Chapter 26

Quantum Machine Learning

"The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science." — Albert Einstein

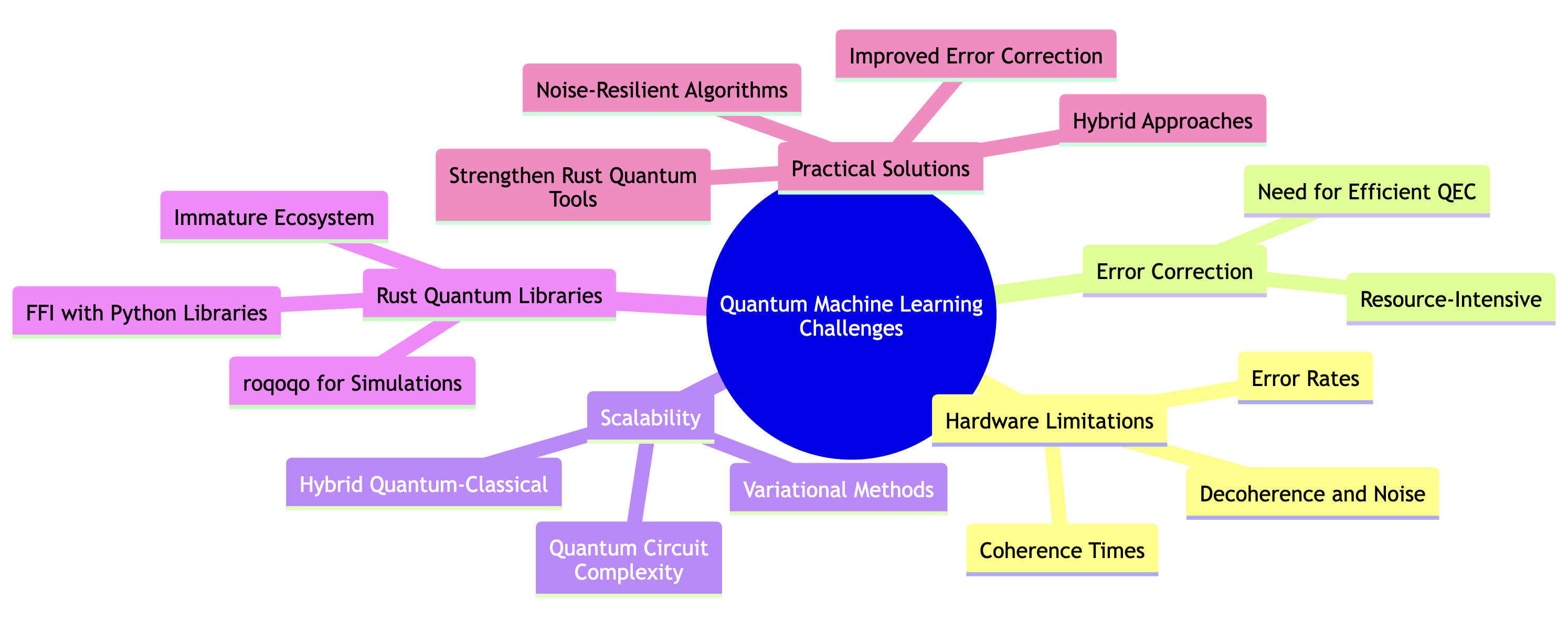

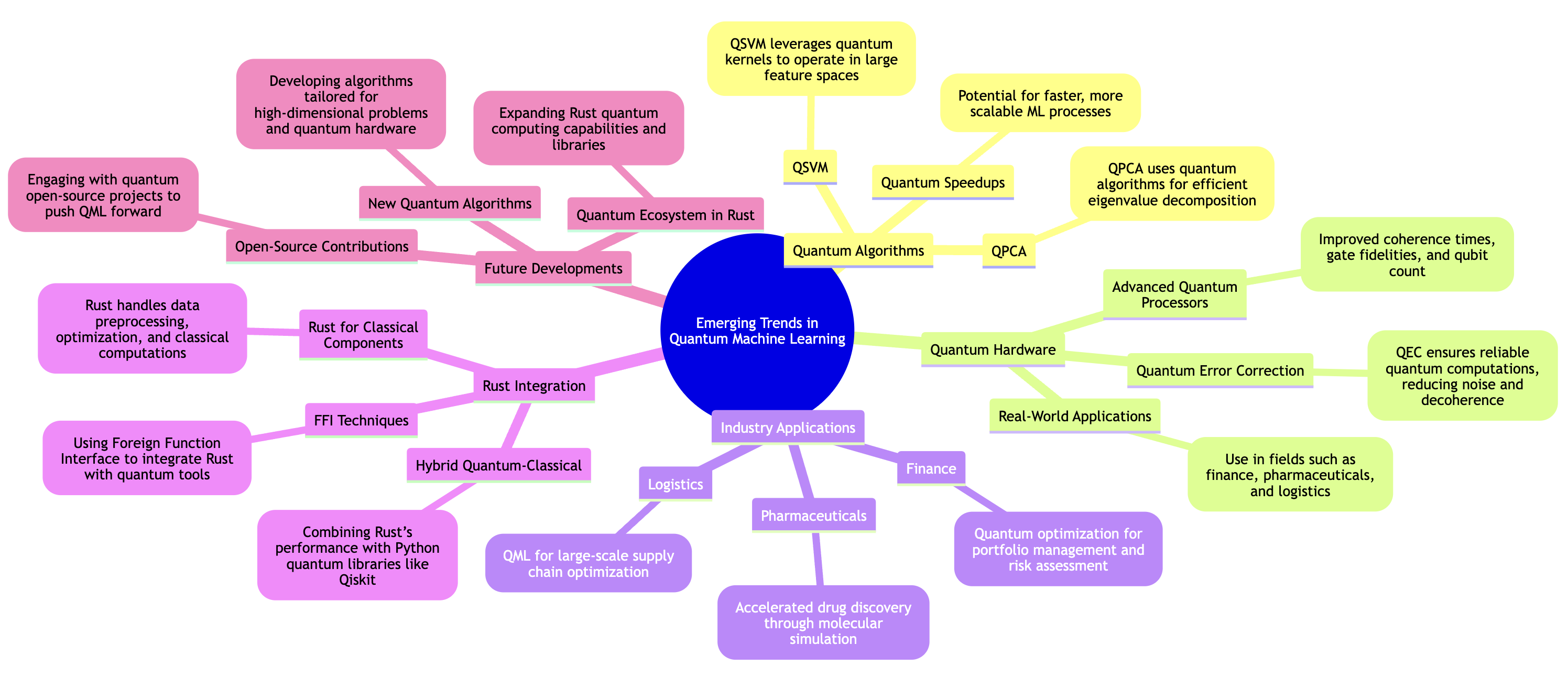

Chapter 26 of MLVR introduces readers to the fascinating and rapidly evolving field of Quantum Machine Learning (QML). The chapter begins by laying a solid foundation in quantum computing principles, such as qubits, superposition, and entanglement, which are crucial for understanding how quantum algorithms can outperform classical ones. It then delves into quantum algorithms specifically tailored for machine learning, highlighting their potential to revolutionize tasks like data encoding, pattern recognition, and optimization. The chapter explores the concept of quantum feature spaces, which allow models to operate in vastly expanded spaces, thus enabling more accurate and efficient learning. Hybrid quantum-classical models are also discussed, showcasing how the integration of quantum and classical components can tackle complex problems that are beyond the reach of classical computing alone. The chapter further introduces Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs), illustrating how they leverage quantum mechanics to process information in novel ways. Quantum optimization techniques, such as quantum annealing and QAOA, are presented as powerful tools for enhancing machine learning models. Throughout the chapter, practical guidance is provided on implementing these concepts using Rust, leveraging the growing ecosystem of quantum computing tools compatible with the language. The chapter also addresses the challenges and limitations of quantum machine learning, such as hardware constraints and error correction, while looking forward to the future of the field. By the end of this chapter, readers will have a comprehensive understanding of Quantum Machine Learning and be equipped with the skills to implement QML algorithms using Rust, positioning them at the forefront of this exciting domain.

26.1. Introduction to Quantum Computing

Quantum computing introduces a revolutionary approach to information processing by leveraging the principles of quantum mechanics, a domain that profoundly differs from the deterministic and binary nature of classical computation. At its core, quantum computing relies on qubits (quantum bits), which represent a fundamental shift from classical bits. While classical bits exist in one of two states (0 or 1), qubits can exist in a superposition of both states simultaneously, thanks to quantum mechanics. This property is what allows quantum computers to explore multiple possibilities at once, offering exponential potential for certain types of computations.

Figure 1: Google Quantum Computing machine.

Beyond superposition, entanglement plays a crucial role in quantum computing. Entanglement is a quantum phenomenon where qubits become interconnected in such a way that the state of one qubit is dependent on the state of another, no matter how far apart they are. This interconnectedness allows quantum computers to process information in ways that classical computers cannot, enabling faster data processing and more efficient problem-solving for certain complex tasks.

The next essential concept is quantum gates, which are the building blocks of quantum circuits. Just as classical computers use logic gates (AND, OR, NOT) to manipulate bits, quantum computers use quantum gates (like the Hadamard gate, Pauli-X gate, or CNOT gate) to manipulate qubits. However, quantum gates operate in a more complex manner, exploiting superposition and entanglement to perform operations on qubits that classical gates cannot.

Collectively, these concepts empower quantum computers to tackle problems that are computationally infeasible for classical machines. For example, quantum computers can exponentially speed up certain types of algorithms, such as Shor's algorithm for factoring large numbers (a task integral to breaking classical cryptographic schemes) and Grover's algorithm for searching unsorted databases.

Moreover, quantum computing can handle the simulation of quantum systems, something classical computers struggle with due to the exponential complexity of quantum states. This makes quantum computers particularly promising for applications in fields like quantum chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery, where understanding molecular interactions at the quantum level is vital.

At the heart of quantum computing is the qubit, the quantum analog of a classical bit. In classical computing, a bit can exist in one of two distinct states, 0 or 1. However, a qubit can exist in a superposition of both 0 and 1 simultaneously. Mathematically, the state of a qubit $\psi$ is described as a linear combination of the basis states ∣0⟩|0\\rangle∣0⟩ and ∣1⟩|1\\rangle∣1⟩:

$$ |\psi\rangle = \alpha |0\rangle + \beta |1\rangle $$

where $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are complex probability amplitudes that satisfy the normalization condition $|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1$. This superposition allows quantum computers to represent and process multiple states at once, exponentially expanding the computational space compared to classical bits. For a system with $n$ qubits, the number of possible states is $2^n$, enabling quantum systems to explore many computational paths simultaneously.

Entanglement is another fundamental property of quantum mechanics that quantum computing exploits. When qubits become entangled, the state of one qubit is intrinsically linked to the state of another, such that the measurement of one qubit instantaneously determines the state of the other, regardless of the distance separating them. For example, consider two qubits, $q_1$ and $q_2$, in an entangled state:

$$ |\psi\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(|00\rangle + |11\rangle) $$

In this maximally entangled state, if we measure $q_1$ and find it in state $|0\rangle$, we instantly know that $q_2$ must be in state $|0\rangle$ as well, and similarly for the state $|1\rangle$. This phenomenon, which defies classical intuition, is a key enabler of quantum computing’s parallelism and its ability to solve problems involving correlated systems more efficiently than classical computers.

Quantum gates are the quantum analogs of classical logic gates and serve to manipulate qubits. Unlike classical gates, which perform deterministic transformations on bits, quantum gates perform unitary operations on qubits, preserving quantum superpositions and entanglement. A basic example is the Hadamard gate $H$, which puts a qubit into an equal superposition of $|0\rangle$ and $|1\rangle$. Applying the Hadamard gate to a qubit initially in state $|0\rangle$ yields:

$$ H∣0⟩=12(∣0⟩+∣1⟩)H|0 $$

This operation demonstrates the quantum ability to explore multiple computational paths simultaneously. Quantum circuits are constructed by applying a series of such gates to qubits, manipulating them to perform more complex operations. Additionally, quantum gates like the controlled-NOT (CNOT) gate enable the creation of entanglement between qubits, further expanding the computational power of quantum systems.

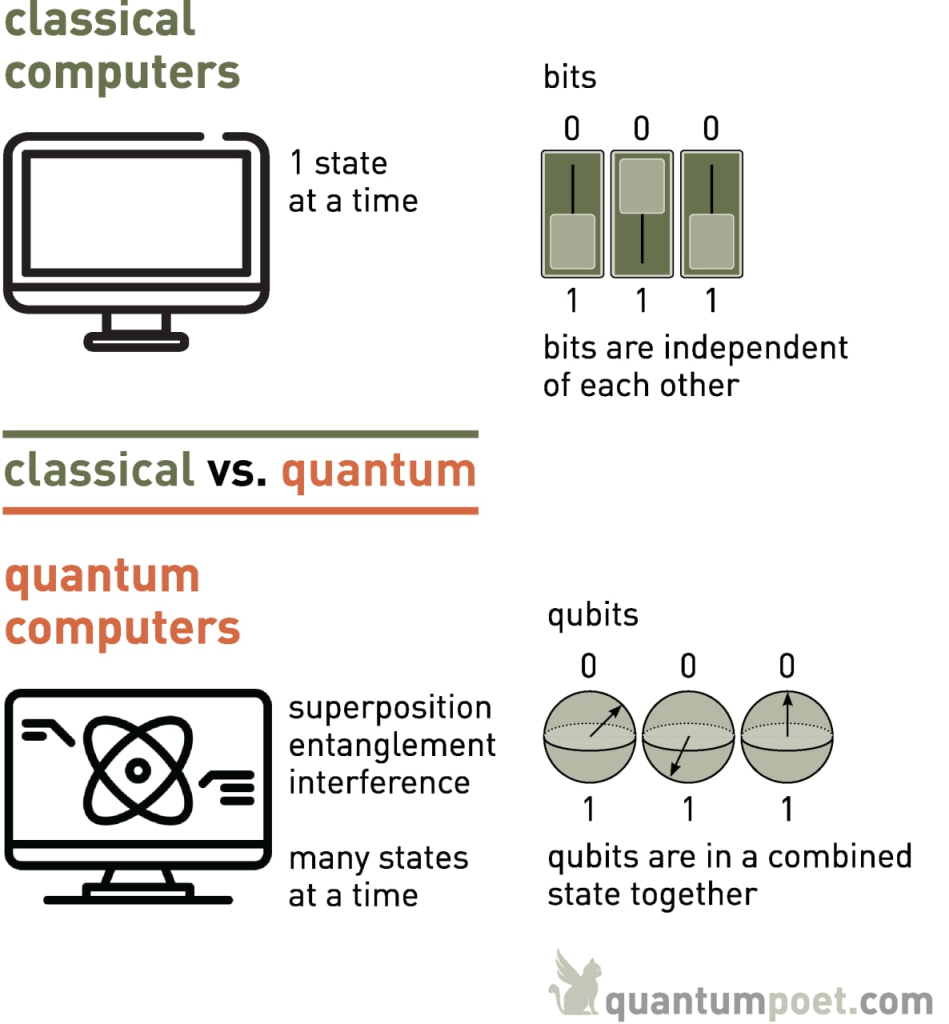

The key distinction between classical and quantum computing lies in the way information is processed. Classical computers are fundamentally deterministic, executing operations based on definite states of bits (either 0 or 1) and processing tasks sequentially or in parallel using classical parallelism. Classical parallelism allows multiple independent tasks to run simultaneously, but each task still processes one bit at a time. In contrast, quantum computers exploit quantum parallelism through superposition and entanglement, allowing them to perform multiple computations simultaneously on a much larger scale. The potential advantage of quantum computing is quantified by the notion of "quantum speedup," where certain classes of problems can be solved exponentially faster by quantum algorithms than by their classical counterparts.

Figure 2: Classical vs Quantum computer.

One notable example of quantum speedup is Shor’s algorithm, which addresses the problem of integer factorization—a task critical for cryptography. Classical algorithms for factoring large integers, such as those used in RSA encryption, operate with a time complexity that grows exponentially with the size of the input. For a number $N$, classical factorization algorithms have complexity $O(e^{(\log N)^{1/3}})$, making the problem infeasible for large values of $N$. Shor’s algorithm, by contrast, operates in polynomial time with respect to $\log N$, specifically $O((\log N)^3)$, achieving a dramatic quantum speedup. The power of Shor’s algorithm arises from quantum operations such as the quantum Fourier transform, which efficiently identifies the periodicity of functions that correspond to the factors of $N$.

Another area where quantum computing excels is in simulating quantum systems. Classical computers struggle with simulating quantum systems due to the exponential growth of the state space. A quantum system with nnn particles requires $2^n$ classical bits to fully represent its state, making simulation intractable for large systems. Quantum computers, by their nature, are well-suited to simulating quantum phenomena, as they can naturally encode quantum states and evolve them using quantum operations. This capability is crucial for fields such as chemistry and materials science, where understanding molecular interactions at the quantum level is essential.

The power of quantum computing lies in its ability to perform certain types of computations exponentially faster than classical computers by leveraging the principles of quantum mechanics. Problems involving combinatorial optimization, integer factorization, and quantum system simulation are among the tasks that benefit most from quantum algorithms. The ability to process vast amounts of information simultaneously through superposition and entanglement provides quantum computers with a computational edge that classical systems cannot match.

In summary, quantum computing represents a significant departure from classical computing, not only in its theoretical foundations but also in its practical capabilities. The core concepts of qubits, superposition, entanglement, and quantum gates provide the framework for quantum algorithms that outperform classical algorithms in specific domains. Quantum computers' ability to achieve quantum speedup in problems such as factorization and quantum simulations holds promise for advancing fields ranging from cryptography to quantum chemistry, heralding a new era in computational power and efficiency.

Rust, a system-level programming language known for its memory safety and performance, is an emerging choice for quantum computing development, though the ecosystem is still in its infancy compared to other languages such as Python. However, it’s possible to implement basic quantum circuits and operations in Rust by using foreign function interfaces (FFI) to integrate with established quantum computing libraries like IBM's Qiskit or other Python-based quantum frameworks.

To explore practical quantum circuits in Rust, let’s begin by constructing basic quantum gates using FFI to call Python's Qiskit library, as Rust does not yet have a fully developed quantum computing library like Qiskit. First, we need to set up a bridge between Rust and Python to make the necessary calls.

To install the required Rust dependencies for FFI with Python, include the pyo3 crate in the Cargo.toml file:

[dependencies]

pyo3 = { version = "0.22.2", features = ["extension-module"] }

Before running the code, you need to have the Qiskit and Qiskit Aer Python packages installed in your Python environment. Here’s how to install them from your terminal:

pip install qiskit qiskit-aer

Now, we can use the pyo3 crate to call Python functions from Qiskit in Rust. Below is an example of how to implement a quantum circuit in Rust that uses Python’s Qiskit library to create and manipulate a qubit:

use pyo3::prelude::*;

use pyo3::types::PyString;

fn main() -> PyResult<()> {

pyo3::prepare_freethreaded_python();

Python::with_gil(|py| {

// Import the Qiskit module

let qiskit = py.import_bound("qiskit")?;

// Import the Qiskit Aer module

let qiskit_aer = py.import_bound("qiskit_aer")?;

// Create a quantum circuit with one qubit

let quantum_circuit_cls = qiskit.getattr("QuantumCircuit")?;

let quantum_circuit = quantum_circuit_cls.call1((1,))?;

// Apply a Hadamard gate to put the qubit in superposition

quantum_circuit.call_method1("h", (0,))?;

// Measure the qubit

quantum_circuit.call_method0("measure_all")?;

// Initialize the simulator backend from qiskit_aer

let aer = qiskit_aer.getattr("Aer")?;

let get_backend = aer.getattr("get_backend")?;

let backend = get_backend.call1((PyString::new_bound(py, "qasm_simulator"),))?;

// Import transpile function from qiskit

let transpile = qiskit.getattr("transpile")?;

let transpiled_circuit = transpile.call1((quantum_circuit, &backend))?;

// Run the transpiled circuit on the backend

let run = backend.getattr("run")?;

let job = run.call1((transpiled_circuit,))?;

// Fetch the result

let result = job.call_method0("result")?;

let counts = result.call_method0("get_counts")?;

println!("Measurement results: {:?}", counts);

Ok(())

})

}

In this example, the Rust program constructs a basic quantum circuit with a single qubit, applies a Hadamard gate (which places the qubit in a superposition of states), and measures the result. This is achieved by calling Qiskit's functions via FFI. The pyo3 crate facilitates the communication between Rust and Python, allowing us to leverage the powerful quantum simulation capabilities of Qiskit while writing the logic in Rust.

Moving forward, as quantum computing continues to evolve, there is potential for native Rust libraries to emerge, which could integrate quantum operations directly into the Rust ecosystem without relying on FFI. For now, utilizing Python-based libraries like Qiskit offers a practical way to explore quantum algorithms and circuits within Rust, opening up the possibility for hybrid quantum-classical systems where Rust manages the classical components, and quantum operations are delegated to external platforms.

In the future, the combination of Rust’s system-level capabilities with the growing power of quantum computing could enable highly efficient quantum-classical hybrid applications, where Rust handles memory management, performance-critical code, and parallelization, while quantum computing provides the computational breakthroughs needed for tasks such as optimization, cryptography, and simulation of complex systems.

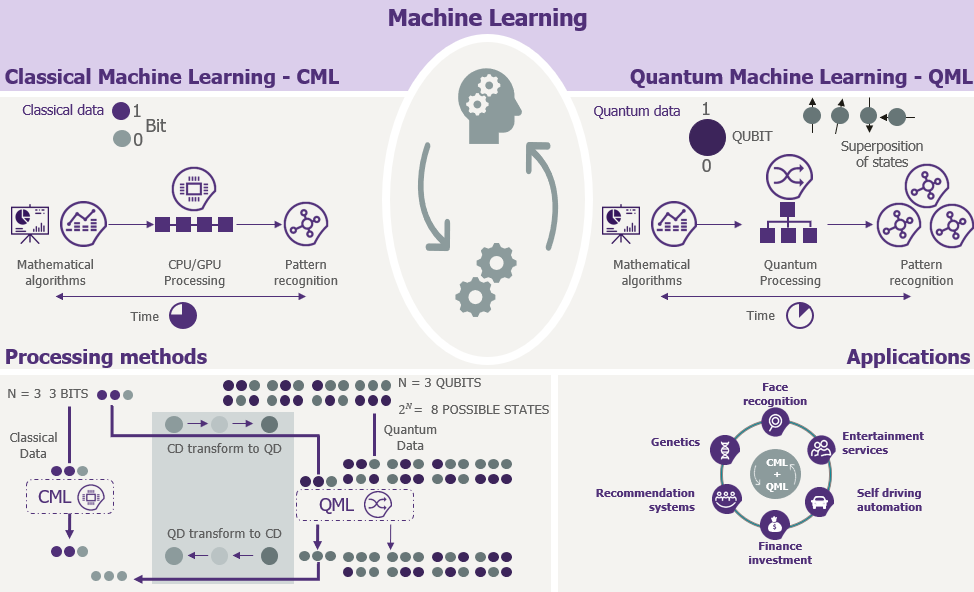

26.2. Quantum Algorithms for Machine Learning

Quantum machine learning (QML) represents an exciting frontier in the intersection of quantum computing and classical machine learning. By combining the principles of quantum mechanics with machine learning techniques, QML offers a new paradigm for accelerating computations, particularly for tasks that are computationally intensive for classical systems. Unlike classical computers, which process information in bits (0 or 1), quantum computers use qubits that can exist in a superposition of states, enabling them to process multiple possibilities simultaneously. This ability, along with entanglement—a phenomenon where qubits are interdependent regardless of distance—allows quantum computers to perform certain tasks exponentially faster than classical machines. These quantum properties make QML a promising field for transforming how we analyze and process large datasets.

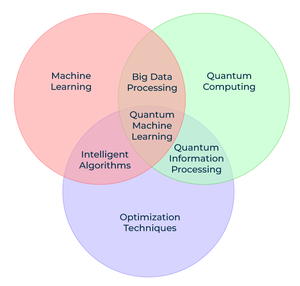

Figure 3: QML = ML + QC + Optimization.

A crucial aspect of QML is the ability to harness quantum parallelism, where quantum computers evaluate multiple inputs at once due to superposition. This feature is particularly useful in tasks involving optimization and search, which are central to many machine learning workflows. For example, in classical machine learning, algorithms must iteratively search through datasets or optimize functions, often requiring significant time and resources. Quantum algorithms, however, can explore vast solution spaces in parallel, offering potential speedups in these processes.

Several key quantum algorithms underpin the integration of quantum computing into machine learning. The Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT) is one such algorithm, serving as the quantum equivalent of the classical Fourier transform, widely used in data analysis and signal processing. In the context of machine learning, QFT can enhance tasks such as feature extraction and dimensionality reduction by processing complex transformations more efficiently than classical methods. Another fundamental algorithm is Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE), which is crucial for estimating eigenvalues in quantum systems. This algorithm has direct applications in machine learning models that rely on eigenvalue computations, such as principal component analysis (PCA) or linear discriminant analysis (LDA). Grover’s Search Algorithm is another powerful tool in QML, providing a quadratic speedup for searching unsorted data—a task that is common in many machine learning applications such as feature selection and hyperparameter optimization.

These algorithms provide the foundation for building quantum-enhanced machine learning models, which fall into two broad categories. The first is quantum-enhanced classical machine learning, where quantum algorithms are integrated into classical machine learning workflows to speed up specific tasks such as optimization, data sampling, or model training. The second category is fully quantum machine learning algorithms, where both data and operations are handled within the quantum computing framework. For instance, quantum support vector machines (SVMs) and quantum neural networks are emerging as quantum analogs to their classical counterparts, with the potential to outperform classical algorithms in scenarios involving large-scale optimization or high-dimensional data.

Figure 4: Processing methods and sample applications of QML.

However, despite the promise of quantum machine learning, significant challenges remain. Quantum hardware is still in its early stages, with current machines facing issues related to qubit decoherence, noise, and error rates. As a result, many QML models are developed for near-term quantum devices, which require careful consideration of noise tolerance and error correction. This has led to the rise of hybrid quantum-classical models, where classical computers perform most of the computation, and quantum devices are used for specific, computationally expensive subroutines.

Algorithm development is another area of rapid growth. While classical machine learning algorithms have been refined over decades, quantum machine learning algorithms are still in their infancy. Researchers are continually exploring new ways to leverage quantum properties to improve machine learning processes. Emerging quantum algorithms, such as variational quantum algorithms, quantum kernel methods, and quantum neural networks, are beginning to demonstrate potential in fields like optimization, reinforcement learning, and unsupervised learning.

The Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT) is the quantum analog of the classical discrete Fourier transform (DFT), and it serves as a building block for many quantum algorithms. The QFT transforms a quantum state $\psi\rangle$ from the computational basis into the Fourier basis. Formally, given a quantum state $|\psi\rangle = \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} x_k |k\rangle$, where $N = 2^n$ for an $n$-qubit system, the QFT maps this state into:

$$ \text{QFT}(|k\rangle) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{N}} \sum_{j=0}^{N-1} e^{2\pi i k j / N} |j\rangle $$

This transformation can be efficiently implemented on a quantum computer using a sequence of Hadamard gates and controlled phase shift gates. The QFT is pivotal in algorithms like Shor’s algorithm for factoring large integers and solving linear systems, making it an essential component for quantum machine learning tasks involving spectral analysis, pattern recognition, and data compression.

Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) is another critical quantum algorithm used to estimate the eigenvalues of unitary operators, which is central to many quantum applications, including solving eigenvalue problems and quantum chemistry simulations. In QPE, given a unitary operator $U$ and an eigenstate $|\psi\rangle$ with eigenvalue $e^{2\pi i \phi}$, the algorithm estimates $\phi$, where $\phi$ lies in the range $[0, 1)$. Mathematically, the phase estimation algorithm works by applying controlled applications of $U$ on an ancilla qubit register and performing the inverse QFT to extract the phase:

$$ |\psi_{\text{out}}\rangle = \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} e^{2\pi i \phi k} |k\rangle $$

The result of QPE provides a highly precise estimate of $\phi$, which is particularly useful in tasks such as finding the ground state energy of a quantum system or optimizing certain machine learning models that rely on spectral properties of matrices. For machine learning applications, QPE can be applied to problems that require the decomposition of large matrices, such as in kernel methods or principal component analysis (PCA), where the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a matrix are crucial.

Grover’s Search Algorithm provides a quadratic speedup for unstructured search problems, reducing the time complexity of finding a marked item in an unsorted database from $O(N)$ to $O(\sqrt{N})$, where $N$ is the size of the search space. The algorithm operates by applying Grover’s diffusion operator, which amplifies the probability of the marked state through a series of quantum iterations. Mathematically, the initial state is prepared as a superposition of all possible states:

$$ |\psi\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{N}} \sum_{x=0}^{N-1} $$

Grover’s operator then iteratively applies the oracle $O$, which marks the desired state, and the diffusion operator $D$, which inverts the amplitude of the state about the average. After approximately $O(\sqrt{N})$ iterations, the probability of measuring the marked state becomes maximized. Grover’s algorithm is particularly useful in quantum machine learning for tasks such as combinatorial optimization, database search, and feature selection, where finding a solution from a large search space can be computationally prohibitive for classical algorithms.

In quantum machine learning workflows, the integration of these quantum algorithms requires encoding classical data into quantum states. Classical data $x \in \mathbb{R}^d$ must first be mapped onto a quantum state $|\psi_x\rangle$. This can be achieved through various encoding schemes, such as amplitude encoding or basis encoding. For instance, in amplitude encoding, the data vector $x$ is normalized and encoded as the amplitude of a quantum state:

$$ |\psi_x\rangle = \frac{1}{\|x\|} \sum_{i=1}^d x_i |i\rangle $$

Once the data is encoded into quantum states, quantum algorithms such as the QFT, QPE, or Grover’s algorithm can be applied to process the data and compute solutions more efficiently than classical methods. For example, Grover’s algorithm can be used in machine learning for searching through a hypothesis space, while the QFT may be employed for tasks involving the spectral decomposition of matrices or solving systems of linear equations.

Quantum parallelism, which allows quantum computers to evaluate many possibilities simultaneously, offers significant potential speedups over classical machine learning methods. In a quantum superposition, a quantum computer can process multiple solutions at once, exploring a vast computational space in parallel. This enables certain machine learning tasks, such as optimization, clustering, and data classification, to be performed more efficiently on quantum hardware than would be possible using classical algorithms alone.

In practice, these quantum algorithms can be implemented using quantum computing libraries such as Qiskit (for Python) and Rust-based quantum libraries. Qiskit provides a rich set of tools for building quantum circuits and simulating quantum algorithms, while Rust’s performance and system-level control make it an ideal language for integrating quantum algorithms into larger machine learning workflows. Developers can leverage these libraries to implement quantum machine learning models that take advantage of the unique properties of quantum computation, potentially offering significant performance improvements for specific tasks.

In conclusion, quantum algorithms such as the Quantum Fourier Transform, Quantum Phase Estimation, and Grover’s Search Algorithm are key to advancing quantum machine learning by providing speedups in areas where classical algorithms struggle. These algorithms allow machine learning tasks involving spectral decomposition, optimization, and search to be performed more efficiently by harnessing quantum phenomena like superposition and entanglement. Implementing these algorithms in Rust and Python enables developers to integrate quantum computation into classical machine learning workflows, paving the way for new advancements in the field of quantum-enhanced machine learning.

Developing quantum-enhanced machine learning models requires specialized tools and libraries designed to interface with quantum computers. Qiskit, an open-source quantum computing framework developed by IBM, is widely used for building and simulating quantum circuits, offering comprehensive tools for implementing quantum algorithms, including those relevant to quantum machine learning (QML). Alongside its Python support, Qiskit is now being ported to Rust, taking advantage of Rust’s performance and safety features, which are ideal for high-performance quantum computing applications. Similarly, PyQuil, developed by Rigetti, facilitates the development of hybrid quantum-classical models, which are essential given the current limitations of quantum hardware, allowing smooth integration between classical and quantum workflows. In addition to these established Python-based tools, emerging Rust libraries like qrusty and Rust-QML are also being developed, offering Rust’s memory safety and efficiency for quantum computing. These Rust libraries are increasingly valuable for developers aiming to build reliable and high-performance quantum applications, particularly in the realm of machine learning.

To illustrate the practical implementation of these concepts, consider how to use quantum algorithms in Rust. Since Rust does not have dedicated quantum libraries, we utilize Python’s quantum computing libraries. The following example demonstrates how to implement Grover’s Search Algorithm using Rust and Python’s Qiskit library.

First, ensure you have the necessary Python dependencies installed. Use the following command in your terminal to install Qiskit:

pip install qiskit qiskit-algorithms

Next, include the pyo3 crate in your Rust project by adding it to your Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

pyo3 = { version = "0.22.2", features = ["extension-module"] }

Here’s an example of how to use Rust to call Python’s Qiskit library to implement Grover’s Search Algorithm:

use pyo3::prelude::*;

use pyo3::types::{PyDict, PyList};

fn main() -> PyResult<()> {

pyo3::prepare_freethreaded_python();

Python::with_gil(|py| {

// Import Qiskit modules

let qiskit_circuit_library = py.import_bound("qiskit.circuit")?;

let qiskit_algorithms = py.import_bound("qiskit_algorithms")?;

let qiskit_primitives = py.import_bound("qiskit.primitives")?;

// Define the oracle circuit for Grover's search

let oracle = qiskit_circuit_library

.getattr("QuantumCircuit")?

.call1((3,))?;

oracle.call_method1("ccz", (0, 1, 2))?;

// Define the state preparation circuit

let theta = 2.0 * (1.0 / (3.0_f64).sqrt()).acos();

let state_preparation = qiskit_circuit_library

.getattr("QuantumCircuit")?

.call1((3,))?;

state_preparation.call_method1("ry", (theta, 0))?;

state_preparation.call_method1("ch", (0, 1))?;

state_preparation.call_method1("x", (1,))?;

state_preparation.call_method1("h", (2,))?;

// Create the AmplificationProblem

let amplification_problem_cls = qiskit_algorithms.getattr("AmplificationProblem")?;

let amp_kwargs = PyDict::new_bound(py);

amp_kwargs.set_item("is_good_state", PyList::new_bound(py, &["110", "111"]))?;

amp_kwargs.set_item("state_preparation", state_preparation)?;

let problem = amplification_problem_cls.call((oracle,), Some(&_kwargs))?;

// Create the sampler

let sampler_cls = qiskit_primitives.getattr("Sampler")?;

let sampler = sampler_cls.call0()?;

// Create the Grover instance with keyword arguments

let grover_cls = qiskit_algorithms.getattr("Grover")?;

let grover_kwargs = PyDict::new_bound(py);

grover_kwargs.set_item("sampler", sampler)?;

let grover = grover_cls.call((), Some(&grover_kwargs))?;

// Run the Grover algorithm

let result = grover.call_method1("amplify", (problem,))?;

// Get and print the results

let top_measurement = result.getattr("top_measurement")?.extract::<String>()?;

let oracle_evaluation = result.getattr("oracle_evaluation")?.extract::<bool>()?;

println!("Success = {}", oracle_evaluation);

println!("Top measurement: {}", top_measurement);

Ok(())

})

}

In this example, the Rust program uses Python's Qiskit library to create a quantum circuit and apply Grover's Search Algorithm. The circuit is then executed, and the results are fetched and printed. This integration demonstrates how quantum algorithms can be incorporated into classical machine learning workflows and provides a foundation for comparing their performance with classical algorithms.

By combining the power of quantum algorithms with classical machine learning techniques, researchers and practitioners can explore new possibilities and achieve breakthroughs in areas such as optimization, data analysis, and pattern recognition.

26.3. Quantum Data and Feature Spaces

The use of quantum data and quantum feature spaces introduces a novel and powerful approach to representing and processing information by utilizing the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics. Classical data representation relies on bits, where information is encoded as discrete values—either 0 or 1. This binary system, though effective in classical computation, limits the amount of information that can be processed at a given time. Quantum computing, however, encodes information using qubits, which can exist not only in the states of 0 or 1 but also in any superposition of these states. This property of superposition allows a quantum computer to represent and process a significantly more complex and expansive set of data simultaneously.

Quantum feature spaces refer to the abstract, high-dimensional spaces where quantum data can be processed. By encoding classical data into quantum states, quantum machine learning models can transform the data into exponentially larger feature spaces, providing a richer and more nuanced representation of the information. In traditional machine learning, feature spaces represent the different dimensions or variables in which data points are described and classified. However, as the complexity of the problem increases, the dimensionality of the feature space required for effective processing also grows. Classical algorithms often struggle with this increase, especially when dealing with high-dimensional data due to the limitations of classical hardware and the curse of dimensionality.

Quantum computing offers a way to overcome these limitations by leveraging superposition and entanglement. Superposition enables a quantum system to encode multiple pieces of information within the same qubit. For instance, if a classical system uses three bits, it can represent one of eight possible states (2³ combinations). However, with three qubits, a quantum system can represent all eight states simultaneously, thanks to superposition. This allows quantum systems to explore exponentially larger feature spaces without the need to exponentially increase the number of qubits, offering a fundamentally different approach to data processing.

Moreover, entanglement plays a key role in enhancing the information-processing capability of quantum feature spaces. When qubits become entangled, the state of one qubit is intrinsically linked to the state of another, allowing quantum systems to process and manipulate interrelated data points in ways that classical systems cannot. This capability is particularly powerful when dealing with datasets that have complex relationships or dependencies between variables, as quantum systems can exploit these interdependencies more efficiently. In machine learning, this means that quantum algorithms can discover patterns and correlations within data that may be too subtle or complex for classical algorithms to detect.

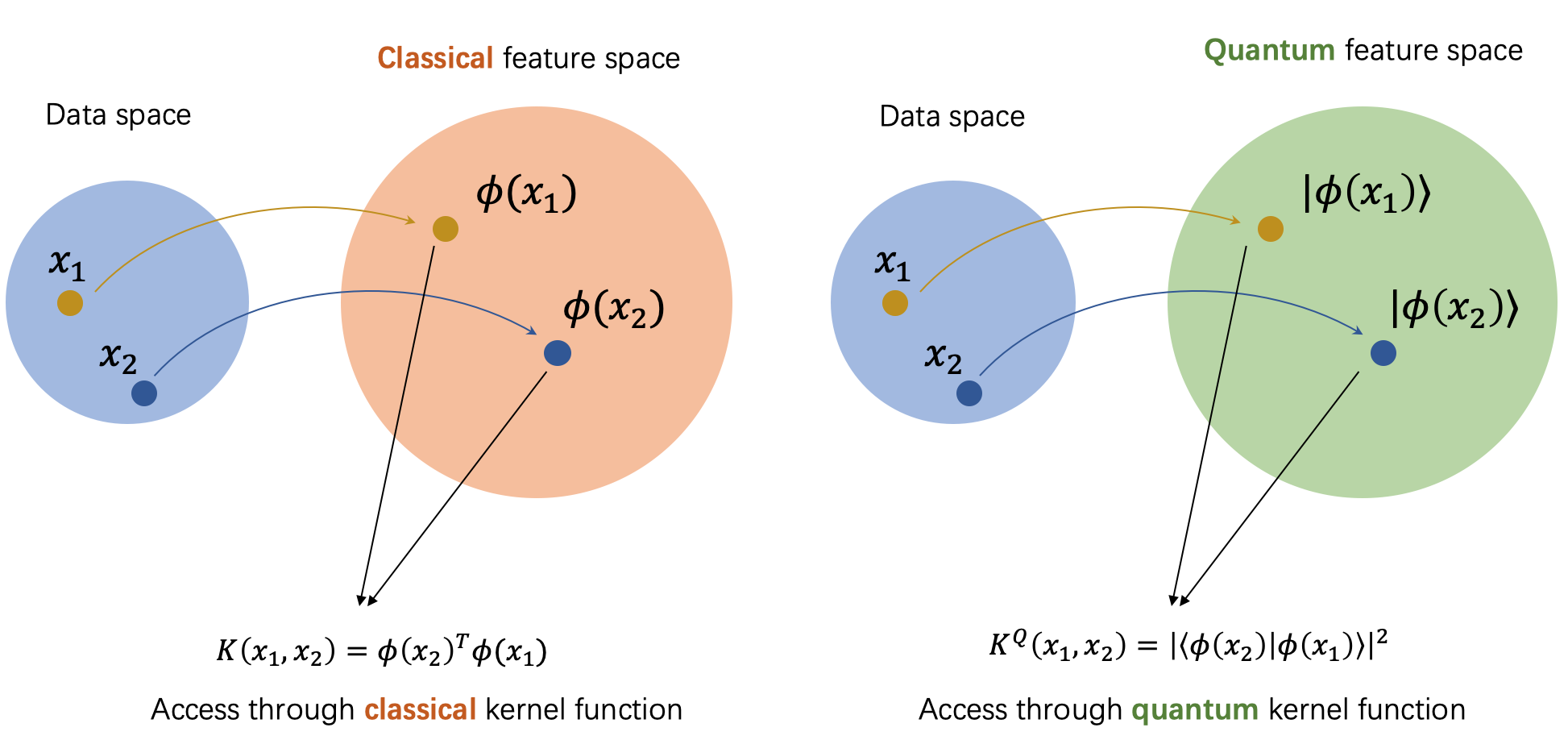

Figure 5: Classical vs Quantum data and feature spaces.

One of the key advantages of quantum feature spaces is that they allow for the development of quantum kernels, which are fundamental to many machine learning techniques, such as support vector machines (SVMs) and kernel methods. In classical machine learning, a kernel function transforms the data into a higher-dimensional space to make it easier to classify or analyze. Quantum kernels operate in a similar way but take advantage of the high-dimensional quantum feature spaces that quantum systems naturally provide. By leveraging quantum properties like superposition and entanglement, quantum kernels can represent data in much more intricate ways, allowing quantum machine learning models to distinguish between data points that would be indistinguishable in classical feature spaces. This leads to more powerful and efficient classification, clustering, and regression models.

The use of quantum data encoding is central to exploiting these quantum feature spaces. In many quantum machine learning algorithms, classical data is mapped to quantum states through a process known as quantum state preparation. This involves transforming classical inputs into a quantum state that can be manipulated by quantum algorithms. The encoding can be done in various ways, such as amplitude encoding, angle encoding, or basis encoding, depending on the type of data and the specific algorithm being used. By preparing classical data in quantum states, quantum machine learning models can take advantage of quantum operations that transform the data into feature spaces far beyond the reach of classical systems.

For instance, amplitude encoding is one method where classical data is mapped to the amplitudes of quantum states. This technique allows an exponentially large number of classical data points to be encoded into the amplitudes of just a few qubits, significantly reducing the memory required to store and process large datasets. Similarly, angle encoding maps classical data onto the angles of quantum gates, providing a different way to encode information into quantum circuits. Each of these encoding methods enables the construction of quantum feature spaces where complex operations, such as rotations, can be performed to manipulate data in high-dimensional spaces.

Ultimately, quantum data and feature spaces provide a pathway to more efficient and powerful machine learning models, especially for tasks involving large, high-dimensional datasets. By expanding the computational reach into these vast quantum feature spaces, quantum machine learning can offer a new level of problem-solving capability that is unattainable with classical models. As the field progresses, understanding how to effectively represent data in these quantum feature spaces will be crucial for developing quantum-enhanced machine learning algorithms that can unlock the full potential of quantum computing in areas such as optimization, pattern recognition, and data classification. The interplay between quantum data encoding, quantum kernels, and the manipulation of quantum feature spaces holds the promise of revolutionizing data processing and providing exponential speedups for certain machine learning tasks.

A qubit, the basic unit of quantum information, can be represented as a linear combination of its basis states $|0\rangle$ and $|1\rangle$, forming a superposition state. Formally, the state of a qubit can be expressed as:

$$|\psi\rangle = \alpha |0\rangle + \beta |1\rangle$$

where $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are complex coefficients known as probability amplitudes, and they satisfy the normalization condition $|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1$. The ability of a qubit to exist simultaneously in both the $|0\rangle$ and $|1\rangle$ states allows quantum systems to explore multiple computational paths in parallel, a property that classical systems lack. This parallelism extends to quantum machine learning by allowing quantum models to process complex and high-dimensional data representations more efficiently.

Quantum data refers to information encoded in quantum states rather than classical bits. Consider a classical dataset $D = \{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\}$, where each $x_i$ represents a data point in a $d$-dimensional space. In quantum machine learning, these data points are mapped to quantum states $|\psi(x_i)\rangle$ that reside in a quantum feature space. One method of encoding classical data into quantum states is amplitude encoding, where the data vector $x \in \mathbb{R}^d$ is normalized and its components are used as the amplitudes of a quantum state. The encoded quantum state is given by:

$$ |\psi_x\rangle = \frac{1}{\|x\|} \sum_{i=1}^d x_i |i\rangle $$

This encoding allows for the efficient representation of classical data in a quantum state, leveraging the high-dimensional nature of quantum feature spaces. In practice, these quantum states are manipulated using quantum gates, which can process data in ways that are not feasible using classical operations.

Quantum feature spaces extend this concept by enabling machine learning models to operate in exponentially larger spaces compared to classical models. In classical machine learning, the dimensionality of the feature space grows linearly with the number of input features. However, in quantum machine learning, the dimensionality of the feature space grows exponentially with the number of qubits used to encode the data. If a quantum system is represented by nnn qubits, the quantum feature space has a dimensionality of $2^n$, allowing quantum models to capture intricate patterns in the data more efficiently than classical models. For instance, a quantum machine learning model operating with nnn qubits can explore a feature space of dimension $2^n$, whereas a classical model with the same number of input features would only explore a linear space of dimension nnn.

This exponential growth of quantum feature spaces provides significant advantages for tasks such as pattern recognition, classification, and clustering, where the relationships between data points may be highly complex and difficult to capture using classical techniques. Quantum models can use quantum operations to transform data into these higher-dimensional spaces, where linear separation or pattern detection becomes more feasible. In the context of kernel methods, quantum machine learning leverages quantum feature spaces to efficiently compute inner products between quantum states, which are analogous to the kernel functions used in classical support vector machines (SVMs). The quantum kernel function between two data points $x$ and $x'$ is defined as the inner product of their corresponding quantum states:

$$ K(x, x') = \langle \psi(x) | \psi(x') \rangle $$

This quantum kernel can be computed efficiently on a quantum computer, providing a powerful tool for classifying data in high-dimensional quantum feature spaces. Quantum kernel methods are expected to outperform classical kernel methods in scenarios where the underlying data relationships are non-trivial and require exploration of complex feature transformations.

In terms of implementation, developing quantum machine learning models that leverage quantum data and feature spaces requires a solid understanding of quantum algorithms and tools. Rust, known for its performance and system-level control, provides an excellent platform for integrating quantum machine learning techniques. By using quantum libraries such as PyQuil (for Rigetti's quantum computers) or Qiskit (for IBM's quantum systems), developers can create hybrid workflows that integrate quantum and classical computing to solve machine learning problems. Rust’s concurrency model and memory safety guarantees allow for efficient management of quantum-classical workflows, ensuring smooth communication between classical data processing and quantum operations.

The practical applications of quantum data and feature spaces are vast, extending across multiple domains where machine learning plays a key role. In finance, quantum machine learning could improve the efficiency of portfolio optimization, risk management, and option pricing by exploring high-dimensional quantum feature spaces that capture intricate relationships between financial variables. In drug discovery and materials science, quantum feature spaces can be used to represent molecular structures, enabling quantum models to predict chemical properties more accurately than classical models.

In conclusion, the use of quantum data and feature spaces in quantum machine learning provides a powerful framework for representing and processing complex information. By leveraging quantum states and quantum parallelism, quantum models can explore exponentially larger feature spaces than classical models, offering potential speedups and improvements in tasks such as classification, clustering, and pattern recognition. Rust and its associated quantum computing libraries provide the necessary tools for implementing quantum machine learning models that take advantage of these quantum properties, opening the door to new advancements in data analysis and decision-making.

Practical implementation of quantum feature spaces involves encoding classical data into quantum states and using quantum feature maps to enhance model performance. In Rust, integrating quantum computing libraries such as pyo3 to interface with Python’s Qiskit allows for practical application of these quantum concepts. For example, consider the encoding of classical data into quantum states. We can use quantum circuits to prepare quantum states that encode classical data. This process typically involves applying quantum gates to initialize qubits into states that represent classical information.

Here is an illustrative example of encoding classical data into quantum states using Rust and Qiskit. Suppose we want to encode a classical vector into a quantum state. We can use the following Rust code to prepare a quantum circuit and apply an encoding gate:

use pyo3::prelude::*;

fn main() -> PyResult<()> {

pyo3::prepare_freethreaded_python();

Python::with_gil(|py| {

// Import Qiskit

let qiskit = PyModule::import_bound(py, "qiskit")?;

let quantum_circuit = qiskit.call_method1("QuantumCircuit", (2,))?;

// Example encoding of classical data

quantum_circuit.call_method1("h", (0,))?;

quantum_circuit.call_method1("cx", (0, 1))?;

println!("Quantum circuit with classical data encoding created.");

Ok(())

})

}

In this code, we initialize a quantum circuit with two qubits and apply Hadamard and CNOT gates to encode classical data into quantum states. The Hadamard gate creates a superposition, and the CNOT gate entangles the qubits, representing classical information in a quantum space.

To leverage quantum feature maps for enhancing model accuracy and efficiency, quantum circuits can be designed to transform quantum states into feature maps that are suitable for machine learning algorithms. For example, quantum feature maps can be used to create high-dimensional feature spaces where patterns in the data become more apparent. This is achieved by applying a series of quantum gates to prepare a feature map that represents data in a quantum-enhanced space.

Here is an example of how to use a quantum feature map in Rust:

use pyo3::prelude::*;

fn main() -> PyResult<()> {

pyo3::prepare_freethreaded_python();

Python::with_gil(|py| {

let qiskit = PyModule::import_bound(py, "qiskit")?;

let quantum_circuit = qiskit.call_method1("QuantumCircuit", (3,))?;

// Define feature map

quantum_circuit.call_method1("h", (0,))?;

quantum_circuit.call_method1("rzz", (1.0, 0, 1))?;

println!("Quantum circuit with feature map created.");

Ok(())

})

}

In this example, we prepare a quantum feature map by applying Hadamard and RZZ gates, which transform the quantum state into a feature map suitable for machine learning tasks. The RZZ gate introduces entanglement, which helps in representing complex relationships in the data.

By encoding classical data into quantum states and utilizing quantum feature maps, we can significantly enhance the accuracy and efficiency of machine learning models. This approach allows us to exploit the unique capabilities of quantum computing, such as superposition and entanglement, to achieve better performance in tasks like pattern recognition and data analysis.

In summary, quantum data and feature spaces provide a powerful framework for quantum machine learning, offering new possibilities for data representation and pattern recognition. Implementing these concepts in Rust through integration with Python’s quantum libraries enables practical exploration and application of quantum machine learning techniques, paving the way for advancements in various fields of research and technology.

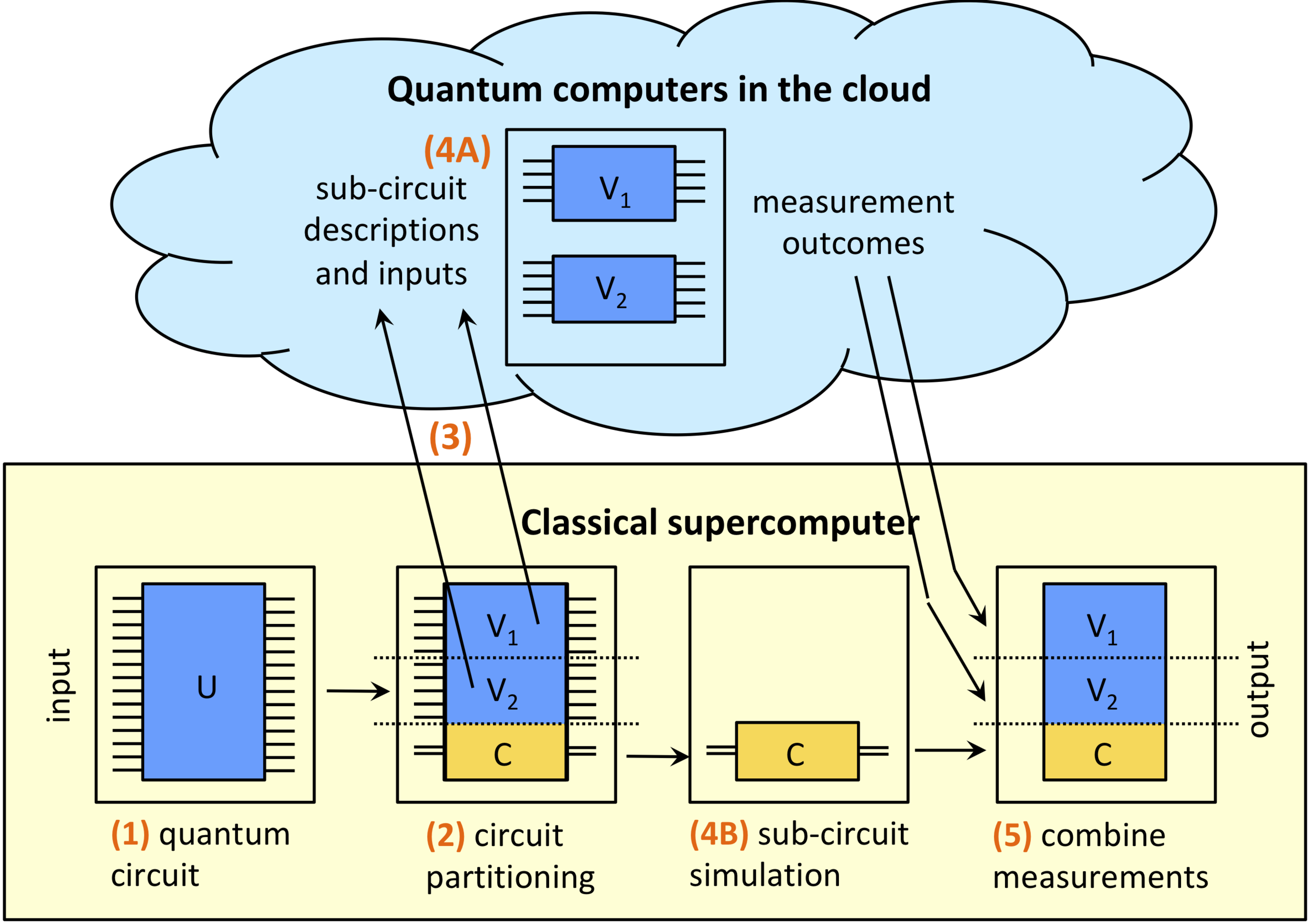

26.4. Hybrid Quantum-Classical Models

The field of quantum machine learning is evolving rapidly, with hybrid quantum-classical models emerging as one of the most promising approaches to leverage the advantages of both quantum and classical computing. These hybrid models integrate quantum computing, which excels in certain high-complexity tasks, with classical computing's well-established and robust algorithms, creating a powerful framework for solving problems that are intractable for either paradigm alone. In this section, we explore the theoretical foundations of hybrid quantum-classical models, how they merge the two types of computing, and their practical implementation using Rust, with interoperability through Python-based quantum libraries.

Figure 6: Hybrid classical + quantum computers.

At the core of hybrid quantum-classical models is the idea that quantum and classical resources can be used in tandem to solve specific subproblems of a larger computational task. Quantum computing offers a significant advantage in areas such as optimization, sampling, and feature transformation, where its ability to exploit superposition and entanglement allows it to process multiple possibilities simultaneously. However, quantum computers are still in their nascent stage, with limited qubit counts and error rates that pose challenges for larger tasks. Classical computing, by contrast, excels in tasks that involve high precision, large-scale data storage, and iterative processes such as training machine learning models. The goal of hybrid models is to maximize the strengths of both quantum and classical systems, using quantum computing where it provides a computational edge and classical computing where it offers robustness and scalability.

The mathematical structure of hybrid models is designed to split the workload between quantum and classical computations. Consider a typical optimization problem in machine learning, where the objective is to minimize a loss function $\mathcal{L}(\theta)$ with respect to the parameters $\theta$. In a hybrid quantum-classical setting, the loss function might be evaluated on a classical computer, while a quantum algorithm is used to explore the solution space and update the parameters. Mathematically, we can represent the hybrid process as:

$$ \theta^{(t+1)} = \theta^{(t)} - \eta \nabla_{\theta} \mathcal{L}_{\text{classical}}(\theta) + \lambda Q(\theta) $$

where $\eta$ is the learning rate, $\nabla_{\theta} \mathcal{L}_{\text{classical}}(\theta)$ is the gradient of the classical loss function, and $Q(\theta)$ represents the quantum contribution to the update, such as a quantum search or optimization algorithm. The parameter $\lambda$ adjusts the balance between classical and quantum updates. This formalization highlights how quantum and classical components work together within the optimization process.

In optimization problems, a common approach is to use quantum algorithms such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) or the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA), which are designed to solve specific quantum subproblems that appear in classical contexts. In VQE, for example, the quantum computer is used to find the ground state energy of a Hamiltonian $H$ by optimizing a variational quantum circuit. The objective function is the expected value of the Hamiltonian:

$$ E(\theta) = \langle \psi(\theta) | H | \psi(\theta) \rangle $$

where $|\psi(\theta)\rangle$ is a quantum state parameterized by classical variables $\theta$. The role of the quantum computer is to efficiently compute the expectation value of $H$, while the classical optimizer updates θ\\thetaθ iteratively. This hybrid approach allows quantum computers to perform the resource-intensive quantum operations while offloading the optimization to classical systems.

Another important application of hybrid quantum-classical models is in quantum kernel methods. In classical machine learning, kernel methods involve mapping data into a higher-dimensional feature space where linear separation of classes becomes possible. Quantum kernel methods exploit quantum feature spaces to perform this mapping exponentially faster than classical methods. Formally, given a classical dataset $D = \{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\}$, a quantum kernel function can be defined as:

$$ K(x, x') = \langle \psi(x) | \psi(x') \rangle $$

where $|\psi(x)\rangle$ is the quantum state encoding the data point $x$. The quantum computer computes this inner product in the quantum feature space, and the classical system uses this kernel matrix in standard machine learning algorithms like support vector machines (SVMs). Hybrid quantum-classical models thus extend classical machine learning techniques by leveraging quantum feature spaces for tasks such as classification, clustering, and regression, providing potential exponential speedups for certain problems.

From an implementation perspective, hybrid quantum-classical models can be constructed using Rust in combination with quantum computing libraries such as Qiskit or PyQuil, which are primarily Python-based. Rust’s strong performance and system-level control make it an ideal language for integrating quantum and classical computations, especially when working with complex, resource-intensive tasks. Through Rust’s interoperability with Python, libraries like PyO3 can be employed to connect Rust code with Python-based quantum libraries. In this hybrid setup, Rust can handle data preprocessing, classical optimization, and resource management, while Python-based quantum libraries manage the execution of quantum circuits and quantum algorithm implementations.

A typical workflow for a hybrid quantum-classical model might involve Rust performing classical machine learning tasks such as feature scaling, data partitioning, and gradient computation. Simultaneously, quantum components, written in Python using Qiskit or PyQuil, can execute the quantum circuits responsible for optimization or feature mapping. The results from the quantum computation are then passed back to the Rust system for further classical processing, forming a feedback loop between quantum and classical components. This type of hybrid workflow not only maximizes the computational advantages of both paradigms but also ensures efficient resource allocation, as Rust's concurrency model enables the parallel execution of tasks.

In conclusion, hybrid quantum-classical models represent an exciting frontier in machine learning, offering a pathway to solve complex problems by integrating the strengths of quantum and classical computing. By leveraging quantum algorithms for optimization, feature mapping, and kernel methods, while relying on classical systems for robust data handling and iterative processes, hybrid models aim to achieve superior performance for tasks that are challenging for classical systems alone. The practical implementation of these models, using Rust’s interoperability with Python-based quantum libraries, provides developers with a flexible and efficient framework for building cutting-edge quantum machine learning applications.

Here is an example demonstrating how to implement a hybrid quantum-classical model using Rust. In this scenario, we will use Rust to interface with Python’s quantum computing library, Qiskit, and a classical machine learning library. We will create a quantum component for feature transformation and use a classical component for model training.

First, ensure you have the necessary Python dependencies installed. Use the following command in your terminal to install Qiskit:

pip install qiskit qiskit-aer

Next, include the necessary crates in your Rust project by adding them to your Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

linfa = "0.7.0"

linfa-svm = "0.7.0"

ndarray = "0.15.0"

pyo3 = { version = "0.22.2", features = ["extension-module"] }

After that, we need to set up a quantum circuit for feature transformation using Qiskit. We will prepare a quantum state and apply quantum gates to transform the features:

use pyo3::prelude::*;

fn main() -> PyResult<()> {

Python::with_gil(|py| {

// Import Qiskit

let qiskit = PyModule::import(py, "qiskit")?;

let quantum_circuit = qiskit.call1("QuantumCircuit", (2,))?;

// Define feature transformation circuit

quantum_circuit.call_method1("h", (0,))?;

quantum_circuit.call_method1("cx", (0, 1))?;

println!("Quantum feature transformation circuit created.");

Ok(())

})

}

In this code, we create a quantum circuit with two qubits and apply Hadamard and CNOT gates to perform a feature transformation. This quantum feature map encodes classical data into quantum states, which can then be used for further processing.

Next, we integrate this quantum component with a classical machine learning model. For this example, we'll use a classical machine learning library, such as scikit-learn, to perform a classification task. We can combine the quantum feature transformation with a classical classifier in Python:

use pyo3::prelude::*;

use linfa::prelude::*;

use linfa_svm::Svm;

use linfa::Dataset;

use ndarray::Array2;

fn main() -> PyResult<()> {

pyo3::prepare_freethreaded_python();

Python::with_gil(|py| {

// Import necessary libraries

let qiskit = PyModule::import_bound(py, "qiskit")?;

let qiskit_aer = PyModule::import_bound(py, "qiskit_aer")?;

// Create a quantum feature transformation circuit

let quantum_circuit = qiskit.call_method1("QuantumCircuit", (2,))?;

quantum_circuit.call_method1("h", (0,))?;

quantum_circuit.call_method1("cx", (0, 1))?;

quantum_circuit.call_method1("save_unitary", ())?;

// Transpile the circuit for the simulator

let simulator = qiskit_aer.call_method0("AerSimulator")?;

let transpiled_circuit = qiskit.call_method1("transpile", (quantum_circuit, &simulator))?;

// Run the simulation

let result = simulator.call_method1("run", (&transpiled_circuit,))?.call_method1("result", ())?;

let unitary = result.call_method1("get_unitary", (transpiled_circuit,))?;

// Convert the unitary matrix to a real-valued format

let real_part = unitary.getattr("real")?.call_method0("tolist")?;

let imag_part = unitary.getattr("imag")?.call_method0("tolist")?;

// Flatten the real and imaginary parts and combine them into a single vector

let real_part_np: Vec<Vec<f64>> = real_part.extract()?;

let imag_part_np: Vec<Vec<f64>> = imag_part.extract()?;

let unitary_real_flat: Vec<f64> = real_part_np.into_iter().flatten().collect();

let unitary_imag_flat: Vec<f64> = imag_part_np.into_iter().flatten().collect();

let unitary_combined = unitary_real_flat.into_iter()

.chain(unitary_imag_flat.into_iter())

.collect::<Vec<f64>>();

// Example classical data

let labels: Vec<f64> = vec![0.0, 1.0, 1.0, 0.0];

// Create the DatasetBase object for training

let unitary_matrix = Array2::from_shape_vec((8, 4), unitary_combined.clone()).unwrap();

let labels_array = Array2::from_shape_vec((4, 1), labels).unwrap();

let dataset = Dataset::new(unitary_matrix.clone(), labels_array.column(0).to_owned());

// Train the SVM classifier

let svm = Svm::params()

.fit(&dataset)

.map_err(|e| PyErr::new::<pyo3::exceptions::PyRuntimeError, _>(format!("SVM error: {:?}", e)))?;

// Make predictions

let predictions = svm.predict(unitary_matrix);

println!("\nPredictions: {:?}", predictions);

Ok(())

})

}

In this code, we perform a quantum feature transformation and then use the transformed features with a classical Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier from linfa. The predictions are obtained by fitting the classifier with the transformed data and then making predictions.

This hybrid approach allows us to leverage quantum computing for feature transformation while using classical algorithms for model training and evaluation. The quantum component enhances the feature space, and the classical model utilizes these enhanced features to improve performance.

In summary, hybrid quantum-classical models offer a powerful way to combine the advantages of quantum and classical computing. By integrating quantum components for specific tasks with classical algorithms, we can achieve better performance and solve complex problems more effectively. Implementing these models in Rust with Python's quantum and classical libraries enables practical exploration of quantum machine learning techniques and paves the way for advancements in various applications.

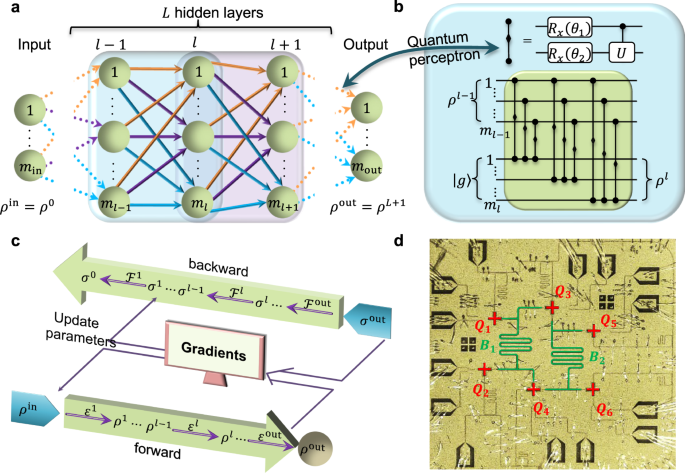

26.5. Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs)

Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) represent a promising and revolutionary framework that seeks to blend the principles of quantum mechanics with the structure of classical neural networks, aiming to create models that can tackle complex problems more efficiently. While classical neural networks rely on conventional computational techniques for tasks like learning, inference, and optimization, QNNs take advantage of the inherent properties of quantum mechanics, such as superposition and entanglement, to process information in fundamentally different ways. These quantum phenomena allow QNNs to explore much larger computational spaces simultaneously, potentially leading to faster convergence in training and improved performance on tasks that are computationally intractable for classical systems, such as simulating quantum systems, large-scale optimization, and high-dimensional data analysis.

At the heart of QNNs is the quantum perceptron, which is the quantum analog of the classical perceptron, a fundamental building block of neural networks. In a classical perceptron, input data is processed through weighted sums and passed through an activation function to produce an output. The quantum perceptron extends this concept into the quantum realm by encoding input data into quantum states and using quantum gates to manipulate these states in a manner analogous to the classical weighted sum. However, unlike classical perceptrons, quantum perceptrons can process superpositions of multiple inputs simultaneously, thanks to the property of quantum parallelism. This allows for the exploration of multiple potential outcomes in a single operation, offering a significant speedup for certain machine learning tasks.

The quantum backpropagation algorithm is another crucial component in the development of QNNs, building upon the classical backpropagation algorithm used in training neural networks. Classical backpropagation relies on the calculation of gradients of the error function with respect to the network’s weights, which are then adjusted to minimize the error and improve the network's performance. Quantum backpropagation extends this process by using quantum gates and quantum gradients, leveraging quantum information processing to achieve gradient descent in a potentially faster and more efficient way. Quantum algorithms, such as the Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) and Quantum Gradient Descent, can be used to compute these gradients more efficiently than classical methods, especially when dealing with large and complex networks.

Figure 7: Illustration of quantum neural network.

The advantage of using quantum backpropagation lies in its ability to handle quantum data and quantum states directly, which could be particularly useful in fields like quantum chemistry, materials science, and cryptography, where quantum systems are inherently difficult to model with classical techniques. By operating within the quantum domain, QNNs can potentially overcome the limitations of classical backpropagation, such as the vanishing gradient problem and slow convergence rates for deep networks. Additionally, quantum backpropagation could allow QNNs to train on data in high-dimensional quantum feature spaces more efficiently than classical algorithms, which often struggle with the curse of dimensionality.

An intriguing aspect of QNNs is their potential application to quantum-enhanced learning models, where quantum algorithms could be used to accelerate the learning process. For example, Grover’s search algorithm could be used within the quantum backpropagation framework to speed up the search for optimal network weights, leading to faster training times. Similarly, Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT) and Quantum Phase Estimation can be employed in the optimization process to identify eigenvalues and minimize error functions more efficiently.

The combination of quantum perceptrons and quantum backpropagation within QNNs opens up exciting possibilities for solving problems that are currently beyond the reach of classical neural networks. Tasks that involve large-scale optimization, combinatorial problems, and the simulation of quantum systems could particularly benefit from the quantum speedups offered by QNNs. In addition, QNNs may offer significant advantages in pattern recognition and data classification, particularly when applied to quantum datasets or high-dimensional classical data that is difficult for classical systems to process.

However, the development of QNNs is still in its early stages, and several challenges remain before they can fully realize their potential. One of the primary challenges is the noisy nature of current quantum hardware, which limits the depth and complexity of the quantum circuits that can be executed. Error correction techniques and fault-tolerant quantum computing will be crucial for scaling QNNs to more complex tasks. Additionally, designing efficient quantum algorithms for backpropagation and other machine learning tasks remains an open area of research, as existing quantum algorithms need to be refined and optimized for real-world applications.

Despite these challenges, the ongoing development of quantum neural networks offers a glimpse into a future where machine learning models could harness the full power of quantum computing. By integrating quantum perceptrons, quantum backpropagation, and other quantum algorithms into machine learning frameworks, QNNs could offer exponential speedups and novel approaches to tackling some of the most challenging problems in science, technology, and industry. As quantum computing hardware improves and quantum algorithms continue to evolve, QNNs may play a pivotal role in shaping the future of artificial intelligence and data-driven discovery.

In classical neural networks, information is passed through layers of neurons, each performing linear transformations followed by nonlinear activations. The weights between these layers are adjusted during training through optimization techniques such as gradient descent. In contrast, QNNs rely on quantum circuits, where qubits serve as the quantum analog of neurons, and quantum gates replace traditional linear transformations. A qubit can be in a superposition of states $|0\rangle$ and $|1\rangle$, represented mathematically as:

$$ |\psi\rangle = \alpha |0\rangle + \beta $$

where $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are complex coefficients such that $|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1$. This superposition allows a qubit to encode and process exponentially more information than a classical bit. For a system with $n$ qubits, the quantum state space grows exponentially to $2^n$, enabling QNNs to explore vast computational spaces and evaluate many possible outcomes in parallel.

Entanglement, another key property of quantum systems, plays a critical role in QNNs by allowing qubits to be correlated in such a way that the state of one qubit instantly influences the state of another, regardless of their physical distance. This quantum entanglement introduces an inherent parallelism and efficiency in computation that is unattainable in classical neural networks. Consider two entangled qubits $|\psi\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(|00\rangle + |11\rangle)$, where the measurement of the first qubit immediately determines the state of the second. This property is leveraged in QNNs to create more powerful models that can handle complex dependencies in data.

QNNs typically combine quantum circuits with neural network architectures, leading to hybrid models. These hybrid models consist of quantum circuits that act as layers in the neural network, where quantum gates apply transformations to the qubits, and quantum states encode information about the data. Quantum gates, such as the Hadamard gate or the controlled-NOT (CNOT) gate, serve as the building blocks of quantum circuits, analogous to the matrix multiplications and activation functions in classical networks. Formally, let $U(\theta)$ represent a parameterized quantum gate applied to a qubit $|\psi\rangle$, where $\theta$ represents the adjustable parameters (weights) of the QNN. The quantum circuit computes the evolution of the quantum state $|\psi(\theta)\rangle$ according to the applied gates:

$$ |\psi(\theta)\rangle = U(\theta) $$

where $|\psi_0\rangle$ is the initial state of the qubit system. The parameters $\theta$ are optimized during the training process in much the same way as the weights of a classical neural network are adjusted. However, in QNNs, this optimization is performed using variational quantum algorithms. These algorithms involve iteratively adjusting the quantum circuit parameters $\theta$ to minimize a loss function $\mathcal{L}(\theta)$, which measures the difference between the predicted and actual outputs of the network.

The training of a QNN is achieved through variational optimization, which is a process designed to iteratively optimize quantum parameters based on feedback from the network's output. The variational quantum circuit, parameterized by classical variables $\theta$, is adjusted by a classical optimizer that minimizes a loss function defined over the network’s outputs. The loss function might be defined similarly to classical machine learning models, for instance, using mean squared error (MSE) for regression tasks or cross-entropy loss for classification tasks. Mathematically, the goal is to find the set of parameters $\theta^*$ that minimize the loss:

$$ \theta^* = \arg \min_{\theta} \mathcal{L}(\theta) $$

where $\mathcal{L}(\theta)$ depends on the outputs of the quantum circuit, which are the probabilities of measuring certain quantum states after applying the quantum gates. A hybrid quantum-classical optimization routine is typically employed, where the quantum computer is used to evaluate the quantum circuit and compute the loss function, and a classical optimizer (such as gradient descent or a genetic algorithm) is used to adjust the parameters θ\\thetaθ.

A concrete example of a QNN application is in classification tasks, where quantum circuits can be used to process input data and make predictions. Classical data is first encoded into quantum states using techniques like amplitude encoding, which maps classical data vectors into quantum states. Once encoded, the quantum circuit processes the data, and measurements are made on the qubits to produce the final prediction. The entire process can be thought of as a hybrid system where the quantum circuit acts as a feature extractor, transforming the data into a high-dimensional quantum feature space, while the classical optimizer tunes the parameters to minimize the prediction error.

In conclusion, Quantum Neural Networks represent a frontier in machine learning, where quantum mechanical principles such as superposition and entanglement are harnessed within the architecture of neural networks. By integrating quantum circuits with classical optimization techniques, QNNs offer a new computational paradigm that could provide exponential speedups for certain machine learning tasks. These networks are particularly powerful for exploring complex, high-dimensional data and are implemented through hybrid models that combine the best of both quantum and classical computing. Through Rust and its interoperability with Python-based quantum computing libraries, developers have the tools to implement these cutting-edge models, paving the way for advancements in quantum machine learning.

In Rust, QNNs can be constructed using Python’s Qiskit Machine Learning library through PyO3. Below is an example of a Quantum Neural Network using Qiskit's EstimatorQNN. This model uses a parameterized quantum circuit and trains it with random inputs and weights to perform a forward and backward pass. The forward pass computes the network’s output, while the backward pass calculates the gradients for optimization.

Here is how your Cargo.toml should look:

[dependencies]

pyo3 = { version = "0.22.2", features = ["extension-module"] }

Additionally, the Python dependencies that need to be installed are:

pip install qiskit qiskit-algorithms qiskit-machine-learning

Here is the full code that integrates EstimatorQNN from Qiskit Machine Learning into a Rust environment:

use pyo3::prelude::*;

use pyo3::types::{PyDict, PyList, PyTuple};

fn main() -> PyResult<()> {

pyo3::prepare_freethreaded_python();

Python::with_gil(|py| {

// Import necessary Qiskit and Qiskit Machine Learning modules

let qiskit = PyModule::import_bound(py, "qiskit")?;

let qiskit_circuit = PyModule::import_bound(py, "qiskit.circuit")?;

let qiskit_nn = PyModule::import_bound(py, "qiskit_machine_learning.neural_networks")?;

let algorithm_globals = PyModule::import_bound(py, "qiskit_algorithms.utils.algorithm_globals")?;

let quantum_info = PyModule::import_bound(py, "qiskit.quantum_info")?;

// Construct the parametrized quantum circuit

let param_cls = qiskit_circuit.getattr("Parameter")?;

let input1 = param_cls.call1(("input1",))?;

let weight1 = param_cls.call1(("weight1",))?;

let qc_cls = qiskit.getattr("QuantumCircuit")?;

let qc1 = qc_cls.call1((1,))?;

qc1.call_method1("h", (0,))?;

qc1.call_method1("ry", (&input1, 0))?;

qc1.call_method1("rx", (&weight1, 0))?;

// Create the observable to define the expectation value computation

let sparse_pauliop = quantum_info.getattr("SparsePauliOp")?;

let observable1 = sparse_pauliop.call_method1("from_list", (PyList::new_bound(py, &[("Y", 1)]),))?;

// Instantiate the EstimatorQNN

let estimator_cls = qiskit_nn.getattr("EstimatorQNN")?;

let estimator_kwargs = PyDict::new_bound(py);

estimator_kwargs.set_item("circuit", qc1)?;

estimator_kwargs.set_item("observables", observable1)?;

estimator_kwargs.set_item("input_params", PyList::new_bound(py, &[input1]))?;

estimator_kwargs.set_item("weight_params", PyList::new_bound(py, &[weight1]))?;

let estimator_qnn = estimator_cls.call((), Some(&estimator_kwargs))?;

// Set-up random sets of input and weights

let num_inputs: usize = estimator_qnn.getattr("num_inputs")?.extract()?;

let num_weights: usize = estimator_qnn.getattr("num_weights")?.extract()?;

let estimator_qnn_input = algorithm_globals

.getattr("algorithm_globals")?

.getattr("random")?

.call_method1("random", (num_inputs,))?;

let estimator_qnn_weights = algorithm_globals

.getattr("algorithm_globals")?

.getattr("random")?

.call_method1("random", (num_weights,))?;

println!("Number of input features for EstimatorQNN: {}", num_inputs);

println!("Input: {:?}", estimator_qnn_input);

println!(

"Number of trainable weights for EstimatorQNN: {}",

num_weights

);

println!("Weights: {:?}", estimator_qnn_weights);

// Run forward pass

let forward_result = estimator_qnn.call_method1(

"forward",

(

PyTuple::new_bound(py, &[estimator_qnn_input.clone(), estimator_qnn_input.clone()]),

estimator_qnn_weights.clone(),

),

)?;

println!("Forward pass result for EstimatorQNN: {:?}.", forward_result);

// Run backward pass

let (input_grad, weight_grad): (PyObject, PyObject) = estimator_qnn

.call_method1("backward", (estimator_qnn_input, estimator_qnn_weights))?

.extract()?;

println!("Input gradients for EstimatorQNN: {:?}", input_grad);

println!("Weight gradients for EstimatorQNN: {:?}", weight_grad);

Ok(())

})

}

This code demonstrates the process of creating a QNN using Qiskit and running forward and backward passes for training the model. The quantum neural network is initialized by constructing a quantum circuit with parameterized quantum gates. The EstimatorQNN from Qiskit Machine Learning is used as the neural network model, with quantum observables defining the expectation value calculation.

The network is trained by generating random inputs and weights, running a forward pass to calculate the output of the network, and then using the backward pass to compute the gradients of the input and weight parameters. These gradients are used to update the quantum parameters during optimization, similar to how gradients are used to update weights in classical neural networks.

One of the key advantages of QNNs is their ability to leverage quantum superposition and entanglement to process information in a way that classical networks cannot. This opens up new possibilities for solving complex problems, particularly in the realm of optimization, pattern recognition, and quantum machine learning.

The example provided is a fundamental starting point for understanding how QNNs work. As quantum computing technology continues to advance, QNNs will likely become an essential tool in solving problems that are intractable for classical neural networks.

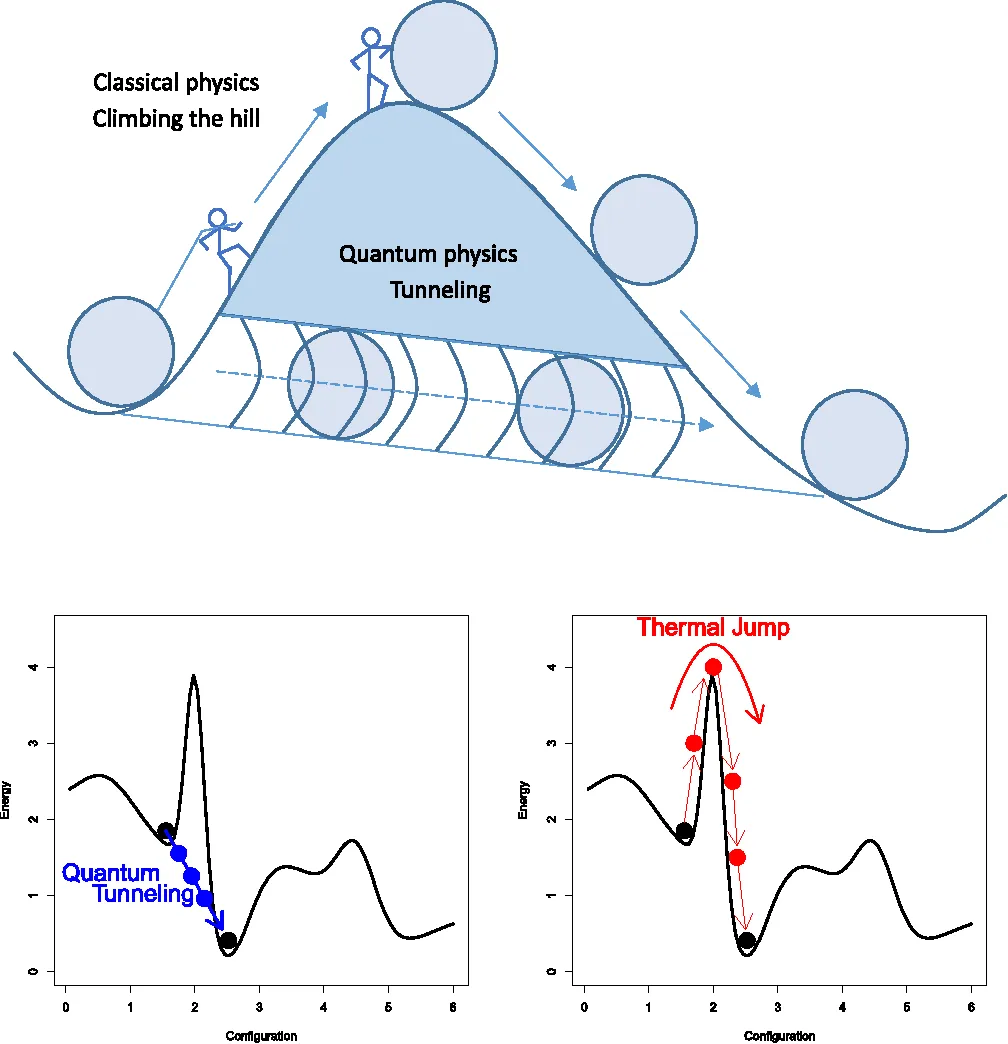

26.6. Quantum Optimization for Machine Learning

Quantum optimization is a powerful approach that leverages the principles of quantum mechanics to address complex optimization problems that are computationally challenging for classical algorithms. In machine learning, optimization is at the heart of many tasks, including model training, parameter tuning, and solving combinatorial problems. Quantum optimization techniques such as quantum annealing and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) offer potential advantages by allowing quantum systems to explore vast solution spaces more efficiently. This section delves into the mathematical, conceptual, and practical aspects of quantum optimization, with a focus on how these techniques can be implemented in Rust, interfacing with quantum computing libraries through Python.

At the core of quantum optimization is the ability of quantum systems to leverage superposition and entanglement to explore multiple solutions simultaneously. This quantum parallelism allows quantum algorithms to process a larger portion of the solution space in a single computation, offering the potential for faster convergence to optimal or near-optimal solutions compared to classical methods.

Figure 8: Advantage of quantum annealing algorithm (Project Euclid).

Quantum annealing is an optimization technique that exploits quantum tunneling to find the global minimum of a problem’s energy landscape. Formally, an optimization problem can be framed as minimizing an objective function $f(x)$, where $x \in \mathbb{R}^d$ represents a high-dimensional input vector. In the context of quantum annealing, the objective function is mapped onto the energy of a quantum system described by a Hamiltonian $H$. The goal of quantum annealing is to find the state $|x\rangle$ that minimizes the expectation value $\langle x | H | x \rangle$, which corresponds to the lowest energy configuration of the system. Mathematically, quantum annealing involves evolving the quantum system from an initial Hamiltonian $H_{\text{initial}}$ to a final Hamiltonian $H_{\text{final}}$ that encodes the problem’s objective function:

$$ H(s) = (1 - s) H_{\text{initial}} + s H_{\text{final}} $$

where $s \in [0, 1]$ is a time-dependent parameter. As $s$ evolves from 0 to 1, the system transitions from an easily solvable ground state of $H_{\text{initial}}$ to the ground state of $H_{\text{final}}$, which corresponds to the solution of the optimization problem. The quantum tunneling effect allows the system to escape local minima that might trap classical optimization methods, potentially leading to a more efficient search for the global minimum.

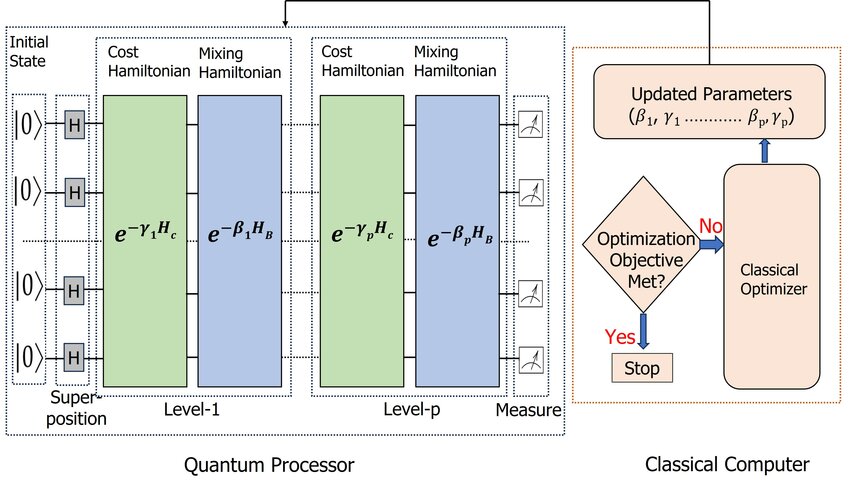

Figure 9: Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA).