Chapter 25

Ethics and Fairness in Machine Learning

"The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool." — Richard Feynman

Chapter 25 of MLVR explores the critical issues of Ethics and Fairness in Machine Learning, providing a comprehensive framework for developers to build ethical AI systems using Rust. The chapter begins by laying the groundwork for understanding the ethical principles that guide AI development, emphasizing the need to consider the broader societal impacts of AI. It then delves into the sources and types of bias in machine learning, offering practical strategies for identifying and mitigating bias in data and models. Fairness metrics are discussed in detail, providing developers with the tools to evaluate and ensure fairness in their models. Transparency and explainability are highlighted as essential components of ethical AI, with practical techniques for making AI models more interpretable and accountable. The chapter also addresses the importance of accountability and privacy, offering solutions for ensuring that AI systems are both responsible and secure. Real-world case studies provide insights into the challenges and solutions in ethical AI, and the chapter concludes with a look at the future of ethical AI, encouraging developers to stay informed and proactive in addressing emerging ethical issues. By the end of this chapter, readers will have a deep understanding of how to implement ethical and fair machine learning practices using Rust, ensuring that their AI systems are not only effective but also aligned with the highest ethical standards.

25.1. Introduction to Ethics and Fairness in Machine Learning

As machine learning (ML) becomes deeply integrated into diverse areas of society, the ethical implications and considerations of fairness in algorithmic decision-making have garnered increasing attention. Machine learning algorithms influence many facets of life, from healthcare and finance to education and criminal justice. The decisions made by these algorithms can significantly affect individuals and communities, highlighting the importance of addressing ethics and fairness in AI systems. Without a deliberate and thoughtful approach, ML systems can unintentionally perpetuate biases, invade personal privacy, and lead to outcomes that are unfair or unjust.

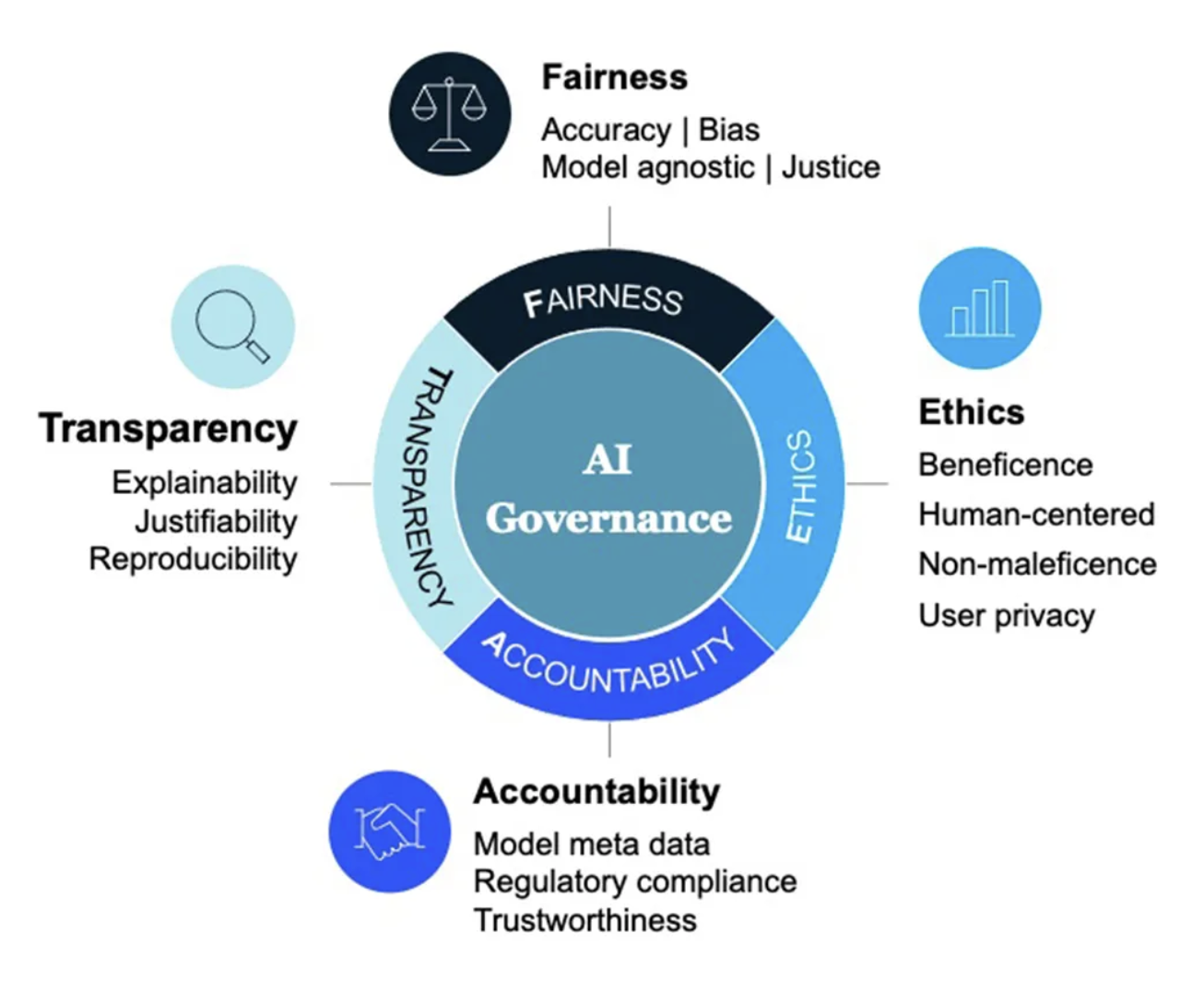

Figure 1: AI Governance FEAT framework (Fairness, Ethics, Accountability, and Transparency).

To address these concerns, the AI Governance framework FEAT—which stands for Fairness, Ethics, Accountability, and Transparency—provides guiding principles for responsible AI development. Fairness ensures that machine learning models do not reinforce harmful biases or disproportionately impact certain groups. Ethics promotes moral decision-making within AI systems, safeguarding personal rights and privacy. Accountability holds developers and organizations responsible for the outcomes of AI systems, ensuring that there is a clear understanding of how decisions are made. Lastly, Transparency emphasizes openness in AI development, making models and their decision processes understandable and accessible to the public.

These FEAT principles form the foundation of ethical AI development, ensuring that the benefits of machine learning are distributed equitably across society while safeguarding against potential harm. By adopting frameworks like FEAT, organizations can ensure their AI systems align with societal values and promote inclusivity, fairness, and trust in AI technologies.

The philosophical underpinnings of ethical frameworks offer valuable insight into how ethical principles can be applied to the development of machine learning systems. One prominent ethical framework is utilitarianism, which advocates for decisions that maximize overall happiness or societal benefit while minimizing harm. In the context of machine learning, this framework suggests that developers should consider the broader societal impact of their models, aiming to design systems that improve welfare and reduce negative consequences. Formally, let $U(x)$ be a utility function representing the societal benefit of an outcome $x$, where the goal is to maximize $U(x)$ across all potential outcomes. The optimization problem from a utilitarian perspective can be expressed as:

$$ \max_{\theta} \sum_{x} P(x \mid \theta) U(x) $$

where $\theta$ represents the model parameters and $P(x \mid \theta)$ is the probability of outcome $x$ given the model $f_{\theta}$. Utilitarianism thus provides a framework for weighing the societal benefits of different model decisions, encouraging developers to optimize for overall positive impact while minimizing harm.

Another significant ethical framework is deontology, which emphasizes adherence to rules, duties, and rights, rather than focusing solely on outcomes. In the context of machine learning, deontology stresses the importance of ensuring that individual rights are respected and that fairness is maintained in decision-making processes. This approach is particularly relevant in scenarios where algorithms are used to make high-stakes decisions, such as in hiring, credit scoring, or legal judgments. A deontological approach to machine learning requires that developers establish rules and constraints to ensure that their models do not discriminate or violate the rights of individuals. Mathematically, fairness constraints can be formalized in machine learning models by ensuring that the probability of a positive outcome is independent of sensitive attributes such as race, gender, or socioeconomic status. For instance, demographic parity can be expressed as:

$$ P(f(x) = 1 \mid A = a) = P(f(x) = 1 \mid A = b) \quad \forall a, b \in A $$

where $f(x)$ is the machine learning model, and $A$ represents a sensitive attribute. Deontological principles require that these constraints be integrated into the model design to ensure fairness across all groups.

Virtue ethics, a third philosophical framework, focuses on the character and intentions of the developers themselves rather than the outcomes or rules governing the model. This framework encourages developers to cultivate virtues such as honesty, fairness, and empathy in the development of machine learning systems. The emphasis here is on the moral responsibility of the individuals and teams designing the algorithms. By fostering an ethical mindset and culture within development teams, virtue ethics ensures that ethical considerations permeate every stage of the machine learning lifecycle. This includes decisions about data collection, model design, and the interpretation of model outputs.

In practice, integrating these philosophical frameworks into Rust-based machine learning projects requires a multi-faceted approach that embeds ethical considerations into the core of the development process. Rust, known for its strong emphasis on performance, memory safety, and system-level control, offers an ideal environment for building machine learning models that are not only efficient but also aligned with ethical standards. A critical step in developing ethical AI systems is conducting bias audits on datasets. Formally, bias can be detected by measuring disparities in model performance across different demographic groups. For instance, let $D = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^n$ represent a training dataset, where $x_i$ includes sensitive attributes such as race or gender. A bias audit involves analyzing the model’s error rates or predictions across these groups to identify disparities. The fairness metric ΔE\\Delta EΔE can be defined as the difference in error rates between two groups:

$$ \Delta E = |E(f_{\theta}(x) \mid A = a) - E(f_{\theta}(x) \mid A = b)| $$

where $E$ represents the error rate, and $A$ is a sensitive attribute. Ensuring that $\Delta E$ remains within acceptable bounds is a key part of mitigating bias and ensuring fairness in the model’s predictions.

Another crucial aspect of ethical AI development is promoting transparency and accountability in machine learning systems. Transparency involves making the decision-making process of the model interpretable and understandable to users and stakeholders. One way to achieve transparency is by implementing interpretable models, such as decision trees or linear models, where the relationship between inputs and outputs is easily understood. Alternatively, post-hoc explainability techniques, such as SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations), can be employed to explain the outputs of more complex models. SHAP values assign an importance score to each feature based on its contribution to the model’s prediction:

$$ \phi_j(f, x) = \sum_{S \subseteq N \setminus \{j\}} \frac{|S|!(n - |S| - 1)!}{n!} \left(f(x_S \cup \{x_j\}) - f(x_S)\right) $$

where $\phi_j$ represents the contribution of feature $x_j$ to the model’s prediction, and $S$ is a subset of features excluding $x_j$. By using SHAP values, developers can provide transparency into how each feature affects the model’s decisions, enabling stakeholders to hold the system accountable for its outputs.

Finally, ensuring accountability in machine learning systems involves creating mechanisms that allow for the monitoring, auditing, and adjustment of models after deployment. Accountability frameworks should ensure that when a model produces unfair or harmful outcomes, there is a clear process for identifying the issue, addressing it, and preventing future occurrences. Rust’s system-level capabilities can be leveraged to build logging and auditing mechanisms into the machine learning pipeline, ensuring that all model decisions are traceable and that developers are alerted to any ethical concerns that arise during the model’s deployment.

In conclusion, ethics and fairness are fundamental to the responsible development of machine learning systems. By drawing from philosophical frameworks such as utilitarianism, deontology, and virtue ethics, developers can ensure that their models align with ethical principles and societal values. In Rust-based machine learning projects, these principles can be practically implemented through bias audits, transparency mechanisms, and accountability frameworks. By embedding these ethical considerations into the heart of the machine learning development process, developers can create systems that are not only technically robust but also ethically sound, ensuring that the benefits of machine learning are distributed fairly across society.

In practice, implementing ethical guidelines within Rust-based machine learning projects involves a multi-faceted approach. Rust, known for its performance and safety, provides a robust environment for developing machine learning applications while adhering to ethical principles. One effective strategy is to integrate ethical frameworks into the development lifecycle, ensuring that ethical considerations are not an afterthought but rather a core component of the design process. For example, developers can establish a set of ethical guidelines that are regularly revisited and refined throughout the project. This can include conducting bias audits on datasets, ensuring that training data is representative of the population, and implementing mechanisms to promote transparency and accountability in how models make decisions.

To illustrate this approach in a Rust-based machine learning project, consider the following sample code that demonstrates how to evaluate a model's fairness by assessing its performance across different demographic groups. In this example, we will create a simple function that checks for disparate impact, a common fairness metric, which quantifies whether a model's predictions disproportionately affect certain groups.

use std::collections::HashMap;

fn evaluate_fairness(predictions: Vec<(String, bool)>, demographics: Vec<(String, String)>) -> HashMap<String, f64> {

let mut group_counts: HashMap<String, (u32, u32)> = HashMap::new();

for (pred, demo) in predictions.iter().zip(demographics.iter()) {

let group = demo.1.clone();

let success = if pred.1 { 1 } else { 0 }; // Removed dereferencing here

let entry = group_counts.entry(group).or_insert((0, 0));

entry.0 += 1; // Total instances

entry.1 += success; // Successful predictions

}

let mut fairness_metrics: HashMap<String, f64> = HashMap::new();

for (group, (total, successes)) in group_counts {

let success_rate = successes as f64 / total as f64;

fairness_metrics.insert(group, success_rate);

}

fairness_metrics

}

fn main() {

let predictions = vec![

("user1".to_string(), true),

("user2".to_string(), false),

("user3".to_string(), true),

("user4".to_string(), false),

];

let demographics = vec![

("user1".to_string(), "GroupA".to_string()),

("user2".to_string(), "GroupB".to_string()),

("user3".to_string(), "GroupA".to_string()),

("user4".to_string(), "GroupB".to_string()),

];

let fairness_results = evaluate_fairness(predictions, demographics);

for (group, rate) in fairness_results {

println!("Success rate for {}: {:.2}%", group, rate * 100.0);

}

}

In this example, we define a function evaluate_fairness that calculates the success rate of predictions based on demographic data. The function takes a vector of predictions and corresponding demographic information, aggregates the results by group, and returns a map of success rates for each demographic group. This approach allows developers to assess the fairness of their model in a systematic manner, enabling them to identify and address any disparities in outcomes.

By embedding such ethical evaluations into the development process, Rust developers can take proactive steps to ensure that their machine learning systems are not only efficient and effective but also fair and just. This integration of ethical considerations into the design and implementation of machine learning projects serves as a crucial step toward fostering an AI landscape that prioritizes the well-being of all individuals, ultimately contributing to a more equitable society.

25.2. Bias in Machine Learning

Bias in machine learning represents a significant challenge that can substantially affect the outcomes, fairness, and generalizability of models. Understanding the various types of bias, their origins, and their broader implications is critical for machine learning practitioners who aim to develop equitable and effective systems. Bias in machine learning can be categorized into several distinct types, including sampling bias, confirmation bias, and algorithmic bias, each of which arises at different stages of the model development process. The presence of bias in models can lead to unfair treatment of certain groups, inaccurate predictions, and reduced generalization in real-world applications. Thus, identifying and mitigating bias is essential to building models that perform fairly and ethically across diverse populations.

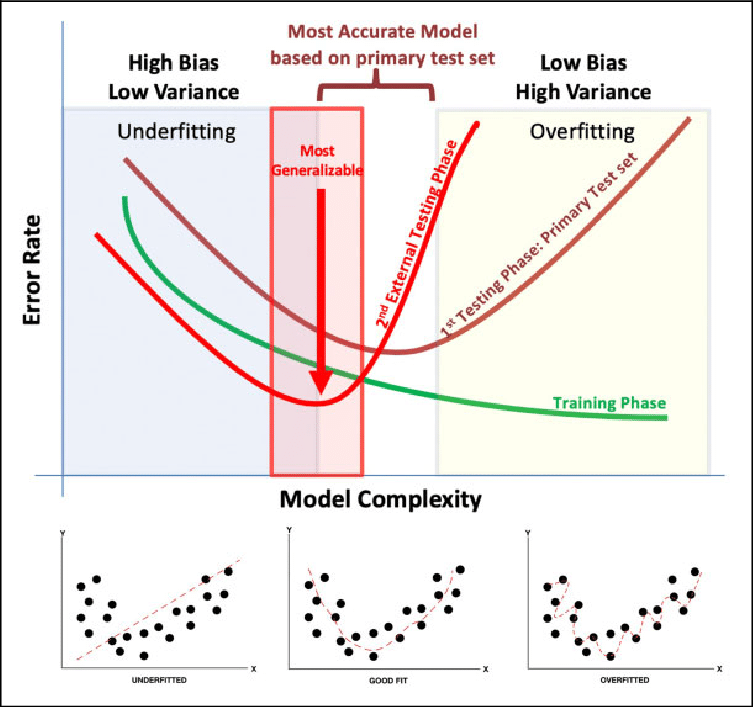

Figure 2: Identifying bias from Error rate and model complexity.

Sampling bias occurs when the data used to train the model does not accurately represent the underlying population for which the model is intended. Mathematically, let $D = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^n$ be a training dataset, where $x_i \in \mathbb{R}^d$ represents the input features and $y_i \in \mathbb{R}$ represents the target labels. If the data $D$ is sampled from a non-representative subset of the population, the learned model $f_{\theta}(x)$, parameterized by $\theta$, may overfit to the characteristics of the training data and fail to generalize to the broader population. Let $P_{\text{train}}(x, y)$ denote the distribution of the training data and $P_{\text{real}}(x, y)$ the distribution of the real-world population. If $P_{\text{train}}(x, y) \neq P_{\text{real}}(x, y)$, the model is at risk of making biased or inaccurate predictions. For instance, consider a facial recognition system trained predominantly on images from a specific demographic group. The model may achieve high accuracy on individuals from that group but perform poorly on individuals from underrepresented groups, thus failing to generalize due to the mismatch between the training and real-world distributions.

Confirmation bias, in the context of machine learning, refers to the tendency of practitioners to favor data or features that align with their pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses, potentially leading to biased models. This form of bias often manifests during the stages of data selection, feature engineering, or hypothesis testing. For example, if a practitioner believes that a specific set of features $\{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_k\}$ is more predictive of the target variable, they may unconsciously prioritize these features during the feature selection process while disregarding other important but less obvious features. Formally, let $\mathcal{F} = \{f_1, f_2, \dots, f_d\}$ represent the feature set available for training. In the presence of confirmation bias, the practitioner may restrict the model to a subset $\mathcal{F}' \subset \mathcal{F}$ based on preconceived notions, without fully exploring the predictive power of the entire feature space. This selective feature engineering can skew the model toward specific outcomes and reduce its ability to learn from the data in an unbiased manner.

Algorithmic bias arises from the design and optimization processes of machine learning algorithms themselves. This form of bias can occur when the algorithms make implicit assumptions about the data or when certain groups are underrepresented or misrepresented in the training set. Consider a classification model trained to minimize a loss function $\mathcal{L}(\theta)$, such as cross-entropy loss, over a dataset $D$. If certain demographic groups are not adequately represented in $D$, the model may optimize its parameters $\theta$ in a way that favors the majority group, leading to biased predictions. Formally, the objective function in a biased setting may take the form:

$$ \theta^* = \arg \min_{\theta} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \mathcal{L}(f_{\theta}(x_i), y_i) $$

where the loss $\mathcal{L}(f_{\theta}(x_i), y_i)$ is minimized over a dataset that does not adequately represent all demographic groups, causing the model to perform poorly on underrepresented groups. Algorithmic bias can also emerge from the structure of the model itself. For instance, if a decision tree model prioritizes certain features over others, it may inadvertently encode biases related to those features. Similarly, deep neural networks, which learn hierarchical representations of the data, may propagate biases present in the training set through multiple layers of abstraction, resulting in biased predictions.

The introduction of bias into machine learning models can occur at several stages, from data collection to preprocessing and algorithmic design. During data collection, if the samples are drawn from a biased or non-representative subset of the population, the resulting model will likely reflect these biases. For example, in a healthcare application, if a machine learning model is trained predominantly on data from a specific age group or geographic region, the model may not generalize well to patients from different age groups or regions. Formally, let $X = \{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\}$ be the set of input features collected during the data collection process. If the distribution of $X$ in the training data does not match the distribution of $X$ in the population, the learned model $f_{\theta}(x)$ will be biased toward the characteristics of the training data.

Bias can also be introduced during the preprocessing stage, where techniques such as normalization, feature selection, or dimensionality reduction are applied to the data. For instance, if certain features are disproportionately weighted or normalized in a way that favors specific groups, the model may learn to prioritize these groups over others. Let $\tilde{X} = \text{Preprocess}(X)$ represent the preprocessed feature set. If the preprocessing function $\text{Preprocess}(\cdot)$ introduces systematic bias by, for example, normalizing features in a way that amplifies differences between certain groups, the resulting model will reflect these biases in its predictions. Furthermore, algorithmic choices, such as the selection of loss functions, model architectures, or optimization methods, can reinforce existing biases in the data. For example, a loss function that disproportionately penalizes errors for certain classes may lead to biased outcomes for minority groups.

In conclusion, bias in machine learning is a multifaceted issue that can arise at various stages of the model development process, including data collection, preprocessing, and algorithm design. Different types of bias, such as sampling bias, confirmation bias, and algorithmic bias, can lead to unfair or inaccurate models that do not generalize well across diverse populations. Addressing bias requires a deep understanding of its sources and implications, as well as the implementation of strategies to mitigate its effects. By carefully designing data collection processes, applying rigorous preprocessing techniques, and incorporating fairness constraints into model training, machine learning practitioners can develop models that are both fair and effective across different demographic groups.

In practical terms, detecting bias in datasets is a crucial step in ensuring fairness in machine learning applications. Rust, being a systems programming language that emphasizes safety and concurrency, provides a robust environment for implementing bias detection strategies. Using Rust’s powerful data manipulation and statistical libraries, practitioners can analyze datasets to identify potential biases. For instance, one might use the ndarray crate to handle multi-dimensional arrays, which can facilitate the analysis of distributions across different demographic groups. Here’s an example of how one might analyze a dataset for bias:

use ndarray::Array2;

fn detect_bias(data: Array2<f64>, group_labels: Vec<i32>) -> f64 {

let mut group_means = vec![0.0; 2];

let mut group_counts = vec![0; 2];

for (i, &label) in group_labels.iter().enumerate() {

group_means[label as usize] += data.row(i).sum();

group_counts[label as usize] += 1;

}

for i in 0..group_means.len() {

group_means[i] /= group_counts[i] as f64;

}

let overall_mean = data.sum() / data.len() as f64;

let bias_score = group_means.iter().map(|&mean| (mean - overall_mean).abs()).sum();

bias_score

}

In this code, we define a function detect_bias that takes a 2D array representing the data and a vector of group labels. The function calculates the mean outcome for each group and compares it to the overall mean, resulting in a bias score. This score can help identify whether certain groups are systematically advantaged or disadvantaged by the model.

Once bias has been detected, it is essential to employ mitigation strategies to reduce its impact. Common techniques include re-sampling, re-weighting, and modifying algorithms. Re-sampling involves adjusting the dataset such that underrepresented groups are adequately represented, which can be achieved by duplicating instances of underrepresented classes or by generating synthetic samples using techniques such as SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique). Re-weighting assigns different weights to instances in the training set based on their group membership or importance, effectively altering the learning process to account for disparities. Modifying algorithms can involve tweaking the loss function to impose fairness constraints or implementing adversarial techniques that penalize biased predictions.

Here’s a simple implementation of re-weighting in Rust:

fn re_weight(data: &mut Array2<f64>, weights: Vec<f64>) {

for (i, mut row) in data.axis_iter_mut(ndarray::Axis(0)).enumerate() {

row.mapv_inplace(|x| x * weights[i]);

}

}

fn main() {

// Create example data

let mut data = Array2::<f64>::zeros((5, 3)); // 5 samples, 3 features each

let weights = vec![0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 1.0, 0.5]; // Weights assigned to instances

let group_labels = vec![0, 1, 0, 1, 0]; // Example group labels

// Re-weight data to address bias

re_weight(&mut data, weights);

println!("Re-weighted data: {:?}", data);

// Detect bias in the data

let bias_score = detect_bias(data, group_labels);

println!("Bias score: {}", bias_score);

}

In this example, the re_weight function accepts a mutable reference to a 2D array of data and a vector of weights. It scales each row of the data by the corresponding weight to adjust the model’s learning process, thus addressing potential biases present in the dataset.

In conclusion, understanding and addressing bias in machine learning is essential for developing fair and equitable models. By identifying different types of bias and their sources, practitioners can take concrete steps to mitigate their effects. Using Rust’s efficient data processing capabilities, one can implement techniques to detect and reduce bias, ultimately leading to more reliable and just machine learning applications. As the field continues to evolve, a commitment to ethical practices and fairness in model development will be paramount in shaping the future of machine learning.

25.3 Fairness Metrics and Their Application

In machine learning, fairness is not merely an abstract or philosophical concern; it is a vital element that directly affects the ethical deployment of models in real-world applications. As machine learning systems are increasingly being used to make consequential decisions in domains such as finance, healthcare, and criminal justice, it is crucial to evaluate the fairness of these models to ensure that their predictions do not perpetuate existing societal biases. Several fairness metrics have been developed to address different aspects of fairness, each providing a unique perspective on how to evaluate the performance of machine learning models across demographic groups. Key among these metrics are demographic parity, equalized odds, and predictive parity. These metrics offer formal ways to quantify fairness, allowing practitioners to identify and address biases that may arise from both the data and the model itself.

Demographic parity, also known as statistical parity, is a fairness metric that seeks to ensure that a machine learning model's positive predictions are distributed equally across different demographic groups. Formally, let $f_{\theta}$ represent a model’s prediction, where $x \in \mathbb{R}^d$ denotes the input features and $\theta \in \mathbb{R}^p$ represents the model parameters. Let $A$ denote a sensitive attribute, such as race or gender, with possible values $a_1, a_2, \dots, a_k$. Demographic parity requires that the probability of a positive prediction $f_{\theta}(x) = 1$ be equal across all groups:

$$ P(f_{\theta}(x) = 1 \mid A = a_i) = P(f_{\theta}(x) = 1 \mid A = a_j) \quad \forall i, j $$

This condition ensures that no demographic group receives disproportionately more or fewer positive predictions. For instance, in the context of a loan approval model, demographic parity would require that the proportion of approved loans is similar for individuals from different racial or gender groups. While this approach can promote equality in terms of outcomes, it does not consider the underlying distribution of the data. Consequently, enforcing demographic parity without considering merit or qualification can lead to suboptimal decisions, especially in cases where there are legitimate differences in the qualifications or characteristics of individuals in different demographic groups.

Equalized odds is another fairness metric that extends the notion of fairness by considering the model’s performance in terms of its error rates. Specifically, equalized odds requires that the true positive rate (TPR) and the false positive rate (FPR) be equal across different demographic groups. Let $y \in \{0, 1\}$ denote the true label, where $y = 1$ represents a positive outcome (e.g., loan approval or job selection), and $y = 0$ represents a negative outcome (e.g., loan denial or job rejection). Equalized odds can be expressed as:

$$ P(f_{\theta}(x) = 1 \mid A = a_i, y = 1) = P(f_{\theta}(x) = 1 \mid A = a_j, y = 1) \quad \forall i, j $$

and

$$ P(f_{\theta}(x) = 1 \mid A = a_i, y = 0) = P(f_{\theta}(x) = 1 \mid A = a_j, y = 0) \quad \forall i, j $$

This ensures that the model has equal true positive rates (TPR) and false positive rates (FPR) across all groups. For example, in a hiring algorithm, equalized odds would ensure that qualified candidates from different demographic backgrounds are equally likely to be selected (TPR), and unqualified candidates from different backgrounds are equally likely to be rejected (FPR). This metric is useful in contexts where fairness in terms of equal opportunity is essential. However, optimizing for equalized odds may require adjusting the decision thresholds for different groups, which can lead to trade-offs with overall model accuracy. In particular, achieving equalized odds may involve sacrificing some degree of predictive power in order to ensure that all groups are treated fairly in terms of error rates.

Predictive parity, in contrast, focuses on the calibration of the model’s predictions. Predictive parity requires that, for individuals who receive the same predicted probability of a positive outcome, the actual probability of that outcome occurring is the same across different demographic groups. Formally, let $\hat{p}(x) = P(y = 1 \mid x)$ represent the predicted probability of a positive outcome for input xxx. Predictive parity can be expressed as:

$$ P(y = 1 \mid \hat{p}(x) = p, A = a_i) = P(y = 1 \mid \hat{p}(x) = p, A = a_j) \quad \forall i, j $$

This ensures that the predicted probability of success is consistent across groups. For example, if two individuals from different demographic groups both receive a prediction of a 70% likelihood of success (e.g., for loan repayment or job performance), predictive parity requires that both individuals have an equal likelihood of achieving that outcome in reality. This metric is particularly valuable in applications where the reliability of the model’s predictions is critical, such as in financial lending or risk assessment. However, predictive parity does not account for differences in the underlying data distribution across groups, and in some cases, enforcing predictive parity can exacerbate existing biases in the data.

Each of these fairness metrics—demographic parity, equalized odds, and predictive parity—offers a different perspective on fairness, and their appropriateness depends on the context in which the machine learning model is being deployed. For example, in situations where equal outcomes across demographic groups are prioritized, demographic parity may be the most relevant metric. However, this may come at the cost of predictive accuracy, as the model may be forced to make decisions that do not reflect the actual merit of individuals. Conversely, focusing on equalized odds may help ensure that all demographic groups are treated fairly in terms of their true and false positive rates, but this may require adjusting decision thresholds, which can lead to reductions in the overall accuracy of the model. Predictive parity, while useful for ensuring consistency in predicted outcomes, may not always capture the full complexity of fairness, particularly when the underlying data is imbalanced or biased.

In practice, applying these fairness metrics in machine learning models requires a deep understanding of the trade-offs involved. For example, optimizing for demographic parity might involve reweighting the training data or introducing constraints during model training to ensure that positive predictions are equally distributed across demographic groups. Similarly, achieving equalized odds might require adjusting decision thresholds for different groups or incorporating fairness constraints into the model’s objective function. Rust, with its emphasis on performance and safety, provides an ideal platform for implementing fairness-aware machine learning models, allowing developers to build robust systems that account for fairness while maintaining computational efficiency.

In conclusion, fairness in machine learning is a multifaceted concept that requires careful consideration of the specific fairness metrics that are most relevant to the context of the model’s deployment. Demographic parity, equalized odds, and predictive parity each provide valuable frameworks for evaluating the fairness of a model’s predictions, but they also introduce trade-offs in terms of accuracy, opportunity, and reliability. By understanding these metrics and their implications, machine learning practitioners can develop models that are not only accurate but also fair and ethical in their treatment of diverse demographic groups.

Implementing fairness metrics in Rust can be achieved by leveraging the language's strong type system and performance capabilities. To illustrate this, let’s consider a simple Rust program that evaluates demographic parity for a binary classification model. We will assume we have a dataset containing demographic information and model predictions.

use std::collections::HashMap;

struct Prediction {

group: String,

predicted_positive: bool,

}

fn calculate_demographic_parity(predictions: Vec<Prediction>) -> HashMap<String, f64> {

let mut group_count: HashMap<String, usize> = HashMap::new();

let mut positive_count: HashMap<String, usize> = HashMap::new();

for pred in predictions {

*group_count.entry(pred.group.clone()).or_insert(0) += 1;

if pred.predicted_positive {

*positive_count.entry(pred.group).or_insert(0) += 1;

}

}

let mut demographic_parity: HashMap<String, f64> = HashMap::new();

for (group, count) in group_count {

let positive_rate = *positive_count.get(&group).unwrap_or(&0) as f64 / count as f64;

demographic_parity.insert(group, positive_rate);

}

demographic_parity

}

fn main() {

let predictions = vec![

Prediction { group: "A".to_string(), predicted_positive: true },

Prediction { group: "A".to_string(), predicted_positive: false },

Prediction { group: "B".to_string(), predicted_positive: true },

Prediction { group: "B".to_string(), predicted_positive: true },

];

let dp = calculate_demographic_parity(predictions);

println!("{:?}", dp);

}

In this example, we define a Prediction struct to hold the demographic group and the model's prediction. The calculate_demographic_parity function computes the positive prediction rates for each group, revealing potential disparities that warrant further examination. The output will inform us whether our model maintains demographic parity or if certain groups are disproportionately favored or disadvantaged.

As we evaluate model fairness, selecting appropriate metrics based on the application context is imperative. In a healthcare setting, equalized odds might be prioritized to ensure equitable access to treatments. In contrast, a credit scoring application might lean towards demographic parity to promote inclusive lending practices. Ultimately, the choice of fairness metrics should be guided by the ethical implications of the model's decisions, the values of stakeholders, and the potential societal impact of deploying such systems.

In conclusion, the application of fairness metrics in machine learning is not merely a technical endeavor but a profound ethical responsibility. Understanding the fundamental concepts of demographic parity, equalized odds, and predictive parity allows practitioners to navigate the complex trade-offs inherent in designing fair models. By implementing these metrics in Rust, we can create robust and efficient systems that not only excel in performance but also uphold the principles of fairness and equity in their predictions.

25.4 Transparency and Explainability in AI

In the realm of machine learning, particularly within the context of Rust, the concepts of transparency and explainability are paramount. As AI systems become increasingly prevalent in decision-making processes across various sectors, the necessity for users to understand and trust these systems grows ever more critical. Transparency refers to the clarity with which the operations of an algorithm can be understood, while explainability pertains to the ability of users to comprehend the rationale behind specific model predictions or decisions. These principles are essential not only for fostering user trust but also for ensuring accountability, particularly in high-stakes applications such as healthcare, finance, and criminal justice.

To achieve transparency and explainability in AI models, several techniques can be employed. One such technique is model simplification, which involves creating a more straightforward version of a complex model. This simplified model should retain the significant characteristics of the original while being easier for users to understand. Another technique is feature importance analysis, which helps identify which features are most influential in driving predictions. By understanding which variables are impacting outcomes, users can gain insights into the decision-making process of the model. Lastly, post-hoc explanations are crucial for elucidating the workings of models after they have been trained. These explanations can take various forms, such as local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) or SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), which provide users with confidence that the model behaves as expected.

In Rust, implementing transparency and explainability features can be achieved through the use of various libraries and tools designed for machine learning and data analysis. One of the popular libraries for machine learning in Rust is linfa, which provides a comprehensive suite of algorithms that can be easily utilized for building interpretable models. For example, a simple linear regression model can be constructed using linfa, allowing us to analyze the coefficients associated with each feature to understand their importance.

Here is a basic example of how to implement a linear regression model in Rust using the linfa library, followed by an analysis of feature importance:

use linfa::prelude::*;

use linfa_linear::LinearRegression;

use ndarray::Array1; // Import Array1 for 1D array (vector) usage

fn main() {

// Sample dataset: 3 features and 5 samples

let x = ndarray::Array2::from_shape_vec((5, 3), vec![

1.0, 2.0, 3.0,

1.5, 3.5, 4.5,

2.0, 4.0, 6.0,

2.5, 5.5, 7.5,

3.0, 6.0, 9.0,

]).unwrap();

// `y` should be a 1D array (vector)

let y = Array1::from_vec(vec![

1.0,

2.0,

3.0,

4.0,

5.0,

]);

// Create a dataset

let dataset = Dataset::new(x, y);

// Train a linear regression model

let model = LinearRegression::default().fit(&dataset).unwrap();

// Retrieve the intercept and coefficients from the fitted model

let intercept = model.intercept();

let coefficients = model.params();

println!("Model Intercept: {:?}", intercept);

println!("Model Coefficients: {:?}", coefficients);

// Predicting using the model

let sample = ndarray::Array2::from_shape_vec((1, 3), vec![2.0, 4.0, 6.0]).unwrap();

let prediction = model.predict(&sample);

println!("Predicted value: {:?}", prediction);

}

In this example, we create a simple linear regression model using the linfa library. After training the model, we extract the coefficients, which provide insights into the contribution of each feature to the prediction. This straightforward approach allows users to easily interpret how changes in input features can affect the model's output.

Furthermore, we can enhance the model's explainability by implementing post-hoc explanation techniques. For instance, we can employ the LIME methodology to explain individual predictions. While Rust may not have a direct implementation of LIME, we can create a simplified version to illustrate the concept. This involves perturbing the input features and observing the changes in predictions, allowing us to estimate the local contribution of each feature to a specific prediction. Below is a conceptual illustration of how this could be structured in Rust, although the actual implementation may require additional dependencies or libraries for statistical computations.

use linfa::prelude::*; // Import prelude which includes all necessary traits like Predict

use linfa_linear::{LinearRegression, FittedLinearRegression}; // Import LinearRegression and FittedLinearRegression

use ndarray::{Array2, Array1, s}; // Use Array2 for inputs, Array1 for outputs, and slicing

use rand::prelude::*; // For random number generation

use rand_distr::Normal; // For Gaussian noise

/// Performs a simplified LIME-like explanation by perturbing input features and analyzing predictions.

///

/// # Arguments

///

/// * `model` - A reference to the fitted linear regression model.

/// * `input` - A reference to the input sample (2D array with a single row).

/// * `num_samples` - The number of perturbations to generate.

///

/// # Returns

///

/// A vector containing the feature importance scores.

fn lime_explain(model: &FittedLinearRegression<f64>, input: &Array2<f64>, num_samples: usize) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut perturbations = Vec::with_capacity(num_samples);

let mut predictions = Vec::with_capacity(num_samples);

// Initialize random number generator and Gaussian noise distribution

let mut rng = thread_rng();

let noise_distribution = Normal::new(0.0, 0.1).unwrap(); // Mean 0, Std Dev 0.1

// Generate perturbations and collect predictions

for _ in 0..num_samples {

let perturbed_sample = perturb(input, &mut rng, &noise_distribution);

let dummy_output: Array1<f64> = Array1::zeros(1); // Dummy target with explicit type annotation

let dataset = DatasetBase::new(perturbed_sample.clone(), dummy_output);

let prediction_dataset = model.predict(&dataset); // Use the `predict` method

// **Fix Applied Here:**

// Bind the temporary `as_targets()` to a variable to extend its lifetime

let targets = prediction_dataset.as_targets();

let prediction = targets.get(0).unwrap(); // Extract the prediction

perturbations.push(perturbed_sample);

predictions.push(*prediction);

}

// Analyze the perturbations and predictions to derive feature importance

let feature_importance = analyze_importance(&perturbations, &predictions);

feature_importance

}

/// Adds Gaussian noise to the input features to create a perturbed sample.

///

/// # Arguments

///

/// * `input` - A reference to the input sample.

/// * `rng` - A mutable reference to the random number generator.

/// * `noise_dist` - A reference to the Gaussian noise distribution.

///

/// # Returns

///

/// A new `Array2<f64>` with perturbed features.

fn perturb(input: &Array2<f64>, rng: &mut impl Rng, noise_dist: &Normal<f64>) -> Array2<f64> {

let mut perturbed = input.clone();

for mut row in perturbed.rows_mut() {

for val in row.iter_mut() {

*val += rng.sample(noise_dist);

}

}

perturbed

}

/// Analyzes the covariance between each feature and the model's predictions to determine feature importance.

///

/// # Arguments

///

/// * `perturbations` - A slice of perturbed input samples.

/// * `predictions` - A slice of corresponding predictions.

///

/// # Returns

///

/// A vector of feature importance scores.

fn analyze_importance(perturbations: &[Array2<f64>], predictions: &[f64]) -> Vec<f64> {

// Compute the mean of predictions

let mean_pred: f64 = predictions.iter().sum::<f64>() / predictions.len() as f64;

// Determine the number of features from the first perturbation

let num_features = perturbations[0].ncols();

let mut importance = Vec::with_capacity(num_features);

// Compute covariance between each feature and predictions

for feature_idx in 0..num_features {

let feature_values: Vec<f64> = perturbations.iter()

.map(|perturb| perturb[[0, feature_idx]]) // Assuming single sample per perturbation

.collect();

let mean_feature: f64 = feature_values.iter().sum::<f64>() / feature_values.len() as f64;

let covariance: f64 = feature_values.iter()

.zip(predictions.iter())

.map(|(&xi, &yi)| (xi - mean_feature) * (yi - mean_pred))

.sum::<f64>() / (feature_values.len() as f64 - 1.0);

importance.push(covariance);

}

importance

}

fn main() {

// Indicate the start of the LIME explanation process

println!("LIME explanation process in progress!");

// Sample dataset: 3 features and 5 samples

let x = Array2::from_shape_vec((5, 3), vec![

1.0, 2.0, 3.0,

1.5, 3.5, 4.5,

2.0, 4.0, 6.0,

2.5, 5.5, 7.5,

3.0, 6.0, 9.0,

]).unwrap();

// Corresponding target values

let y = Array1::from_vec(vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0]);

// Create a dataset from features and targets

let dataset = DatasetBase::new(x, y);

// Train a linear regression model

let fitted_model: FittedLinearRegression<f64> = LinearRegression::default().fit(&dataset).unwrap();

// Select a single sample for explanation (the first sample)

let sample = dataset.records().slice(s![0..1, ..]).to_owned();

// Perform LIME-like explanation with 10 perturbations

let feature_importance = lime_explain(&fitted_model, &sample, 10);

// Display the feature importance scores

println!("Feature importance: {:?}", feature_importance);

}

In summary, the integration of transparency and explainability into AI models developed in Rust is not just a technical necessity but also a moral obligation in the age of AI. By employing techniques such as model simplification, feature importance analysis, and post-hoc explanations, developers can create more interpretable models that foster user trust and understanding. The linfa library serves as a valuable tool for implementing these concepts, allowing users to build robust machine learning models while ensuring that their operations are transparent and their decisions are explainable. As we continue to advance in the field of machine learning, prioritizing these aspects will be crucial in guiding ethical AI development and deployment.

25.5 Accountability and Responsibility in AI Systems

In the domain of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), accountability plays a foundational role in ensuring the ethical deployment of these technologies. As AI systems increasingly influence decisions in critical areas such as healthcare, finance, and criminal justice, it is essential that these decisions can be traced back to responsible individuals or organizations. Accountability ensures that there is transparency in the decision-making processes of AI systems, enabling stakeholders to identify and address issues such as errors, biases, and misjudgments. More broadly, accountability fosters public trust by providing assurances that AI systems are being used in a responsible and ethical manner.

The concept of accountability in AI involves establishing a clear and traceable linkage between the decisions made by machine learning models and the humans or organizations responsible for those decisions. This traceability is crucial for ensuring that AI systems operate in a manner that aligns with societal values and ethical standards. Formally, let $f_{\theta}(x)$ represent a machine learning model with parameters $\theta$, where $x \in \mathbb{R}^d$ denotes the input features. The model’s decision $y = f_{\theta}(x)$ should be linked to a documented process that explains how $\theta$ was learned, how $x$ was processed, and who is accountable for the outcomes. Such traceability requires mechanisms that document every stage of the decision-making process, from data collection and preprocessing to model training and deployment. Without this level of documentation, it becomes difficult to hold any party accountable for the actions or consequences of the AI system.

A core mechanism for establishing accountability in AI systems is the implementation of audit trails. An audit trail is a detailed record of all actions and decisions made by the system, including the inputs provided to the model, the outputs generated, and any modifications made to the model over time. Mathematically, let $D = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^n$ represent the training data used to learn the model parameters $\theta$. An audit trail would document not only the training data $D$, but also the loss function $\mathcal{L}(\theta, D)$, the optimization process used to minimize the loss function, and any subsequent changes to $\theta$ based on updated data or model adjustments. Formally, this can be expressed as:

$$\theta^{(t+1)} = \theta^{(t)} - \eta \nabla_{\theta} \mathcal{L}(\theta^{(t)}, D)$$

where $\eta$ represents the learning rate, and ttt is the iteration number. The audit trail would record each update to $\theta$, providing a clear log of how the model evolved over time. Such documentation is invaluable for diagnosing issues, as it allows stakeholders to trace the source of a problem back to specific inputs, updates, or decisions made during the training process. Moreover, if the model exhibits biased behavior or incorrect predictions, the audit trail can be used to hold relevant parties accountable for the design, data, or decisions that contributed to these outcomes.

Version control is another critical component of accountability in AI. Machine learning models are often subject to continuous updates as new data becomes available or as improvements are made to the model architecture. Version control systems provide a formal mechanism for tracking changes to the model over time, ensuring that each version of the model is properly documented and can be audited if necessary. Let $\theta^{(t)}$ represent the model parameters at iteration $t$. In a version-controlled system, each update to $\theta^{(t)}$ would be saved as a separate version, with metadata documenting the reason for the change, the individual responsible, and the effects of the update on the model's performance. This enables rollback to previous versions if new updates introduce errors or degrade performance. Mathematically, the state of the model at each version can be represented as a function of the data and the update rule:

$$ \theta^{(t+1)} = f(\theta^{(t)}, \nabla_{\theta} \mathcal{L}, D^{(t)}) $$

where $D^{(t)}$ represents the data at iteration $t$, and $f$ represents the update function. By maintaining a record of each $\theta^{(t)}$, version control systems provide a clear history of the model’s development, ensuring that changes are accountable and reversible.

In addition to audit trails and version control, governance frameworks are essential for ensuring accountability in the development and deployment of AI systems. Governance frameworks establish the policies, procedures, and standards that guide the responsible use of AI, ensuring that decisions made by AI systems comply with ethical guidelines and legal regulations. A governance framework typically defines roles and responsibilities within an organization, specifying who is accountable for different aspects of the AI system’s lifecycle, from design and development to deployment and monitoring. Let $G$ represent a governance framework, where $G = \{P, R, S\}$ consists of policies $P$, roles $R$, and standards $S$. Each element of the framework contributes to a structured approach to accountability, ensuring that:

$$ R(\text{developer}) \rightarrow \text{Responsible for model design and training} \quad $$

$$ R(\text{data scientist}) \rightarrow \text{Responsible for data selection and preprocessing} $$

By defining these roles and their associated responsibilities, governance frameworks provide clarity about who is accountable for the ethical and technical integrity of AI systems. Additionally, governance frameworks help ensure compliance with external regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe, which mandates that organizations using AI systems be able to explain and justify the decisions made by their models. Failure to adhere to these regulations can result in legal liabilities, making governance frameworks not only an ethical imperative but also a legal necessity.

In conclusion, accountability in AI systems is a critical aspect of ensuring ethical and responsible deployment. By implementing mechanisms such as audit trails, version control, and governance frameworks, organizations can create transparent, traceable, and accountable AI systems. These mechanisms enable stakeholders to understand and evaluate the decision-making processes of AI models, ensuring that the individuals and organizations responsible for those decisions can be held accountable. Rust, with its emphasis on system-level control and safety, provides an ideal platform for developing AI systems that integrate these accountability mechanisms, ensuring that the development and deployment of AI models align with both ethical standards and legal requirements.

In practical terms, implementing accountability features in Rust-based machine learning systems involves several key strategies. One of the primary approaches is logging, where a robust logging system can be integrated into the Rust application to capture critical events, including model predictions, input data, and user interactions. Rust's powerful standard library provides excellent support for logging through crates such as log and env_logger. For instance, you can set up logging in your Rust application as follows:

// Import necessary crates

use log::{info, error}; // For logging

use env_logger; // For initializing the logger

fn main() {

// Initialize the logger

env_logger::init();

// Log an informational message

info!("Starting the machine learning model...");

// Mock input data

let input_data = vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0]; // Example input data

// Simulate model prediction

let result = model_predict(&input_data);

if let Err(e) = result {

error!("Model prediction failed: {}", e);

} else {

info!("Model prediction succeeded: {:?}", result);

}

}

// Mock function to simulate a model prediction

fn model_predict(input_data: &Vec<f64>) -> Result<f64, &'static str> {

if input_data.is_empty() {

return Err("Input data is empty");

}

// Mock prediction logic (in a real case, replace this with actual model logic)

let prediction: f64 = input_data.iter().sum(); // Summing up the input as a mock prediction

Ok(prediction)

}

Here, the log and env_logger crates are utilized to document events occurring within the application. This logging framework can be further extended to include more granular details about the model's behavior, such as input features and the rationale behind specific predictions.

Another practical aspect of accountability is model versioning. In Rust, you can implement a simple versioning mechanism that tracks changes to your model parameters and architecture. By maintaining a version history, you can ensure that each deployment is associated with a specific version of the model, allowing for traceability. Below is an illustrative example of how you might implement a model versioning system:

use std::time::{SystemTime, UNIX_EPOCH};

struct ModelVersion {

version: String,

parameters: Vec<f64>,

created_at: SystemTime,

}

struct ModelRegistry {

versions: Vec<ModelVersion>,

}

impl ModelRegistry {

fn new() -> Self {

ModelRegistry {

versions: Vec::new(),

}

}

fn add_version(&mut self, version: String, parameters: Vec<f64>) {

let new_version = ModelVersion {

version,

parameters,

created_at: SystemTime::now(),

};

self.versions.push(new_version);

}

fn get_latest_version(&self) -> Option<&ModelVersion> {

self.versions.last()

}

}

fn main() {

let mut registry = ModelRegistry::new();

registry.add_version("1.0.0".to_string(), vec![0.1, 0.2, 0.3]);

if let Some(latest) = registry.get_latest_version() {

println!("Latest model version: {}", latest.version);

println!("Parameters: {:?}", latest.parameters);

let since_epoch = latest.created_at.duration_since(UNIX_EPOCH)

.expect("Time went backwards");

println!("Created at: {} seconds since UNIX epoch", since_epoch.as_secs());

}

}

In this example, the ModelRegistry struct maintains a collection of ModelVersion instances, each capturing the parameters and timestamp of a specific iteration of the model. By leveraging this registry, organizations can ensure that they can always reference the exact model that produced a given prediction, thereby enhancing accountability.

Furthermore, traceability mechanisms can be implemented to connect input data, model versions, and predictions. This can be achieved through unique identifiers assigned to each prediction, which are then logged alongside the input data and the corresponding model version. Such traceability not only aids in debugging but also helps in understanding the impact of specific data inputs on model outcomes.

In conclusion, accountability and responsibility in AI systems are indispensable for fostering trust and ensuring ethical practices in the deployment of machine learning technologies. By integrating mechanisms such as audit trails, version control, and robust logging systems into Rust-based machine learning applications, developers can create an environment where accountability is prioritized, and stakeholders can be held responsible for the outcomes generated by their models. As the landscape of AI continues to evolve, the commitment to accountability will be crucial in addressing the complexities and challenges that lie ahead.

25.6. Privacy Considerations in Machine Learning

In the domain of machine learning, safeguarding individual privacy is of critical importance, particularly in sensitive sectors like healthcare and finance where the improper use of personal data can result in significant harm. As AI systems become increasingly reliant on vast datasets to enhance their performance and make predictions, the ethical implications surrounding data collection, storage, and processing must be rigorously addressed. Privacy breaches not only lead to personal and financial harm but also erode public trust in AI technologies and can result in severe legal consequences. Therefore, protecting privacy while harnessing the potential of data is an essential challenge for machine learning practitioners.

To address this challenge, several robust privacy-preserving techniques have been developed. Among these, differential privacy, federated learning, and encryption stand out as critical approaches to ensuring that personal information remains confidential while still enabling the development of high-performing machine learning models. Each of these techniques employs different mathematical frameworks to achieve privacy, but all share the common goal of limiting the exposure of individual data.

Differential privacy offers a formal mathematical guarantee that the output of a machine learning model does not reveal too much information about any individual data point in the dataset. Formally, differential privacy is defined as follows: Let $M$ be a randomized algorithm that takes as input a dataset $D$ and produces an output $M(D)$. The algorithm $M$ satisfies $\epsilon$-differential privacy if, for any two neighboring datasets $D$ and $D'$ that differ by only one data point, and for any subset of possible outputs $S$, the following inequality holds:

$$ P(M(D) \in S) \leq e^{\epsilon} P(M(D') \in S) $$

Here, $\epsilon$ is the privacy budget, a parameter that controls the level of privacy provided by the algorithm. A smaller value of $\epsilon$ provides stronger privacy guarantees, ensuring that the inclusion or exclusion of a single data point does not significantly change the output of the algorithm. Differential privacy can be implemented in machine learning by adding noise to the model’s training process, either by perturbing the data itself or by adding noise to the gradients during training. Let $\nabla_{\theta} \mathcal{L}(D)$ represent the gradient of the loss function with respect to the model parameters θ\\thetaθ, computed over the dataset $D$. In the differentially private version, the gradient is perturbed by adding noise sampled from a distribution (e.g., Gaussian or Laplace) to each gradient update:

$$ \hat{\nabla}_{\theta} \mathcal{L}(D) = \nabla_{\theta} \mathcal{L}(D) + \eta $$

where $\eta$ represents the noise drawn from a distribution that satisfies the desired level of differential privacy. By ensuring that individual contributions to the model are obscured, differential privacy mitigates the risk of reverse-engineering sensitive information from the model’s output, making it an essential technique in privacy-sensitive applications such as healthcare.

Federated learning is another prominent technique that enhances privacy by decentralizing the model training process. Instead of gathering data in a central location, federated learning allows models to be trained directly on the devices where the data is generated (e.g., smartphones, IoT sensors). Let $f_{\theta}$ represent a machine learning model with parameters $\theta$, trained on input data $x$. In a federated learning setting, each device $i \in \mathcal{C}$, where $\mathcal{C}$ represents the set of devices, holds its own local dataset $D_i = \{(x_{ij}, y_{ij})\}_{j=1}^{n_i}$. The model is trained on each local dataset, and the local updates θi\\theta_iθi are sent to a central server, which aggregates these updates to produce a global model:

$$ \theta_{\text{global}} = \frac{1}{k} \sum_{i=1}^k \theta_i $$

where $k$ is the number of participating devices. This aggregation process ensures that the local data $D_i$ never leaves the individual devices, significantly reducing the risk of privacy breaches. Federated learning is particularly useful in scenarios where data is both sensitive and geographically distributed, such as in healthcare systems where medical data is stored across multiple hospitals or clinics. By keeping the data decentralized, federated learning minimizes the potential for data exposure while still enabling the training of robust machine learning models.

Encryption techniques also play a vital role in enhancing the security and privacy of machine learning models. Encryption ensures that data is encoded in such a way that only authorized parties can access it, protecting sensitive information from unauthorized users. One powerful approach to preserving privacy in machine learning is the use of homomorphic encryption, which allows computations to be performed directly on encrypted data without needing to decrypt it first. Let $E(x)$ denote the encryption of data $x$, and let $f_{\theta}(x)$ represent the model’s prediction for input $x$. Homomorphic encryption ensures that:

$$ E(f_{\theta}(x)) = f_{\theta}(E(x)) $$

This property allows machine learning models to be trained and evaluated on encrypted data, ensuring that sensitive information remains secure even during computation. For example, in a healthcare application, homomorphic encryption would allow a machine learning model to be trained on encrypted medical records without ever exposing the raw data to the server or other users. Although homomorphic encryption is computationally expensive, it provides a strong guarantee of privacy, making it an attractive option for applications where data security is paramount.

In conclusion, protecting privacy in machine learning is an essential consideration, particularly in domains where sensitive personal information is at stake. Differential privacy provides a mathematical framework for ensuring that individual data points do not overly influence the model’s output, while federated learning decentralizes the training process to keep data localized on the devices where it is generated. Encryption, particularly homomorphic encryption, further enhances privacy by allowing computations to be performed on encrypted data. Each of these techniques plays a critical role in addressing the privacy challenges associated with machine learning, and their thoughtful integration into machine learning pipelines ensures that the power of AI can be harnessed without compromising the privacy and security of individuals.

Implementing these privacy-preserving techniques in Rust can be a robust endeavor, as Rust’s focus on safety and concurrency aligns well with the demands of handling sensitive information. For instance, implementing differential privacy involves perturbing the data or the model's outputs. Below is a basic conceptual implementation of differential privacy in Rust, where we add Laplace noise to a model's predictions to obscure the effect of any single individual's data.

use rand::Rng;

fn laplace_noise(scale: f64) -> f64 {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let u: f64 = rng.gen_range(-0.5..0.5); // Uniform distribution from -0.5 to 0.5

let noise = -scale * u.signum() * (1.0 - 2.0 * u.abs()).ln(); // Correct Laplace noise generation

noise

}

fn apply_differential_privacy(original_value: f64, epsilon: f64) -> f64 {

let scale = 1.0 / epsilon; // Scale parameter for Laplace noise

original_value + laplace_noise(scale) // Add noise to the original value

}

fn main() {

let original_prediction = 0.85; // Example model prediction

let epsilon = 0.1; // Privacy parameter

let private_prediction = apply_differential_privacy(original_prediction, epsilon);

println!("Private Prediction: {}", private_prediction);

}

In this example, we introduce a function to generate Laplace noise based on a given scale, which is inversely proportional to the privacy parameter epsilon. The function apply_differential_privacy takes an original value—such as a model's prediction—and adds noise to ensure that the output does not reveal too much about any individual data point.

Furthermore, federated learning can also be implemented using Rust, although it requires a more complex setup involving communication between client devices and a central server. The Rust programming language provides excellent concurrency features that make it suitable for building such distributed systems. In a federated learning setup, the model is trained on local data, and only the updated model parameters are sent to the server. Below is a simplified conceptual code snippet that outlines how one might structure a federated learning update cycle in Rust.

use std::collections::HashMap;

struct Model {

parameters: HashMap<String, f64>, // Model parameters

}

impl Model {

fn update(&mut self, updates: &HashMap<String, f64>, weight: f64) {

for (key, value) in updates.iter() {

let current = self.parameters.entry(key.clone()).or_insert(0.0);

*current += weight * value; // Update the parameters with local updates

}

}

}

fn main() {

let mut global_model = Model {

parameters: HashMap::new(),

};

// Simulated local updates from client devices

let local_updates1 = HashMap::from([("weight1".to_string(), 0.1)]);

let local_updates2 = HashMap::from([("weight1".to_string(), 0.3)]);

// Update global model with local updates

global_model.update(&local_updates1, 0.5);

global_model.update(&local_updates2, 0.5);

println!("Updated Global Model: {:?}", global_model.parameters);

}

In this code, we define a Model struct that holds the model parameters. The update function allows for the aggregation of local updates, weighted appropriately before being applied to the global model, simulating a federated learning process.

Lastly, ensuring data protection throughout the AI lifecycle is critical. This encompasses the entire pipeline, from data collection and preprocessing to model training, evaluation, and deployment. Employing encryption methods such as AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) can help secure data at rest and in transit. Rust's aes crate provides a way to implement AES encryption easily. Below is a simple illustration of how one might encrypt data before storing it or sending it over a network.

extern crate aes;

extern crate block_modes;

extern crate generic_array;

use aes::Aes256;

use aes::cipher::{NewBlockCipher}; // Import only the necessary trait

use block_modes::{BlockMode, Cbc};

use block_modes::block_padding::Pkcs7;

use generic_array::GenericArray;

type Aes256Cbc = Cbc<Aes256, Pkcs7>;

fn encrypt(data: &[u8], key: &[u8], iv: &[u8]) -> Vec<u8> {

let key = GenericArray::from_slice(key); // Convert key to GenericArray

let iv = GenericArray::from_slice(iv); // Convert iv to GenericArray

let cipher = Aes256Cbc::new(Aes256::new(key), iv); // Create cipher with correct types

cipher.encrypt_vec(data)

}

fn main() {

let key = b"an example very very secret key."; // 32-byte key

let iv = b"unique nonce1234"; // 16-byte IV

let data = b"Sensitive information";

let encrypted_data = encrypt(data, key, iv);

println!("Encrypted Data: {:?}", encrypted_data);

}

In this final example, we utilize the aes and block_modes crates to encrypt sensitive information using AES in CBC mode. This ensures that the data remains confidential, even if intercepted.

In conclusion, as machine learning continues to evolve and permeate sensitive domains, the ethical considerations surrounding privacy must remain at the forefront of development. By integrating techniques such as differential privacy, federated learning, and encryption into our machine learning applications in Rust, we can strive to build systems that not only harness the power of data but also prioritize the protection of individual privacy. The responsibility lies with developers and practitioners to remain vigilant and ethical in their approach, ensuring that technology serves humanity with integrity and respect for personal data.

25.7 Ethical Implications of AI in Society

As artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) systems become increasingly integrated into various sectors of society, it is essential to recognize that their development is not purely a technical pursuit, but a deeply societal one. The ethical implications of AI, including job displacement, enhanced surveillance capabilities, and the potential for misuse, necessitate a thorough examination of the broader impacts by developers, policymakers, and other stakeholders. This integration raises significant concerns regarding not only the technological capabilities of AI but also the responsibility of those involved in its creation to mitigate its potential adverse societal consequences. The responsibility borne by developers goes beyond the technical aspects of code and algorithms; it includes an ethical obligation to consider the far-reaching effects of their systems on individuals, communities, and society at large.

One of the most pressing concerns regarding the societal implications of AI is job displacement. As AI systems become more capable of performing tasks that were traditionally the domain of human workers, there is a growing risk that automation will lead to significant disruptions in the workforce. For instance, in sectors such as manufacturing, logistics, and retail, AI-powered robots and machine learning algorithms are increasingly taking over tasks that were once labor-intensive. Mathematically, let $T$ represent the set of tasks performed in a given industry, where each task $t_i \in T$ has an associated probability $P(A_t)$ of being automated by AI. The expected impact on the workforce can be modeled as a function of the total number of tasks displaced by automation, $D(T)$, which is given by:

$$ D(T) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} P(A_t) \cdot L(t_i) $$

where $L(t_i)$ represents the number of workers involved in task $t_i$. As $P(A_t)$ increases, the displacement $D(T)$ grows, leading to potentially large-scale unemployment or shifts in job roles. While automation may increase efficiency and reduce costs, it is critical for developers and policymakers to account for these labor shifts. One strategy to mitigate the negative effects of automation is to prioritize job retraining and upskilling, enabling workers to transition into new roles that are less vulnerable to automation. This requires a concerted effort from both the developers creating AI systems and the organizations deploying them. Rust’s performance and system-level control make it an excellent tool for developing efficient AI systems, and these systems can be designed with a focus on augmenting, rather than replacing, human labor through collaborative AI models that enhance human productivity rather than displacing workers.

Another critical ethical concern is the use of AI in surveillance systems, which raises important questions about privacy and individual freedoms. Machine learning algorithms, especially those applied to facial recognition and other biometric identification techniques, have the potential to greatly enhance surveillance capabilities. Mathematically, let $F(x)$ represent a facial recognition model that maps input features $x$ (e.g., facial landmarks, pixel intensities) to a predicted identity $y$. While such systems can be highly accurate in security and law enforcement applications, they pose significant risks if deployed without proper safeguards. For instance, facial recognition systems may be used for mass surveillance, infringing on citizens' privacy and potentially leading to abuses in authoritarian regimes. Moreover, these systems may exhibit biases, particularly when the training data is skewed toward certain demographic groups, leading to disproportionately high error rates for underrepresented populations. Formally, let $\mathcal{L}(f_\theta(x), y)$ represent the loss function used to optimize the model. If the data distribution $P(X)$ is imbalanced across demographic groups, the model may minimize the loss for the majority group while performing poorly on the minority group, exacerbating societal inequities. Developers using Rust can implement privacy-preserving algorithms, such as differential privacy, to ensure that the data used in these models remains anonymous and secure. By embedding privacy as a core principle in the design and implementation of these systems, developers can mitigate the risks of AI-enhanced surveillance.

The ethical deployment of AI requires more than just technical solutions; it demands an in-depth understanding of the contexts in which these technologies are used. For example, in healthcare, machine learning models can significantly improve diagnostic accuracy and treatment outcomes, but they must be designed to ensure fairness and avoid biases that could lead to unequal treatment of patients from different demographic backgrounds. Let $D = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^n$ represent a dataset where $x_i \in \mathbb{R}^d$ are the input features (e.g., patient health data) and $y_i \in \{0, 1\}$ is the binary outcome (e.g., disease diagnosis). A fairness-aware model should ensure that the probability of a positive outcome $P(y = 1 \mid x)$ is independent of sensitive attributes such as race or gender, thus avoiding biased outcomes. Formally, this can be expressed as:

$$ P(f_{\theta}(x) = 1 \mid A = a) = P(f_{\theta}(x) = 1 \mid A = b) \quad \forall a, b \in A $$

where $A$ is the set of sensitive attributes. Rust, with its emphasis on memory safety and concurrency, provides an ideal platform for developing healthcare applications that must be both performant and reliable. Developers can leverage Rust’s features to build systems that are not only efficient but also fair, ensuring that the benefits of AI technologies are distributed equitably across different groups in society.

In conclusion, the integration of AI and machine learning technologies into various domains comes with profound ethical responsibilities that extend beyond the technical design of these systems. Developers must account for the societal impacts of their creations, including the potential for job displacement, privacy violations, and misuse in surveillance. By leveraging tools like Rust, developers can design AI systems that are efficient, privacy-preserving, and fair. Furthermore, collaboration with stakeholders across different industries is essential to fully understand the ethical implications of AI and to ensure that these technologies are used responsibly and for the benefit of all.

In practice, incorporating ethical considerations into AI development involves a holistic approach throughout the entire lifecycle of the AI system, from conception to deployment and beyond. Developers should start by conducting thorough impact assessments to identify potential ethical issues and societal impacts. This could involve simulations or analysis using Rust libraries such as ndarray for numerical computations to model different scenarios where AI systems might be applied, evaluating both positive and negative outcomes.

Furthermore, Rust's strong type system and memory safety features can help in creating transparent and interpretable AI models. By utilizing libraries such as tch-rs, which provides bindings to the PyTorch framework, developers can focus on building neural networks that not only perform well but are also explainable. This transparency is crucial for fostering trust and accountability, as stakeholders need to understand how decisions made by AI systems can affect their lives.