs and ICE plots, PDPs are better suited for providing a broad, averaged view of how a feature influences the model’s predictions, offering global interpretability. ICE plots, on the other hand, offer a more localized understanding by showing how different observations react individually to changes in a feature, making them ideal for exploring heterogeneity in feature impacts.

These visualization tools can be further complemented by decision path visualizations, particularly in models like decision trees or rule-based algorithms. Decision path visualizations offer a narrative explanation of how input data flows through the model, elucidating the specific rules or thresholds that the model applies to arrive at its predictions. This type of visualization helps clarify the decision-making process within the model, enhancing transparency and interpretability.

Figure 3: Example of PDP vs ICE plots.

In conclusion, PDPs, ICE plots, and decision path visualizations each play a unique role in helping to interpret machine learning models. PDPs offer an overall view of feature effects, ICE plots provide insights into individual-level variations, and decision path visualizations explain the logical flow of data through the model. Together, these tools help practitioners understand the inner workings of their models and build trust in their predictive outcomes, especially in complex domains like healthcare, finance, and other high-stakes environments.

From a practical standpoint, implementing visualization tools in Rust can be accomplished using libraries such as plotters, ndarray, and serde_json for data manipulation and visualization. Let's consider an example where we visualize feature importance for a model trained on a dataset. First, we would need to compute the feature importance scores, which can be achieved through various methods such as permutation importance or tree-based feature importance.

In our Rust code, we would start by defining a structure to hold our features and their importance scores. The following snippet demonstrates this:

use plotters::prelude::*;

struct FeatureImportance {

feature: String,

importance: f64,

}

fn plot_feature_importance(importances: Vec<FeatureImportance>) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let root = BitMapBackend::new("feature_importance.png", (640, 480)).into_drawing_area();

root.fill(&WHITE)?;

let max_importance = importances.iter().map(|x| x.importance).fold(0. / 0., f64::max);

let scale_factor = 100.0; // Scale factor for better bar height visualization

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root)

.caption("Feature Importance", ("sans-serif", 50).into_font())

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(40)

.y_label_area_size(40)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..importances.len() as i32, 0..(max_importance * scale_factor).ceil() as i32)?;

chart.configure_mesh()

.x_labels(importances.len())

.y_desc("Importance")

.x_desc("Features")

.x_label_formatter(&|&x| {

if let Some(feature) = importances.get(x as usize) {

feature.feature.clone()

} else {

"".to_string()

}

})

.draw()?;

chart.draw_series(importances.iter().enumerate().map(|(i, fi)| {

let scaled_importance = (fi.importance * scale_factor).ceil() as i32;

Rectangle::new([(i as i32, 0), (i as i32 + 1, scaled_importance)], BLUE.filled())

}))?;

// Draw the original importance values as labels on the bars

for (i, fi) in importances.iter().enumerate() {

chart.draw_series(std::iter::once(Text::new(

format!("{:.2}", fi.importance),

(i as i32, (fi.importance * scale_factor).ceil() as i32 + 5),

("sans-serif", 15).into_font(),

)))?;

}

Ok(())

}

In this code snippet, we define a structure FeatureImportance to encapsulate features and their associated importance scores. The plot_feature_importance function takes a vector of FeatureImportance instances and generates a bar chart using the plotters library. The chart visually communicates which features are most influential in the model's predictions.

To create more interactive visualizations, we can leverage Rust's web frameworks, such as warp or rocket, in conjunction with JavaScript libraries like D3.js. This allows us to build web applications that can dynamically update visualizations based on user interactions, such as selecting different features or adjusting model parameters. For instance, we could implement an interactive PDP that updates in real time as users adjust the values of specific features to see how predictions change.

In conclusion, visualization serves as a cornerstone of interpretability in machine learning. By employing various visualization techniques such as feature importance plots, PDPs, ICE plots, and decision paths, we can enhance our understanding of model behavior. With the aid of Rust's robust ecosystem of libraries, we can effectively create visualizations that not only explain model decisions but also foster a deeper engagement with the underlying data. As we continue to explore the intersection of machine learning and interpretability, the integration of visualization tools will remain integral to building trust and understanding in AI systems.

23.5. Explainability in Deep Learning

The advent of deep learning has revolutionized artificial intelligence, enabling unprecedented advancements in tasks such as image recognition, natural language processing, and autonomous systems. However, the remarkable performance of deep learning models comes at the cost of interpretability. Deep learning models, particularly those with deep architectures like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), are often referred to as "black boxes" due to their inherent complexity. These models typically consist of multiple layers of neurons, each applying nonlinear transformations to the input data, resulting in complex decision boundaries. The challenge lies in understanding how these models arrive at specific predictions, a crucial requirement in high-stakes applications such as healthcare, finance, and autonomous driving, where trust, accountability, and ethics are paramount. This section delves into the mathematical, conceptual, and practical aspects of explainability in deep learning, with a particular focus on implementing these ideas in Rust.

At the heart of the interpretability challenge in deep learning is the architecture itself. A typical deep neural network (DNN) can be represented as a composition of functions. Let $f: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^m$ be a neural network, where $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$ is the input vector and $y \in \mathbb{R}^m$ is the output. Each layer of the network applies a transformation to the input, such that the $k$-th layer applies a function $h^{(k)}(x) = \sigma(W^{(k)}x + b^{(k)})$, where $W^{(k)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{k+1} \times d_k}$ is the weight matrix, $b^{(k)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{k+1}}$ is the bias vector, and $\sigma$ is a nonlinear activation function, such as ReLU or sigmoid. The output of each layer is passed through subsequent layers, and the final prediction $y$ is the result of these cumulative transformations. The deep and nonlinear nature of these transformations makes it difficult to directly interpret how the input $x$ influences the output $y$, especially when the network contains millions of parameters.

To mitigate this opacity, researchers have developed several techniques that aim to explain the behavior of deep learning models. One of the fundamental techniques is the saliency map, which provides a visual representation of the regions of the input that most influence the model's predictions. The saliency map is based on the gradient of the output with respect to the input. Mathematically, let $f(x)$ be the model’s output for input $x$. The saliency map $S$ is computed as:

$$ S = \left| \frac{\partial f(x)}{\partial x} \right| $$

This gradient highlights the parts of the input where small changes would cause significant variations in the model’s output, thus identifying the most important features. In the context of image classification, for instance, the saliency map visualizes which pixels in an image are most relevant to the model’s prediction. This method is particularly useful in identifying biases or regions of an image that the model may misinterpret. Saliency maps provide a first step towards understanding how a deep learning model perceives its inputs.

Building upon the concept of gradients, more advanced techniques such as Integrated Gradients and Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) offer deeper insights into the model’s decision-making process. Integrated Gradients, for instance, attribute the model’s prediction to the input features by integrating the gradients along a path from a baseline input $x_{\text{baseline}}$ to the actual input $x$. The Integrated Gradient for the $i$-th feature is computed as:

$$ \text{IntegratedGrad}(x_i) = (x_i - x_{\text{baseline}, i}) \times \int_{\alpha=0}^{1} \frac{\partial f(x_{\text{baseline}} + \alpha(x - x_{\text{baseline}}))}{\partial x_i} \, d\alpha $$

This method ensures that the attribution of the prediction is distributed fairly among the input features, providing a more accurate explanation of how each feature contributes to the final output. Integrated Gradients are particularly useful for understanding the contributions of specific input features, which can be critical in applications like healthcare, where it is important to know how each clinical feature influences a diagnosis.

Grad-CAM, on the other hand, focuses on visualizing the activations within convolutional layers of a neural network. In a convolutional neural network, the activations of convolutional layers can be thought of as feature maps that capture spatial hierarchies in the input. Grad-CAM computes the gradients of the output with respect to the activations in the last convolutional layer and weights these gradients to produce a class-discriminative localization map. Mathematically, the Grad-CAM heatmap $L_{\text{Grad-CAM}}$ for a given class $c$ is computed as:

$$ L_{\text{Grad-CAM}}^c = \text{ReLU} \left( \sum_k \alpha_k^c A^k \right) $$

where $A^k$ represents the activations of the $k$-th convolutional filter, and $\alpha_k^c = \frac{1}{Z} \sum_{i,j} \frac{\partial f^c}{\partial A_{ij}^k}$ is the weight for the $k$-th filter, determined by the gradients. The resulting heatmap highlights the regions of the input that are most relevant for the prediction of class $c$, offering an intuitive visualization of the model's focus. Grad-CAM is particularly useful for understanding the spatial importance of features in tasks like image classification and object detection.

Another important approach in deep learning interpretability is neural network dissection, a technique that aims to analyze the internal representations learned by the network. By systematically probing the activations of individual neurons, researchers can determine what specific concepts or features each neuron responds to. This method allows for the dissection of the network’s hierarchical feature learning, where earlier layers may detect simple patterns such as edges or textures, while deeper layers capture more abstract and complex features. Neural network dissection provides a mechanism to map neurons to semantic concepts, offering insights into how the network builds its understanding of the input data.

The challenge of interpretability in deep learning remains an active area of research, particularly as models grow in size and complexity. While methods like saliency maps, Integrated Gradients, and Grad-CAM offer valuable tools for understanding the outputs of these models, it is essential to recognize the limitations of these techniques. For example, gradient-based methods are sensitive to the model’s architecture and may not always provide reliable explanations, especially when the gradients are noisy or unstable. Similarly, methods that dissect the network’s neurons can only provide partial insights, as the interactions between neurons are highly complex.

In conclusion, explainability in deep learning is crucial for building trust in AI systems, particularly in applications where accountability and ethical considerations are paramount. By developing and applying techniques such as saliency maps, Integrated Gradients, Grad-CAM, and neural network dissection, we can begin to bridge the gap between performance and interpretability. These methods, implemented in a language like Rust, offer powerful tools for explaining the decisions made by complex deep learning models, thus enabling practitioners to deploy AI systems that are both effective and transparent.

To bring these theoretical concepts into practice, we can implement some of these explainability techniques in Rust. Rust, with its emphasis on safety and performance, is increasingly being utilized for building machine learning applications, allowing developers to leverage its robustness for deep learning tasks. Below is an example of how we might implement a simple saliency map technique for a convolutional neural network (CNN) using the tch-rs crate, which provides Rust bindings for PyTorch.

use tch::{nn::{self, Module}, Device, Tensor};

#[derive(Debug)]

struct SimpleCNN {

conv1: nn::Conv2D,

conv2: nn::Conv2D,

fc: nn::Linear,

}

impl SimpleCNN {

fn new(vs: &nn::Path) -> SimpleCNN {

let conv1 = nn::conv2d(vs, 1, 16, 3, Default::default());

let conv2 = nn::conv2d(vs, 16, 32, 3, Default::default());

let fc = nn::linear(vs, 32 * 5 * 5, 10, Default::default());

SimpleCNN { conv1, conv2, fc }

}

}

impl nn::Module for SimpleCNN {

fn forward(&self, xs: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

println!("Input shape: {:?}", xs.size());

let xs = xs.view([-1, 1, 28, 28]);

println!("Reshaped input: {:?}", xs.size());

let xs = xs.apply(&self.conv1);

println!("After conv1: {:?}", xs.size());

let xs = xs.max_pool2d_default(2);

println!("After max pool1: {:?}", xs.size());

let xs = xs.apply(&self.conv2);

println!("After conv2: {:?}", xs.size());

let xs = xs.max_pool2d_default(2);

println!("After max pool2: {:?}", xs.size());

let xs = xs.view([-1, 32 * 5 * 5]);

println!("Flattened output: {:?}", xs.size());

let xs = xs.apply(&self.fc);

println!("Final output: {:?}", xs.size());

xs

}

}

fn compute_saliency_map(model: &SimpleCNN, input: &Tensor, target_class: i64) -> Tensor {

let output = model.forward(&input);

let target = output.narrow(1, target_class, 1).sum(tch::Kind::Float);

println!("Output before backward: {:?}", output.size());

println!("Target value: {:?}", target);

target.backward();

input.grad().abs().max_dim(1, false).0

}

fn main() {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let model = SimpleCNN::new(&vs.root());

// Create input tensor with requires_grad set to true

let input: Tensor = Tensor::randn(&[1, 28, 28], (tch::Kind::Float, device)).set_requires_grad(true);

let target_class = 5; // Example class index

let saliency_map = compute_saliency_map(&model, &input, target_class);

println!("Saliency Map: {:?}", saliency_map);

}

In this code, we define a simple convolutional neural network (CNN) and implement a function to compute the saliency map. The compute_saliency_map function modifies the input tensor to require gradients, computes the model's output, and then backpropagates to obtain the gradients. The absolute value of the gradients is then processed to create a saliency map that highlights which regions of the input have the most significant impact on the prediction for the specified target class.

In conclusion, the challenge of explainability in deep learning is paramount as we progress toward more complex and capable AI systems. Techniques such as saliency maps, gradient-based explanations, and neural network dissection provide pathways to uncover the decision-making processes of these models. By implementing such techniques in Rust, we can harness the language's safety and efficiency to build interpretable deep learning applications. As we continue to explore these ideas, we must also evaluate the effectiveness and limitations of the chosen methods, ensuring that we maintain a balance between model performance and interpretability in our AI solutions.

23.6. Ethical Considerations in XAI

As artificial intelligence (AI) continues to expand its influence across various domains, the need for explainable AI (XAI) has become not only a technical necessity but also an ethical imperative. The ethical considerations of AI systems extend beyond simple interpretability and delve into fundamental issues such as fairness, transparency, and accountability. These principles are essential for fostering trust and ensuring that AI systems do not perpetuate societal biases or introduce new forms of discrimination. The integration of explainability into AI systems allows practitioners to scrutinize model behavior, ensuring that the decisions made by these systems are fair, transparent, and accountable.

At the heart of ethical AI lies the concept of fairness. Machine learning models, particularly those trained on large datasets, may unintentionally learn biases present in the data. Formally, let $X$ be the feature space and $Y$ be the label space. Suppose that a model $f: X \to Y$ is trained on a dataset $D = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^n$, where $x_i \in X$ and $y_i \in Y$. If certain features within $X$, such as race, gender, or socioeconomic status, are correlated with the labels $Y$, the model may inadvertently associate these sensitive attributes with its predictions. For example, in the case of loan approval models, certain demographic features could lead to unfair discrimination if the model learns to associate them with the likelihood of default.

To mitigate this, fairness can be mathematically defined in several ways, depending on the context. One common notion is demographic parity, where the probability of a positive outcome should be independent of sensitive attributes. This can be expressed as:

$$ P(f(x) = 1 \mid A = a) = P(f(x) = 1 \mid A = b) \quad \text{for all } a, b \in A $$

where $A$ is a sensitive attribute, and $f(x) = 1$ represents a positive prediction. By embedding explainability into AI systems, developers can analyze the decision-making process of the model and identify whether sensitive attributes are influencing predictions in a biased manner. Tools such as feature importance analysis and SHAP values (based on cooperative game theory) can help in attributing the model’s outputs to input features, thus revealing any potential biases and enabling practitioners to adjust the model accordingly.

Transparency is another cornerstone of ethical AI. It refers to the ability of stakeholders—whether they are developers, users, or regulatory bodies—to understand how an AI model functions and why it makes specific decisions. Mathematically, transparency can be viewed as a function of model complexity. Models such as linear regression or decision trees provide a direct mapping between input features and output predictions, allowing for clear interpretations of how the model reaches its decisions. In contrast, more complex models like deep neural networks, which can be represented as compositions of nonlinear functions, obscure this relationship. For instance, in a deep neural network with multiple layers, each layer applies a transformation:

$$ h^{(k)}(x) = \sigma(W^{(k)}h^{(k-1)}(x) + b^{(k)}) $$

where $W^{(k)}$ and $b^{(k)}$ are the weights and biases of the $k$-th layer, and $\sigma$ is the activation function. The intricate composition of these transformations results in a highly nonlinear decision boundary, making it difficult to interpret how the model arrives at its predictions. Explainability techniques such as Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) provide post-hoc transparency by approximating the model's behavior locally or by assigning importance values to input features, respectively. These methods make it possible for stakeholders to understand and verify the decisions of even the most complex models.

Accountability, the third key principle of ethical AI, ensures that practitioners can be held responsible for the decisions made by AI systems. This is particularly important in high-stakes applications, such as healthcare, finance, and criminal justice, where the consequences of AI-driven decisions can be significant. From a regulatory perspective, many governments and institutions are developing guidelines and standards that require AI systems to be explainable and accountable. For instance, the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) enforces the "right to explanation," which mandates that individuals affected by automated decisions have the right to know how those decisions were made.

Conceptually, accountability in AI can be framed within the context of causality. Given a model $f(x)$, accountability requires an understanding of not just the correlations between inputs and outputs but also the causal relationships that drive the model’s predictions. This can be expressed using causal inference techniques such as structural equation models (SEMs) or causal graphs. Let $X$ represent the input features, $Y$ the output, and $Z$ be an intermediate variable. A causal model can be represented as a directed acyclic graph (DAG), where edges indicate causal relationships. In this framework, explainability serves to uncover these relationships, allowing practitioners to verify that the model’s decisions are based on legitimate causal factors rather than spurious correlations.

The ethical dimensions of explainability are not merely theoretical concerns; they have practical implications for how AI systems are designed and deployed. Ensuring fairness requires continuous monitoring and auditing of models to detect and rectify biases, while transparency enables users and stakeholders to engage with AI systems in a meaningful way. Accountability ensures that when an AI system makes a mistake or a harmful decision, there is a clear understanding of how and why it happened, and who is responsible for rectifying the issue.

In conclusion, the ethical implications of explainability in AI are profound. Fairness, transparency, and accountability are not merely desirable features of AI systems; they are essential for ensuring that these systems operate in ways that are just, responsible, and aligned with societal values. As regulatory bodies impose stricter guidelines on the deployment of AI, the role of explainability will continue to grow in importance. Practitioners must, therefore, integrate robust explainability practices into the design and deployment of their AI models, ensuring that these systems are not only performant but also ethical.

In practical terms, implementing fairness-aware explainability techniques in Rust can be accomplished by leveraging existing libraries and frameworks while adhering to ethical guidelines. Rust, with its strong safety guarantees and performance characteristics, is an excellent choice for developing robust AI solutions. For instance, one can use the linfa crate, which provides a range of machine learning algorithms, to train models while incorporating fairness considerations. Below is an illustrative example of how one might implement a simple classification model using the linfa crate and evaluate it for bias.

// Append Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

linfa = "0.7.0"

linfa-trees = "0.7.0"

ndarray = "0.15.1"

use linfa::prelude::*;

use linfa_trees::DecisionTree;

use linfa::Dataset;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

fn main() {

// Sample dataset with features and labels

let features = Array2::from_shape_vec((6, 2), vec![

1.0, 0.0, // Class 0

0.0, 1.0, // Class 1

1.0, 0.5, // Class 0

0.5, 0.0, // Class 1

0.0, 0.5, // Class 1

1.0, 1.0, // Class 0

]).unwrap();

let labels = Array1::from_vec(vec![0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0]);

let dataset = Dataset::new(features.clone(), labels.clone());

// Train a Decision Tree model

let model = DecisionTree::params().fit(&dataset).unwrap();

// Evaluate the model

let predictions = model.predict(&dataset);

let accuracy = (predictions.iter().zip(labels.iter()).filter(|(a, b)| a == b).count() as f64) / (labels.len() as f64);

println!("Model Accuracy: {}", accuracy);

}

After training the model, practitioners can assess its fairness by analyzing the predictions across different demographic groups. For instance, one might calculate the true positive rate or false positive rate for each group to identify disparities. If significant biases are detected, practitioners can utilize techniques such as re-weighting the training data or adjusting model thresholds to ensure fairer outcomes.

Furthermore, integrating XAI techniques into the workflow can help elucidate the model's decision-making process, thus reinforcing accountability. Libraries such as shap and lime (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) can be utilized to generate local explanations for individual predictions. While these libraries may not have direct Rust implementations, one can create bindings or leverage FFI (Foreign Function Interface) to interact with them, ensuring that the model's predictions can be explained in a human-understandable manner.

In summary, the ethical considerations surrounding explainable AI are multifaceted and require a concerted effort to ensure fairness, transparency, and accountability in AI systems. By embedding explainability into the fabric of machine learning applications in Rust, practitioners can create models that not only perform well but also adhere to ethical standards. This approach not only mitigates bias and discrimination but also aligns with the growing demand for responsible AI practices in an increasingly regulated environment.

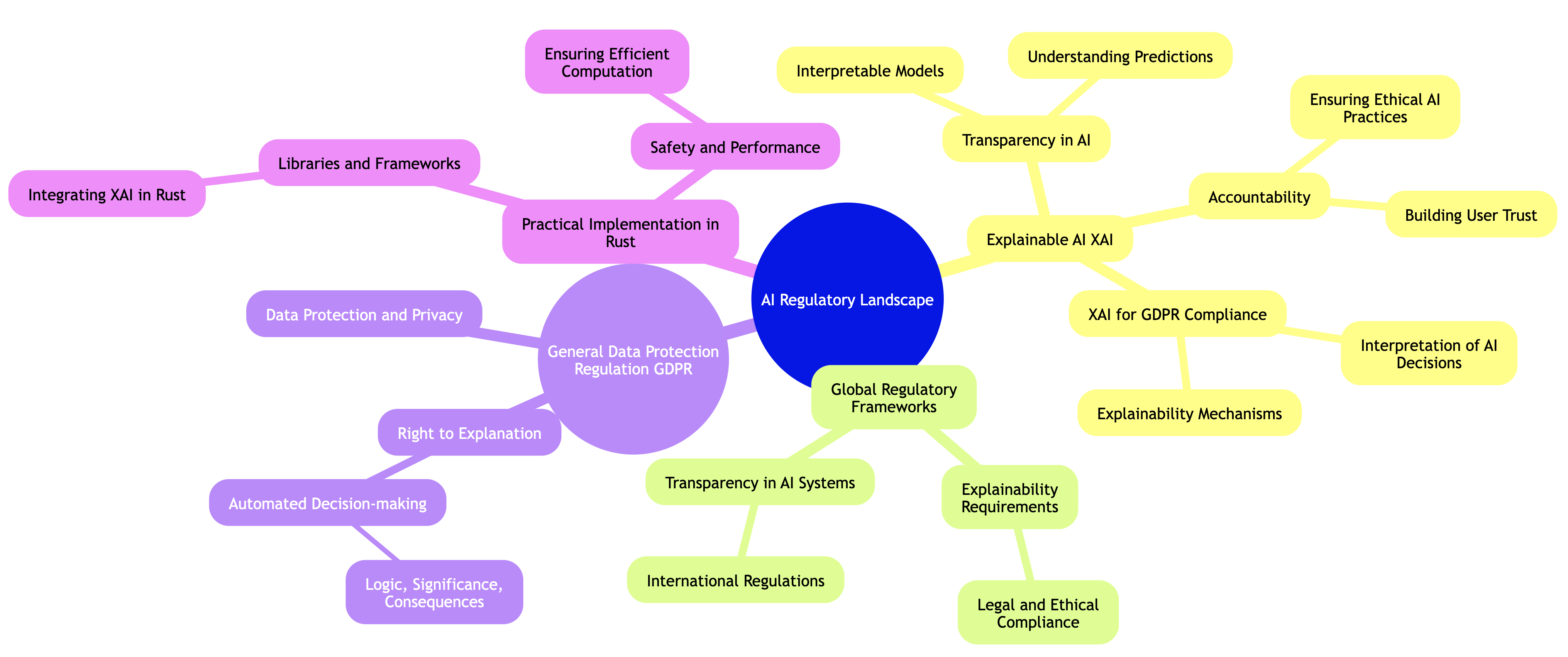

23.7. Regulatory and Compliance Aspects of XAI

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) has spurred the creation of regulatory frameworks designed to ensure ethical practices, transparency, and accountability in AI systems. These regulations are necessary to address the concerns of privacy, fairness, and security that arise when AI systems are used in decision-making processes. One of the most prominent regulations in this domain is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a legal framework established by the European Union (EU) to protect individual data privacy and promote responsible data usage.

Figure 4: AI regulatory landscape in Mind Map format.

At the core of GDPR is the principle of data protection, which includes the right to explanation. This right stipulates that individuals must be provided with information regarding the logic, significance, and potential outcomes of automated decisions that affect them. This aspect of GDPR is particularly important in the context of AI systems, which often involve complex algorithms and automated decision-making processes that are difficult to interpret. The right to explanation ensures that these systems remain accountable by providing clarity and transparency into how AI models reach their decisions. This aligns closely with the principles of Explainable AI (XAI), a growing field that seeks to make AI models more interpretable, understandable, and transparent.

XAI plays a pivotal role in ensuring compliance with GDPR and other similar regulations. Organizations that deploy AI systems must be able to provide clear explanations for the outcomes generated by their models. This involves making AI systems interpretable not just to data scientists but also to end-users, regulators, and other stakeholders. By adopting XAI techniques, organizations can better meet regulatory requirements, build trust with users, and mitigate potential legal risks associated with opaque AI decision-making.

Globally, regulatory frameworks are increasingly emphasizing the need for explainability in AI systems. Many countries outside the EU are also introducing laws that require transparency in automated decision-making. As a result, organizations that leverage AI technologies must stay ahead of these evolving regulations by integrating XAI into their systems. In practical terms, this involves selecting or designing AI models that are explainable, implementing mechanisms to interpret decisions, and ensuring that explanations are accessible and understandable to non-experts.

In the context of Rust, implementing regulatory-compliant XAI involves integrating libraries and frameworks that facilitate interpretability and transparency. Rust's focus on performance and safety makes it a strong candidate for developing AI systems that meet regulatory standards while maintaining efficient computation. This practical approach to ensuring regulatory compliance with XAI emphasizes the importance of ethical and accountable AI practices in modern software development.

In terms of practical implementation, organizations can leverage Rust to develop AI systems that incorporate explainability features. Rust's performance and safety make it an excellent choice for building robust AI applications. To illustrate how one might implement an XAI feature in Rust, consider a simple logistic regression model that predicts binary outcomes. The goal is to create a function that not only makes predictions but also provides explanations for those predictions based on feature importance.

use linfa;

use linfa::prelude::*;

use linfa_logistic::LogisticRegression;

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

fn main() {

// Sample data: 4 observations, 2 features

let features = Array2::from_shape_vec(

(4, 2),

vec![1.0, 2.0, 1.5, 1.2, 2.5, 2.1, 3.0, 1.0]

).unwrap();

let targets = Array1::from_vec(vec![0, 0, 1, 1]);

let dataset = Dataset::new(features, targets);

// Train the logistic regression model

let model = LogisticRegression::default().fit(&dataset).unwrap();

// Make a prediction

let new_data = Array2::from_shape_vec((1, 2), vec![2.0, 1.5]).unwrap();

let prediction = model.predict(&new_data);

// Print the prediction

println!("Prediction: {:?}", prediction);

// Explain the prediction using feature importance

let coefficients = model.params();

println!("Feature importance: {:?}", coefficients);

}

In the example above, we first train a logistic regression model using the linfa crate, which is a Rust machine learning library. After generating predictions, we can also extract the coefficients of the model, which serve as a measure of feature importance. These coefficients can be interpreted as the contribution of each feature to the final prediction, thus providing an explanation that can satisfy the requirements of regulatory frameworks like the GDPR.

In addition to implementing explainability features, organizations must also focus on creating documentation that aligns with legal and ethical standards. This documentation should detail the decision-making processes of AI systems, the methodologies used to derive explanations, and how the organization ensures compliance with relevant regulations. By maintaining comprehensive records of how AI systems operate and the steps taken to ensure transparency, organizations can not only safeguard against regulatory scrutiny but also promote a culture of accountability within their AI practices.

In conclusion, as AI technologies continue to proliferate, the need for compliance with regulatory frameworks becomes ever more pressing. Explainable AI offers a pathway for organizations to align their AI systems with the expectations set forth by regulators. By understanding the fundamental principles of regulations like the GDPR, conceptualizing the requirements for explainability, and practically implementing these features in robust programming environments like Rust, organizations can navigate the complex landscape of AI compliance effectively. This proactive approach not only mitigates legal risks but also fosters public trust in the deployment of AI systems.

23.8. Future Directions in Explainable AI

As we delve into the future directions of Explainable AI (XAI), it is essential to recognize the fundamental ideas that shape this evolving landscape. Emerging trends in XAI are predominantly characterized by an increasing demand for transparency and interpretability in AI systems. As organizations and individuals increasingly rely on AI for critical decision-making, the necessity for understanding the rationale behind these decisions becomes paramount. One of the primary challenges in making AI systems more interpretable lies in the inherent complexity of many machine learning models, particularly deep learning architectures. These models often operate as "black boxes," where the intricate network of parameters and weights obscures the decision-making process.

Ongoing research in this field aims to bridge the gap between model performance and interpretability. The exploration of novel interpretability techniques, such as feature importance analysis, local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME), and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), showcases the strides being made to make AI systems more understandable. Furthermore, the conceptual ideas driving the future of XAI include the integration of advanced interpretability techniques into the AI development lifecycle. This integration can facilitate the creation of inherently interpretable models that not only achieve high predictive accuracy but also offer insights into their reasoning processes.

In practical terms, implementing cutting-edge XAI techniques in Rust presents a unique opportunity for developers and data scientists to contribute to the advancement of model transparency. Rust, known for its performance and safety features, is an excellent language for building robust AI systems. For example, let us consider implementing the LIME algorithm in Rust, which allows us to generate locally interpretable explanations for black-box models. The following code snippet illustrates a simplified version of how LIME can be implemented in Rust:

use ndarray::Array2;

use rand::random;

fn lime_predict(model: &dyn Fn(Array2<f32>) -> Vec<f32>, instance: Array2<f32>, num_samples: usize) -> Vec<f32> {

let mut perturbed_samples = Array2::<f32>::zeros((num_samples, instance.shape()[1]));

for i in 0..num_samples {

for j in 0..instance.shape()[1] {

perturbed_samples[[i, j]] = instance[[0, j]] + random::<f32>() * 0.1; // Perturbing the instance

}

}

// Getting predictions from the model

let predictions = model(perturbed_samples);

// Here we would typically compute weights and fit a local interpretable model

predictions

}

fn main() {

let model = |input: Array2<f32>| -> Vec<f32> {

input.axis_iter(ndarray::Axis(0)) // Iterate over the rows

.map(|row| row.sum())

.collect() // Simple mock model

};

let instance = Array2::from_shape_vec((1, 3), vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0]).unwrap();

let predictions = lime_predict(&model, instance, 100);

println!("Predictions: {:?}", predictions);

}

In this example, we define a simple mock model that sums the input features. The lime_predict function perturbs the input instance to create a set of new samples and retrieves predictions for those samples. In real-world applications, one would compute the appropriate weights and fit a simple interpretable model to these predictions to generate explanations.

As we look ahead, the future challenges of XAI will likely revolve around ensuring that interpretability techniques not only provide insights but also maintain the performance of the underlying models. The balance between model accuracy and interpretability is a delicate one, and ongoing research will be essential in addressing this challenge. Moreover, as the field of AI continues to evolve, the integration of XAI principles into regulatory frameworks and ethical guidelines will become increasingly important. This will help ensure that AI systems are not only effective but also accountable and fair.

In conclusion, the future of Explainable AI is bright, with numerous avenues for research and implementation. The combination of fundamental, conceptual, and practical ideas will lead to the development of more advanced interpretability techniques and their seamless integration into the AI development lifecycle. As we continue to explore these themes in Rust, we can contribute to a future where AI systems are not only powerful but also transparent and comprehensible, fostering trust among users and stakeholders alike.

23.9. Conclusion

This chapter equips you with the knowledge and tools necessary to make your machine learning models explainable and interpretable. By mastering these techniques in Rust, you will ensure that your models are transparent, ethical, and aligned with the growing demand for responsible AI.

23.9.1. Further Learning with GenAI

By exploring these prompts, you will deepen your knowledge of the theoretical foundations, practical applications, and advanced techniques in XAI, equipping you to build, deploy, and maintain interpretable machine learning models.

Explain the importance of Explainable AI (XAI) in modern machine learning systems. How does XAI contribute to building trust, ensuring fairness, and meeting regulatory requirements? Implement a basic XAI framework in Rust.

Discuss the difference between global and local explanations in XAI. How do these approaches help in understanding model behavior at different levels, and what are their respective strengths and weaknesses? Implement global and local explanation techniques in Rust.

Analyze the role of model-agnostic techniques like LIME and SHAP in XAI. How do these techniques provide insights into complex models, and what are the challenges of implementing them? Implement LIME and SHAP in Rust for a complex machine learning model.

Explore the trade-offs between model complexity and interpretability. When should simpler, interpretable models be preferred over more complex, black-box models? Implement and compare interpretable models and black-box models in Rust.

Discuss the importance of visualization in making models interpretable. How do visualization tools like feature importance plots and decision paths help in understanding model decisions? Implement visualization techniques in Rust for model interpretability.

Analyze the challenges of explaining deep learning models. How do techniques like saliency maps and gradient-based explanations help in making neural networks more interpretable? Implement explainability techniques for deep learning models in Rust.

Explore the ethical implications of XAI. How does making models explainable contribute to fairness, transparency, and accountability in AI systems? Implement fairness-aware explainability techniques in Rust and evaluate their impact.

Discuss the regulatory requirements for explainability in AI. How do frameworks like GDPR mandate explainability, and how can XAI help organizations comply with these regulations? Implement compliance-focused XAI features in Rust.

Analyze the impact of XAI on user trust and adoption of AI systems. How does providing clear explanations improve user confidence in AI models, and what are the best practices for communicating model decisions? Implement user-friendly explanation interfaces in Rust.

Explore the future directions of research in Explainable AI. What are the emerging trends and challenges in XAI, and how can new techniques contribute to more transparent AI systems? Implement cutting-edge XAI techniques in Rust.