Chapter 24

Federated Learning and Privacy-Preserving ML

"The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existence." — Albert Einstein

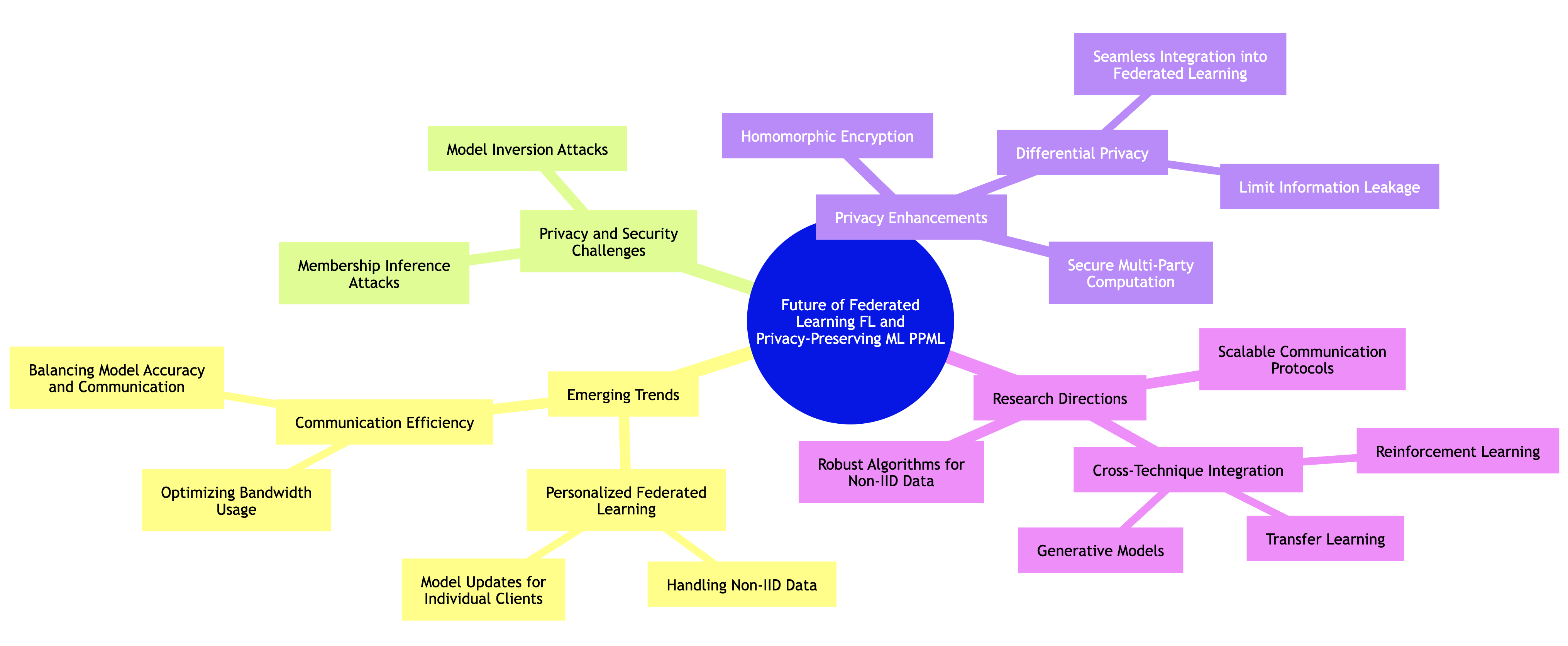

Chapter 24 of MLVR provides a comprehensive exploration of Federated Learning and Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning (PPML), crucial approaches for training machine learning models on distributed data while maintaining data privacy and security. The chapter begins by introducing the fundamental concepts of Federated Learning, highlighting the benefits of decentralized model training in scenarios where data cannot be centralized. It then delves into privacy-preserving techniques such as differential privacy and homomorphic encryption, which are essential for ensuring that individual data remains secure during the training process. The chapter also addresses the communication efficiency challenges in Federated Learning, discussing strategies to minimize communication overhead while maintaining model accuracy. Security risks, including potential attacks on Federated Learning systems, are thoroughly explored, along with practical measures to mitigate these risks. The chapter further examines the application of Federated Learning in edge computing and IoT, where data is generated at the edge of the network, and the unique challenges of deploying models in resource-constrained environments. Real-world applications of Federated Learning in domains such as healthcare, finance, and smart cities are presented, along with discussions on regulatory and ethical considerations that must be addressed when implementing these technologies. Finally, the chapter looks ahead to the future of Federated Learning and PPML, discussing emerging trends, ongoing research, and the challenges that lie ahead. By the end of this chapter, readers will have a deep understanding of how to implement Federated Learning and Privacy-Preserving ML techniques using Rust, ensuring that their machine learning models are not only powerful but also secure, efficient, and compliant with ethical and regulatory standards.

24.1. Introduction to Federated Learning

Federated Learning (FL) represents a transformative approach in machine learning, designed to address the pressing challenges of data privacy and security in a world that increasingly relies on vast amounts of sensitive information. At its core, federated learning enables multiple clients, which could range from mobile devices to Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, to collaboratively train a shared machine learning model without requiring the raw data from these clients to be transmitted to a central server. This approach not only preserves the privacy of individual data points but also reduces the communication overhead typically associated with centralized learning, where large datasets are transferred to a central server. Federated learning fundamentally redefines how data is utilized, with privacy-preserving mechanisms that are crucial in the context of stringent data regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

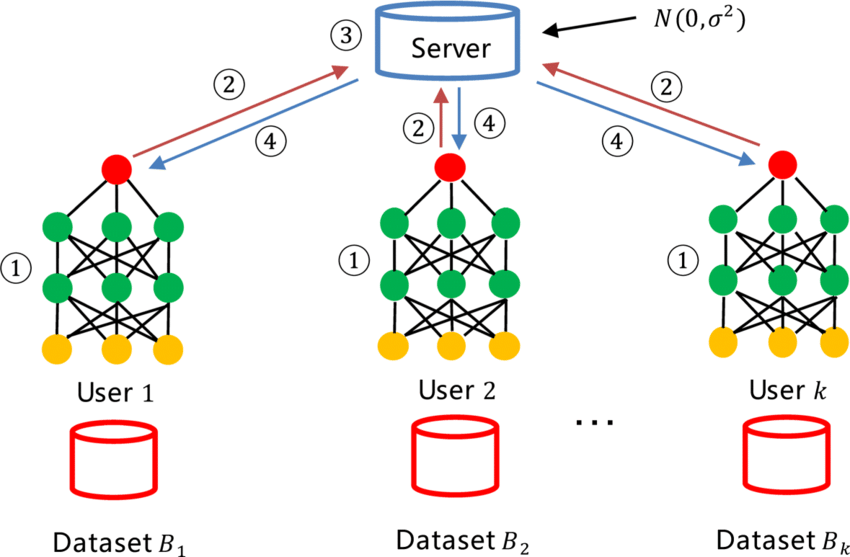

Figure 1: Analogy for Federated Learning model.

Federated learning can be likened to a team of doctors, each working at different hospitals, who collaborate to develop a shared treatment model for a disease. However, these doctors do not share their patient data directly; instead, they exchange insights derived from their local work. In this analogy, User 1 is a doctor at Hospital $B_1$ who works with Dataset $B_1$, User 2 is another doctor at Hospital $B_2$ with Dataset $B_2$, and so on, up to User $k$, who has Dataset $B_k$ at Hospital $B_k$. Each of these doctors wants to contribute to building a global AI model for disease prediction or treatment, but without exposing their patients' sensitive data to others.

The process begins with each doctor training their own AI model locally on their dataset. For example, User 1 trains Model 1 on Dataset $B_1$, User 2 trains Model 2 on Dataset $B_2$, and User $k$ trains Model k on Dataset $B_k$. This local training ensures that no raw patient data leaves any hospital, preserving patient privacy. Once the local models are trained, instead of sharing the raw data, the doctors upload only the model parameters (the weights and patterns learned during the training) to a central aggregation server. This server acts like a team leader who combines the insights provided by each doctor without accessing their underlying data.

The central aggregation server then gathers the model parameters from all the users—User 1, User 2, ..., User k—and aggregates them to create a global model. This global model represents the combined knowledge of all the doctors, providing a more robust and generalizable treatment model. However, to ensure that the model does not inadvertently reveal sensitive information from individual hospitals' data, the central server applies a technique called Concentrated Differential Privacy (CDP). CDP works by adding noise to the aggregated model parameters, which ensures that even if someone tried to reverse-engineer the information, they would not be able to extract any private data related to the patients. This method strikes a balance between model accuracy and data privacy.

Once the central server has aggregated the model parameters and added the necessary noise for privacy, it sends the updated global model back to each doctor. User 1, User 2, and User k then download these global model parameters and continue refining their local models, benefiting from the collective insights of the entire group. Each user, therefore, improves their model without ever exposing their raw data to others, ensuring privacy and security while enhancing the overall accuracy and performance of the AI system.

In essence, federated learning allows different entities, such as hospitals, to work together to build a shared model without compromising the privacy of their data. The central aggregation server coordinates this effort, ensuring that privacy is maintained using techniques like differential privacy, making federated learning particularly useful in fields like healthcare, where data sensitivity and privacy are paramount.

To understand federated learning in its entirety, it is important to contrast it with the traditional centralized learning paradigm. In centralized learning, the entire training dataset is collected at a central location, often resulting in concerns about data privacy, security, and vulnerability to single points of failure. Formally, consider a dataset $D = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^n$, where $x_i \in \mathbb{R}^d$ are input features and $y_i \in \mathbb{R}$ are labels. In centralized learning, this dataset is aggregated at the server, and the model $f_{\theta}$, parameterized by $\theta \in \mathbb{R}^p$, is trained on the entire dataset by minimizing a loss function $\mathcal{L}(\theta, D)$. The objective is typically to find optimal parameters $\theta^*$ that minimize the empirical risk:

$$ \theta^* = \arg \min_{\theta} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \mathcal{L}(f_{\theta}(x_i), y_i) $$

However, this centralized framework raises privacy concerns, as all data is pooled at a single location, making it vulnerable to data breaches and regulatory non-compliance.

In contrast, federated learning decentralizes the training process, allowing model training to occur locally on each client’s device. Let $\mathcal{C} = \{C_1, C_2, \dots, C_k\}$ represent a set of $k$ clients, where each client $C_j$ possesses its own local dataset $D_j = \{(x_{ij}, y_{ij})\}_{i=1}^{n_j}$. Instead of transmitting $D_j$ to the central server, the model $f_{\theta}(x)$ is trained locally on each client’s data. Mathematically, each client solves a local optimization problem:

$$ \theta_j^* = \arg \min_{\theta} \frac{1}{n_j} \sum_{i=1}^{n_j} \mathcal{L}(f_{\theta}(x_{ij}), y_{ij}) $$

The updates $\theta_j^*$ from each client are then sent to the central server, where they are aggregated to update the global model. One common aggregation technique is Federated Averaging (FedAvg), which updates the global model $\theta$ by averaging the model updates from each client. Let $n = \sum_{j=1}^k n_j$ be the total number of data points across all clients. The global model update in FedAvg is expressed as:

$$ \theta = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=1}^k n_j \theta_j^* $$

This aggregated model is then broadcast back to the clients, where the local training and aggregation process is repeated in subsequent communication rounds. Through this iterative process, federated learning enables the construction of a global model without ever requiring the raw data to leave the clients’ devices, thereby preserving privacy.

A critical challenge in federated learning arises from the fact that the local datasets $D_j$ on different clients are often non-IID (non-independent and identically distributed). In other words, the data distributions across clients may vary significantly due to differences in usage patterns, geographic locations, or device characteristics. Formally, let $P_j(x, y)$ represent the data distribution for client $C_j$. In non-IID settings, $P_j(x, y) \neq P_{j'}(x, y)$ for some clients $j$ and $j'$. This distributional heterogeneity can complicate the model training process, as the aggregated updates from clients may not fully capture the global data distribution. Techniques such as FedProx have been proposed to address these challenges by modifying the local optimization objective to better handle non-IID data and ensure convergence to a robust global model.

Another crucial advantage of federated learning is its ability to leverage the computational resources of the clients themselves. By offloading the model training to the edge devices, federated learning reduces the computational burden on the central server and enables scalable machine learning on a wide range of devices. This is particularly relevant in the context of resource-constrained environments such as IoT networks, where devices may have limited processing power and bandwidth. The distributed nature of federated learning makes it well-suited for scenarios where data is generated at the edge and transferring large volumes of data to a central server would be impractical or inefficient.

From a privacy-preserving perspective, federated learning offers significant advantages by minimizing the exposure of raw data. However, the transmission of model updates between clients and the central server still poses potential privacy risks, as these updates can sometimes leak information about the underlying data. To mitigate this, techniques such as differential privacy and secure multiparty computation are often employed alongside federated learning. Differential privacy ensures that the updates sent by each client do not reveal sensitive information about individual data points by introducing controlled noise into the updates. Formally, a randomized mechanism $M$ satisfies $\epsilon$-differential privacy if for any two neighboring datasets $D$ and $D'$ that differ by one data point, and for any output set $S$:

$$ P(M(D) \in S) \leq e^{\epsilon} P(M(D') \in S) $$

This ensures that the model updates from any client are statistically indistinguishable from updates that would have been generated by a slightly different dataset, thereby protecting the privacy of individual data points.

In conclusion, federated learning represents a paradigm shift in how we think about privacy, security, and data usage in machine learning. By decentralizing the training process and enabling clients to retain control over their data, federated learning addresses many of the privacy concerns inherent in traditional centralized approaches. Moreover, by leveraging the computational power of edge devices, federated learning offers a scalable solution for training robust machine learning models across diverse and distributed datasets. As privacy regulations continue to evolve, federated learning will play an increasingly important role in ensuring that machine learning systems remain both effective and compliant with ethical standards.

To illustrate the principles of federated learning in practice, we can develop a basic federated learning framework in Rust. The following code example simulates a federated environment with multiple clients and demonstrates the process of aggregating model updates on a server. We will utilize the ndarray crate for matrix operations, which are integral to machine learning operations.

First, we need to define our model and the basic structures required for clients and the server.

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2};

use ndarray_rand::RandomExt;

use rand::distributions::Uniform;

struct Model {

weights: Array1<f32>,

}

impl Model {

fn new(size: usize) -> Self {

Self {

weights: Array1::zeros(size),

}

}

fn update(&mut self, delta: &Array1<f32>) {

self.weights += delta;

}

}

struct Client {

model: Model,

data: Array2<f32>, // Each row is a data point

}

impl Client {

fn new(data: Array2<f32>, model_size: usize) -> Self {

Self {

model: Model::new(model_size),

data,

}

}

fn train(&mut self) -> Array1<f32> {

// Simulated training logic (e.g., gradient descent)

let updates = self.data.mean_axis(ndarray::Axis(0)).unwrap();

updates

}

}

struct Server {

global_model: Model,

}

impl Server {

fn new(model_size: usize) -> Self {

Self {

global_model: Model::new(model_size),

}

}

fn aggregate(&mut self, updates: &Vec<Array1<f32>>) {

let sum: Array1<f32> = updates.into_iter().fold(Array1::zeros(self.global_model.weights.len()), |acc, x| acc + x);

let avg = sum / updates.into_iter().len() as f32;

self.global_model.update(&avg);

}

}

In this example, we create a Model struct that holds the weights of our machine learning model. The Client struct represents individual clients, each with its own dataset and a method to simulate local training. The Server struct is responsible for aggregating updates from all clients and updating the global model accordingly.

Next, let's simulate a federated learning scenario with multiple clients.

fn main() {

let num_clients = 5;

let model_size = 3;

let mut clients: Vec<Client> = Vec::new();

let mut server = Server::new(model_size);

// Simulate data for each client

for _ in 0..num_clients {

let client_data = Array2::random((10, model_size), Uniform::new(0., 1.));

clients.push(Client::new(client_data, model_size));

}

let mut updates: Vec<Array1<f32>> = Vec::new();

// Each client trains locally and sends updates to the server

for client in clients.iter_mut() {

let update = client.train();

updates.push(update);

}

// Server aggregates the updates

server.aggregate(&updates);

println!("Updated global model weights: {:?}", server.global_model.weights);

}

In this main function, we instantiate a number of clients, each with random data, and simulate the training process. After each client has trained its model, it sends its updates to the server, which aggregates these updates to improve the global model. The code demonstrates the fundamental workflow of federated learning, showcasing the local training and aggregation process in a straightforward manner.

By implementing federated learning in Rust, we not only leverage the performance and safety features of the language but also create a framework that can be adapted for more complex scenarios, including privacy-preserving techniques such as differential privacy or secure multi-party computation. This foundational understanding of federated learning sets the stage for more advanced discussions on privacy-preserving machine learning and its applications in real-world scenarios.

24.2. Privacy-Preserving Techniques in Federated Learning

Imagine a group of hospitals that each have valuable medical imaging data, such as X-rays or MRIs, but none of these hospitals want to share this sensitive data directly due to privacy concerns. They recognize that if they could combine their knowledge, they could build a better AI model to diagnose diseases more accurately, benefiting all of their patients. However, they need a way to do this without compromising patient privacy. This is where secure, privacy-preserving federated learning comes into play, providing a method for these hospitals to work together while keeping the data secure and protected.

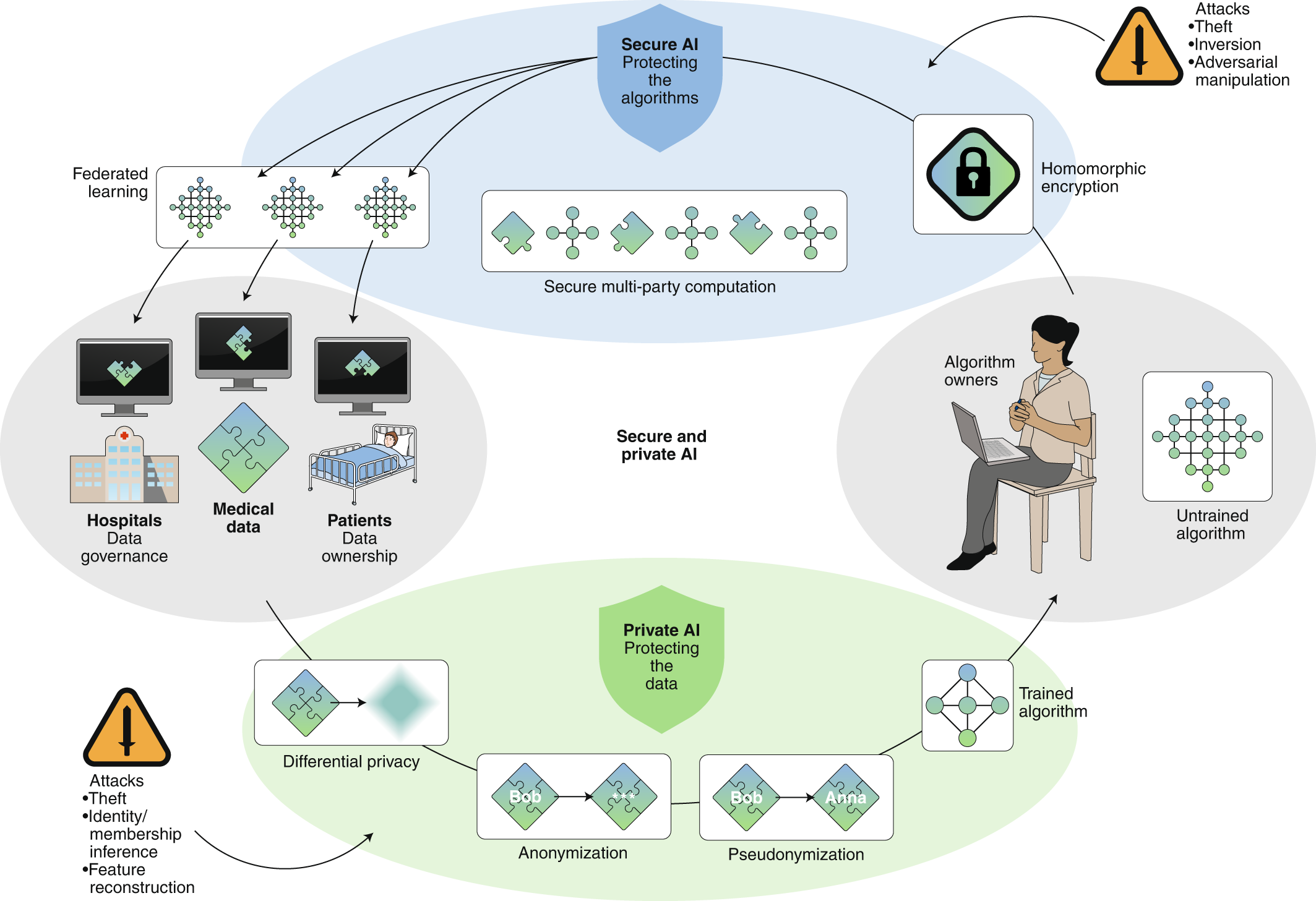

Figure 2: Secure, privacy-preserving and federated ML in medical imaging.

Each hospital (like Hospital A, Hospital B, etc.) holds its own set of medical images and patient data. Hospital A trains a local AI model on its images without sending any raw data to other hospitals. Hospital B does the same, training a local AI model on its own data. This allows each hospital to maintain ownership and control over their data—a principle referred to as data governance. Data governance ensures that each hospital retains full control over who accesses their data and how it’s used, preserving patient confidentiality and regulatory compliance. In this scenario, privacy is protected through techniques like anonymization and pseudonymization, where sensitive identifiers (like patient names or personal details) are removed or replaced, so the data cannot be linked back to individual patients.

Once each hospital has trained its local model, they do not share the data itself but rather the model parameters, which are the results of their local training. These parameters are sent to a central server that aggregates the results from all participating hospitals. However, even the model parameters can carry some risk of revealing sensitive patterns from the data. To address this, the hospitals use Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC), which ensures that the process of aggregating these parameters is done in a completely secure and encrypted manner. SMPC works like a virtual lockbox—each hospital contributes its piece of the puzzle without revealing any individual parts to the other hospitals or the central server. The combined AI model is then built from these contributions, but no hospital ever sees the data from another hospital, nor can any unauthorized party access it.

Additionally, this process employs secure AI techniques to further protect both the algorithms and the data. Secure AI ensures that the machine learning algorithms themselves are safeguarded from attacks that might try to manipulate or gain insights from the training process. This protects both the integrity of the algorithm and the privacy of the medical data used to train it. The central server may also use homomorphic encryption, which allows it to perform computations on encrypted data without needing to decrypt it, ensuring that the data remains protected even during the aggregation process.

Moreover, the hospitals add an additional layer of security using differential privacy. In this approach, the central server injects a small amount of statistical noise into the aggregated model parameters, making it mathematically impossible to trace back any individual hospital’s data from the final global model. This ensures that even though the hospitals are collaborating, the privacy of their patients is never compromised.

In this analogy, the hospitals represent different entities with valuable yet sensitive data. Through the combination of federated learning, secure AI, secure multi-party computation, and strong data governance measures like anonymization and pseudonymization, they are able to collaborate to build a more powerful medical imaging model while ensuring that patient privacy and data ownership remain intact.

In the context of federated learning, privacy-preserving techniques are essential for ensuring that sensitive data remains confidential while still enabling the collaborative training of machine learning models. The primary techniques employed to achieve this goal include differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, and secure multi-party computation (MPC). Each of these techniques provides a mathematical and algorithmic framework for maintaining the privacy of individual data points, even as aggregate model updates are shared and used to improve a global model. The theoretical foundation of these techniques involves striking a balance between privacy and utility, as increasing privacy protection often comes at the cost of model performance.

Differential privacy is a well-established mathematical framework designed to provide robust privacy guarantees when processing data. It operates on the principle that the output of a function should not significantly change whether or not any individual’s data is included in the dataset. Formally, a randomized algorithm $M$ is said to satisfy $\epsilon$-differential privacy if, for any two neighboring datasets $D$ and $D'$ that differ by exactly one data point, and for any subset of possible outputs $S$, the following condition holds:

$$ P(M(D) \in S) \leq e^{\epsilon} P(M(D') \in S) $$

Here, $\epsilon$ represents the privacy budget, which controls the level of privacy; smaller values of $\epsilon$ provide stronger privacy guarantees. In the federated learning context, differential privacy is typically implemented by adding random noise to the model updates before they are sent from the client to the server. For instance, let $\theta_j$ represent the local model parameters on client $j$. Instead of sending $\theta_j$ directly to the server, the client sends a perturbed version $\hat{\theta}_j = \theta_j + \eta_j$, where $\eta_j$ is noise sampled from a distribution such as the Laplace or Gaussian distribution, depending on the specific privacy requirements. The server then aggregates these noisy updates to update the global model:

$$ \theta_{\text{global}} = \frac{1}{k} \sum_{j=1}^k \hat{\theta}_j $$

The challenge with differential privacy lies in balancing the noise level and the model’s utility. Excessive noise can degrade the performance of the global model, while insufficient noise can expose sensitive information. Advanced techniques like the moments accountant are often employed to track the cumulative privacy loss across multiple iterations of the federated learning process, ensuring that the overall privacy guarantees remain within acceptable limits.

Homomorphic encryption offers an entirely different approach to privacy preservation. Unlike differential privacy, which relies on perturbing the data, homomorphic encryption allows computations to be performed directly on encrypted data. Let $E(x)$ represent the encryption of a data point $x$. Homomorphic encryption ensures that for any functions $f$ and $g$, it holds that:

$$ E(f(x) + g(y)) = E(f(x)) + E(g(y)) $$

This property allows the central server in a federated learning setup to aggregate encrypted model updates without decrypting them, thereby preserving the confidentiality of the individual updates. For example, if $\theta_j$ is the local model update from client $j$, instead of sending $\theta_j$ in plaintext, the client encrypts $\theta_j$ using a public key $pk$ and sends $E_{pk}(\theta_j)$ to the server. The server can then compute the aggregate update $\theta_{\text{global}}$ using the homomorphic property, without needing access to the plaintext updates. Once the aggregation is complete, the server can send the encrypted result back to the clients, who can decrypt it with their private keys. One of the key advantages of homomorphic encryption is that it ensures complete data confidentiality, as the raw model updates are never exposed during the aggregation process. However, homomorphic encryption is computationally expensive, especially for large-scale models, as operations on encrypted data are significantly slower than on plaintext data.

Secure multi-party computation (MPC) is another technique that enables multiple parties to jointly compute a function over their inputs while keeping those inputs private. In the federated learning context, MPC can be used to securely aggregate model updates from multiple clients without revealing individual updates to any party, including the central server. Let $f(\theta_1, \theta_2, \dots, \theta_k)$ be the aggregation function that combines the local model updates from $k$ clients. In an MPC framework, each client holds a share of the input, and the computation of $f$ is distributed across all clients. The key idea is that the clients collaboratively compute the function in such a way that no individual client learns anything about the other clients’ inputs. Formally, given inputs $\theta_1, \theta_2, \dots, \theta_k$, MPC protocols ensure that the output $f(\theta_1, \dots, \theta_k)$ is revealed, but the individual values of $\theta_1, \dots, \theta_k$ remain private.

In practice, this can be achieved through secret sharing techniques. For instance, each client splits its local model update $\theta_j$ into multiple shares and distributes these shares among the other clients. The clients then perform computations on the shares, and the final result is reconstructed without any client learning the full value of any other client’s update. One commonly used MPC protocol is Shamir’s Secret Sharing, where the model update $\theta_j$ is split into ttt shares using a polynomial of degree $t-1$, ensuring that no subset of fewer than ttt shares can reconstruct the secret. The resulting aggregated update can then be reconstructed by the central server or by the clients themselves.

The main challenge with MPC lies in the computational and communication overhead. As the number of clients increases, the number of shares and the complexity of the computation grow, making it difficult to scale MPC protocols for large federated learning systems. Nevertheless, MPC provides strong privacy guarantees by ensuring that the individual model updates remain hidden during the aggregation process.

In conclusion, privacy-preserving techniques such as differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, and secure multi-party computation are critical components of federated learning systems. Each of these techniques offers unique advantages and trade-offs in terms of privacy, computational efficiency, and model utility. Differential privacy provides strong theoretical guarantees by perturbing the model updates, homomorphic encryption allows computations on encrypted data, and MPC enables secure joint computations without revealing individual inputs. Together, these techniques form the backbone of privacy-preserving federated learning, ensuring that sensitive data remains secure while enabling the collaborative training of machine learning models across distributed networks.

Transitioning from the conceptual understanding of these techniques to their practical implementation, we can explore how to embed differential privacy and homomorphic encryption into a Rust-based federated learning framework. For differential privacy, we can utilize Rust's numerical libraries to add noise to model updates. Below is a simplified example demonstrating how to implement differential privacy in a federated learning context using Rust.

use rand;

use rand::Rng;

struct ModelUpdate {

weights: Vec<f32>,

}

fn apply_differential_privacy(update: &ModelUpdate, epsilon: f32) -> ModelUpdate {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let noise: Vec<f32> = update.weights.iter().map(|w| {

let noise: f32 = rng.gen_range(-1.0..1.0) * (1.0 / epsilon);

w + noise

}).collect();

ModelUpdate { weights: noise }

}

fn main() {

let update = ModelUpdate { weights: vec![0.5, 0.2, 0.1] };

let epsilon = 0.1; // Privacy budget

let private_update = apply_differential_privacy(&update, epsilon);

println!("{:?}", private_update.weights);

}

In the above code, we define a ModelUpdate struct that holds the model weights. The function apply_differential_privacy takes in a model update and an epsilon value, which represents the privacy budget. It generates random noise and applies it to each weight, thereby creating a private update.

For homomorphic encryption, Rust libraries like tfhe provide a way to perform operations on encrypted data. Below is a practical example of how one might set up a homomorphic encryption scheme using the tfhe crate in Rust.

// Append Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

tfhe = { version = "*", features = ["boolean", "shortint", "integer", "x86_64"] }

use tfhe::prelude::*;

use tfhe::{generate_keys, set_server_key, ConfigBuilder, FheUint32, FheUint8};

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

// Basic configuration to use homomorphic integers

let config = ConfigBuilder::default().build();

// Key generation

let (client_key, server_keys) = generate_keys(config);

let clear_a = 1344u32;

let clear_b = 5u32;

let clear_c = 7u8;

// Encrypting the input data using the (private) client_key

// FheUint32: Encrypted equivalent to u32

let mut encrypted_a = FheUint32::try_encrypt(clear_a, &client_key)?;

let encrypted_b = FheUint32::try_encrypt(clear_b, &client_key)?;

// FheUint8: Encrypted equivalent to u8

let encrypted_c = FheUint8::try_encrypt(clear_c, &client_key)?;

// On the server side:

set_server_key(server_keys);

// Clear equivalent computations: 1344 * 5 = 6720

let encrypted_res_mul = &encrypted_a * &encrypted_b;

// Clear equivalent computations: 6720 >> 5 = 210

encrypted_a = &encrypted_res_mul >> &encrypted_b;

// Clear equivalent computations: let casted_a = a as u8;

let casted_a: FheUint8 = encrypted_a.cast_into();

// Clear equivalent computations: min(210, 7) = 7

let encrypted_res_min = &casted_a.min(&encrypted_c);

// Operation between clear and encrypted data:

// Clear equivalent computations: 7 & 1 = 1

let encrypted_res = encrypted_res_min & 1_u8;

// Decrypting on the client side:

let clear_res: u8 = encrypted_res.decrypt(&client_key);

assert_eq!(clear_res, 1_u8);

Ok(())

}

In this example, we initialize the configuration for homomorphic encryption, generate keys, and then encrypt plaintext values. We perform homomorphic multiplication, bitwise shifts, casting, and minimum operations on the encrypted values, followed by decryption to retrieve the final result. This demonstrates secure computation with homomorphic encryption.

In conclusion, privacy-preserving techniques in federated learning, such as differential privacy and homomorphic encryption, offer robust solutions for protecting individual data during model training. While these methods present various trade-offs between privacy and utility, their implementation in Rust showcases the potential for developing efficient and secure federated learning systems. The challenges associated with these techniques, including computational overhead and the need for careful calibration of privacy parameters, underscore the importance of continued research and development in this critical area of machine learning.

24.3. Communication Efficiency in Federated Learning

In Federated Learning (FL), communication efficiency is a critical factor in ensuring the viability and effectiveness of the distributed training process, particularly as the number of participating clients increases. The foundational concept of FL lies in enabling collaborative machine learning across decentralized data sources, allowing data privacy to be maintained by keeping the data localized on client devices. However, as the number of clients grows, the amount of data exchanged between clients and the central server can escalate significantly, leading to increased communication overhead. This overhead can manifest as higher latency, increased computational costs, and bandwidth constraints, all of which can undermine the overall performance and scalability of the system. Consequently, addressing communication efficiency is paramount to making FL systems practical for real-world applications.

One of the key strategies to reduce communication overhead in FL is model compression. The objective of model compression is to minimize the size of the model updates that need to be transmitted from clients to the central server during the training process. Formally, let $\theta \in \mathbb{R}^p$ represent the model parameters of a machine learning model, where $p$ is the number of parameters. In traditional FL, after training on their local data, each client sends the updated model parameters $\theta_j$ back to the server. When $p$ is large, as is often the case in deep learning models, transmitting these full updates from each client leads to substantial communication costs. Model compression techniques seek to reduce the dimensionality or sparsity of $\theta_j$, thereby decreasing the size of the updates. Techniques such as weight pruning, in which insignificant or redundant parameters are removed, can reduce the number of parameters $p'$ that need to be transmitted, where $p' < p$. By sending only the pruned model, communication costs are significantly reduced while retaining the essential structure of the model.

Another prominent method for enhancing communication efficiency is quantization. Quantization involves reducing the precision of the model parameters, thus lowering the amount of data that must be transmitted during the FL process. Let $\theta_j$ represent the local model updates from client $j$, where each element $\theta_{ji} \in \mathbb{R}$ is a floating-point number. In quantization, the floating-point representation of $\theta_{ji}$ is approximated by a lower-precision format, such as an integer. Mathematically, this can be expressed as:

$$ \hat{\theta}_{ji} = \text{Quantize}(\theta_{ji}) = \left\lfloor \frac{\theta_{ji}}{\Delta} \right\rfloor \Delta $$

where $\Delta$ is the quantization step size, and $\hat{\theta}_{ji}$ represents the quantized version of the original parameter $\theta_{ji}$. By reducing the precision from, for example, 32-bit floating-point numbers to 8-bit integers, the amount of data that needs to be communicated between clients and the server is significantly reduced. The trade-off here is between the reduced communication cost and the potential loss of accuracy due to the lower precision representation. However, various adaptive quantization techniques can mitigate this trade-off by adjusting the quantization levels based on the importance of the parameters or the sensitivity of the model to quantization errors.

Sparsification is another crucial technique employed to enhance communication efficiency in FL. In sparsification, instead of transmitting the full set of model updates, clients send only the most significant updates, effectively ignoring smaller or less impactful changes in the parameters. Let $g_j = \theta_j - \theta_{\text{global}}$ represent the gradient of the model update for client $j$, where $\theta_{\text{global}}$ is the current global model. Sparsification involves sending only a subset $S_j \subset g_j$, where the elements in $S_j$are selected based on their magnitudes. Specifically, clients can set a threshold $\tau$ and send only the updates $g_{ji}$ for which $|g_{ji}| > \tau∣$. Formally, the sparsified update is given by:

$$ S_j = \{ g_{ji} : |g_{ji}| > \tau \} $$

By transmitting only the most significant gradients, sparsification reduces the communication cost while preserving the updates that have the most substantial impact on the global model. This approach is particularly effective when combined with techniques such as gradient accumulation, where small updates are accumulated locally over several iterations before being transmitted.

Collectively, these strategies—model compression, quantization, and sparsification—not only reduce the communication burden in federated learning but also contribute to building more scalable and robust systems. By decreasing the size of the updates transmitted between clients and the server, FL can accommodate a larger number of clients with diverse computational and network resources. Moreover, these techniques allow FL to be deployed in environments with limited bandwidth, such as mobile networks or IoT devices, where communication efficiency is paramount.

In practice, implementing these techniques in a federated learning system involves carefully balancing the trade-offs between communication efficiency and model accuracy. While model compression, quantization, and sparsification can significantly reduce the volume of data exchanged, they can also introduce errors or degrade the performance of the global model if not applied judiciously. For instance, excessive pruning or overly aggressive quantization may result in the loss of important model parameters, leading to poor convergence or suboptimal performance. Therefore, a key area of research in FL is the development of adaptive techniques that dynamically adjust the degree of compression, quantization, or sparsification based on the current state of the model and the network conditions.

In conclusion, communication efficiency is a cornerstone of federated learning systems, particularly as they scale to accommodate a large number of clients. By employing techniques such as model compression, quantization, and sparsification, federated learning systems can reduce communication overhead, enhance scalability, and maintain model performance across distributed environments. These techniques are essential for making FL a practical and viable approach for machine learning in privacy-preserving and resource-constrained settings. As federated learning continues to evolve, further advancements in communication efficiency will play a pivotal role in shaping the future of decentralized machine learning.

Implementing communication-efficient Federated Learning in Rust involves a combination of thoughtful design and practical coding techniques. To illustrate these concepts, consider a simplified example where we employ model compression through weight pruning and quantization. We begin by defining a simple neural network model using a hypothetical Rust machine learning library. The following code snippet demonstrates the setup of a basic model and the implementation of a pruning function that reduces the number of parameters based on a predetermined sparsity level.

struct NeuralNetwork {

weights: Vec<f32>, // Simplified representation of weights

}

impl NeuralNetwork {

fn prune_weights(&mut self, sparsity: f32) {

let threshold = self.weights.iter().copied().fold(0.0, f32::max) * sparsity;

self.weights.retain(|&weight| weight.abs() > threshold);

}

fn quantize_weights(&mut self, bits: usize) {

let scale = 2f32.powi(bits as i32) - 1.0;

self.weights.iter_mut().for_each(|weight| {

*weight = (*weight * scale).round() / scale;

});

}

}

fn main() {

let mut nn = NeuralNetwork {

weights: vec![0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5],

};

nn.prune_weights(0.6); // Prune weights to retain only the top 40%

nn.quantize_weights(4); // Quantize weights to 4-bit representation

println!("{:?}", nn.weights);

}

In this example, we define a NeuralNetwork struct containing a vector of weights. The prune_weights method reduces the number of weights based on a specified sparsity level, while the quantize_weights method adjusts the precision of the weights to a specified bit length. After applying these techniques, the model size is significantly reduced before transmitting updates to the central server.

Next, we need to assess the trade-offs between communication cost and model accuracy. While pruning and quantizing weights can lead to substantial reductions in data transmitted, they may also impact the model's performance. Therefore, it is crucial to evaluate the model's accuracy after implementing these techniques. We can simulate this evaluation by training the model on a dataset and calculating the accuracy before and after compression techniques are applied.

fn evaluate_model_accuracy(model: &NeuralNetwork, dataset: &[f32]) -> f32 {

// Placeholder function to simulate model evaluation

// In a real scenario, this would involve making predictions and checking against labels

let accuracy = dataset.iter().map(|&data| {

// Imagine some computation here that uses the model to classify the data

if data > 0.3 { 1.0 } else { 0.0 }

}).collect::<Vec<_>>();

accuracy.iter().sum::<f32>() / accuracy.len() as f32

}

fn main() {

// Previous model and pruning/quantization code...

let dataset = vec![0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6]; // Example dataset

let original_accuracy = evaluate_model_accuracy(&nn, &dataset);

println!("Model accuracy after compression: {:.2}%", original_accuracy * 100.0);

}

In this evaluation function, we simulate the accuracy assessment of the model against a sample dataset. The placeholder logic indicates how a real evaluation might be structured, where predictions are made and compared to true labels. This step is essential for understanding the impact of communication-efficient techniques on the model's overall performance.

In conclusion, enhancing communication efficiency in Federated Learning is paramount, particularly as the number of clients grows and bandwidth becomes a limiting factor. By leveraging model compression, quantization, and sparsification techniques, we can significantly reduce the communication overhead while maintaining model accuracy. The Rust implementation provided in this chapter serves as a foundational example of how these concepts can be applied in practice, demonstrating the balance between efficient communication and effective model training. The ongoing exploration of these strategies will undoubtedly contribute to the evolution of Federated Learning systems, making them more robust and efficient in real-world applications.

24.4. Security Challenges in Federated Learning

Federated Learning (FL) offers an innovative framework for training machine learning models across decentralized devices while ensuring that sensitive data remains localized. By keeping data on the client side, FL significantly enhances privacy, making it a compelling solution for privacy-preserving machine learning. However, the distributed nature of FL introduces a range of security vulnerabilities that must be addressed to ensure the integrity and confidentiality of the training process. These security challenges, if not properly mitigated, can lead to model degradation, data breaches, and a compromise of the overall system's utility. In this section, we explore the fundamental, conceptual, and practical aspects of security risks in Federated Learning, and discuss strategies, including Rust implementations, for mitigating these risks.

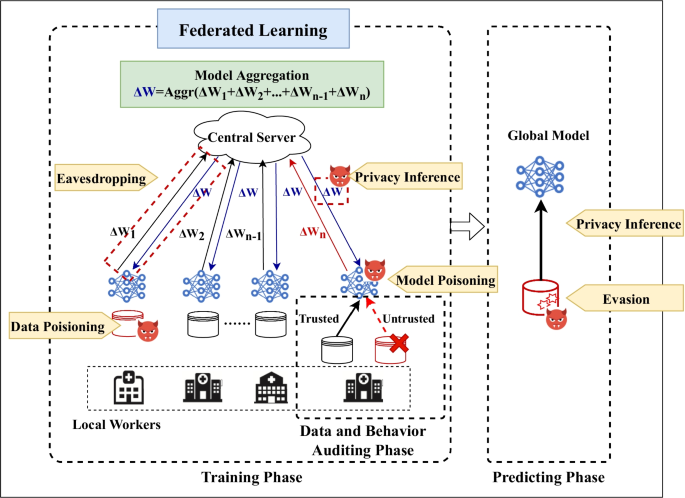

Figure 3: Threats, attacks and defense on federated learning. W is model parameter in this picture.

One of the most prominent security risks in Federated Learning is the threat of poisoning attacks. In a poisoning attack, a malicious participant manipulates the local model updates it submits to the central server with the intent of degrading the overall performance of the global model. Let $f_{\theta}(x)$ represent the global model with parameters $\theta$. Each client $j \in \mathcal{C}$, where $\mathcal{C}$ represents the set of clients, trains a local model $f_{\theta_j}(x)$ on its dataset $D_j$ and sends its model update $\theta_j$ to the server. In a poisoning attack, a compromised client $j'$ sends a manipulated update $\theta_{j'}^*$, which is designed to mislead the aggregation process. The global model update is given by:

$$ \theta_{\text{global}} = \frac{1}{k} \sum_{j=1}^k \theta_j $$

where $k$ is the number of participating clients. If $\theta_{j'}^*$ deviates significantly from the correct update, the global model $\theta_{\text{global}}$ can be skewed, leading to degraded performance. In targeted poisoning attacks, the adversary may seek to degrade performance on specific tasks or inputs, introducing biases that compromise the integrity of the model. Defending against poisoning attacks often involves robust aggregation techniques such as Byzantine-resilient methods, which limit the influence of outlier updates. Mathematically, one approach to mitigating poisoning attacks is to replace the standard averaging process with robust aggregation techniques such as median or trimmed mean aggregation:

$$ \theta_{\text{global}} = \text{Median}(\{\theta_j\}_{j=1}^k) $$

By using median aggregation, the system can reduce the impact of extreme or anomalous updates, thereby mitigating the effect of poisoning attacks.

Another significant security vulnerability in Federated Learning is the risk of inference attacks. In these attacks, an adversary attempts to infer sensitive information about the training data by analyzing model updates or the behavior of the global model. In a typical FL scenario, the model parameters $\theta$ are updated based on the gradients computed on the local data $D_j$. If an adversary has access to the updates $\theta_j$, they can potentially infer sensitive information about the underlying dataset. For instance, consider a classification model $f_{\theta}(x)$ trained on medical data. By examining the gradients of the model updates, an adversary might infer information about specific individuals' health records. This is particularly dangerous in situations where the updates are sparse or where the local data distribution is skewed, making it easier to infer details about individual data points.

Formally, let $\nabla_{\theta} \mathcal{L}(D_j, \theta)$ denote the gradient of the loss function with respect to the model parameters for the local dataset $D_j$. An adversary analyzing the gradients may use techniques such as gradient inversion to reconstruct the input data $x_{ij}$ from the gradients. One defense against inference attacks is to use differential privacy, where noise is added to the updates before they are transmitted to the server. Mathematically, let $\eta$ represent the noise sampled from a distribution such as the Laplace or Gaussian distribution. The differentially private update is given by:

$$\theta_j^* = \theta_j + \eta$$

This noise ensures that the updates are no longer directly linked to the individual data points, thereby protecting against inference attacks. The trade-off, however, is that adding noise can degrade model performance, so it is crucial to balance privacy with utility using methods such as the moments accountant to track cumulative privacy loss over time.

Model inversion attacks represent another serious threat to Federated Learning. In a model inversion attack, the adversary seeks to reconstruct the input data $x$ from the model’s outputs or gradients. Let $f_{\theta}(x)$ represent a trained model with parameters $\theta$. In a model inversion attack, the adversary attempts to recover an approximation $\hat{x}$ of the input $x$ by exploiting the information in the model’s predictions. This is particularly dangerous in settings where the model is trained on sensitive data, such as healthcare or financial records. Model inversion attacks are particularly effective when the adversary has access to both the model and its outputs over a range of inputs.

One way to mitigate the risk of model inversion attacks is to implement secure aggregation techniques that prevent the server from learning the individual updates from clients. In secure aggregation, the server only receives an encrypted or masked version of the updates, which it can aggregate without learning the raw updates from each client. Formally, let $\theta_j^*$ represent the masked update from client $j$. The server computes the aggregate update:

$$ \theta_{\text{global}} = \frac{1}{k} \sum_{j=1}^k \theta_j^* $$

without ever seeing the individual $\theta_j^*$. Techniques such as homomorphic encryption and secure multi-party computation (MPC) can be employed to implement secure aggregation. Homomorphic encryption allows the server to compute the aggregate update on encrypted data without needing to decrypt it, thereby ensuring that individual updates remain private. MPC, on the other hand, enables multiple parties to collaboratively compute a function over their inputs without revealing their inputs to one another, thereby safeguarding against model inversion.

The decentralized nature of Federated Learning requires that security measures be built into the system architecture from the ground up. Each of these attacks—poisoning attacks, inference attacks, and model inversion attacks—poses a unique challenge that must be addressed through robust security mechanisms. Rust, with its emphasis on safety and performance, provides an ideal platform for implementing these security techniques. Rust’s memory safety guarantees and concurrency features make it well-suited for developing secure and efficient Federated Learning systems that can mitigate these security risks.

In conclusion, the security challenges in Federated Learning are complex and multifaceted. Poisoning attacks threaten the integrity of the model, while inference and model inversion attacks compromise the confidentiality of the training data. To build secure FL systems, it is essential to integrate robust defenses, including Byzantine-resilient aggregation, differential privacy, and secure aggregation techniques. By addressing these security concerns, Federated Learning can maintain its promise of privacy-preserving machine learning while ensuring that the system remains resilient to malicious actors.

To combat these security challenges, practitioners must focus on implementing practical solutions that enhance the resilience of Federated Learning systems. One effective approach is the adoption of anomaly detection techniques to identify and mitigate the impact of poisoned updates. For instance, one could calculate the distance between individual updates and the global model update, rejecting any that exceed a predefined threshold. In Rust, this can be implemented using the ndarray crate, which provides a powerful way to manipulate N-dimensional arrays. Below is an example that demonstrates how to perform anomaly detection by calculating the Euclidean distance between model updates:

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2, Array};

fn detect_anomalies(global_model: &Array1<f64>, local_updates: &Array2<f64>, threshold: f64) -> Vec<bool> {

local_updates.rows().into_iter().map(|update| {

let distance = (&update - global_model).mapv(|x| x.powi(2)).sum().sqrt();

distance < threshold

}).collect()

}

fn main() {

let global_model = Array::from_vec(vec![0.5, 0.2, 0.3]);

let local_updates = Array::from_shape_vec((3, 3), vec![0.5, 0.2, 0.4, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.9, 0.3]).unwrap();

let threshold = 0.2;

let anomalies = detect_anomalies(&global_model, &local_updates, threshold);

println!("Anomaly detection results: {:?}", anomalies);

}

In addition to anomaly detection, employing robust aggregation techniques is another effective measure to bolster security against poisoning attacks. Instead of simply averaging the updates from all participants, more sophisticated methods such as trimmed mean or Krum can be utilized. These techniques help to ensure that the final aggregated update is more representative of the true model, effectively mitigating the influence of outlier updates. Implementing Krum, for example, can be done in Rust as follows:

use ndarray::{Array1, Array2, Array};

fn krum(local_updates: &Array2<f64>, num_participants: usize) -> Array1<f64> {

let mut distances = Array2::<f64>::zeros((num_participants, num_participants));

for i in 0..num_participants {

let row_i = local_updates.row(i).to_owned();

for j in 0..num_participants {

if i != j {

let row_j = local_updates.row(j).to_owned();

distances[[i, j]] = (row_i.clone() - row_j).mapv(|x| x.powi(2)).sum();

}

}

}

// Find the participant with the minimum sum of distances from others

let mut scores: Vec<(usize, f64)> = (0..num_participants)

.map(|i| (i, distances.row(i).sum()))

.collect();

scores.sort_by(|a, b| a.1.partial_cmp(&b.1).unwrap());

// Return the update from the participant with the minimum distance

local_updates.row(scores[0].0).to_owned()

}

fn main() {

let local_updates = Array::from_shape_vec((3, 3), vec![0.5, 0.2, 0.4, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.9, 0.3]).unwrap();

let aggregated_update = krum(&local_updates, 3);

println!("Krum aggregated update: {:?}", aggregated_update);

}

Finally, ensuring the security of model updates during transmission is vital. Techniques such as secure multiparty computation (SMPC) or homomorphic encryption can be employed to ensure that participants can compute updates without revealing their private data. While implementing these advanced cryptographic techniques can be complex, utilizing Rust's strong type system and memory safety features can significantly mitigate risks associated with security vulnerabilities.

In conclusion, security challenges in Federated Learning are a multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive understanding of various attack vectors. By implementing robust security measures such as anomaly detection, secure aggregation techniques, and secure model updates, we can enhance the resilience of Federated Learning systems. As we continue to explore and innovate within the realm of machine learning, it is imperative to prioritize security to protect sensitive data while reaping the benefits of collaborative learning.

24.5. Federated Learning in Edge Computing and IoT

The advent of edge computing and the proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices have fundamentally reshaped the data generation and processing landscape. IoT devices, ranging from smartphones and wearable technology to sensors in industrial and healthcare environments, continuously produce vast amounts of data at the edge of the network. This decentralized nature of data generation presents a significant challenge in terms of privacy, security, and the sheer volume of data that would need to be transferred to centralized servers for processing. Federated Learning (FL) offers a compelling solution to this challenge by allowing machine learning models to be collaboratively trained across decentralized devices while ensuring that raw data never leaves the local device. In this section, we explore the role of Federated Learning in edge computing and IoT, the inherent challenges of deploying FL on resource-constrained devices, and practical implementations using Rust.

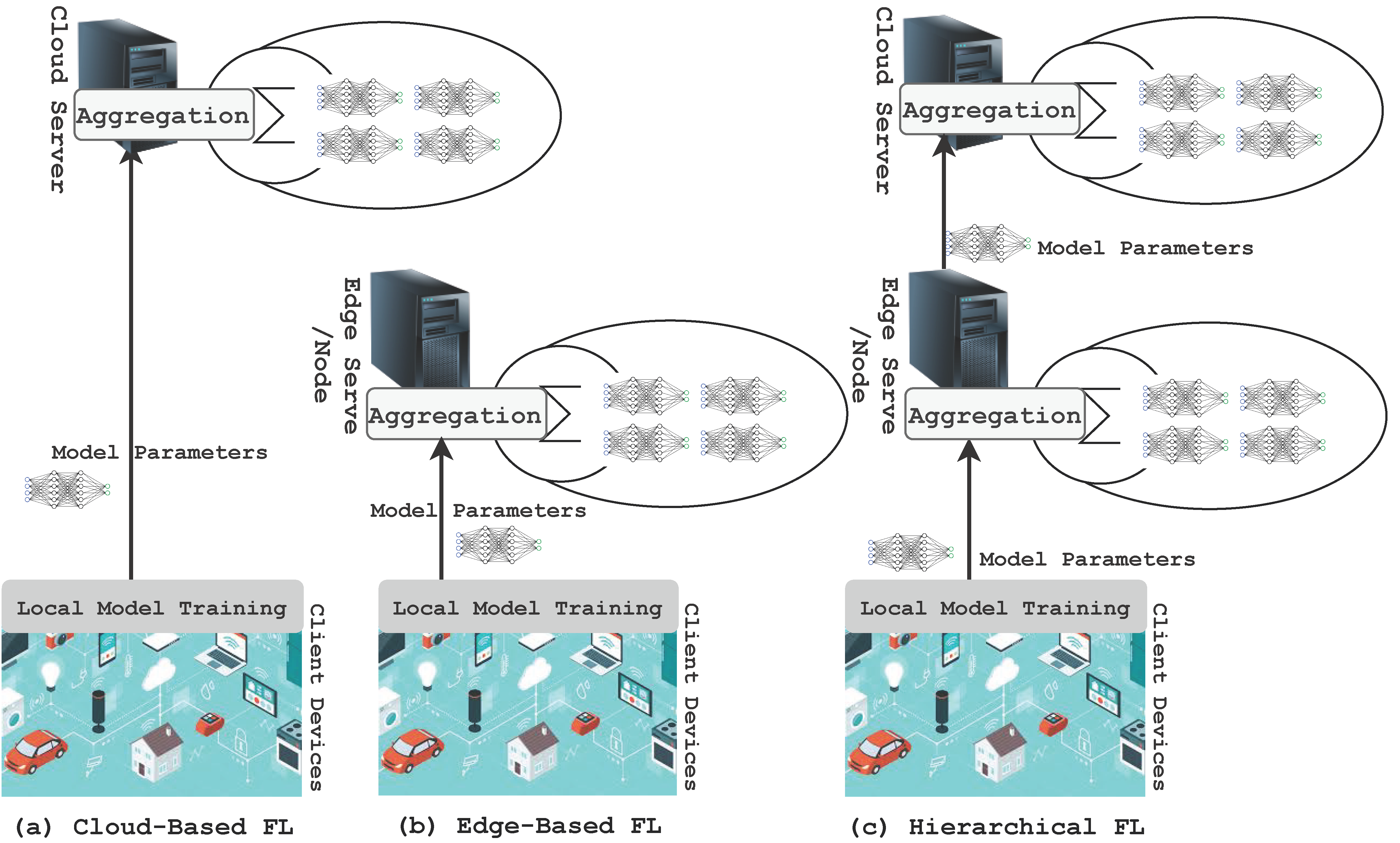

Figure 4: Illustration of federated learning in edge computing and IoT.

At the core of Federated Learning is the concept of collaborative learning, where multiple devices contribute to the training of a global model while keeping their respective training data localized. Formally, let $\mathcal{C} = \{C_1, C_2, \dots, C_k\}$ represent a set of $k$ edge devices or IoT nodes, each possessing a local dataset $D_j = \{(x_{ij}, y_{ij})\}_{i=1}^{n_j}$. Instead of aggregating all local datasets at a central server, each device $C_j$ trains a local model $f_{\theta_j}(x)$ on its own dataset $D_j$. After training, the local model parameters $\theta_j$ are sent to a central server, where they are aggregated to update a global model $f_{\theta_{\text{global}}}(x)$. The most common aggregation technique is Federated Averaging (FedAvg), which computes the global model as:

$$ \theta_{\text{global}} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=1}^k n_j \theta_j $$

where $n = \sum_{j=1}^k n_j$ is the total number of data points across all devices. This process allows edge devices to participate in the training of a global model while retaining their local data, thereby addressing privacy concerns and reducing the latency and bandwidth costs associated with sending raw data to a central server. This is particularly beneficial in IoT environments, where data can be highly sensitive, such as health records collected by wearable devices or location data from smart sensors. Federated Learning ensures that these sensitive datasets remain local, thereby enhancing compliance with data privacy regulations like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

While Federated Learning offers substantial advantages in terms of privacy and communication efficiency, deploying FL in edge and IoT environments introduces a number of technical challenges. Many IoT devices are resource-constrained, with limited processing power, memory, and battery life. This poses a significant challenge when attempting to train machine learning models, particularly complex deep learning models, on such devices. Let $p$ denote the number of parameters in the model $\theta_j$. If $p$ is large, as is often the case in deep learning models, the computational and memory demands can quickly exceed the capabilities of typical IoT devices. Therefore, it is crucial to employ techniques that reduce the computational burden while maintaining acceptable levels of model performance.

One approach to addressing this challenge is model pruning, which reduces the size of the model by removing parameters that contribute minimally to the final prediction. Let $f_{\theta}$ be a model with parameters $\theta \in \mathbb{R}^p$. In model pruning, the goal is to find a subspace $\theta' \subset \theta$, where $\text{dim}(\theta') < p$, that approximates the original model's performance. This can be formulated as the following optimization problem:

$$ \theta' = \arg \min_{\theta'} \mathcal{L}(f_{\theta'}(x), y) \quad \text{subject to} \quad \|\theta'\|_0 \leq k $$

where $\mathcal{L}$ is the loss function, and $k$ is the desired number of parameters after pruning. By transmitting only the pruned model $\theta'$, we reduce the computational load on the edge device and minimize the amount of data transmitted back to the server, thereby enhancing both computation and communication efficiency.

Another effective technique is quantization, which reduces the precision of the model parameters. Consider a model update $\theta_j \in \mathbb{R}^p$, where each parameter $\theta_{ji}$ is represented as a floating-point number. In quantization, each $\theta_{ji}$ is approximated by a lower-precision value, such as an 8-bit integer, rather than a 32-bit floating-point number. Mathematically, this is represented as:

$$ \hat{\theta}_{ji} = \text{Quantize}(\theta_{ji}) = \left\lfloor \frac{\theta_{ji}}{\Delta} \right\rfloor \Delta $$

where $\Delta$ is the quantization step size. By reducing the precision, we not only decrease the memory footprint of the model on resource-constrained devices but also reduce the bandwidth required to transmit model updates. However, quantization introduces a trade-off between model accuracy and communication efficiency, as overly aggressive quantization can result in a loss of model performance.

Knowledge distillation is another technique that can be employed to reduce the complexity of models deployed on edge devices. In knowledge distillation, a large and complex model (the teacher) is trained centrally, and its knowledge is transferred to a smaller, more efficient model (the student) that is deployed on the edge device. Formally, let $f_{\theta_{\text{teacher}}}(x)$ represent the teacher model and $f_{\theta_{\text{student}}}(x)$ the student model, where $\theta_{\text{student}} \in \mathbb{R}^{p'}$ with $p' < p$. The goal is to minimize the discrepancy between the predictions of the teacher and the student by solving the following optimization problem:

$$ \min_{\theta_{\text{student}}} \mathcal{L}(f_{\theta_{\text{student}}}(x), f_{\theta_{\text{teacher}}}(x)) $$

By training a lightweight student model, we ensure that the edge devices can perform local inference and model updates efficiently, while still benefiting from the knowledge distilled from a more powerful teacher model.

In addition to these model efficiency techniques, the asynchronous nature of IoT networks must be considered when deploying Federated Learning. Many IoT devices experience intermittent connectivity due to power constraints, network reliability, or mobility. Therefore, Federated Learning systems must accommodate asynchronous model updates, where devices may upload their local updates at irregular intervals. Mathematically, this can be represented as an asynchronous aggregation of updates, where the global model $\theta_{\text{global}}$ is updated in an online fashion as updates θj\\theta_jθj from individual devices arrive:

$$ \theta_{\text{global}}^{(t+1)} = \theta_{\text{global}}^{(t)} + \eta \sum_{j \in \mathcal{C}} w_j \Delta \theta_j $$

where $\Delta \theta_j$ is the model update from device $j$, $w_j$ is a weighting factor, and $\eta$ is the learning rate. This asynchronous aggregation ensures that the learning process continues even when some devices are offline, improving the robustness and scalability of the FL system.

In conclusion, Federated Learning plays a critical role in edge computing and IoT by enabling collaborative machine learning while preserving data privacy and reducing latency. However, deploying FL on resource-constrained devices requires careful consideration of model efficiency, communication overhead, and asynchronous updates. Techniques such as model pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation are essential for ensuring that the models deployed on edge devices are lightweight and efficient, while asynchronous aggregation allows for resilient training in dynamic IoT environments. Rust, with its focus on performance and system-level control, provides an ideal platform for implementing these techniques and optimizing FL for edge and IoT devices.

In terms of practical implementation, Rust's performance and safety features make it an excellent choice for developing Federated Learning applications for edge devices. Rust's memory safety guarantees help prevent common programming errors, such as buffer overflows, which is particularly important for devices operating in diverse and potentially hostile environments. Below is a simplified example showcasing how one might implement a basic Federated Learning setup in Rust.

First, we define our lightweight model using a simple linear regression as an illustration:

struct LinearModel {

weights: Vec<f32>,

}

impl LinearModel {

fn new(input_size: usize) -> Self {

LinearModel {

weights: vec![0.0; input_size],

}

}

fn train(&mut self, data: &Vec<(Vec<f32>, f32)>, learning_rate: f32) {

for (inputs, target) in data {

let prediction = self.predict(inputs);

let error = target - prediction;

for (i, &input) in inputs.iter().enumerate() {

self.weights[i] += learning_rate * error * input;

}

}

}

fn predict(&self, inputs: &Vec<f32>) -> f32 {

self.weights.iter().zip(inputs.iter()).map(|(w, x)| w * x).sum()

}

}

In this code snippet, we create a simple linear model capable of training on local datasets. The train method adjusts the model weights based on the provided input data and the corresponding target values. The predict method computes predictions based on the current weights and given inputs.

Next, we would need to simulate the federated learning process, where each edge device trains its local model and then shares the updates with a central server. In this example, we will demonstrate how to aggregate model updates from multiple devices:

fn aggregate_updates(updates: Vec<Vec<f32>>) -> Vec<f32> {

let num_updates = updates.len();

let model_size = updates[0].len();

let mut aggregated_weights = vec![0.0; model_size];

for weights in updates {

for (i, &weight) in weights.iter().enumerate() {

aggregated_weights[i] += weight;

}

}

aggregated_weights.iter_mut().for_each(|w| *w /= num_updates as f32);

aggregated_weights

}

The aggregate_updates function takes a vector of model updates (each represented as a vector of weights) and computes the average weight for each parameter. This aggregation step is critical in Federated Learning, where the server combines the contributions from multiple devices to update the global model.

In a real-world application, steps would also include network communication to send updates to and receive the global model from a server. This can be achieved through Rust's networking capabilities, using libraries like tokio for asynchronous communication.

To optimize this implementation for IoT environments, we might consider several strategies. For instance, reducing the frequency of communication by allowing devices to perform multiple local training epochs before sending updates can save bandwidth. Moreover, employing techniques such as differential privacy can further enhance privacy by adding noise to the local updates, ensuring that individual contributions remain confidential.

In conclusion, Federated Learning presents a compelling paradigm for training machine learning models in edge computing and IoT environments. With its emphasis on privacy and efficiency, it aligns well with the needs of resource-constrained devices. By leveraging Rust's robust features, developers can implement effective Federated Learning solutions that balance local computation, model efficiency, and server communication. As the IoT landscape continues to evolve, the role of Federated Learning will undoubtedly grow, providing new opportunities and challenges for machine learning practitioners.

24.6. Applications of Federated Learning

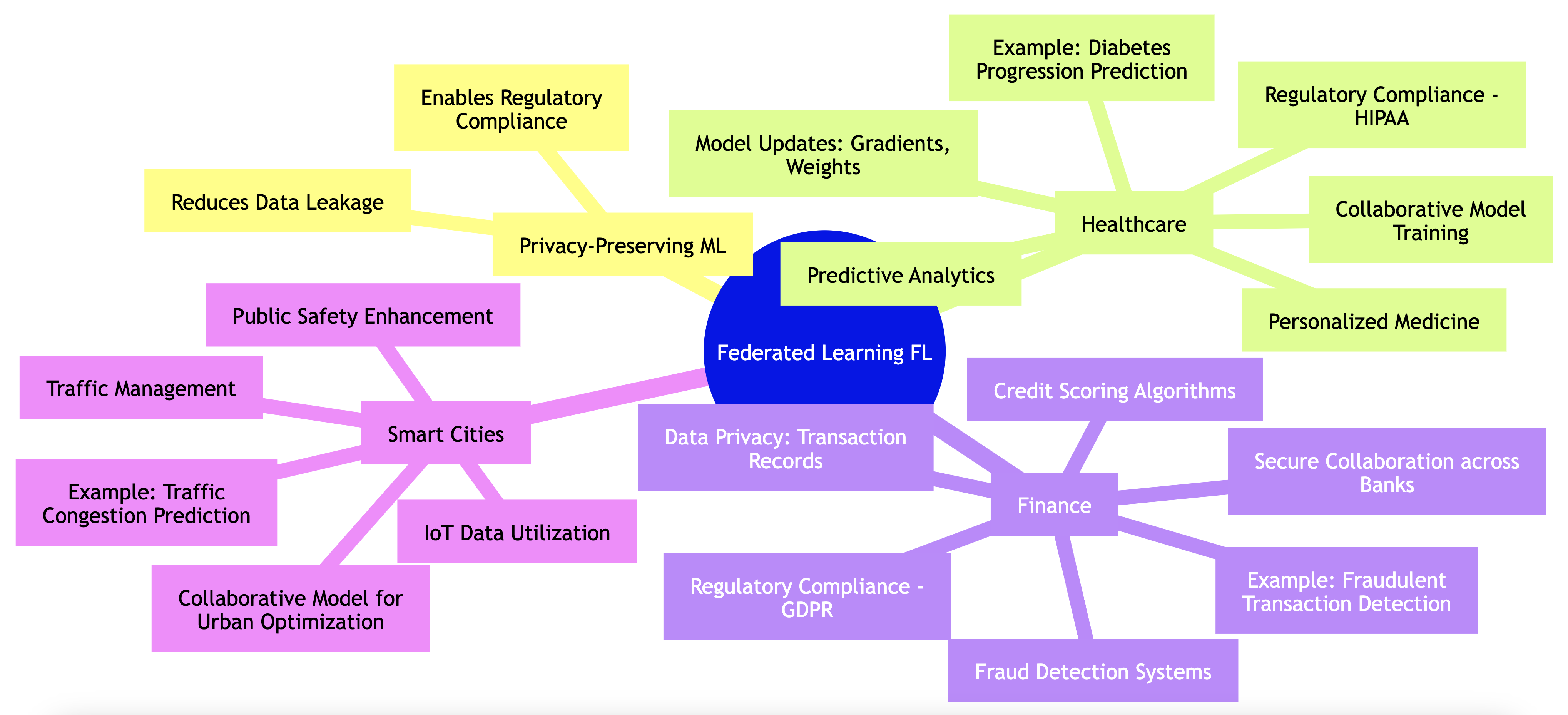

Federated Learning (FL) has gained prominence as a powerful approach to machine learning that directly addresses critical concerns about privacy and regulatory compliance. Traditional machine learning models often require data to be centralized, which increases the risk of data leakage and violates many privacy regulations. FL provides a solution by allowing multiple organizations or parties to collaboratively train a model without having to share their raw data. This decentralization reduces the risk of data exposure, while still enabling the creation of powerful and accurate machine learning models. FL’s applicability spans sectors where data sensitivity is crucial, such as healthcare, finance, and smart cities, each benefiting from the privacy-preserving nature of this technology.

In the healthcare domain, Federated Learning is reshaping how medical data is utilized, enabling predictive analytics and personalized medicine. Traditional methods require centralizing sensitive patient data, which raises concerns under strict regulations such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States. FL allows hospitals and medical institutions to collaboratively train a machine learning model on data like medical images or health records, without transferring this data out of their secure local systems. For example, multiple hospitals can train a model to predict the progression of chronic diseases such as diabetes. Instead of sharing patient records, hospitals only transmit model updates, such as gradients or weights, derived from their local data. These updates are sent to a central server that aggregates the inputs to improve the global model. The key benefit is that the raw data stays within the hospital, ensuring patient privacy and compliance with privacy regulations.

In the financial sector, Federated Learning offers transformative potential for systems like fraud detection and credit scoring, areas where regulatory compliance is stringent under laws like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Financial institutions, such as banks, face challenges in sharing data across organizations due to the highly sensitive nature of transaction records. FL allows banks to collaboratively train machine learning models that can detect fraudulent activities or improve credit scoring models, without exposing their customer transaction data. In this scenario, each bank contributes learned parameters from their local data, which are aggregated into a global model. This approach enhances the accuracy and robustness of the fraud detection system, as the model benefits from diverse datasets, while still protecting customer privacy and adhering to financial regulations.

The smart cities domain presents another compelling use case for Federated Learning. In smart cities, a variety of IoT devices—such as traffic cameras, environmental sensors, and public safety systems—generate vast amounts of decentralized data. These data sources could provide valuable insights to improve urban planning, optimize public services, and enhance citizen safety. However, sharing raw data across city departments, such as traffic management or public safety, raises significant privacy concerns. FL enables these departments to collaboratively train models on their local datasets without sharing the raw data itself. For instance, city traffic systems could use FL to predict and manage traffic congestion, while public safety departments could enhance surveillance and response systems. The result is a collaborative effort that improves city operations while respecting citizen privacy.

Figure 5: Some applications of federated learning models.

While the conceptual benefits of Federated Learning are clear, implementing these systems in Rust poses its own set of challenges and opportunities. The Rust programming language is known for its performance, memory safety, and concurrency features, making it an excellent choice for developing scalable FL systems. As a practical example, let’s explore a simplified implementation of a Federated Learning framework in Rust.

To begin with, one might define the model’s architecture using Rust's machine learning libraries, such as ndarray for numerical computations and tch-rs for deep learning. Here is a basic example of how to set up a federated learning scenario in Rust:

use ndarray::Array;

use ndarray_rand::RandomExt;

use ndarray_rand::rand_distr::Uniform;

use tch::{nn, Device, Tensor};

#[derive(Debug)]

struct SimpleModel {

linear: nn::Linear,

}

impl SimpleModel {

fn new(vs: &nn::Path) -> SimpleModel {

let linear = nn::linear(vs, 1, 1, Default::default());

SimpleModel { linear }

}

fn forward(&self, input: Tensor) -> Tensor {

input.apply(&self.linear)

}

}

// Simulated local training function

fn train_local_model(model: &mut SimpleModel, data: &Array<f32, ndarray::Dim<[usize; 2]>>, targets: &Array<f32, ndarray::Dim<[usize; 1]>>) {

// Implement local training logic here

}

// Function to aggregate model updates from multiple clients

fn aggregate_models(models: Vec<Tensor>) -> Tensor {

let mut sum = models[0].copy(); // Start with the first tensor's values

for model in models.iter().skip(1) {

sum += model; // Accumulate the sum of all tensors

}

// Create a tensor from the scalar value to use in the division

let divisor = Tensor::from(models.len() as f32);

sum / divisor // Average the tensor values

}

fn main() {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::Cpu);

let mut model = SimpleModel::new(&vs.root());

// Simulated local datasets from different clients

let local_data = vec![

Array::random((10, 1), Uniform::new(0.0, 1.0)),

Array::random((10, 1), Uniform::new(0.0, 1.0)),

];

let mut client_models = Vec::new();

for data in local_data.iter() {

let targets = Array::random((10,), Uniform::new(0.0, 1.0));

train_local_model(&mut model, data, &targets);

let tensor_data = Tensor::from_slice(&data.as_slice().unwrap()).view((10, 1)).to(device);

client_models.push(model.forward(tensor_data));

}

let aggregated_model = aggregate_models(client_models);

println!("Aggregated Model: {:?}", aggregated_model);

}

In this simplified model, we define a basic linear model and simulate the local training of several clients. Each client trains their model using local data, and once completed, they send their model updates to a central server, which aggregates the updates. This code serves as a foundational framework, illustrating how one might set up federated learning in Rust, focusing on the collaborative aspect while abstracting the complexities of real-world data handling and model training.

While the advantages of Federated Learning are compelling, it's essential to acknowledge the challenges associated with its deployment. These challenges include ensuring the quality of model updates from clients with limited or unbalanced datasets, maintaining synchronization across various nodes, and dealing with the potential for adversarial attacks. Additionally, achieving compliance with ever-evolving regulations requires a proactive approach to security and privacy measures.

In conclusion, Federated Learning presents a transformative opportunity across various domains, especially in situations where data privacy and compliance are non-negotiable. Rust's performance and safety features provide a robust platform for the development of federated systems, allowing organizations to harness the power of collaborative machine learning while safeguarding individual privacy. As we continue to explore this innovative approach, it will be crucial to remain vigilant about the associated challenges and seek solutions that enhance both the effectiveness and security of Federated Learning implementations.

24.7. Regulatory and Ethical Considerations in Federated Learning

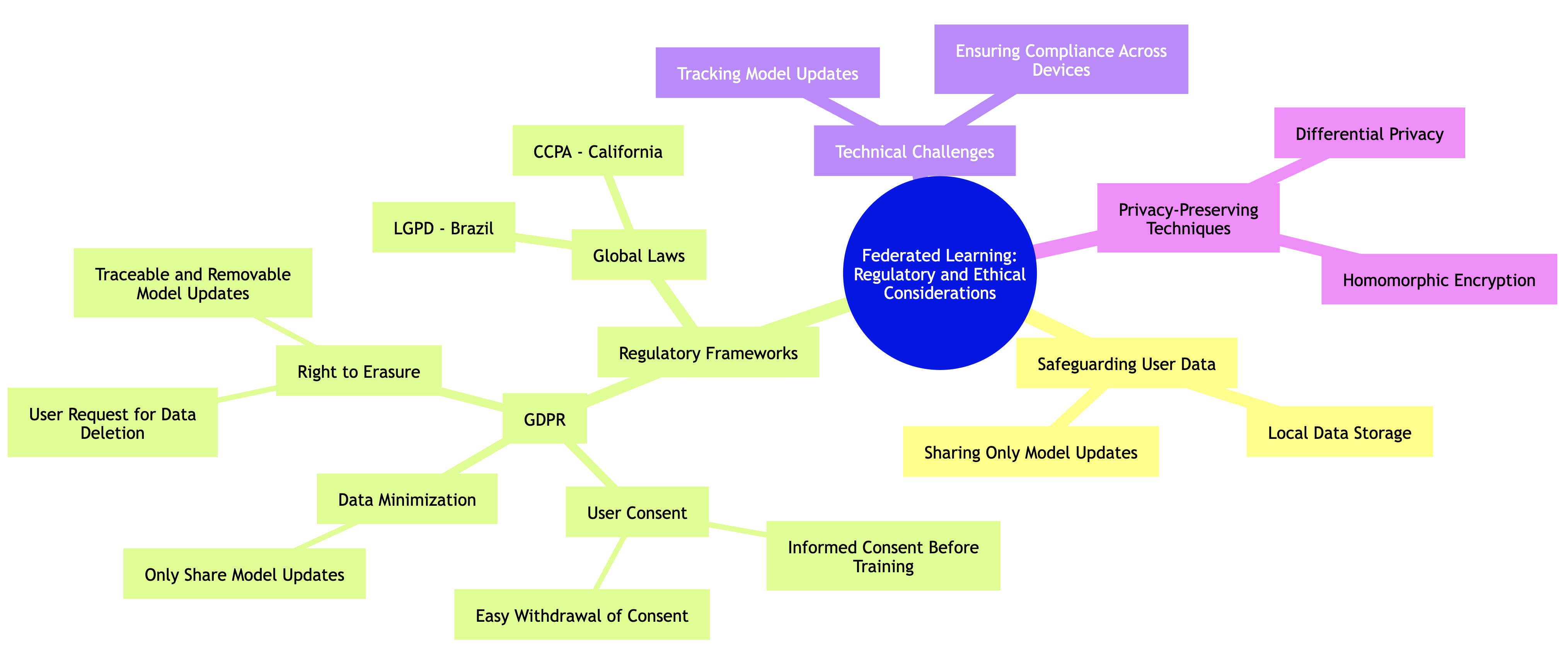

Federated learning offers a promising solution to privacy challenges in machine learning by keeping data localized on user devices, significantly reducing the risk of exposing sensitive information. However, despite its decentralized nature, federated learning introduces new regulatory and ethical responsibilities that must be addressed, particularly in light of frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and similar laws worldwide. These laws impose stringent requirements for handling personal data, ensuring that user rights are respected and data protection principles are upheld.

Figure 6: Scopes of regulatory and ethical consideration of federated learning.

A central tenet of the GDPR is the necessity for user consent. In the context of federated learning, this means that before any data is used to train a model—even though the data remains on the user's device—developers must obtain explicit consent from users. This consent must be informed, meaning users need to fully understand how their data will be used in the training process, and it should be as simple as possible for users to grant or deny permission. Federated learning systems need to incorporate mechanisms for users to easily provide or withdraw consent at any time, particularly given the GDPR's principle of data minimization. This principle asserts that only the minimum amount of data necessary should be used, and in the case of federated learning, only the model updates (such as gradients or weights) are shared with the central server, while the raw data stays on the local device.

Another critical GDPR consideration in federated learning is the right to erasure, also known as the "right to be forgotten." This right entitles users to request the deletion of their personal data. Even though federated learning systems do not share raw data, developers must ensure that users can exercise this right. For example, if a user withdraws consent, any model updates derived from their data must be traceable and removable from the global model, ensuring full compliance with the regulation. Implementing systems that can track and manage these model updates across a decentralized network introduces a significant technical challenge but is essential for upholding user rights under data protection laws.

In addition to GDPR, other regulatory frameworks across the globe, such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and Brazil's General Data Protection Law (LGPD), have similar provisions that must be considered when deploying federated learning. These laws emphasize not just data privacy but also accountability, ensuring that organizations remain transparent about how data is used and processed, even in decentralized learning environments. As federated learning continues to evolve, integrating privacy-preserving techniques such as differential privacy and homomorphic encryption into these systems will be crucial for enhancing data security and ensuring compliance with global regulatory standards.

In Rust, implementing a federated learning framework that complies with GDPR requires careful attention to data handling and user consent mechanisms. Below is an example that outlines how one might begin structuring a federated learning framework that incorporates user consent management within a Rust application:

// Append Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

serde = { version = "1.0.210", features = ["derive"] }

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

use std::collections::HashMap;

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize)]

struct UserConsent {

user_id: String,

consent_given: bool,

}

struct FederatedLearningFramework {

user_consent: HashMap<String, UserConsent>,

}

impl FederatedLearningFramework {

fn new() -> Self {

FederatedLearningFramework {

user_consent: HashMap::new(),

}

}

fn give_consent(&mut self, user_id: String) {

let consent = UserConsent {

user_id: user_id.clone(),

consent_given: true,

};

self.user_consent.insert(user_id, consent);

}

fn withdraw_consent(&mut self, user_id: &String) {

if let Some(consent) = self.user_consent.get_mut(user_id) {

consent.consent_given = false;

}

}

fn is_consent_given(&self, user_id: &String) -> bool {

self.user_consent.get(user_id).map_or(false, |c| c.consent_given)

}

}

In this example, we create a simple structure for managing user consent within a federated learning framework. The UserConsent struct captures whether a user has granted permission for their data to be used. The FederatedLearningFramework struct holds a collection of user consents, allowing the framework to check if consent is given before proceeding with model training.